“Well, I certainly ain’t tryin’ to make a gentleman out of ya. But I’m gonna be a lady if it kills me.”—— Kitty (Jean Harlow) to husband (Wallace Beery)

“Well, I certainly ain’t tryin’ to make a gentleman out of ya. But I’m gonna be a lady if it kills me.”—— Kitty (Jean Harlow) to husband (Wallace Beery)

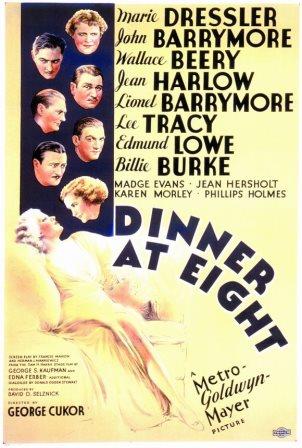

Dinner at Eight had practically everything going for it—directed by George Cukor, produced by David O. Selznick, based on a Broadway hit, a screenplay by three top-notch Hollywood writers, photographed by the great William H. Daniels and featuring practically every stellar star of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio. But it received not the first Oscar nomination in any category.

And this was in the early history of the Academy when there were ten nominations for Best Picture. Of the ten, the best-remembered today are Forty-Second Street, Little Women (for which Cukor was director-nominated), The Private Life of Henry VIII and, still a powerful indictment of criminal injustice, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang. The Best Picture winner, Cavalcade, about a married couple who witness history from 1899 through 1933 and with a score saturated with a variety of music, is hardly thought of today.

1932-33 was the last of the six “years” when the Oscar Academy eligibility voting period ran from August to August. In 1933 the voting period was extended through the last of December, so that this illogical confusion could be corrected January 1, 1934, when the Oscars would be awarded for films made during the calendar year.

The film’s Broadway source is the George F. Kaufman-Edna Ferber play of the same name, which had run for 232 performances after its opening in 1932. The film has a screenplay by Frances Marion and Herman J. Mankiewicz, with additional dialogue by Donald Ogden Stewart, whose witticisms preserve the flavor of the play. Stewart received his only Oscar as the sole screenwriter for The Philadelphia Story(1940).

The film’s Broadway source is the George F. Kaufman-Edna Ferber play of the same name, which had run for 232 performances after its opening in 1932. The film has a screenplay by Frances Marion and Herman J. Mankiewicz, with additional dialogue by Donald Ogden Stewart, whose witticisms preserve the flavor of the play. Stewart received his only Oscar as the sole screenwriter for The Philadelphia Story(1940).

If Grand Hotel, made by the same studio the year before and with many of the same players, is a cross-section of humanity at a hotel, then Dinner at Eight is its double. It looks into the lives of those invited to a plush dinner party, guests both sophisticated and unsophisticated, both ambitious and too dumb to be so. There is tragedy in some of their lives, but the impetus of the film, and what keeps it moving so capriciously, is its humor. The script is littered with many great, often cutting lines, a hilarious, great film.

Both films were made during the worst years of the Great Depression when movie themes were either escapist musicals and sweet love stories or gritty reflections of the hard times. Portraits of the suffering were, naturally, most often of those resilient souls who overcame their destitution, either through determination, strong character and hard work or through simple good lucky.

But Dinner at Eight is about the few days before the dinner. As in The Man Who Came to Dinner (1941), there is no climactic dinner, any more than there is one in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), when the participants enter the dining room on a camera pull-back and a fade-out. It’s all in the anticipation, the preparation. . . .

But Dinner at Eight is about the few days before the dinner. As in The Man Who Came to Dinner (1941), there is no climactic dinner, any more than there is one in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), when the participants enter the dining room on a camera pull-back and a fade-out. It’s all in the anticipation, the preparation. . . .

The hostess for the coming dinner at eight is the snobby, excitable Millicent Jordan (Billie Burke). Her husband, Oliver (Lionel Barrymore), a New York shipping tycoon, is far less taken with the dinner, and, unlike his wife, could care less about impressing the most notable invitees, Lord and Lady Ferncliffe, a coup for the social-climbing Millicent.

Oliver has more important things on his mind. He’s been hit hard by the Depression, and when another invited dinner guest, elderly, retired actress Carlotta Vance (Marie Dressler), asks him to buy her stock in the company, he doesn’t have the money. Oliver sees an out and asks wealthy Dan Packard (Wallace Beery) to buy some company stock. Unknown to Oliver, Packard, whose fortune is in mining, plans to double-cross him.

Oliver has more important things on his mind. He’s been hit hard by the Depression, and when another invited dinner guest, elderly, retired actress Carlotta Vance (Marie Dressler), asks him to buy her stock in the company, he doesn’t have the money. Oliver sees an out and asks wealthy Dan Packard (Wallace Beery) to buy some company stock. Unknown to Oliver, Packard, whose fortune is in mining, plans to double-cross him.

Oliver, hoping the dinner will impress Packard enough that he will buy his stock, suggests Millicent invite him and his wife, Kitty (Jean Harlow). Uncultured but socially ambitious, she is having an affair with Dr. Wayne Talbot (Edmund Lowe), while conducting endless shouting matches with hubby. “Politics! Ha!,” she screams at him. “You couldn’t get in anywhere. You couldn’t even get in the men’s room at the Astor!”

At the last minute, the meddling Millicent invites Larry Renault (John Barrymore). Renault is a faded, alcoholic movie star who brags he earned $8,000 a week at one time, but now has only seven cents in his pocket. The depiction reflects much of Barrymore’s actual life. Millicent is unaware that he is having an affair with her daughter, Paula (Madge Evans), who is expecting the return of her fiancé (Phillips Holmes) from Europe.

At the last minute, the meddling Millicent invites Larry Renault (John Barrymore). Renault is a faded, alcoholic movie star who brags he earned $8,000 a week at one time, but now has only seven cents in his pocket. The depiction reflects much of Barrymore’s actual life. Millicent is unaware that he is having an affair with her daughter, Paula (Madge Evans), who is expecting the return of her fiancé (Phillips Holmes) from Europe.

Renault, of course, has his own woes. Max Kane (Lee Tracy) informs him that his starring role in a planned theatrical appearance has been cancelled by the new producer (Jean Hersholt), who is willing, however, to give Larry a bit part. Larry now drinks even more.

Oliver’s troubles, in the short meantime, have increased. On the day of the dinner, when Oliver returns home from the doctor with a prognosis of terminal heart disease, Millicent is too distressed over a dinner setback to listen to her husband. Of all people, the Ferncliffes have cancelled and are headed for Florida. Possibly they have heard about a good deal on some stucco apartments, forgetting Groucho Marx’s warning, as recently as 1929, in Cocoanuts, about the Florida real estate boom in the 1920s: “You can have any kind of home you want. You can even get stucco. Oh, how you can get stuck-oh!”

And so the plot goes, with more complications, more setbacks for the various affairs in progress—this before Hollywood’s moral code became more restrictive—and some welcomed changes in people’s objectives.

And so the plot goes, with more complications, more setbacks for the various affairs in progress—this before Hollywood’s moral code became more restrictive—and some welcomed changes in people’s objectives.

It’s difficult to decide—and why want to?—who are the stars of this terrific ensemble of performers, which ones stand out. But, then, “standing out” isn’t the measure, nor the purpose, of a finely tuned group of actors. Here individual stars are all equally effective, even if, true, many are playing types of characters they have played before, some even to the point of typecasting.

Despite her age and weight, Marie Dressler was voted the most popular actress for three consecutive years—and this during the reigns of the current beauty queens, including Jean Harlow. Dressler won a Best Actress Oscar in 1930 for Min and Bill, starring opposite Wallace Beery.

Dressler’s character has a ready quip for any snide remark directed at her. In what can only be termed a “delicious scene” during those pre-dinner conversations, an elderly Miss Copeland (Elizabeth Patterson) has implied that she was only a child when she saw Carlotta, years ago, on the stage. Carlotta ends the conversation by suggesting that sometime they must discuss the Civil War, “Just you and I.”

Dressler’s character has a ready quip for any snide remark directed at her. In what can only be termed a “delicious scene” during those pre-dinner conversations, an elderly Miss Copeland (Elizabeth Patterson) has implied that she was only a child when she saw Carlotta, years ago, on the stage. Carlotta ends the conversation by suggesting that sometime they must discuss the Civil War, “Just you and I.”

John Barrymore, receiving second billing after Dressler, is clearly revisiting a frequent role, the cad, a man on the ropes, but still not too old to charm the ladies—any man’s lady. Despite the drinking and the premature aging, he still has intact that great profile, and cinematographer Daniels establishes at least one camera setup to display it. Barrymore is lying on a sofa in his monogrammed bathrobe, with lovely Madge Evans, sitting beside him, playing second fiddle.

Jean Harlow, who makes quite an impression despite her relatively small role, had been having a running feud with co-star Wallace Berry since they made The Secret Six in 1931. Their dislike of one another in real life helps make even more convincing their continual bickering as screen husband and wife. He says they’re not going to the dinner; she informs him that they are. “It’s the first chance,” she says, “I ever got with decent society people, to see my name in the paper with somebody that ain’t mixed in your dirty politics, and if I miss it, you’re going to pay for it with everything you’ve got.”

Jean Harlow, who makes quite an impression despite her relatively small role, had been having a running feud with co-star Wallace Berry since they made The Secret Six in 1931. Their dislike of one another in real life helps make even more convincing their continual bickering as screen husband and wife. He says they’re not going to the dinner; she informs him that they are. “It’s the first chance,” she says, “I ever got with decent society people, to see my name in the paper with somebody that ain’t mixed in your dirty politics, and if I miss it, you’re going to pay for it with everything you’ve got.”

The other stars—Wallace Beery, Lionel Barrymore, Lee Tracy, Edmund Lowe, Billie Burke, Jean Hersholt and Elizabeth Patterson—are excellent. Two others not mentioned deserve credit. May Robson, who played the Jordan’s cook, is especially well remembered as the grandmother who encourages Janet Gaynor to pursue her acting career in A Star Is Born (1937). Robson was nominated Best Actress in 1932-33 for Lady for a Day, losing to Katharine Hepburn for Morning Glory, her first Oscar. And Grant Mitchell, a reluctant dinner guest, will be even more disgruntled as the imposed upon homeowner in The Man Who Came to Dinner.

Of the many great lines in the film, the best is saved for last:

Carlotta, matronly and overweight, and Kitty, sleek in a tight-fitting gown, are walking toward the dining room—finally, after almost two hours of film. Kitty has said she had read a book, which, of course, surprises Carlotta. “A book?” she might have asked herself. “Read—this gal?”

Carlotta, matronly and overweight, and Kitty, sleek in a tight-fitting gown, are walking toward the dining room—finally, after almost two hours of film. Kitty has said she had read a book, which, of course, surprises Carlotta. “A book?” she might have asked herself. “Read—this gal?”

“Yes,” Kitty continues. “It’s all about civilization or something, a nutty kind of a book. Do you know that the guy said that machinery is going to take the place of every profession?”

Arching her back and casting an eye down her dining companion’s figure, Carlotta says, “Oh, my dear, that’s something you need never worry about.”

As the two women enter the dining room, the last of the guests, the servants close the double doors, and the viewer can only imagine what will transpire, now, among these guests. The fun, though, has been what occurred before the dinner!