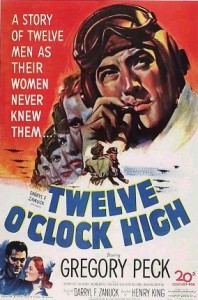

A story of twelve men as their women never knew them…

A story of twelve men as their women never knew them…

Command Decision is clearly a star vehicle for Clark Gable, convincing though he is as the no-nonsense commander. It’s a bit talkie, even involving political interference from a visiting congressman. The War Lover is another star vehicle, in this case for Steve McQueen, approaching tedium at times, with script and plot fatally subservient to him. Fatal, that is, as a war movie: as a love story, with McQueen and Robert Wagner contending for Sally Anne Field, it’s well acted (at least by the two male stars; Sally Field is pretty weak), though cliché heavy.

Twelve O’Clock High, easily superior to either of the two films cited, is, in fact, perhaps the best movie, ever, on the subject, and one of the great war films. Veteran WWII airmen who endured those bombing raids over France and Germany assert that 12 O’Clock High came as close as any film in depicting what it was really like.

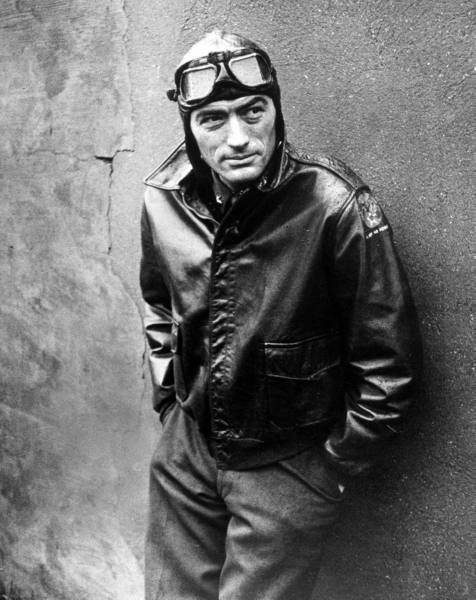

12 O’Clock High is also a star vehicle. Gregory Peck easily dominates his scenes, creating one of his best roles as General Frank Savage. The criticism that haunted him most of his career, that he had a somewhat immobile face and struggled with the deeper subtleties of acting, is overcome as the sensitive general who assumes the façade of the tough commander of the 918th Bomb Group after Keith Davenport (Gary Merrill) has been relieved due to stress and, as Savage deduces, “an over-identification with his men.” Although Gregory Peck was nominated Best Actor for this role, Dean Jagger, as the group adjutant, received the Best Supporting Actor Oscar. The picture also won for Best Sound.

12 O’Clock High is also a star vehicle. Gregory Peck easily dominates his scenes, creating one of his best roles as General Frank Savage. The criticism that haunted him most of his career, that he had a somewhat immobile face and struggled with the deeper subtleties of acting, is overcome as the sensitive general who assumes the façade of the tough commander of the 918th Bomb Group after Keith Davenport (Gary Merrill) has been relieved due to stress and, as Savage deduces, “an over-identification with his men.” Although Gregory Peck was nominated Best Actor for this role, Dean Jagger, as the group adjutant, received the Best Supporting Actor Oscar. The picture also won for Best Sound.

The long-lived Henry King, primarily with 20th Century-Fox, is one of Hollywood’s most reliable directors. He solidified the careers of both Tyrone Power, with at least eleven films, and Gregory Peck, with six during a ten-year span, from 12 O’Clock High to Beloved Infidel. King is assisted by one of the great cinematographers, Leon Shamroy, who received 18 nominations between 1938 and 1965, winning four Oscars. He was, in fact, nominated in 1949, not for 12 O’Clock High but for Prince of Foxes, coincidentally a Tyrone Power film.

The long-lived Henry King, primarily with 20th Century-Fox, is one of Hollywood’s most reliable directors. He solidified the careers of both Tyrone Power, with at least eleven films, and Gregory Peck, with six during a ten-year span, from 12 O’Clock High to Beloved Infidel. King is assisted by one of the great cinematographers, Leon Shamroy, who received 18 nominations between 1938 and 1965, winning four Oscars. He was, in fact, nominated in 1949, not for 12 O’Clock High but for Prince of Foxes, coincidentally a Tyrone Power film.

12 O’Clock High is told in flashback, and the transition from present to past is a study in ingenious film making, the way it used to be done. It’s 1949. A man (Jagger), dressed in civilian clothes, emerges from a London hat shop, having spent, as he tells the two clerks on the doorstep, “ . . . a most enjoyable one hour and forty minutes.” As he stops to admire his hat in the reflection of another store window, he notices a Robin Hood toby mug, which he immediately buys and tells the proprietor to “ . . . pack it carefully—very carefully.”

At Archbury station he disembarks from a train, and next is seen riding a bicycle through the countryside. He reaches a field. Alfred Newman’s English folk-song-tinted music is momentarily interrupted by more dramatic tones. As the lighter music returns, the man bends between the rails of a fence and walks through the tall grass, coming to what is obviously a deteriorated airstrip populated by cows. He walks further and hears a distant chorus of men’s voices: “Don’t Sit under the Apple Tree with Anyone Else But Me.” Still discernible among the weeds, stones form the word “Archbury.” There is a tower, other decaying buildings beyond. The man scrapes a grease spot with the toe of his shoe. He removes and cleans his glasses. He’s obviously thinking back to another time. . . .

At Archbury station he disembarks from a train, and next is seen riding a bicycle through the countryside. He reaches a field. Alfred Newman’s English folk-song-tinted music is momentarily interrupted by more dramatic tones. As the lighter music returns, the man bends between the rails of a fence and walks through the tall grass, coming to what is obviously a deteriorated airstrip populated by cows. He walks further and hears a distant chorus of men’s voices: “Don’t Sit under the Apple Tree with Anyone Else But Me.” Still discernible among the weeds, stones form the word “Archbury.” There is a tower, other decaying buildings beyond. The man scrapes a grease spot with the toe of his shoe. He removes and cleans his glasses. He’s obviously thinking back to another time. . . .

Now the magic! He hears engines revving, sees the grass swaying from an unexplained wind. The dramatic music hinted at before returns, now slightly ominous. The camera pans, again to the runway, now clean and used, then tilts skyward to B-17 bombers approaching from the distance. After several planes have landed, one belly crashes through several tents, spewing grass and dirt. Ambulances and a staff car dash to the aircraft. The story is underway.

Now the magic! He hears engines revving, sees the grass swaying from an unexplained wind. The dramatic music hinted at before returns, now slightly ominous. The camera pans, again to the runway, now clean and used, then tilts skyward to B-17 bombers approaching from the distance. After several planes have landed, one belly crashes through several tents, spewing grass and dirt. Ambulances and a staff car dash to the aircraft. The story is underway.

Among the officers from the staff car is Colonel Davenport, whose nervous, apprehensive glances, in a justified close-up, suggest the psychological problem that will cause his replacement. And the man we’ve been watching since the beginning, now in military coat and cap (Major Stovall), enters the crashed plane to retrieve the arm of the top turret gunner who parachuted over France in the hope of a French hospital.

Savage, before a congenial guy with easy advice, now sets out for the 918th. En route, his staff car stops alongside a country road. He lets himself out of the front seat and speaks casually to the driver: “Smoke, Ernie?” Dragging on his cigarette, he saunters around the back of the vehicle. Suddenly: “All right, sergeant!” The driver now jumps out and opens the rear door for the general. Savage has thus transformed himself into the hard ass who plans to revitalize that “hard luck” squadron.

At the base gate the staff car is waved through by the sentry (Kenneth Tobey in his one, brief appearance). A few yards beyond, the car stops. Savage gets out and walks back, suggesting to the guard that the car, for all the security he exercised, could have contained Hermann Göring. Savage sets him straight: “If you or any man on this post passes me up again without saluting, even if I’m a block away, you’ll wonder what fell on you.” And set, too, is Savage’s new tone!

At the base gate the staff car is waved through by the sentry (Kenneth Tobey in his one, brief appearance). A few yards beyond, the car stops. Savage gets out and walks back, suggesting to the guard that the car, for all the security he exercised, could have contained Hermann Göring. Savage sets him straight: “If you or any man on this post passes me up again without saluting, even if I’m a block away, you’ll wonder what fell on you.” And set, too, is Savage’s new tone!

Stovall, the base adjutant, soon befriends the new commander and conspires with him to delay paperwork for the airmen’s requests for transfers. Stovall sees through the tough guy veneer in one of the great revelations of the film: “Yeah, he’s pretty iron-tail. He’ll never feel things about the group the way Keith Davenport did. And nothing’s gonna start eating holes through him. He’s too tough for that. . . . You know something, Joe? The only difference between Frank Savage and Keith Davenport is that Savage is about that much taller.” He holds one forefinger a few inches above his thumb.

The rub, of course, is that Savage succumbs to Davenport’s problem, that “over-identification with his men.” He does become involved, he does care, and, in the end, the mental breakdown comes with stoic silence and blank stares—and escape into sleep.

It’s difficult to single out an example of Leon Shamroy’s masterful photography. In this film, his style, whether intentional or not, is in the many continuous shots, which are best observed, if unasthetically, in fast-forward on a DVD: in long stretches the framing remains the same, indicating the absence of cutting.

One early scene could be the ultimate antithesis of the rapid cutting which is practically standard in current movies. From a close-up of an intercom box, the scene begins with a pull-back to a long shot as Stovall enters to announce that Colonel Ben Gately (Hugh Marlowe), under arrest, has arrived. Gately enters. The two MPs leave. After keeping Gately waiting at attention, Savage, seated behind his desk, begins his long enumeration of the colonel’s transgressions. The camera moves in for a medium close-up of the two men as Savage stands up and sits on the edge of his desk, in Gately’s face. As Savage gets off desk and steps away, the camera pulls back slightly then returns to the earlier full shot as, first Gately, then Savage, leave the room.

One early scene could be the ultimate antithesis of the rapid cutting which is practically standard in current movies. From a close-up of an intercom box, the scene begins with a pull-back to a long shot as Stovall enters to announce that Colonel Ben Gately (Hugh Marlowe), under arrest, has arrived. Gately enters. The two MPs leave. After keeping Gately waiting at attention, Savage, seated behind his desk, begins his long enumeration of the colonel’s transgressions. The camera moves in for a medium close-up of the two men as Savage stands up and sits on the edge of his desk, in Gately’s face. As Savage gets off desk and steps away, the camera pulls back slightly then returns to the earlier full shot as, first Gately, then Savage, leave the room.

All shot with one camera, no cuts, five minutes and twenty seconds. How simple! But how effective! The dialogue, sharp and crisp, and Gregory Peck’s command of the scene, only heighten the impression of master movie making without fuss.

And the significance of the Robin Hood toby mug? Usually it sets on the mantle in the officers’ club, face to the wall; whenever there’s a mission the mug is turned face out. “Not again!” an officer mutters when he is confronted by the face.

With such an intense movie—it is, after all, the behind-the-scenes operation of a bomber squadron, with little screen combat—there has to be humor for relief, and humor there is. One running joke is the demotion, then immediate restoration of rank, of one Sergeant McIllhenny (Robert Arthur). At one point Savage instructs him to get chevrons with zippers “if we continue to have these ups and downs.”

After one mission, it’s discovered that many of the ground personnel were on board, including McIllhenny, Stovall and the group chaplain. “Your business is sin,” Savage tells the chaplain. “Hereafter you’ll confine your activities to that theater of operations.” When he tells Stovall that his combat days are over, the major replies, that as a machine gunner, “I think I got a piece of one.” Savage says, “Ours or theirs?” and walks off.

The film is in the past. So how to return to the present? After that last mission, after a concerned Colonel Davenport has removed the sleeping general’s boots and covered him with a blanket, Stovall leaves the Quonset hut, in the sky are an array of B-17s, which gradually dissolve to an empty sky. Stovall, in civilian clothes again, is still standing on the runway, now derelict once again. He bends back under the fence, mounts his bicycle and peddles off to a final swell in Newman’s music.