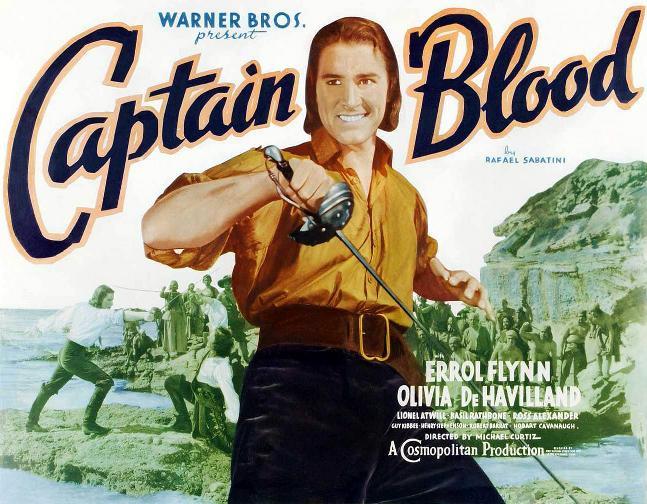

His sword carved his name across the continents – and his glory across the seas!

It’s been so long since Captain Blood was mint fresh, in 1935—seventy-five years ago in 2010, it will be—that its startling and, in some ways, revolutionary place in the history of Hollywood is often underestimated or, worse, overlooked.

True, from our modern perspective, the film has a number of negatives and seems a mite quaint—we are, after all, so sophisticated! Despite the latest restoration on DVD, the physical age of the film shows, and some of the sets and miniatures are, well, tacky. For some viewers, there’s the stigma of the black and white. All that talking could’ve been supplanted by today’s craving for more action. The mono sound is “pinched” and distorted, hardly capable of capturing the proper noise which all “good” films require. And the old-fashioned description frames, reminiscent of the days of the silents, date it as much as anything, though Gone with the Wind has them and manages to be a great film.

In retrospect—and try to sense those times: a rather naïve, depression-era, pre-WWII America—Captain Blood launched at least three careers: Errol Flynn’s, Olivia de Havilland’s and Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s. When Jack Warner and Hal B. Wallis, the savvy executive producer, one of the best in the business, were desperate to replace the originally scheduled title actor, Robert Donat, who became unavailable, they found their contract leading men either busy or wanting in the necessary persona. (Can anyone—well, anyone—imagine, in the title role, George Brent, who was considered?!) Blood was perhaps the most expensive Warner Bros. production of the year, and the Tasmanian actor the bosses finally selected would be a gamble.

In retrospect—and try to sense those times: a rather naïve, depression-era, pre-WWII America—Captain Blood launched at least three careers: Errol Flynn’s, Olivia de Havilland’s and Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s. When Jack Warner and Hal B. Wallis, the savvy executive producer, one of the best in the business, were desperate to replace the originally scheduled title actor, Robert Donat, who became unavailable, they found their contract leading men either busy or wanting in the necessary persona. (Can anyone—well, anyone—imagine, in the title role, George Brent, who was considered?!) Blood was perhaps the most expensive Warner Bros. production of the year, and the Tasmanian actor the bosses finally selected would be a gamble.

Flynn had only moderate acting experience. His roles in the four films he made since 1933 were small and somewhat unimpressive. Who remembers him as Fletcher Christian, for example. But he improved so rapidly in Blood that many early scenes were reshot. In fact, he ends up being quite good on screen, giving the impression of understanding his role, approaching his part, maybe, with the care of a Shakespearean actor. It’s a common appraisal but true: besides being able to flourish a sword better than anyone before or since, Flynn wore period clothes with style, as if he had stepped out of the past, or, as some have said, belonged there. His director, the Hungarian Michael Curtiz—of the fractured English and “bring-on-the-empty-horses” fame—told Flynn to tear some of that sissy lace from his 17th-century clothes, which Flynn did.

He spoke the convoluted lines naturally and with conviction. Not easy. The stilted quaintness and archaisms of the dialogue are largely retained from Rafael Sabatini’s 1922 novel, thanks to Casey Robinson’s screenplay. Yes, the words have a certain fascination because they are so quaint, so different from normal usage and seem to fit imagined 17th-century speech: “Faith, yes, I don’t doubt it. You’ve the looks and manners of a hangman.” “It’s entirely innocent I am.” “Bedad, we’ll have a crew yet!” “ . . . while I, who hate this pestilential island—well, such are the quirks of circumstance.” —All lines delivered by Flynn!

There are numerous asides in which Peter Blood usually looks heavenward or to one side of the camera. When he’s a prisoner aboard a slave ship: “It’s a truly royal clemency we’re granted, my friends, one well worthy of King James.” Though fellow slaves are present, he seems oblivious to them. When a Spanish pirate attack saves him from a flogging: “This is what I call a timely interruption, though what’ll become of it, the devil himself only knows.” When he’s toasted, now a pirate: “Well, bedad, methinks the ‘greatest captain on the coast’ has just made the greatest mistake the most ordinary, common fool could make.”

There are numerous asides in which Peter Blood usually looks heavenward or to one side of the camera. When he’s a prisoner aboard a slave ship: “It’s a truly royal clemency we’re granted, my friends, one well worthy of King James.” Though fellow slaves are present, he seems oblivious to them. When a Spanish pirate attack saves him from a flogging: “This is what I call a timely interruption, though what’ll become of it, the devil himself only knows.” When he’s toasted, now a pirate: “Well, bedad, methinks the ‘greatest captain on the coast’ has just made the greatest mistake the most ordinary, common fool could make.”

As for Olivia de Havilland, who had made only one previous film, A Midsummer Night’s Dream earlier that year, Blood offered a much larger role. Her girlish and virginal persona would endure essentially unchanged in the seven subsequent films she made with Flynn, and the two would become one of Hollywood’s great romantic screen couples, á la Tracy and Hepburn, Bogart and Bacall. The charisma between the two, immediately evident in Blood, persists resplendently in all their films.

Unfortunately, Olivia spent most of her screen time waiting for her love to return from somewhere. The plots of three of their films turn tragic. In The Charge of the Light Brigade, their next film after Blood, she prefers his buddy, Patric Knowles, and Flynn ends up dead. She is generally ignored by both Flynn and the camera in Elizabeth and Essex, where he is in a power struggle with Queen Elizabeth (Bette Davis), who sends him to the block. And death also awaits him in their last film together, They Died with Their Boots On—history rewritten, General Custer all hero, none of the fool.

Unfortunately, Olivia spent most of her screen time waiting for her love to return from somewhere. The plots of three of their films turn tragic. In The Charge of the Light Brigade, their next film after Blood, she prefers his buddy, Patric Knowles, and Flynn ends up dead. She is generally ignored by both Flynn and the camera in Elizabeth and Essex, where he is in a power struggle with Queen Elizabeth (Bette Davis), who sends him to the block. And death also awaits him in their last film together, They Died with Their Boots On—history rewritten, General Custer all hero, none of the fool.

The plot of Captain Blood, like the dialogue, is essentially faithful to the novel. It’s 1685, the Duke of Monmouth’s rebellion in England. A doctor, Peter Blood (Flynn), is convicted of treason but saved from the gallows and sold into slavery in Port Royal, Jamaica. He’s lucky again, this time spared the wrath of a brutal overseer by a charming lady, Arabella Bishop (de Havilland). Blood and his fellow slaves capture a Spanish galleon and become pirates. An impressive montage of ship boardings, duels, smoldering cannons and roaring music delineates his growing fame as a pirate, and on the screen, spaced at intervals:

In the pirate haven of Tortuga, Blood signs a compact with French rascal Levasseur (Basil Rathbone).

Blood’s and Arabella’s paths cross again on a beach where he soon dispatches his discontented partner. As Levasseur’s face is awash in the surf, Blood summarizes, “And that, my friend, ends a partnership that should never have begun.” Slosh, slosh. (Alert viewers will notice that the two separate clips are identical; Rathbone blinks his eyes in both.) Blood accepts a pardon/commission from the English king, defeats two French warships, becomes governor of Jamaica and wins the hand of—well, the rest is preordained!

Blood’s and Arabella’s paths cross again on a beach where he soon dispatches his discontented partner. As Levasseur’s face is awash in the surf, Blood summarizes, “And that, my friend, ends a partnership that should never have begun.” Slosh, slosh. (Alert viewers will notice that the two separate clips are identical; Rathbone blinks his eyes in both.) Blood accepts a pardon/commission from the English king, defeats two French warships, becomes governor of Jamaica and wins the hand of—well, the rest is preordained!

A Viennese composer of operas and chamber music, once a child prodigy, Korngold had worked with de Havilland on the Shakespeare movie arranging Mendelssohn’s music. Warner Bros. was so impressed they asked him to write an original score for a “little” movie they had just finished. Korngold, without seeing Blood, said no, but after WB’s insistence and a private screening, he was so moved by the film’s charm and humor that he agreed to write the music. What he didn’t know—what WB had failed to tell him—was that he had only three weeks.

With time running out, he borrowed parts of two Franz Liszt tone poems, Mazeppa and Prometheus, to support the noisy battle scenes, interspersed with previous Korngold music from the film. While movie composers today appropriate the classics as their own, usually without acknowledgment, Korngold insisted his main title credit read “Arrangements by Erich Wolfgang Korngold.” This automatically disqualified Blood for nomination as Best Score, which it surely would have received; the composer would win the next year for Anthony Adverse.

With time running out, he borrowed parts of two Franz Liszt tone poems, Mazeppa and Prometheus, to support the noisy battle scenes, interspersed with previous Korngold music from the film. While movie composers today appropriate the classics as their own, usually without acknowledgment, Korngold insisted his main title credit read “Arrangements by Erich Wolfgang Korngold.” This automatically disqualified Blood for nomination as Best Score, which it surely would have received; the composer would win the next year for Anthony Adverse.

Korngold had a large part—a very large part—in the overwhelming success of Captain Blood. A contemporary equivalent would be John Williams’ impact with Jaws (1975) or, even more so, the first of the Star Wars films (1977), which, in fact, is an obvious homage to the Korngoldian style—the lyrical, richly orchestrated, heart-on-sleeve ardor of 19th-century music. Take a listen below.

Audiences who first heard Blood were astounded. They had never heard such music, not even compared with Max Steiner’s ground breaking King Kong (1933). The orchestra which recorded the music to film, the studio heads who saw the completed movie before release and the public which attended the country’s theaters—none of them had ever heard such music from a motion picture—a large orchestra by studio standards, complicated orchestration, big, luscious sound, dramatic music that perfectly underpinned the screen. Blood remains a milestone in film scoring, and Korngold would contribute to six more Flynn films.

Blood and his crew setting sail from Port Royal is one of the most lingering images in the film. He and Arabella exchange forlorn glances, he from the ship, she from shore, captured in multiple dissolves and supported by Korngold’s swelling music, horns echoing at the conclusion. (The scene, by the way, is replicated in The Sea Hawk [1940], Korngold and Flynn in tandem, only with Brenda Marshall as a pale stand-in for Olivia.) Later, before the final sea battle, when Arabella is put ashore in a longboat, there’s a reprise of that first separation, the two again staring after each other, if not to swelling, then certainly to lushly romantic music—horns again prominent.

Blood and his crew setting sail from Port Royal is one of the most lingering images in the film. He and Arabella exchange forlorn glances, he from the ship, she from shore, captured in multiple dissolves and supported by Korngold’s swelling music, horns echoing at the conclusion. (The scene, by the way, is replicated in The Sea Hawk [1940], Korngold and Flynn in tandem, only with Brenda Marshall as a pale stand-in for Olivia.) Later, before the final sea battle, when Arabella is put ashore in a longboat, there’s a reprise of that first separation, the two again staring after each other, if not to swelling, then certainly to lushly romantic music—horns again prominent.

Most critics say that as early as Anthony Adverse and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) Korngold began experimenting with pitching the key of the music just beneath the actors’ voices. It began, actually, with Blood, if not sooner. Perhaps the best example, in any of his film scores, of how he unifies music with the screen image is the pillory scene between Blood and Jeremy Pitt (Ross Alexander), how the music—the second theme—changes in ambience, orchestration and volume, according to the emotions of the two men. Likewise, in the final love scene (“Whom else would I love?” Arabella asks), the music hesitates, softens, speeds up, becomes richer or changes in instrumentation, even disappears at one point, based on the tempo and emotion of the dialogue.

Complaint has been made, already, about the telltale use of models, and they are sometimes pathetic, as when Hagthorpe (Guy Kibbee) carronades the approaching longboats bearing the Spanish sailors, which, in the long shots, are clearly stiff, unmoving dolls. But in that final battle the intercutting between 18-foot model ships and the set-bound deck of Blood’s vessel, even seventy-three years later, is manifestly exciting and brilliantly edited.

Complaint has been made, already, about the telltale use of models, and they are sometimes pathetic, as when Hagthorpe (Guy Kibbee) carronades the approaching longboats bearing the Spanish sailors, which, in the long shots, are clearly stiff, unmoving dolls. But in that final battle the intercutting between 18-foot model ships and the set-bound deck of Blood’s vessel, even seventy-three years later, is manifestly exciting and brilliantly edited.

Somewhat related is the frequent admonition “beware of the 99-minute, cut print,” or something similar. Not so, not necessarily. Following the success of Gregory Peck’s Captain Horatio Hornblower in 1951, Blood was reissued in theaters, and it was, in fact, this edited print that was sold to television many years ago and which post-1930s generations came to know. However, both Ted Turner’s colorization in 1987 and the latest DVD incarnation restored the complete 1935 version.

Despite the expected revelations in the extra twenty minutes, there is little “new” Korngold music and, more important, the film is better, tighter, faster-paced with the cuts. Gone are Reverend Ogle’s intrusive misquoting of Scripture, the tedious detailing of the pirates’ reimbursement for loss of limbs, the ridiculous, languorous scene in which Blood’s crew threaten mutiny, are accommodated by the captain, then change their minds! Mercifully axed are parts of two scenes with tedious, implausible dialogue—the first half of a love scene on horseback and the last half of Blood’s finagling with two doctors about obtaining a boat. And more—and all for the good. The most crucial loss of Korngold music occurs early in the film, at Lord Gildoy’s, a variation on the main theme not subsequently repeated.

The humor that so impressed Korngold runs throughout the film. A recurring joke is Governor Steed’s (George Hassell) bout with the gout. Following a slave branding, the next shot shows the governor in a close-up. “What a cruel shame,” he says, “that any man is made to suffer so.” Whereupon the camera pans to his bandaged foot! Later, when Colonel Bishop (Lionel Atwill) replaces him as governor, Steed comments to his wife, “I hope he gets the gout the infernal office gave me.”

If 1935 isn’t quite in the league with 1939, Hollywood’s greatest year by all consensus, besides Blood and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the year also produced The Informer, Bride of Frankenstein, Top Hat, David Copperfield, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and another little sea saga, Mutiny on the Bounty.

No tribute to the period would be complete without mentioning those great, ever-reliable supporting players who populated the films of the ’30s and ’40s and who became almost like family to the mover-goers of the day. Captain Blood is easily the pre-eminent example: Guy Kibbee, Henry Stephenson, Robert Barrat, Hobart Cavanaugh, Donald Meek, Forrester Harvey, J. Carrol Naish, Pedro de Cordoba, Leonard Mudie, Jessie Ralph, Halliwell Hobbes, E. E. Clive and Holmes Herbert—names recognized by the faithful followers of films of the era.

No tribute to the period would be complete without mentioning those great, ever-reliable supporting players who populated the films of the ’30s and ’40s and who became almost like family to the mover-goers of the day. Captain Blood is easily the pre-eminent example: Guy Kibbee, Henry Stephenson, Robert Barrat, Hobart Cavanaugh, Donald Meek, Forrester Harvey, J. Carrol Naish, Pedro de Cordoba, Leonard Mudie, Jessie Ralph, Halliwell Hobbes, E. E. Clive and Holmes Herbert—names recognized by the faithful followers of films of the era.

Lionel Atwill, who plays Arabella’s uncle and, worse, Blood’s nemesis, is a notch about the supporting player category. A somewhat strange and sinister person off screen, he was the in-house villain, ready and willing to snarl and glare. He’s best remembered as the one-armed police chief in Son of Frankenstein (1939)—a precursor of Peter Sellers’ Dr. Strangelove? As a non-villain, Atwill exudes an impressive presence as Dr. Mortimer in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939), with Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes, though, even here, with his wire spectacles and thick lenses, he projects an air of malevolence.

Lionel Atwill, who plays Arabella’s uncle and, worse, Blood’s nemesis, is a notch about the supporting player category. A somewhat strange and sinister person off screen, he was the in-house villain, ready and willing to snarl and glare. He’s best remembered as the one-armed police chief in Son of Frankenstein (1939)—a precursor of Peter Sellers’ Dr. Strangelove? As a non-villain, Atwill exudes an impressive presence as Dr. Mortimer in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939), with Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes, though, even here, with his wire spectacles and thick lenses, he projects an air of malevolence.

Two curiosities in the film: A rather peculiar incident occurs during that climactic sea battle. Robert Barret, who plays first mate Wolverstone, rushes up to Blood amid cannon fire, crying, “We’ll never do it, Peter!,” and promptly throws his hat away, sending it sailing like a Frisbee. Now why? . . . Second, Halliwell Hobbes, who spent his life playing butlers and here plays Lord Sunderland, with speaking parts in two scenes, is absent from the cast credits, which come, unusually, before the film begins and not at the end. Stars with smaller roles, even “Slave” who says not a word, are listed!

A sad note was the suicide, at age thirty, of upcoming star Ross Alexander, who had appeared with de Havilland in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, his only film of distinction besides Blood. He made six films in 1936, all forgotten.

A sad note was the suicide, at age thirty, of upcoming star Ross Alexander, who had appeared with de Havilland in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, his only film of distinction besides Blood. He made six films in 1936, all forgotten.

Captain Blood ends with beautiful resolve, coming full circle, with charm and humor. When Bishop arrives from sea, Lord Willoughby (Henry Stephenson) informs him he is no longer governor, that his fate rests entirely with the new governor—inside. Bishop enters the room. Head bowed at a desk, Blood’s face is covered with his hands. With much exaggeration, Arabella wrings her hands and tells her uncle, “I’ve been pleading with the governor on your behalf, asking him to be as merciful as you would be cruel.” Extending her arm toward the bowed head, she says, “Uncle, this is the governor!”

Blood raises his head and smiles. “Good morning—uncle.” Bishop, dismayed and scowling, removes his hat and bows. He and Wolvestone must have a similar problem with hats, for Bishop reaches his left hand across his face and grabs the right side of the brim to remove his hat! Arabella kisses Peter Blood on the temple. THE END

This film, once watched, would—should—bring a smile to everyone, except perhaps the most hardened movie-goer. How could anyone say he has not, with Captain Blood, experienced a golden glow from Hollywood’s Golden Age, when everything wasn’t total reality and a tacky set didn’t disenchant make-believe? A fairy tale, this? Possibly. An old-fashioned romance? Definitely.

——————————————————————–

RECOMMENDED FOR FURTHER READING:

About Flynn:

Errol Flynn: The Life and Career by Thomas McNulty

The Films of Errol Flynn by Tony Thomas, Rudy Behlmer and Clifford McCarty

Two excellent works. McNulty’s is a bit pricey but worth every penny. Latter is out of print but readily available used from Amazon.

About Korngold:

The Last Prodigy: A Biography of Erich Wolfgang Korngold by Brendan G. Carroll. from Amazon.com: “Brendan Carroll’s excellent biography of this composer who was so shabbily ignored by postwar intellectuals is long overdue. From the outset, Carroll focuses on the phenomenal musical ability shown by Korngold. Not only did he produce complex musical compositions from an early age, but these early compositions are adult in style and show the distinct idiom of the composer. Like Mozart, Korngold’s distinguishing talent was an inexhaustible supply of melodic inspiration that he skillfully assembled.”

1997, Amadeus Press, Portland, Oregon, U.S.A.

RECOMMENDED FOR KORNGOLD CD LISTENING:

Captain Blood (a 20-minute suite), Victor Young’s Scaramouche and other film score suitesRichard Kaufman and the Brandenburg Philharmonic Orchestra

The Sea Hawk (complete: 110 mins.) and Korngold: Deception (complete)William Stromberg and the Moscow Symphony Orchestra and Chorus (2 CDs)

Two outstanding recordings of masterful compositions.

RECOMMENDED FOR FLYNN DVD VIEWING:

The Errol Flynn Signature DVD Collection Vol.1 (includes Captain Blood, The Sea Hawk, Dodge City, They Died with Their Boots On, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex)

The Errol Flynn Signature DVD Collection Vol.2 (includes The Charge of the Light Brigade, Dive Bomber, Gentleman Jim, The Adventures of Don Juan, The Dawn Patrol)