If it was murder, where’s the body?

What’s in a husband’s mind when he invites his wife’s lover to his home? An insightful conversation about the current banking crisis? To discuss a holiday for the three of them in the South of France? Or maybe there’s nothing in his mind and he needs to see a psychiatrist. Or maybe—just maybe—he’s planning to kill him? Or just pretend to kill him! Then again ——

And, as for the lover coming to call, what could he be thinking, perhaps putting himself at risk? What could be his motivations? Maybe to arrive at some mutual understanding, a financial agreement, a payoff? Or maybe he, too, needs to see a psychiatrist.

The first-time viewer of Sleuth (1972), unaware of what is to come, would naturally wonder why the two men are meeting. The first character to appear, arriving in a chic sports car at a sprawling manor, is thirty something, “neatly dressed in brand new country-gentleman’s clothing,” as his host would soon describe him. The visitor follows the sound of a man’s voice through a garden hedge maze.

An elevated, roving camera reveals a second man, clearly older, in the center of the maze, listening to his voice on a portable tape player—this was over thirty-five years ago!—then recording into it. He’s describing a crime and its solution by an eccentric fictional detective, with a “ponderous waistcoat,” created in an equally “ponderous” literary style by this, the presumed author.

An elevated, roving camera reveals a second man, clearly older, in the center of the maze, listening to his voice on a portable tape player—this was over thirty-five years ago!—then recording into it. He’s describing a crime and its solution by an eccentric fictional detective, with a “ponderous waistcoat,” created in an equally “ponderous” literary style by this, the presumed author.

And so it begins . . .

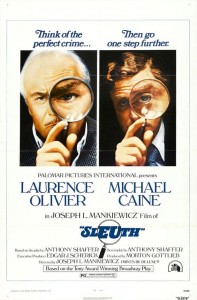

This is the kind of film which, sadly, is no longer being made—all that dialogue—which is the essence of Sleuth, from a play by Anthony Shaffer, twin brother of Peter, whose own play, Amadeus, was filmed in 1984. Each brother did the screenplay transfer of his work to film.

The movie admittedly feels like a transferred play. In a sense, the dialogue, though witty and totally captivating, isn’t always natural—too much perfect repartée, so quick that only a playwright, sitting behind a desk, would have time to think it up. For example (from Oliver): “ . . . my wife converses like a child of six and makes love like an extinct shellfish.”

The movie, at over two hours, is a tour de force for its two—and only—stars. Veteran Laurence Olivier was in the “twilight,” to use the cliché, of his career, although two years later he would be the villainous dentist in Marathon Man and, in 1981, have a key role as Lord Marchmain in the Granada/PBS television series “Brideshead Revisited.”

The movie, at over two hours, is a tour de force for its two—and only—stars. Veteran Laurence Olivier was in the “twilight,” to use the cliché, of his career, although two years later he would be the villainous dentist in Marathon Man and, in 1981, have a key role as Lord Marchmain in the Granada/PBS television series “Brideshead Revisited.”

Some of the visual “in” jokes include Olivier’s personal award plaques and pictures of Vivien Leigh, Agatha Christie and Leslie Howard; the painting of wife Marguerite, which the camera lingers over so often, is actually of Joanne Woodward. Once, he addresses his co-star as “Miss Rebecca,” presumably a reference to Hitchcock’s Rebecca, which the actor made in 1940 and in which he played the master of another English estate.

Much like Robin Williams, who can never suppress an impression, Olivier switches abruptly to various accents—German, Charlie Chan, American (gangster, cowboy), a little old lady, a “third character” in the movie (Inspector Doppler) and even enacts a two-person exchange. The tendency of Olivier to overact isn’t far away, particularly when, on the phone, he grimaces, inordinately it seems, over the “tragic” news of the fate of his mistress. In one cameo he even portrays an actor over-acting.

The co-star—he has second billing in deference to Olivier, but is his equal in acting ability and time on screen—is the then thirty-nine-year-old Michael Caine, who first attracted attention as a British officer fighting African warriors in Zulu (1964), later as a secret agent in The Ipcess File (1965) and as a small-time gangster in Get Carter (1971). Ten years after Sleuth, Caine would star as a washed up playwright in another play-based movie, Deathtrap. With similar plot twists, it’s a pale, dull imitation of the earlier cat-and-mouse mystery. He would, of course, win Oscars for Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and The Cider House Rules (1999).

The co-star—he has second billing in deference to Olivier, but is his equal in acting ability and time on screen—is the then thirty-nine-year-old Michael Caine, who first attracted attention as a British officer fighting African warriors in Zulu (1964), later as a secret agent in The Ipcess File (1965) and as a small-time gangster in Get Carter (1971). Ten years after Sleuth, Caine would star as a washed up playwright in another play-based movie, Deathtrap. With similar plot twists, it’s a pale, dull imitation of the earlier cat-and-mouse mystery. He would, of course, win Oscars for Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and The Cider House Rules (1999).

Caine, who never, in real life, attempts to conceal his Cockney origins, fits perfectly into the common man role here, freely using his native slang—“nick,” “git,” “nob” and “birds” for ladies. He is the opposite of the supposed wealth and sophistication of Olivier’s character.

Sleuth was Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s last creative effort, now only as director, since previously he was usually director and writer—A Letter to Three Wives, All About Eve and The Barefoot Contessa, among others.

Oswald Morris’ stylish cinematography is immediately obvious as the overhead camera follows Caine through the garden maze. Most fascinating is how the motionless camera continually returns to the photos and paintings on the wall, the automated figures and the Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Perhaps because the images are static—the camera rarely, if ever, dollies or zooms—the objects seem to assume a life of their own, silent observers of the drama taking place.

John Addison’s music, which in the main title sounds like something from Kabalevsky’s The Comedians, thereafter becomes quasi-baroque, with tinkling harpsichord—an idea gleaned from the Miss Marple/Margaret Rutherford films of ten years earlier? A passing tune on the keyboard suggests Larry Spiers’ “Put Your Little Foot Right Out.” The music does an about-face, turning sinister and otherwise “modern” on at least two occasions—when Caine, near the end of the film, reveals the truth behind his turn at game-playing and during the surprise fadeout.

And so, to continue—the beginning . . .

The plot of Sleuth is a simple one, as so often good plots are. An apparently unhappily married (the viewer is never certain) older man, Andrew Wyke (Olivier), aristocrat and mystery writer, whose fictional detective, Singen Lord Merridew, is world-famous, invites his wife’s lover, Milo Tindle (Caine), struggling owner of two hair-dressing salons, to an afternoon at his English estate. Wyke’s house is full of games, toys and automatons, one in particular, Jolly Jack Tarr, “the Jovial Sailor,” as Wyke calls him.

The plot of Sleuth is a simple one, as so often good plots are. An apparently unhappily married (the viewer is never certain) older man, Andrew Wyke (Olivier), aristocrat and mystery writer, whose fictional detective, Singen Lord Merridew, is world-famous, invites his wife’s lover, Milo Tindle (Caine), struggling owner of two hair-dressing salons, to an afternoon at his English estate. Wyke’s house is full of games, toys and automatons, one in particular, Jolly Jack Tarr, “the Jovial Sailor,” as Wyke calls him.

With one of the most memorable lines in the film, Wyke, after earlier innuendos, says to Tindle, “I understand you want to marry my wife.” Wyke establishes that he’d not be that unhappy to lose Marguerite, and implies that Tindle doesn’t know how “intolerably tiresome, vain, spendthrift, self-indulgent and generally bloody crafty she really is.” He suggests that, if the lover is to support his wife in the manner to which she has become accustomed since her marriage, he’ll need some money.

Wyke outlines how Tindle is to steal his jewels, complete with a convincing modus operandi and an unconventional disguise, that of a clown! When the would-be burglar slips clamorously from a ladder, Wyke shouts out the window, “They couldn’t have made more noise on D-Day!”

Wyke outlines how Tindle is to steal his jewels, complete with a convincing modus operandi and an unconventional disguise, that of a clown! When the would-be burglar slips clamorously from a ladder, Wyke shouts out the window, “They couldn’t have made more noise on D-Day!”

Wyke’s childlike nature—his obsession with games and his existence in a fantasy world—is partially shared by Tindle, who reacts with childish delight in donning his clown outfit and in the way he sits down on the floor to admire the jewels he’s extracted from the safe.

Wyke’s childlike nature—his obsession with games and his existence in a fantasy world—is partially shared by Tindle, who reacts with childish delight in donning his clown outfit and in the way he sits down on the floor to admire the jewels he’s extracted from the safe.

After Tindle has planted his big-clown footprints in the flower bed, broken a two-story window and Wyke has dynamited his own safe, it turns out that all the machinations were a setup—a setup for Tindle’s murder or, rather, Wyke’s legitimate killing of his wife’s lover as an intruder. And so, Wyke shoots the “intruder,” with clown mask in place, and Tindle collapses down the staircase, apparently dead.

Next scene. A few nights later, Wyke is merrily preparing a supper of caviar and lemon and wine, to the accompaniment of Cole Porter tunes, most notably “Anything Goes,” when the front door, then the back door servant’s bell jangles on the kitchen wall. At the door is an Inspector Doppler from the Wiltshire County Constabulary, come to investigate the strange disappearance of a Mr. Milo Tindle. Wyke, ever the gentleman-host, invites the policeman in, shows him about the house and introduces him to his pet obsessions—his games, Jolly Jack Tar and the eminent Singen Lord Merridew, of whom Doppler has never heard. He later jokingly refers to the detective as “Merridick.” Wyke, indignant, corrects him: “Merridew! Merridew!”

Next scene. A few nights later, Wyke is merrily preparing a supper of caviar and lemon and wine, to the accompaniment of Cole Porter tunes, most notably “Anything Goes,” when the front door, then the back door servant’s bell jangles on the kitchen wall. At the door is an Inspector Doppler from the Wiltshire County Constabulary, come to investigate the strange disappearance of a Mr. Milo Tindle. Wyke, ever the gentleman-host, invites the policeman in, shows him about the house and introduces him to his pet obsessions—his games, Jolly Jack Tar and the eminent Singen Lord Merridew, of whom Doppler has never heard. He later jokingly refers to the detective as “Merridick.” Wyke, indignant, corrects him: “Merridew! Merridew!”

Balding and with a mustache, the inspector is somewhat over-weight, stoop-shouldered, with a duck-waddle and thick speech. Though quite a contrast to Wyke, who, even at this late hour is in dinner jacket and ascot, the disheveled Doppler quickly gains the upper hand with his keen observations and mounting bits of evidence against his host.

After accepting a drink, which, strangely, on-duty policemen are supposed to decline, Doppler refers to shots heard by a passer-by several nights ago and produces Wyke’s note inviting Tindle to his estate. Doppler finds a mound of earth in the yard, bullet holes in the wall, blood on the banister and Tindle’s clothes in the closet.

As the evidence mounts, Wyke admits that, yes, Tindle was there, that, in fact, he, Wyke, had staged a fake murder. It was only a game, and Tindle had “lurched off” quite alive. The first two shots—at a Swansea puzzle jar and a photo of his wife—were real, to set up the trick, the last, a blank, to carry it out. Finding Tindle’s clothes in a closet, Doppler shouts, “Did Mr. Tindle ‘lurch off’ naked?!”

The inspector is unconvinced and says he will have to take Wyke to police headquarters. Wyke protests, then races through the house to escape. Doppler pins him down. Wyke is desperate, clearly frightened. The inspector casually says that “Doppler” is almost an anagram for the German word “doppel,” which means double, and begins removing his face mask, wig, false nose, mouth inserts and waist padding. It’s Tindle.

Tindle confides that the experience of being “shot” was something he’d never forget, to know, he says, that “ . . . my coat sleeve button, the banister, the nail on my forefinger were absolutely the last things I was going to see—ever. Then I heard the sound of my own death. Now that changes you, Andrew, believe me.” Wyke backhandedly compliments Tindle’s disguise, saying he loved his Inspector Doppler, but that he was never fooled for a moment. Tindle argues that his fellow game-player’s panic appeared genuine enough.

To get even, Tindle says he has, in fact, murdered—really murdered, this time—Wyke’s mistress, Thea—strangled her—and that Wyke should call her roommate to confirm it. Wyke does so and hears the ghastly news and that the police are on their way. To add suspense to this game, Tindle says four items of evidence incriminating Wyke are scattered about the room, their location concealed in riddles which the hair-dresser provides. Wyke has fifteen minutes before the police arrive.

Wyke rushes about. He forgets that Tindle said the clues were in that one room and checks in the billiard room, and the playwright himself forgets what he wrote, for one of the items is in the cellar. Although Wyke makes false assumptions and checks in unfruitful places, and is in genuine panic, there are moments when he’s thoroughly enthralled. As Tindle observes, though his life may depend on it, Wyke is excited by playing yet another game.

Wyke rushes about. He forgets that Tindle said the clues were in that one room and checks in the billiard room, and the playwright himself forgets what he wrote, for one of the items is in the cellar. Although Wyke makes false assumptions and checks in unfruitful places, and is in genuine panic, there are moments when he’s thoroughly enthralled. As Tindle observes, though his life may depend on it, Wyke is excited by playing yet another game.

Wyke finds all the clues, but the police never arrive. It’s another trick, now on Tindle’s part! The blood, the clothes, the mound of earth were all planted while Wyke was away and Thea’s roommate was a willing accomplice.

There is yet another twist in the plot—not a trick but a false presumption, one that proves unfortunate for both men, a twist not to be divulged here, however—for those who haven’t seen the film. Ah, come on!—after revealing ninety-five per cent of the movie? ——

There was much secrecy in the initial release of the film and a deception on the part of the producers, similar to Alfred Hitchcock’s refusal to admit movie-goers after Psycho had begun. In Sleuth, three other actors’ names listed in the opening credits—John Matthews, Eve Channing and Teddy Martin—do not appear in the film. They do not appear because they do not exist! Olivier and Caine have the movie to themselves, after all.

Which brings up perhaps the most amazing feature of the film—Michael Caine’s disguise as Inspector Doppler. On first viewing, it’s possible to be completely deceived, accepting that “Alec Cawthorne as Inspector Doppler,” as listed in the credits, is a new, unknown actor. English obviously, initiating a career late in life, perhaps. On subsequent viewings, it remains—what was that term at the beginning?—a tour de force for the actor.

I liked your review, but you MUST correct one of your first salvos! It’s a PENDULOUS Waistcoat, swinging like a large PENDULUM on the man’s rotund body!!

Watched this film as a kid in the late 70’s, think it was shown on Christmas Eve one year, was totally taken in by it to the very end. Two brilliant actors with a fantastic script…loved the cinematography and the way the camera would zoom in on the various automata and figurines. Will watch it again this Christmas!

this is really bugging me. Obviously Wyke thought Tindle was dead after firing what probably really was a blank. He even checked Tindle’s pulse. We saw the car hidden in some bushes later. SO: what did Wyke do with the body? Tindle had to have awakened, got around to Wyke’s paramour’s house to set up his counter-scheme and make it back…curiously all without his car. A smaller issue is what did Tindle plan to accomplish by having the police arrive? By then, it seems, he would have left the house successfully with Mrs. Wyke’s fur and had no murder to accuse Wyke of. Feel free to email me for what I seem to have missed.