“Tell me corporal. Which is more important, a corporal or a general?” — General Tanz

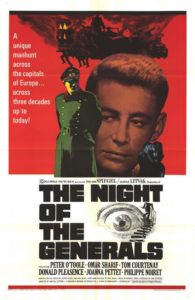

Despite being less than a top-notch film, The Night of the Generals is one of my guilty pleasures. I wallow in the enjoyment of it when, true, I could be watching a better movie.

The 1967 film borders on mediocrity, close to a cinematic blunder, in fact. The sad paradox lies in what might have been, all that potential when its creators had that first spark of inspiration. With a better handling of the camera, a tightening of the script, more attention to German military echelon and uniforms and, somehow, a kindling of real enthusiasm from both director Anatole Litvak and his actors, this “night” of a movie, as it were, might have made a craftily interesting World War II yarn.

Seems like a lot was against it.

Essentially a murder mystery during the Nazi occupation of Europe, the plot includes an uptight psychopathic general, a decent and tenacious military detective, a love story involving neither of them and a plot to kill Adolf Hitler. The plot was not one fabricated in the script, nor even one of the numerous minor assassination attempts against the Führer, but the most famous one—and the most disastrous for the almost 5,000 who were executed—the plot of July 20, 1944, led by Claus von Stauffenberg.

In at least one plus, the film is generally faithful to its source, Hans Hellmut Kirst’s 1965 novel, Die Nacht der Generale, translated into English as The Night of the Generals. The multiple layers of plot that are handled so well in the novel—Kirst (1914-1989) is always chillingly vivid in writing about the Third Reich and WWII—emerge, in the movie, as protracted, stodgy and confusing.

In at least one plus, the film is generally faithful to its source, Hans Hellmut Kirst’s 1965 novel, Die Nacht der Generale, translated into English as The Night of the Generals. The multiple layers of plot that are handled so well in the novel—Kirst (1914-1989) is always chillingly vivid in writing about the Third Reich and WWII—emerge, in the movie, as protracted, stodgy and confusing.

Maurice Jarre writes a deliberately jarring, one might say even ugly, main title, with a disjointed introduction of drums and cymbals, followed by the repeated five-note “insanity” motif that will underline the psychological, even psychopathological, overtones of the film. This motif is mingled with a fragmentary, goose-stepping march and the equally vague suggestions of a waltz.

The film opens in 1942, in the dark and narrow staircase of a Warsaw hotel. The absence of music in the first scene is doubly effective. All that is heard are the heavy footsteps, intentionally amplified, of a hotel clerk. The man hears a commotion—a woman’s scream, a door close, hurried footsteps—and, knowing to be prudent in Nazi-occupied Warsaw, hides in a water closet. Through a hole in the door he can see only the lower half of the man who descends the stairs—and the familiar uniform of a German officer, trousers distinguished by a red stripe.

A German military investigator, Major Grau (Omar Sharif), arrives to find the grisly sex murder of a prostitute, who also happens to be a German agent. He is an idealist, a seeker of justice, whoever the murderer. When the Polish police inspector, Liesowski (Yves Brainville), who summoned Grau to the scene asks if justice also applies to Germans, Grau replies, “If the general is responsible, I shall have to hang him.” Hearing the clerk’s description of the trousers, Grau knows that only German generals’ uniforms have the red stripe.

A German military investigator, Major Grau (Omar Sharif), arrives to find the grisly sex murder of a prostitute, who also happens to be a German agent. He is an idealist, a seeker of justice, whoever the murderer. When the Polish police inspector, Liesowski (Yves Brainville), who summoned Grau to the scene asks if justice also applies to Germans, Grau replies, “If the general is responsible, I shall have to hang him.” Hearing the clerk’s description of the trousers, Grau knows that only German generals’ uniforms have the red stripe.

The film switches briefly to 1965. Liesowski is reminiscing with Paris police inspector, Morand (Philippe Noiret)—nobody has first names here. Morand fought for the French Resistance during the war but became friends with Grau. The two exchanged favors, the Frenchman providing information about Nazi generals, the German facilitating the release of Resistance fighters. Liesowski recalls that of the generals in Warsaw in 1942 on the night of the murder, three were without alibis.

Back to Warsaw, 1942. Two of the generals are invited to a soirée hosted by the third, General von Seidlitz-Gabler (Charles Gray), and his abrasive wife (Coral Browne). The other two generals are Kahlenberge (Donald Pleasence, who would play another Nazi, Heinrich Himmler, in a better film, The Eagle Has Landed, in 1976) and Tanz (Peter O’Toole), the arrogant commander of the Nibelungen panzer division and a fanatical germaphobe.

Back to Warsaw, 1942. Two of the generals are invited to a soirée hosted by the third, General von Seidlitz-Gabler (Charles Gray), and his abrasive wife (Coral Browne). The other two generals are Kahlenberge (Donald Pleasence, who would play another Nazi, Heinrich Himmler, in a better film, The Eagle Has Landed, in 1976) and Tanz (Peter O’Toole), the arrogant commander of the Nibelungen panzer division and a fanatical germaphobe.

At the beginning of the party, any original Jarre music is put aside for “Entry of the Guests” from Richard Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser.

At the soirée is a young, unambitious corporal, Hartmann (Tom Courtenay), who had rather remain a corporal than become an officer. He has been recruited by General Kahlenberge to play the piano, though, strange, at the party no piano is heard, only band music. “Too skinny” and not especially attractive but with a strange fascination for women, as Hartmann’s cousin, Otto (Nigel Stock), observes, the corporal meets and quickly beds Ulrike (Joanna Pettet), Seidlitz-Gabler’s daughter. He confides to her that he is a coward, that he really didn’t kill those forty Russians for which he received the Iron Cross. (A good portion of their sex scene was deleted, thanks to the current Production Code.)

About this time, Grau is promoted to lieutenant colonel and reassigned to Paris on the recommendation of Kahlenberge. This is one of several possible red herrings strung throughout the film, including General Seidlitz-Gabler’s wife finding a “red stain” on his uniform. For that matter, after receiving dossiers on all three generals from Inspector Morand, Grau deduces about Tanz: “He revels in death, which is why, in a curious way, I don’t think he’s the man I’m looking for. Any one who has the power to destroy a city whenever he chooses doesn’t need such minor sport as killing a girl. I could be wrong, of course.”

A shift now to 1944. All three generals are in Paris. When Tanz’s driver is ousted for improperly cleaning the general’s shoes, Hartmann assumes the position at the request of Kahlenberge, who orders him to give Tanz a tour of Paris, mainly to keep the “Butcher of the Eastern Front” occupied, as Kahlenberge is involved in the plot to kill Hitler at Rastenburg. Several times Kahlenberge pressures Seidlitz-Gabler to join the conspiracy, but he prefers to wait before committing himself.

A shift now to 1944. All three generals are in Paris. When Tanz’s driver is ousted for improperly cleaning the general’s shoes, Hartmann assumes the position at the request of Kahlenberge, who orders him to give Tanz a tour of Paris, mainly to keep the “Butcher of the Eastern Front” occupied, as Kahlenberge is involved in the plot to kill Hitler at Rastenburg. Several times Kahlenberge pressures Seidlitz-Gabler to join the conspiracy, but he prefers to wait before committing himself.

When Kahlenberge asks Hartmann if he knows some nightclubs or girls for Tanz’s pleasure, Hartmann says he doesn’t really know the general’s tastes. Then Kahlenberge delivers one of the best lines in the film—there aren’t many: “Let us hope that whatever it is, it isn’t you, corporal. However, if it should be you, remember that you’re serving the fatherland.”

Before the tour, Tanz’s aide warns Hartmann to avoid cemeteries, tombs and any mention of death; he does pretty well until he alludes to the beheadings of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette as they pass the Place de la Concorde. Drinking and smoking in the back seat, seemingly in a half-stupor, his left eye twitching, Tanz seems not to notice.

Hartmann fares less well in guiding his charge through the Jeu de Paume museum. Entering a room of Nazi so-called “decadent” art, so decadent it is reserved for Reichsmarschall Göring, no doubt for his Karinhall castle, the pair pass paintings by Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir, Gauguin, Degas—— Tanz freezes before one painting and Hartmann reads from the guide book: “Vincent van Gogh. Self-portrait, Vincent in Flames. Painted while in an insane asylum.” Tanz seems to go into a trace. He sweats, he shakes, his left eye twitches. He extends a trembling, fumbling left hand—always gloved—as if to steady himself. Hartmann takes his arm. Tanz pulls back and shouts, “How dare you touch me! Never do that again!”

Hartmann fares less well in guiding his charge through the Jeu de Paume museum. Entering a room of Nazi so-called “decadent” art, so decadent it is reserved for Reichsmarschall Göring, no doubt for his Karinhall castle, the pair pass paintings by Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir, Gauguin, Degas—— Tanz freezes before one painting and Hartmann reads from the guide book: “Vincent van Gogh. Self-portrait, Vincent in Flames. Painted while in an insane asylum.” Tanz seems to go into a trace. He sweats, he shakes, his left eye twitches. He extends a trembling, fumbling left hand—always gloved—as if to steady himself. Hartmann takes his arm. Tanz pulls back and shouts, “How dare you touch me! Never do that again!”

That night in a nightclub, Tanz meets a prostitute, returns to the car and asks Hartmann to invite her to join him. He takes her to her apartment while his driver waits at the car. Tanz calls him up and shows him the sexually mutilated body. By asking Hartmann to pick up the woman, placing his identity discs (dog tags) near the body and getting the corporal’s fingerprints on a wine glass, he has successfully framed him. Tanz points his gun at him, gives him some money and orders him to desert, or be killed. Hartmann flees.

“The body lay in the middle of the room between the table and the bed. Anyone looking at it from the door would have mistaken if for a bulging sack. It lay huddled up, face buried in the carpet.” —— the opening of Hans Hellmut Kirst’s The Night of the Generals.

In the meantime, the plot to kill Hitler during a staff meeting at his East Prussian headquarters at Rastenburg has failed. A recent recruit in the conspiracy, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (Christopher Plummer in a single-scene, throw-away role) is seriously injured when a British plane strafes his staff car. The fate of Rommel, who eventually recovered from those injuries, is well known, but that of the movie plotters is left unexplained. In fact, the leader (in the film) of the conspirators, General von Stülpnagel (played by Harry Andrews), a real person, was hanged for this singular disrespect toward his Führer.

Ironically, at the moment Grau deduces that General Tanz, after all, is the murderer he is seeking and confronts him at his headquarters, the survival of Hitler is announced on the radio and Tanz shoots the colonel at point-blank range, proclaiming him to be one of the conspirators.

The film returns to 1965, now at the Hamburg international airport. General Kahlenberge, who has obviously survived the war but prefers his civilian title, arrives for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the creation of the Nibelungen division (a real unit, actually created in the last months of the war). Why Kahlenberge would wish to attend is a bit implausible, as he hated Tanz, who is the guest of honor at the celebration.

The film returns to 1965, now at the Hamburg international airport. General Kahlenberge, who has obviously survived the war but prefers his civilian title, arrives for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the creation of the Nibelungen division (a real unit, actually created in the last months of the war). Why Kahlenberge would wish to attend is a bit implausible, as he hated Tanz, who is the guest of honor at the celebration.

Inspector Morand meets Kahlenberge and asks if he remembers corporal Hartmann of years ago. Yes, he remembers him—and Grau. “When the whole world was tumbling about our ears,” he says, “there was Colonel Grau, mad as a hatter, trying to solve his little murders.”

There has been another grisly murder of a prostitute, now in Hamburg.

Morand is able to locate Ulrike through her father. She had married Hartmann, who is now a farmer, living under the name of Lutner.

As the old soldiers file in for the Nibelungen festivities, Carl Tieke’s march Alte Komeraden (Old Comrades) is played. Tanz is called from the stage and confronted by Morand, who provides, as the general scorns, only circumstantial evidence about the murders of three prostitutes—in Warsaw in 1942, in Paris in 1944 and now in Hamburg. Morand continues, announcing that to the killing in Paris there was a witness. Hartmann steps forward. “Perhaps you should have killed me, general,” he says.

Jarre’s music—this is not one of his better scores—comes to the fore as Tanz, once again in his dazed mode, staggers and steadies himself against the wall after Hartmann’s appearance. The music is now dark and disorganized, and the viewer who has been paying attention is waiting, waiting for that often-heard five-note “insanity” motif to emerge from the orchestral muddle. And, sure enough, it comes, changed now, less distinct, more disjointed—panicky, like the general’s own panic.

Cornered, Tanz asks for a revolver and does the right thing, as all Nazis do, as readily as lighting a cigarette or combing their hair, when they know the jig is up.

Cornered, Tanz asks for a revolver and does the right thing, as all Nazis do, as readily as lighting a cigarette or combing their hair, when they know the jig is up.

What a story, right? More accurately, what a story it might have been. At the foundations lie good ideas, with all sorts of possibilities, but Kirst’s tale is told unevenly, a bit incoherently; much is left to the imagination or to conjecture. The time changes between 1942 or 1944 and the then present of 1965 are often abrupt, not always clear.

The movement of players before the camera is sometimes unimaginative—actors strung in a line across the wide Panavision screen. This is not, after all, 1954, and by 1967 the use of the wide screen process had been refined, even, some feel, perfected within the inherent limitations of its aspect ratio. Many directors, to this day, abhor the format. The film’s French cinematographer, Henri Decaë, also shot at least three other English-language films on similar subjects, The Boys from Brazil, Castle Keep and a D-Day documentary.

Especially annoying is the sloppy dubbing, particularly disconcerting when the lips are out of sync or when an acoustic anomaly betrays a different time and location of a later re-recording, most common in long shots, say, when actors are walking down a hall. Even dialogue recorded at the time of filming is sometimes delivered in a matter-of-fact manner—that need for some enthusiasm from the players, as mentioned before.

The infamous salute “Heil Hitler!” is never rendered among the German officers until well into the film, and then only sporadically. When Grau enters the Warsaw hotel in the beginning, he and the guard at the entrance exchange traditional military salutes; the guard should have properly rendered the “Heil Hitler!,” Grau being an officer, for one.

The intended Waffen SS ranks shown are actually Wehrmacht ranks. On several occasions—for one, when Hartmann is driving Tanz around Paris—the swastika on flags and banners is backwards. Some of the shots of Paris during this drive are in black-and-white! The sloppy research in this Franco-British co-production is further evident in the German’s use of right-hand drive cars, including those for Tanz and Rommel.

Many scenes are unnecessary or protracted. The return to the tryst between Hartmann and Ulrike reveals nothing new, much like her nightclub meeting with a previous Hartmann girlfriend, unless as an excuse for some action in the brief Nazi raid. Tanz’s tanks destroying an old part of Warsaw, while Grau waits to speak to him, goes on far too long under the guise of “action,” though its valid purpose is to show the general’s cruelty. Tanz’s second visit to the museum, to stare and tremble once again before the van Gogh, is a long way around to prove, if that was its purpose, that the general had forgotten he had been there before.

A bad memory was not General Tanz’s problem.

It is just a pretentious bore. Like all lousy pictures, it could have been better.

Thanks for sharing this guilty pleasure. I don’t think it will go on my Must-See List, but I thoroughly enjoyed your analysis.

My all-time guilty pleasure is “Beach Blanket Bingo”. Don’t ask.

I find it a very fascinating film. Just watched it again.

Thanks for the extensive review.

Chris

Hi! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be ok. I’m absolutely enjoying your blog and look forward to new updates.|

Well to each his own! …I really liked this movie, it has a very original plot, grade “A” actors (although trying to think of Omar Sharif as a German Aryan is alittle stretch, but he does a pretty good job), and photography/sets were good. On my own scale of 1 to 10 (10 being the best) I’d rate this movie at an 8 …IMHO! (FYI – And I have a number of years on me and I’ve seen a thing or two)

Actually, Rommel’s car is left-hand drive, a six-wheeled Mercedes G4. I dunno why you remember it being right-hand drive. Tanz’s cars used in the film are a 1936 Maybach (Warsaw) and a 1939 Renault Juvaquatre (Paris). They’re German and French respectively, both period accurate and appropriate to the locale apart from the location of their steering wheels, which I admit is curious.

Also, although never outright stated, Tanz is apparently transferred from the Wehrmacht to the SS between Warsaw and Paris. As to Wehrmacht officers giving the raised hand salute: they generally preferred the traditional salute among themselves, and in the scene you mention, both Grau and the soldier he salutes are Wehrmacht.

Hi, this RHD issue interested me particularly because my father was a Czech airman who confirmed to me that Czechoslovakia drove on the left until ‘Hitler arrived’,I have a photo of a 1930’s Tatra,Right hand drive,to prove it.I took the picture in a village in Hertfordshire about fifteen years ago. I’ve looked up the Maybach and found a site called osianama.com which shows a Maybach SW38 with Right hand drive so they were obviously made in this configuration,even though Poland was apparently otherwise LHD at this time. As for the Renault,they were built in both LHD and RHD,I presume that the only cars the film makers could source were RHD,thankyou so much for identifying them in the first place! cheers,Steven Liska.

At Hamburg Airport after the war Morand meets up with ex General Kahlenberge who survived the war. Considering the fact that Kahlenberge was involved in the plot to kill Hitler I doubt he would have survived the subsequent round up after the failed attempt on Hitler’s life. Almost five thousand individuals were executed and I doubt if Kahlenberge would have escaped alive. As for General Tanz in charge of the Niberlungen division, the division was created March 27th 1945 while the attempt on Hitlers life was July 20 1944.

To each his own indeed. To quote Lina Lamont in SINGIN IN THE RAIN:

“I liked it.” Of course I was 14 when I saw it.

What was a “pretentious bore” was the initial review of this extraordinary film and the flimsy comments which followed.