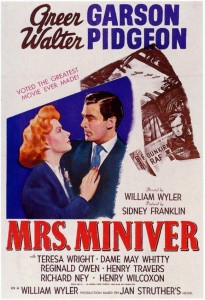

Mrs. Miniver is more than a picture— It’s dramatic. It’s tender. It’s human. It’s real.

The British class system that had begun to disintegrate even before its almost—almost—complete dissolution (it still persists) with World War I, and which was so horribly exposed in the discriminatory survival rates in the sinking of the “Titanic,” is a strong sub-plot in William Wyler’s 1942 Mrs. Miniver. In an early part of the film, a new student at Oxford and son of the stalwart mother of the title, is rude to a visiting young lady, denouncing her as an example of the landed gentry exercising medieval rights over the middle-class, though affluent Minivers.

The English world of Mrs. Kay Miniver, with its rose competition and garden parties, its jovial camaraderie and blissful innocence, never existed, at least not as idealized in the film. Rather, it is M-G-M’s—that is, an American—version of what the English people and their village life must be like, rose-colored, sweet and sentimental. The film was a morale-booster from the sincere Americans who were then only six-month veterans of World War II, while Britain had been at war for over two and a half years. Weapons and food, though, had been cargoed for more than a year to the beleaguered island nation under Lend-Lease.

The reason for Carol’s visit is to ask Mrs. Miniver to persuade a flower show competitor—another of the so-called “vassals”—to withdraw his rose, as her grandmother is used to winning. “I’m aware of the influence of the feudal system in this village,” the son tells Carol. “These are orders from the manor. Her ladyship must be offered no competition.”

And so the film begins, establishing a warm-hearted, generally frivolous atmosphere. After all, what could be more frivolous in the face of war than who might win a flower show or worries about class distinction, an inequality though it may be? Or what about Mrs. Miniver (Greer Garson)? In the very opening of the movie, she is indecisive, practically distraught, over whether or not to buy a hat. Already apprehensive about her initial decision, she boards a London bus, then immediately gets off to return to the hat shop and, there, relieved—oh, how relieved, her heart pounding, her eyes anxious!—to find that that particular hat hasn’t been sold.

And so the film begins, establishing a warm-hearted, generally frivolous atmosphere. After all, what could be more frivolous in the face of war than who might win a flower show or worries about class distinction, an inequality though it may be? Or what about Mrs. Miniver (Greer Garson)? In the very opening of the movie, she is indecisive, practically distraught, over whether or not to buy a hat. Already apprehensive about her initial decision, she boards a London bus, then immediately gets off to return to the hat shop and, there, relieved—oh, how relieved, her heart pounding, her eyes anxious!—to find that that particular hat hasn’t been sold.

On the way home, Mrs. Miniver is approached by the stationmaster, James Ballard (Henry Travers, the memorable angel in the 1946 It’s a Wonderful Life). He shows her his treasured rose entry for the upcoming annual flower show. He wants her permission to name it “The Mrs. Miniver.” She is flattered. “I think it’s lovely having flowers named after you.”

Once home, she enters the house, bypassing a sports car in the street, in which her husband, Clem (Walter Pidgeon) has slunk down in the front seat so she won’t see him. He, too, is hesitating about a purchase. Unable to persuade the car salesman to lower his price, he says he’ll take it. That night at dinner, while Kay is anxious about how to reveal her “extravagant” hat purchase, Clem hints they need a new car, beginning by mentioning a recent puncture. “I think,” she suggests, “you ought to buy yourself a new tyre one of these days.” Not exactly the direction he wanted the conversation to go!

Once home, she enters the house, bypassing a sports car in the street, in which her husband, Clem (Walter Pidgeon) has slunk down in the front seat so she won’t see him. He, too, is hesitating about a purchase. Unable to persuade the car salesman to lower his price, he says he’ll take it. That night at dinner, while Kay is anxious about how to reveal her “extravagant” hat purchase, Clem hints they need a new car, beginning by mentioning a recent puncture. “I think,” she suggests, “you ought to buy yourself a new tyre one of these days.” Not exactly the direction he wanted the conversation to go!

How better, then, to set up a situation before knocking it down?

A mood now established, it changes, first when the vicar (Henry Wilcoxon, looking and sounding a bit like a later-aged Laurence Olivier) announces Prime Minister Chamberlain’s declaration of war, and the service ends with the hymn “O God, Our Help in Ages Past.”

Vin (Richard Ney), who had sounded so mature with his egalitarian speeches but is really an unsophisticated youth, apologizes to Carol (Teresa Wright), granddaughter of Lady Beldon (Dame May Whitty), the cause of his animosity. Following a short courtship, Vin and Carol fall in love and marry. After a neighbor, Horace (Rhys Williams, who had made his film début the year before in How Green Was My Valley), joins the Army, Vin joins the Royal Air Force. Clem volunteers his motorboat—the Minivers have a dock on the Thames—to help evacuate the defeated British and French armies from Dunkirk.

While Clem is away, there is an air raid and a German plane crashes nearby. The injured pilot (Helmut Dantine, resident Nazi villain, including three Errol Flynn films) holds Kay at gunpoint until he collapses. Then she takes his gun, feeds him and they have a political argument. “Soon we will finish it,” he says. “Others come—like me. Thousands. Many thousands. Better. . . . You will see. We will come. We will bomb your cities—like Barcelona, Warsaw, Narwik, Rotterdam. Rotterdam we destroyed in two hours.”

While Clem is away, there is an air raid and a German plane crashes nearby. The injured pilot (Helmut Dantine, resident Nazi villain, including three Errol Flynn films) holds Kay at gunpoint until he collapses. Then she takes his gun, feeds him and they have a political argument. “Soon we will finish it,” he says. “Others come—like me. Thousands. Many thousands. Better. . . . You will see. We will come. We will bomb your cities—like Barcelona, Warsaw, Narwik, Rotterdam. Rotterdam we destroyed in two hours.”

In one of the film’s best scenes, Lady Beldon pleads with Kay to discourage her son from marrying her granddaughter. Kay is very persuasive, asserting that time is so important in wartime, that they are not too young, that her ladyship herself had married at sixteen, that Vin is, after all, “a nice boy.” The scene is notable for the long takes from Joseph Ruttenberg’s always deft camera and the natural, glowing appeal of Garson. In a later scene, when Kay suggests that other people deserve to win flower trophies, Lady Beldon says to her, “You have such a way of looking at people.”

In another air raid, the Minivers and their two younger children (Clare Sandars and Christopher Severn) take refuge in the backyard bomb shelter, one quite more spacious than the government-issued Anderson and Morrison shelters, and the kids fall asleep to Kay’s reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Clem points out an air vent and warns of gas. “If you see this gauze change color, grab this [cover] and shut it with a bang like this, you see?” “Then what happens?” Kay asks. “We suffocate,” he replies.

The garden party, with its glee club singing, concert band and flower awards, is, in some ways, the climax of the film. Lady Beldon’s roses have been taking first place since the contest began, through tradition and citizenry fear of her. She receives a note from the judges. Once again she has won first place for the best rose, but after Kay’s influence and all that has gone before, she announces a different winner . . . Mr. Ballard.

The garden party, with its glee club singing, concert band and flower awards, is, in some ways, the climax of the film. Lady Beldon’s roses have been taking first place since the contest began, through tradition and citizenry fear of her. She receives a note from the judges. Once again she has won first place for the best rose, but after Kay’s influence and all that has gone before, she announces a different winner . . . Mr. Ballard.

On their return home after driving Vin to join his squadron, Kay and Carol’s car is strafed by a German fighter and young Carol is killed.

In the film’s final scene, the two bereaved families attend church. The vicar delivers a long, morale-building sermon that would slow down today’s fast-paced films—in fact, wouldn’t be allowed. Lady Beldon is alone in her private box pew until Vin joins her in singing “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” one of the hymns Winston Churchill chose to be sung aboard the battleship “Prince of Wales” when he and Franklin D. Roosevelt secretly met off Newfoundland in August 1941 to draw up the Atlantic Charter.

Viewed through a hole in the church roof, a flight of British fighters, probably Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes, head for the enemy and the defense of the nation. This is accompanied by the second theme—the famous “graduation” procession—of Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1, segueing into the end cast. All that is needed would be the voice of Winston Churchill, which was actually overlaid in a London Phase-4 soundtrack LP of Mrs. Miniver in 1975, though omitted in the CD reissue, perhaps finally deemed a little too much.

Viewed through a hole in the church roof, a flight of British fighters, probably Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes, head for the enemy and the defense of the nation. This is accompanied by the second theme—the famous “graduation” procession—of Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1, segueing into the end cast. All that is needed would be the voice of Winston Churchill, which was actually overlaid in a London Phase-4 soundtrack LP of Mrs. Miniver in 1975, though omitted in the CD reissue, perhaps finally deemed a little too much.

While the British might have laughed at their cousins across the Atlantic for their idea of English life, Mrs. Miniver is far from a dud, then or in retrospect, whatever the criterion today. To some extent dated, mainly because the sentiment of caring for one’s neighbor now seems foreign to so many people, the film is beautifully scripted, acted and photographed. Its musical score, however, is more dependent upon the source material—hymns and traditional and patriotic songs—than anything second-stringer Herbert Stothart comes up with, however sentimental, especially for those scenes involving Henry Travers.

The film won six Oscars—for Picture, Director (Wyler), Actress (Garson), Supporting Actress (Wright), Adapted Screenplay (James Hilton and three others) and Cinematography (Ruttenberg).

Because over 27,000 members of the movie industry were in the service in 1942, the studios were having to borrow supporting players from each other. From Universal, 20th Century-Fox, Warner Bros., Paramount and other studios, as well as from M-G-M, a huge cast of familiar faces appears in Mrs. Miniver. The great majority are British-born, many with non-speaking roles: bell-ringer Forrester Harvey, Mary Field (Eve in How Green Was My Valley), Ian Wolfe (surely in the running for the most films made by anybody), Alec Craig, housemaid Brenda Forbes (sister of Ralph Forbes and daughter of Mary Forbes, who was Mrs. Kirby in You Can’t Take It with You), Vernon Steele, air raid warden Reginald Owen (both Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson in two films in the early ’30s), Miles Mander, John Burton, David Clyde, Colin Campbell and a plethora of others.

No doubt about it: Greer Garson, the woman who rescues Ronald Colman from a mental institution in Random Harvest, helps husband discover radium in Madame Curie, rehabilitates a stuffy British don in Goodbye, Mr. Chips (her début) and, in a lesser movie, brings medicine and refinement in Strange Lady in Town, makes Mrs. Miniver what it is. She is something of a presence on screen and—again, no doubt about it—the camera likes her, in the sense it likes Marilyn Monroe. Not in the same way. Garson is always a lady, and would be ludicrous as anything else, even in a bathing suit.

No doubt about it: Greer Garson, the woman who rescues Ronald Colman from a mental institution in Random Harvest, helps husband discover radium in Madame Curie, rehabilitates a stuffy British don in Goodbye, Mr. Chips (her début) and, in a lesser movie, brings medicine and refinement in Strange Lady in Town, makes Mrs. Miniver what it is. She is something of a presence on screen and—again, no doubt about it—the camera likes her, in the sense it likes Marilyn Monroe. Not in the same way. Garson is always a lady, and would be ludicrous as anything else, even in a bathing suit.

And Teresa Wright. One of my favorite actresses, she always conveys a girlish and virginal demeanor, as she does here, even at twenty-four in 1942. Like Garson, she had a string of wonderful, quality pictures in the beginning of her career, in Wright’s case during a six-year period from 1941: The Little Foxes, Mrs. Miniver, The Pride of the Yankees, Shadow of a Doubt and The Best Years of Our Lives. And also like Garson, she went into television in the mid-’50s. In 1997, Wright emerged for the theatrical The Rainmaker, her last screen appearance.

And Teresa Wright. One of my favorite actresses, she always conveys a girlish and virginal demeanor, as she does here, even at twenty-four in 1942. Like Garson, she had a string of wonderful, quality pictures in the beginning of her career, in Wright’s case during a six-year period from 1941: The Little Foxes, Mrs. Miniver, The Pride of the Yankees, Shadow of a Doubt and The Best Years of Our Lives. And also like Garson, she went into television in the mid-’50s. In 1997, Wright emerged for the theatrical The Rainmaker, her last screen appearance.

In 1950 Henry Wilcoxon would reprise his role as the vicar in The Miniver Story, a sad demise both for the screen character and as a film sequel. Pidgeon and Garson, who made eight other films together, were reunited for Kay’s death, protracted and sentimentalized in the worst of soap opera self-indulgence. M-G-M erred in this endeavor. Better to have allowed Kay to linger forever in memory: that resolute and wise defender of home and family at a time of one nation’s greatest trial.

That failed movie was not directed by William Wyler. Rather H. C. Potter is due the blame. Wyler, having directed a multi-Oscar winner at the beginning of the war in Mrs. Miniver, would, at the end of the war, direct The Best Years of Our Lives, winning more Oscars still.

Great review! I love this movie and have to watch it at least once per year.

I was twelve years old when I saw this movie, and immediately fell in love with Helmut Dantine, the German soldier who is wounded and comes into Mrs. Miniver’s home. I saw the movie several times, just so I could see him. Then in 1946 he came to Cleveland ohio in a play called The Eagle Has Two Heads, with Talulah Bankhead. After the play my friend and I went into the backstage area, met ms. Bankhead and got her autograph. She asked if we would like to meet mr Dantine, and took us to his dressing room. I still have both of their autographs in my autograph book. Also their pictures from the program.

Thanks for the interesting review, especially the analysis the theme of class running through the film. When I first heard about Mrs. Miniver, I could understand why everyone was praising a war movie where a rose competition was the climax. Until I watched it. Charming does not begin to describe the movie. I have seen it several times since and it has impressed me more each time.

A very affecting movie with a mostly great cast. I’m just curious, though, why Mrs. Miniver would drive home, shlep the mortally wounded Carol out of the car and into the house, dump her on the floor, and then call an ambulance, instead of just driving her to the hospital? or leaving her stretched out on the front seat while running in to make the call? Did that scene make sense to people in 1941?

I just wish someone would colorize just the roses in the movie. That would be an awesome touch…💯