“It’s funny! It’s too funny! Becket is the only intelligent man in my kingdom, and he’s against me.”—— King Henry II (Peter O’Toole)

Musicals have always been a part of movie magic, as well as other genres, even those lying outside the standard staples of drama and comedy, say, the more specialized Western, science fiction and horror. Musicals especially ebb and flow with public taste and the times. Two appeared, already, among the Best Picture nominations of the second “running,” so to speak, of the Academy Awards in 1928-29, and the most recent Oscar-nominated musical, Les Misérables, premiered in 2012. The vogue, which, true, fluctuates over the years, reached a peak in the 1960s with West Side Story, The Music Man, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, Oliver!, Hello, Dolly!, among others. The box office and critical failure of Dolly!, along with Doctor Dolittle and a few others, signaled the decline of the musical, at least at that level of popularity.

Along with the musical, always present as well, and also with a vogue that ebbs and flows, is what might be called the extreme historical drama, often in epic style, that takes a cinema time traveler exceptionally far back—to two major periods, the medieval and the biblical. Sharing 1927 with another musical, the “first talking” movie, The Jazz Singer, there is also a now obscure ancient history mini-epic, The Private Life of Helen of Troy. Also in that year is The King of Kings by the most prolific biblical epic maker of all time, Cecil B. DeMille.

For purposes here, the biblical and other ancient history films, be they Roman, Egyptian or what have you, are eliminated. Among the remaining medieval flicks, then, some are dramatic masterpieces, others ponderous and bloated, some ridiculous, even absolutely hilarious, some strictly duels, battles and gore. The better, more literate ones include the two Shakespearean Henry Vs (1947, 1989), the typical tale of knights in Ivanhoe (1952), the stage-bound but excellent A Man for All Seasons (1966), the stylishly original Excalibur (1981), an intelligent history craftily disguised as the swashbuckler Braveheart (1995) and the immaculately filmed Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001-2003).

True, the list omits many worthy medieval films, for there is no room for all of them here. It’s tempting to include, for example, Ladyhawke, a 1985 sword-and-sorcerer extravaganza, with sumptuous sets and cinematography and an affair between charismatic lovers Rutger Hauer and Michelle Pfeiffer, who cannot get together because of an evil bishop’s curse. He inhabits the night as a wolf, she the day as a hawk. But the two elements that make it truly unique are both negatives: Matthew Broderick as a young thief talks to the camera in modern jargon and the rock score assembled by Andrew Powell is boomingly intrusive and both esthetically and anachronistically wrong.

True, the list omits many worthy medieval films, for there is no room for all of them here. It’s tempting to include, for example, Ladyhawke, a 1985 sword-and-sorcerer extravaganza, with sumptuous sets and cinematography and an affair between charismatic lovers Rutger Hauer and Michelle Pfeiffer, who cannot get together because of an evil bishop’s curse. He inhabits the night as a wolf, she the day as a hawk. But the two elements that make it truly unique are both negatives: Matthew Broderick as a young thief talks to the camera in modern jargon and the rock score assembled by Andrew Powell is boomingly intrusive and both esthetically and anachronistically wrong.

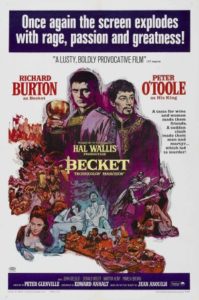

A list of medieval movie masterpieces must include Becket, one of the most literate of them all, medieval to its core, classy and classic, even classical in its dramatic prowess. Yes, even Shakespearean. That its source is a play by Jean Anouilh may partially explain its resemblance to the Bard of Avon—the struggle and pain of human conflict and the dramatic dialogue, more biting sometimes, if one should dare venture, than Shakespeare’s own. Not surprising, then, the movie won the Oscar in 1964 for Best Adapted Screenplay (Edward Anhalt). The conflicts between Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Macduff, between Richard II and his “cousin and foil” Bolingbroke or between Titus Andronicus and Tamora, the Queen of the Goths—they all seem to share proud, if tormented, company with the likes of Becket’s two larger-than-life protagonists, King Henry II and “his” Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas à Becket.

No Shakespearean history or tragedy includes any character named Henry II, certainly not an entire play devoted to the first of the Plantagenet kings. Henry and Eleanor of Aquitaine’s third son, portrayed in Richard I, would succeed his father, dying ten years later, and fifth son John and the next king would appear as the title character in Shakespeare’s King John. The Bard’s next play following the line of English monarchs—he skips four kings—is Richard II, the last of the Plantagenets. Sorry, this is not intended as a history or literature lesson!

This does bring up a forewarning, however, that the two-and-a-half-hour Becket is a bit wayward in historical accuracy, due both to the playwright and to the film’s production mistakes. Anouilh wrote his play before doing any research, and when later learning his errors, he decided to leave things as they were! So Becket was not a Saxon as depicted but a Norman, and the women’s costumes and the armor Henry’s boys wear playing games are of several centuries later. The famous Dies Irae, the Latin hymn for the dead heard in at least two scenes, was written the following century.

This does bring up a forewarning, however, that the two-and-a-half-hour Becket is a bit wayward in historical accuracy, due both to the playwright and to the film’s production mistakes. Anouilh wrote his play before doing any research, and when later learning his errors, he decided to leave things as they were! So Becket was not a Saxon as depicted but a Norman, and the women’s costumes and the armor Henry’s boys wear playing games are of several centuries later. The famous Dies Irae, the Latin hymn for the dead heard in at least two scenes, was written the following century.

Although not a mistake, because history would later prove it meaningless, King Henry II is seen in the film (correctly) crowning his eldest son as Henry III, primarily to spite Becket in moving the coronation to York, instead of the archbishop’s Canterbury Cathedral, then the traditional site of English coronations. This Henry III would die before his father, before he could take the throne. The eventual designated Henry III would be King John’s eldest son. Yes, it can be confusing!

If the viewer is expecting physical action and spattering blood in Becket, he will find little, except for two brief knife fights and the climactic murder in the cathedral, very realistic yet without being particularly bloody. Battles are actually avoided thanks to Becket’s diplomatic negotiations. Otherwise, it’s talk, talk, talk—but such intelligent, powerful, often rapid-fire dialogue could only come from a playwright, rarely from real life. Occasionally the vernacular is sometimes anachronistic, as “snack” sounds unseemly coming from the lips of a king, and, at the time, was not in use in referring to a small meal.

If the viewer is expecting physical action and spattering blood in Becket, he will find little, except for two brief knife fights and the climactic murder in the cathedral, very realistic yet without being particularly bloody. Battles are actually avoided thanks to Becket’s diplomatic negotiations. Otherwise, it’s talk, talk, talk—but such intelligent, powerful, often rapid-fire dialogue could only come from a playwright, rarely from real life. Occasionally the vernacular is sometimes anachronistic, as “snack” sounds unseemly coming from the lips of a king, and, at the time, was not in use in referring to a small meal.

Dropped into this swath of history, mistakes and all, are the pleasure-seeking King Henry II (Peter O’Toole) and his learned friend and companion in debauchery, Thomas Becket (Richard Burton). Laurence Rosenthal’s modern-tinged version of how medieval music might sound—church bell, brass and Gregorian chant—accompanies a lone, red-robed figure on horseback. He dismounts, climbs the entrance steps of Canterbury Cathedral, passes through the nave, descends into the crypt and to the tomb effigy of Thomas Becket. He removes his crown, robe and white undershirt. He kneels. King Henry II has come to do penance.

“Well, Thomas Becket, are you satisfied?” he begins. “Here I am, stripped, kneeling at your tomb while those treacherous Saxon monks of yours are getting ready to thrash me—me, with my delicate skin. . . . We did have a few fine summer evenings with the girls.”

“Well, Thomas Becket, are you satisfied?” he begins. “Here I am, stripped, kneeling at your tomb while those treacherous Saxon monks of yours are getting ready to thrash me—me, with my delicate skin. . . . We did have a few fine summer evenings with the girls.”

And now the film becomes a flashback. After escaping a village home when parents hear strange noises from their daughter’s bedroom, Henry and Thomas, as Henry calls him, return to the castle where the king bathes. Henry recognizes the change when Becket takes a servant’s place in rubbing down his back. “Ah! No one does it the way you do, Thomas.” (The first suggestion of a homoerotic relationship between the two men, a possibility substantiated by historical research. Homosexuality was still a crime in England in 1964; other even stronger hints occur later in the film that surprisingly passed the censors.)

At a council meeting with the Archbishop of Canterbury (Felix Aylmer), who protests a proposed tax on church property to support the king’s military forays in France, Henry decides to revive the office of Chancellor of England and appoints Thomas Becket. Becket argues that he is unworthy of the honor. “Rubbish,” the king replies. “You know more than all of us put together. He’s read books, you know. It’s amazing. He’s drunk and wenched his way through London, but he’s thinking all the time . . . ” All this is an unusually long scene, as are many in Becket.

At a council meeting with the Archbishop of Canterbury (Felix Aylmer), who protests a proposed tax on church property to support the king’s military forays in France, Henry decides to revive the office of Chancellor of England and appoints Thomas Becket. Becket argues that he is unworthy of the honor. “Rubbish,” the king replies. “You know more than all of us put together. He’s read books, you know. It’s amazing. He’s drunk and wenched his way through London, but he’s thinking all the time . . . ” All this is an unusually long scene, as are many in Becket.

The brief hunting jaunt that follows is merely an introduction to another long scene. The two men take refuge from a rainstorm in a peasant’s hut. They find a young girl (Linda Marlowe), and Henry, referring to her as “it,” decides to take her to the palace and “make her a whore.” Becket fancies the girl and so does the king. Henry relents and “gives” her to him. “But you will,” he says, “return the favor equally one day. . . . Equally, favor for favor.” Becket agrees.

Next, following a riotous banquet, Becket converses with his paramour, Gwendolen (Siân Phillips), a captive in the Norman’s defeat of the Welsh: “Somehow I can never support the idea of being loved. Where honor should be, in me there is only a void.” The king wanders in and demands the lady as part of their bargain, “favor for favor.” Becket asks for a moment with Gwendolen. “Surely. Surely,” Henry replies. “After all, I’m not a savage.”

Next, following a riotous banquet, Becket converses with his paramour, Gwendolen (Siân Phillips), a captive in the Norman’s defeat of the Welsh: “Somehow I can never support the idea of being loved. Where honor should be, in me there is only a void.” The king wanders in and demands the lady as part of their bargain, “favor for favor.” Becket asks for a moment with Gwendolen. “Surely. Surely,” Henry replies. “After all, I’m not a savage.”

Rather than submit to the king, Gwendolen stabs herself before Henry can reach her bed.

Henry complains that he doesn’t want to be alone that night and wonders if he can ever again trust his friend. Becket agrees to remain and, in almost “to be or not to be” fashion, ponders: “So long as Becket must improvise his honor from day to day, he will serve you faithfully. But what if one day he should meet his honor in truth, face to face?”

On French soil now, where Becket avoids battles and town sackings through his negotiations, he survives a knife attack by a Saxon monk, Brother John (David Weston), disgruntled by the chancellor’s deflection to the Normans (though, remember, Becket was a Norman). Becket orders him returned to his monastery—without brutality, he instructs.

On French soil now, where Becket avoids battles and town sackings through his negotiations, he survives a knife attack by a Saxon monk, Brother John (David Weston), disgruntled by the chancellor’s deflection to the Normans (though, remember, Becket was a Norman). Becket orders him returned to his monastery—without brutality, he instructs.

A messenger brings word to Henry that the Archbishop of Canterbury has died. The king has an “extraordinary idea.” And does he! He’ll avoid Church interference by naming “his man” as the new archbishop—Thomas Becket. “But I’m not even a priest!” “You can be ordained priest and consecrated archbishop the next day.” “I beg you, do not do this.”

Do it Henry does, and Becket gives away all his possessions as a symbol of his humility, calling it “the clumsy gesture of a spiritual gatecrasher.” Bishop Folliot (Donald Wolfit), the Bishop of London, warns him he cannot serve both Church and king, symbolized by the chancellor’s ring which he still wears.

Soon after becoming archbishop—the ritual photographed in reverent detail—Bishop Folliot brings news to Becket that a parish priest, who debauched a young girl, has been arrested by Lord Gilbert and turned over to the civil court, not to church authority as required. The priest is later killed in trying to escape. Becket has taken under his wing the still rebellious Brother John, who later overhears the archbishop in prayer and sees the sincerity of Becket’s godly purposes. Becket sends him to the king with a message demanding that Gilbert be charged with murder.

Soon after becoming archbishop—the ritual photographed in reverent detail—Bishop Folliot brings news to Becket that a parish priest, who debauched a young girl, has been arrested by Lord Gilbert and turned over to the civil court, not to church authority as required. The priest is later killed in trying to escape. Becket has taken under his wing the still rebellious Brother John, who later overhears the archbishop in prayer and sees the sincerity of Becket’s godly purposes. Becket sends him to the king with a message demanding that Gilbert be charged with murder.

Before Brother John can return with Henry’s reply, the king makes the five-hour horseback ride from London in four. Henry will not arrest Gilbert, but Becket plans to excommunicate him. Henry says, “I would have given away my life laughingly for you. Only I loved you and you didn’t love me.”

Before Brother John can return with Henry’s reply, the king makes the five-hour horseback ride from London in four. Henry will not arrest Gilbert, but Becket plans to excommunicate him. Henry says, “I would have given away my life laughingly for you. Only I loved you and you didn’t love me.”

Henry now summons Becket before his court on trumped-up charges of embezzlement. Becket declares he will put his case before the Pope in Rome. He and Brother John escape to France where King Louis VII (John Gielgud) gives Becket protection, then safe passage to Pope Alexander III (Paolo Stoppa). The Pope denies Becket’s request to relieve him of his ecclesiastic title, but will provide sanctuary in an abbey. But Becket, frustrated by the inactivity, offers a prayer to God. “I think you mean for me to defend your honor, peacefully if I can,” which means returning to England.

B oth on horseback, Becket and King Henry are reunited on a beach in France. They attempt small talk: he no longer derives pleasure in hunting and family life is no better. (The many scenes with his mother [Martita Hunt], wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine [Pamela Brown], and the four boys have been omitted in this summary. Unfortunate, as they contain some of O’Toole’s best tirades and personal abuses.)

oth on horseback, Becket and King Henry are reunited on a beach in France. They attempt small talk: he no longer derives pleasure in hunting and family life is no better. (The many scenes with his mother [Martita Hunt], wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine [Pamela Brown], and the four boys have been omitted in this summary. Unfortunate, as they contain some of O’Toole’s best tirades and personal abuses.)

“Look,” Henry says, “suppose we . . . use words that make sense to a boor like myself. Otherwise, we’ll never get anywhere and there’ll be two frozen statues trying to make their peace in a frozen eternity.” The “frozen statues” line is one that especially seems the overworkings of a playwright and, even more, alien to Henry’s persona; even coming from Becket, the line would be a stretch.

Henry grants Becket safe return to England and the archbishop agrees to all but one of the ten proposals which the Church accepted in his absence, except the one concerning the trying of wayward priests in the civil courts.

“You never loved me, did you, Thomas?” Henry asks.

“Insofar as I was capable of love—yes, I did.”

“Did you start to love God? . . . ”

“I started to love the honor of God.”

At another banquet, four of Henry’s knights overheard him mutter, “Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?” (Henry’s actual adjective was supposedly “turbulent.”) The knights, taking their cue from what was presumably a rhetorical question, enter the cathedral during vespers and slay both Becket and Brother John, who tries to defend him. Becket’s last words: “Oh, Lord, how heavy thy honor is to bear. Poor Henry.” Honor, honor—always about honor.

At another banquet, four of Henry’s knights overheard him mutter, “Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?” (Henry’s actual adjective was supposedly “turbulent.”) The knights, taking their cue from what was presumably a rhetorical question, enter the cathedral during vespers and slay both Becket and Brother John, who tries to defend him. Becket’s last words: “Oh, Lord, how heavy thy honor is to bear. Poor Henry.” Honor, honor—always about honor.

A return to the present. King Henry is lashed by the Saxon monks, his penance complete. He walks to the entrance of Canterbury Cathedral and announces that he had petitioned the Pope, and he has granted, that henceforth Becket will be prayed to as a saint. Henry returns to the crypt and lays a hand on those of Becket’s tomb effigy. “Is the honor of God washed clean enough? Are you satisfied now, Thomas?”

To no surprise in the decade of the musical, among the Oscar nominations in 1964 for Best Picture, Becket was up against not one but two musicals, the light little ditty Mary Poppins and My Fair Lady, formidable because of the heavy studio campaigning of its producer Jack L. Warner. Becket was further disadvantaged, being British-made. The good Lady received eight Oscars, including Best Picture, Becket only the Adapted Screenplay from among its twelve nominations. O’Toole’s and Burton’s Best Actor nominations essentially canceled each other out for an easy, and inevitable, win for Rex Harrison for Lady. Becket’s other unrewarded nominations include those for director Peter Glenville, cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth and composer Rosenthal. In retrospect, as happens so often in Academy history, time has proven, as it was clear to many in 1964, that Becket is the better film. But there again, two hugely different types of films, unfair to compare.

To no surprise in the decade of the musical, among the Oscar nominations in 1964 for Best Picture, Becket was up against not one but two musicals, the light little ditty Mary Poppins and My Fair Lady, formidable because of the heavy studio campaigning of its producer Jack L. Warner. Becket was further disadvantaged, being British-made. The good Lady received eight Oscars, including Best Picture, Becket only the Adapted Screenplay from among its twelve nominations. O’Toole’s and Burton’s Best Actor nominations essentially canceled each other out for an easy, and inevitable, win for Rex Harrison for Lady. Becket’s other unrewarded nominations include those for director Peter Glenville, cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth and composer Rosenthal. In retrospect, as happens so often in Academy history, time has proven, as it was clear to many in 1964, that Becket is the better film. But there again, two hugely different types of films, unfair to compare.

After hearing Rosenthal’s music, it’s hard to understand why the main producer, Hal B. Wallis, wanted someone else to score the film. With lightening change, the composer always finds just the proper touch in conveying heroism (what little there is), pageantry (there is much), moments of religious feeling (in the ecclesiastic settings and from Becket himself) or distressed anger (mainly from Henry). It is tempting to compare this score with John Barry’s The Lion in Winter, made four years later. Rosenthal’s music has a warmer brilliance. His use of a basic modern orchestral texture seems to fit more comfortably into the medieval milieu.

After hearing Rosenthal’s music, it’s hard to understand why the main producer, Hal B. Wallis, wanted someone else to score the film. With lightening change, the composer always finds just the proper touch in conveying heroism (what little there is), pageantry (there is much), moments of religious feeling (in the ecclesiastic settings and from Becket himself) or distressed anger (mainly from Henry). It is tempting to compare this score with John Barry’s The Lion in Winter, made four years later. Rosenthal’s music has a warmer brilliance. His use of a basic modern orchestral texture seems to fit more comfortably into the medieval milieu.

Peter O’Toole’s performance of Henry in Becket is much the same as in The Lion in Winter. He gives, at one extreme, the same subtle delivery, as when he tells Becket after taking possession of Gwendolen that he’s “not a savage.” At the other extreme—too often, perhaps—he shouts, thinking that makes the lines, the context, more dramatic. He’s more than adequate as the spurned lover, now wailing, now shouting, while Becket seems impassive. O’Toole well conveys the impression that he sees Henry as a really nice guy, but underneath, in the treatment of his wife, mother and children and, foremost, his abuse of Becket’s friendship, he betrays his true barbarism, which he must fearfully suspect is also part of his nature. It’s a sharp contrast to the intelligent and cultured Becket, whatever his faults.

Richard Burton’s performance, in contrast to his co-star’s, is altogether different, rock-solid in its delivery, contained, emulating something of the Shakespearean manner—clear diction, making every word count, especially in his monologues, in his prayers or when he thinks aloud to himself. This technique can be overdone, becoming detrimental and given to heaviness. Fortunately, he stops short of, say, Laurence Olivier’s technique of playing to the audience, with exaggerated gestures and a projection more suited to the stage. Finding just the right tone, then, Burton expertly reflects inward, a man in search of his honor and a way to love, key themes of the film. While O’Toole almost always shows what he feels, the viewer is never sure of Burton. How, for example, does his character feel about Gwendolen’s death and the king’s part in it, which has to motivate some of his later actions? Is he vengeful, angry, moderately upset or does he care?

Richard Burton’s performance, in contrast to his co-star’s, is altogether different, rock-solid in its delivery, contained, emulating something of the Shakespearean manner—clear diction, making every word count, especially in his monologues, in his prayers or when he thinks aloud to himself. This technique can be overdone, becoming detrimental and given to heaviness. Fortunately, he stops short of, say, Laurence Olivier’s technique of playing to the audience, with exaggerated gestures and a projection more suited to the stage. Finding just the right tone, then, Burton expertly reflects inward, a man in search of his honor and a way to love, key themes of the film. While O’Toole almost always shows what he feels, the viewer is never sure of Burton. How, for example, does his character feel about Gwendolen’s death and the king’s part in it, which has to motivate some of his later actions? Is he vengeful, angry, moderately upset or does he care?

The real King Henry II, the founder of English common law, retained most of his power over the Church, and despite clever maneuvering during most of his thirty-five years on the throne (one of the better reigns in British history), he suffered ultimate defeat at the hands of his family. Son Richard, in league with King Philip II of France, organized a rebellion and forced Henry to surrender. The king died two days later, July 6, 1189, at Chinon in France.

The real King Henry II, the founder of English common law, retained most of his power over the Church, and despite clever maneuvering during most of his thirty-five years on the throne (one of the better reigns in British history), he suffered ultimate defeat at the hands of his family. Son Richard, in league with King Philip II of France, organized a rebellion and forced Henry to surrender. The king died two days later, July 6, 1189, at Chinon in France.

As for Thomas Becket, he was canonized by Pope Alexander three years after his death, and his tomb at Canterbury Cathedral soon became the prime national shrine of England throughout the Middle Ages. It was rumored at the time that blood-soaked pieces of Becket’s vestments could cure diseases. Afraid that the body might be stolen, the monks placed his marble sarcophagus in the crypt and surrounded it with a stone wall, with two openings large enough for pilgrims to insert their heads to kiss the coffin.

Maybe an historical movie like Becket can best be appreciated, after all, with . . . a history lesson.

Beckett and it’s sequel The Lion in Winter have two things in common

1. Both were Best Picture nominees

2. Both lost to one of 2 musical nominees

My Fair Lady danced all night and upstaged both the supercalifragilisticexpialidocious Mary Poppins and Beckett while Oliver! picked a pocket or two to rain on the parades of both Funny Girl and The Lion in Winter

In regards to the “homoerotic” relationship between Becket and Henry, suggested by some of the dialogue: such a relationship was possible of course, but it’s also possible that we in the present are locked into the skewed concept of expressions of love being romantic in nature only. There was a time when a man could say that he loved another man, or when a woman could say that she loved another woman, without anything sexual or romantic in nature being attached to that. “Love” has a whole range of connotations when set in the context of a deep friendship. It doesn’t always lead to a bed.

“Becket” is one of my favorite films, despite having historical inaccuracies, as you’ve pointed out. One that I noted can be seen in the scenes in which Thomas is consecrated as archbishop. On the high altar is a veiled tabernacle, used to hold consecrated bread – the Body of Christ – in reserve. In the 12th century, this reserved sacrament was either suspended over the altar in a pyx, or more commonly, was kept in a niche in a nearby wall. Tabernacles weren’t generally placed ON altars until the 16th century. On the other hand, the vestments worn by Becket in these scenes were spot on. When a man today becomes a deacon, he wears a dalmatic. When he becomes a priest, he wears a chasuble. In the Middle Ages in regards to clerical vestments, all signs of rank were kept and worn as progression up the ladder was made, so Becket correctly wears his chasuble over a dalmatic.