The fly with the head of a man! And the man with the head of a fly!

The fly with the head of a man! And the man with the head of a fly!

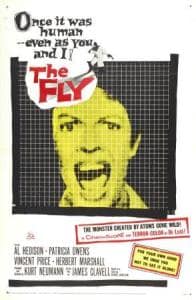

When watching The Fly, despite all that has happened earlier, much of it well done and sophisticated for a horror movie of its 1958 vintage, I always anticipate an especially favorite scene toward the end. Even though it borders on the comic, this plot moment is important, as it vindicates a wife’s fantastic, unbelievable tale and saves her from arrest for murder.

She claims—the movie is told in flashback—that her scientist-husband, in experimenting with teleportation, had unknowingly allowed a common housefly into the transference chamber with him, and he had emerged with the head and left claw of a fly. Most effectively, his new, mutated appearance is not seen until long after the fact, the dramatic and horror peak of the film.

The unfortunate scientist, André Delambre, is played by David Hedison, his distraught wife Helene by Patricia Owens, their son Philippe by child actor Charles Herbert. André’s brother François is played by Vincent Price, taking third place in the cast listings and here in a straight, sympathetic, non-horror role.

As for the climactic scene of reference, it occurs after André has been killed—not died, but been killed (assisted suicide, actually)—following an unsuccessful search for that other occupant of the teleporter. Not seen until toward the end of the film, the fly, in this cross-fertilization of mangled genes, has the scientist’s head and left hand. André hopes that, if the two passed through the machines again, they will emerge whole, their two respective species intact.

Not long before film’s end, François had sat out in the garden on a bench beside a bush with a spider web, and had demurely idled away the time without noticing the web or hearing, as the audience clearly hears, the little cry of “Help me! Help me!” The fly/human is about to be devoured by, to it/him, a giant brown spider.

Not long before film’s end, François had sat out in the garden on a bench beside a bush with a spider web, and had demurely idled away the time without noticing the web or hearing, as the audience clearly hears, the little cry of “Help me! Help me!” The fly/human is about to be devoured by, to it/him, a giant brown spider.

In an interview, Alfred Hitchcock had once discussed the difference between a momentary scare and extended suspense, and illustrated the second with a scene where a group of people talk idly, unaware of the bomb under their seat. “Don’t just sit there,” Hitchcock told them. “There’s a bomb under your seat!” In much the same way, viewers of The Fly must’ve been crying out, at least in their minds, for François to quit lollygagging, look around, see the fly and rescue André. “Rescue” is perhaps the wrong word; just do something.

Soon after this scene, just as his mother is about to be hauled away by the police for supposedly murdering her husband, the much more cognizant Philippe is able, somehow, to envision a spider web as a possible trap for a fly! Children are sometimes, after all, more perceptive than their parents. Philippe witnesses the garden tragedy about to happen and rushes upstairs to François and police inspector Charas (Herbert Marshall). He’s found the white-headed fly in the garden!

Soon after this scene, just as his mother is about to be hauled away by the police for supposedly murdering her husband, the much more cognizant Philippe is able, somehow, to envision a spider web as a possible trap for a fly! Children are sometimes, after all, more perceptive than their parents. Philippe witnesses the garden tragedy about to happen and rushes upstairs to François and police inspector Charas (Herbert Marshall). He’s found the white-headed fly in the garden!

François, who by now believes Helene’s story, begs the unconvinced inspector to go down to the garden and just see—what’s he to lose? The two men bend over the web and see this uncharacteristically sluggish spider—still only “about” to consume the white-headed fly during the long interval since François’ bench-warming. They hear the small, faint “Help me! Help me!” Charas picks up a large rock and crushes both fly and spider.

As Price was to remember years later, it required a number of takes before the scene was properly recorded, since he and Marshall kept cracking up.

As Price was to remember years later, it required a number of takes before the scene was properly recorded, since he and Marshall kept cracking up.

All this was near the end of the film, but, now, to approach the film from the beginning——

The Fly opens when André is found, apparently murdered, his head and left arm crushed in a factory hydraulic press. His wife Helene confesses, but provides no details. Rather, she seems obsessed with finding a white-headed fly, and thinking François is aware of everything, she relates their idyllic family life and André’s death.

Thus in flashback——

André’s life centers around his experiments with teleporting, first, using small inanimate objects, then a guinea pig and even Philippe’s pet cat. Things go generally well, though the cat fails to materialize; only a disemboweled “meowing” remains of the feline. An omen of things to come, perhaps? Still convinced all is well, André builds two larger teleporters, a sender and a receiver, large enough for himself.

André’s life centers around his experiments with teleporting, first, using small inanimate objects, then a guinea pig and even Philippe’s pet cat. Things go generally well, though the cat fails to materialize; only a disemboweled “meowing” remains of the feline. An omen of things to come, perhaps? Still convinced all is well, André builds two larger teleporters, a sender and a receiver, large enough for himself.

After André has remained in his workshop for a few days, a concerned Helene enters and finds him with a black cloth draped over his head and a hairy-looking left hand, which he keeps in the left pocket of his white laboratory coat. He cannot speak though he retains his mind. To communicate, he writes on the blackboard or uses a typewriter. In this way, he tells her an unseen fly was in the machine when he was transported and that their molecules became jumbled. She must, he urges, find and capture the fly.

After much searching, Helene and Philippe find the white-headed fly in the living room, and even recruit the maid (Kathleen Freeman) to help capture it. It eventually escapes through a crack in a window pane.

Time is running out for André, who is losing control of his mind, the instincts of the fly slowly taking over. He cannot control the rampant claw, which he tries to contain in his coat pocket. When the black cloth drops off, the fly head is indeed impressibly horrible—and Owens renders a most convincing, horrific scream. (It is said that, already afraid of insects, she never saw the fly head until the day the scene was filmed. Like any number of his kind, director Kurt Neumann was not above using tricks and impositions to achieve the performances he desired from his actors.)

Time is running out for André, who is losing control of his mind, the instincts of the fly slowly taking over. He cannot control the rampant claw, which he tries to contain in his coat pocket. When the black cloth drops off, the fly head is indeed impressibly horrible—and Owens renders a most convincing, horrific scream. (It is said that, already afraid of insects, she never saw the fly head until the day the scene was filmed. Like any number of his kind, director Kurt Neumann was not above using tricks and impositions to achieve the performances he desired from his actors.)

With the fly still not found and fearing for his wife’s safety, André destroys his research papers and equipment and leads her to the hydraulic press. He sets the press, sprawls under the two large plates and motions for Helene to push the red “descend” button. She activates the machine, but the claw arm has fallen clear. She raises the plate and, with her eyes turned away, places André’s deformed arm back in the press. The heavy steel monolith descends once again.

With the fly still not found and fearing for his wife’s safety, André destroys his research papers and equipment and leads her to the hydraulic press. He sets the press, sprawls under the two large plates and motions for Helene to push the red “descend” button. She activates the machine, but the claw arm has fallen clear. She raises the plate and, with her eyes turned away, places André’s deformed arm back in the press. The heavy steel monolith descends once again.

The film returns to the present and Helene’s arrest for the murder of André. Then, as described earlier, the white-headed fly is found in the garden and killed. As François explains to Inspector Charas, in killing the fly/human, he is as guilty of murder as Helene is of killing the human/fly. Charas, shocked and now believing, drops the charges. “I shall never forget that scream as long as I live,” he says.

François becomes a family friend—wisely, no inference is made of a romantic liaison with the new widow—and the final scene occurs, seemingly appropriate, in the garden, with a somewhat heavily sentimental suggestion of a return to normalcy. François explains to Philippe that sometimes scientists like his father, in their efforts to explore the unknown, venture into areas at the risk of their lives.

François becomes a family friend—wisely, no inference is made of a romantic liaison with the new widow—and the final scene occurs, seemingly appropriate, in the garden, with a somewhat heavily sentimental suggestion of a return to normalcy. François explains to Philippe that sometimes scientists like his father, in their efforts to explore the unknown, venture into areas at the risk of their lives.

All the cast members handle their parts well, from Hedison and Owens as man and wife to Herbert as their son. Owens renders an especially standout, sincere performance. Herbert Marshall, who once played the suave leading man opposite the likes of Marlene Dietrich, Kay Francis and Bette Davis, has basically a walk-on part here, though he does what he can. A slight stiffness from his prosthetic leg—his right was lost in World War I—is obvious on a few occasions, though unobtrusive to someone unaware of his history.

The one cast member who seems—well, just a little out of place and uncommonly restrained is Vincent Price, mainly because moviegoers are used to him in horror roles of some kind. There had been pre-Fly movies—The Invisible Man Returns, The House of Seven Gables, Dragonwyck and House of Wax—that suggest the more familiar roles to come. But even after his entry into TV in the mid-’60s, his typecasting as a horror master, which the actor fully relished, didn’t really begin until the first of the Roger Corman/Edgar Allan Poe series with House of Usher. And thereafter there was no holding him back: besides more Poe, both from Corman and other directors, there came Scream and Scream Again, the Phibes films, Theatre of Blood, Madhouse, House of Long Shadows and so many, many others.

The one cast member who seems—well, just a little out of place and uncommonly restrained is Vincent Price, mainly because moviegoers are used to him in horror roles of some kind. There had been pre-Fly movies—The Invisible Man Returns, The House of Seven Gables, Dragonwyck and House of Wax—that suggest the more familiar roles to come. But even after his entry into TV in the mid-’60s, his typecasting as a horror master, which the actor fully relished, didn’t really begin until the first of the Roger Corman/Edgar Allan Poe series with House of Usher. And thereafter there was no holding him back: besides more Poe, both from Corman and other directors, there came Scream and Scream Again, the Phibes films, Theatre of Blood, Madhouse, House of Long Shadows and so many, many others.

If it’s perhaps not true for those youngsters who were appropriately petrified by The Fly in 1958, the 1986 remake by director David Cronenberg has become even more famous, mainly because of its repulsive, nauseating special effects. This version is more gross than scary.

If it’s perhaps not true for those youngsters who were appropriately petrified by The Fly in 1958, the 1986 remake by director David Cronenberg has become even more famous, mainly because of its repulsive, nauseating special effects. This version is more gross than scary.

The scientist/victim this time is “Seth” Brundle (Jeff Goldblum). He apparently teleports intact—no alien appendages or other dipterous symptoms—except he does, at first, notice a heightened stamina and sexual prowess, which his girlfriend Veronica (Geena Davis) seems to appreciate. He is able to walk on ceilings and gains other fly-like attributes, physical and mental, all to his advantage, or so Brundle thinks. True, all is well for a while. And then body parts—fingers, his nose, teeth—begin to come off. As the fly gradually takes over his body, his behavior becomes erratic and abusive, and he starts to lose control of his mind.

The relative innocence of the 1958 original, not that that should have been the aim of this remake, is largely lost very early on, not only through the nauseous visuals but in a number of entanglements and subplots—Brundle’s affair with another woman, his jealousy toward Veronica’s boss and former lover, an arm wrestling match that breaks his opponent’s arm and Veronica becoming pregnant. Her fear is that she might give birth to——

The relative innocence of the 1958 original, not that that should have been the aim of this remake, is largely lost very early on, not only through the nauseous visuals but in a number of entanglements and subplots—Brundle’s affair with another woman, his jealousy toward Veronica’s boss and former lover, an arm wrestling match that breaks his opponent’s arm and Veronica becoming pregnant. Her fear is that she might give birth to——

No, better not go there. Better to enjoy 1958’s The Fly. A bit slow-moving, not especially sophisticated in its special effects (by today’s standards) and with only sporadic moments of fright, and even then somewhat tepid (again, by today’s standards), but, hey!, the ’50s was a totally different time. In the ’50s, everything, everyone seemed . . . more innocent.