A laugh tops every thrilling moment!

A laugh tops every thrilling moment!

1934 is ancient history to many people. To casual admirers of the films of Hollywood’s Golden Age, the year, perhaps, is a blurry recollection of the first of those old movies made available to TV; to devotees “in the know,” 1934 suggests things to come—and the great, milestone years just over the horizon. A dramatic upswing the very next year, 1935, would, in fact, yield at least six significant pictures, while ’34 would bequeath a few less, perhaps three.

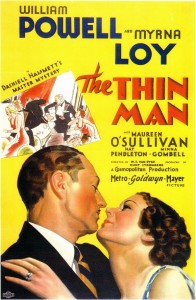

Well, maybe a fourth, The Thin Man, with William Powell and Myrna Loy.

1934 was the third year in which Best Picture nominations had increased from the traditional five—eight in 1931-32, ten in 1932-33 and, now, in 1934, twelve. The number would thus fluctuate until 1944, when the selection would revert to five. (Now, for the 2009 films, there will again be ten nominations. According to Academy president Sid Ganis, this is “to allow Academy voters to . . . include some of the fantastic movies that often . . . have been squeezed out of the race for the top prize.” With fewer great, even good movies being made in recent years, the change seems unwarranted. Whatever.)

Some major changes did occur in 1934. For the first time since the initial awards in 1927-28, the eligibility period for Oscar nominations would no longer be the so-called “seasonal” period from August 1 to July 31 but the calendar year. Apparently noticed as an important ingredient in the “screen” of things, so to speak, music was belatedly recognized, for the first time, with Best Song and Best Score Oscars. Sound had, after all, arrived some six years earlier! There was also a new category, Film Editing.

Some major changes did occur in 1934. For the first time since the initial awards in 1927-28, the eligibility period for Oscar nominations would no longer be the so-called “seasonal” period from August 1 to July 31 but the calendar year. Apparently noticed as an important ingredient in the “screen” of things, so to speak, music was belatedly recognized, for the first time, with Best Song and Best Score Oscars. Sound had, after all, arrived some six years earlier! There was also a new category, Film Editing.

In 1934 occurred one of the first incidents, certainly the most volatile so far, of strife over Academy protocol. Not only eligible Academy voters but critics and ordinary citizens protested, through letters, telegrams and editorials, the omission from the Best Actress nominations of Bette Davis for Of Human Bondage and Loy for The Thin Man. As a pacifier,“write-in” ballots were allowed. Surprisingly, no unnominated star won, Davis, Loy nor any one else. It was a clean sweep for It Happened One Night, in the top five categories—Picture, Actor (Clark Gable), Actress (Claudette Colbert), Director (Frank Capra) and Adapted Screenplay (Robert Riskin). There would be no supporting actor Oscars until 1936.

The overnight success and Oscar wins of It Happened One Night, that “little” picture which M-G-M had famously assigned to Gable as punishment for refusing an assignment, was as much of a fluke as The Thin Man. Man began life as a “B” movie “quickie,” filmed in around twelve days by W. S. Van Dyke, known as “One-Take Woody,” at a cost, even by 1934 standards, of a paltry $231,000.

The overnight success and Oscar wins of It Happened One Night, that “little” picture which M-G-M had famously assigned to Gable as punishment for refusing an assignment, was as much of a fluke as The Thin Man. Man began life as a “B” movie “quickie,” filmed in around twelve days by W. S. Van Dyke, known as “One-Take Woody,” at a cost, even by 1934 standards, of a paltry $231,000.

Frequently in the 1930s and ’40s even ordinary films—whatever they are—were not without impressive credentials, a byproduct of the studio system. Some of those old, creaky “B” horror films, say, from Universal, might boast a great German director or a pioneering cameraman. The Thin Man is no ordinary, certainly no “B,” film. Besides the dash of Van Dyke, who also directed Tarzan the Ape Man (1932), Johnny Weissmuller’s début as the jungle hero, the film is photographed by none other than James Wong Howe (Kings Row, The Rose Tattoo, Hud), with art direction by Cedric Gibbons (The Merry Widow, Little Women, An American in Paris).

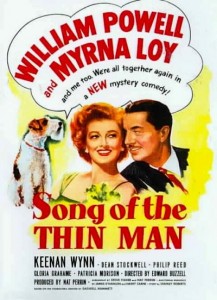

The movie is based on the novel by Dashiell Hammett, where the “thin man” is actually the first murder victim, Clyde Wynant (Edward Ellis), but Powell, who is tall and thin, quickly acquired the label, so the nickname remained throughout the five sequels, which would end in 1947 with Song of the Thin Man. All except the last two are directed by Van Dyke, who died in 1943. Coincidentally, earlier in 1934, he had directed the first teaming of Powell and Loy in Manhattan Melodrama with Gable.

The pair play Nick and Nora Charles, amateur husband-and-wife sleuths. It isn’t the sleuthing that best characterizes them, though that’s part of the fun, but the portrayal, perhaps for the first time in the movies, of a carefree, sophisticated and happily married couple, who openly show affection, exchange sexual innuendos and delight in physical humor. Simply put, they enjoy life and . . . drink a lot, especially Nick.

In fact, in The Thin Man, Nick is first seen at a bar, demonstrating the proper way to shake drinks. “Always have rhythm in your shaking,” he says. “Now a Manhattan you shake to fox-trot time, a Bronx to two-step time. A dry martini you always shake to waltz time.” Nora enters, with the third member of the family, Asta, the wire-haired fox terrier, tugging on his leash. After a disquieting pratfall, Nora wants to know how many martinis her husband has had. Six. As the waiter brings her a drink, she asks for five more, to be lined up on the table in front of Nick. She’ll prove she’s his equal—in drinking as well as in everything else. As it turns out—next scene—she’s in bed with a hangover and an ice pack.

In fact, in The Thin Man, Nick is first seen at a bar, demonstrating the proper way to shake drinks. “Always have rhythm in your shaking,” he says. “Now a Manhattan you shake to fox-trot time, a Bronx to two-step time. A dry martini you always shake to waltz time.” Nora enters, with the third member of the family, Asta, the wire-haired fox terrier, tugging on his leash. After a disquieting pratfall, Nora wants to know how many martinis her husband has had. Six. As the waiter brings her a drink, she asks for five more, to be lined up on the table in front of Nick. She’ll prove she’s his equal—in drinking as well as in everything else. As it turns out—next scene—she’s in bed with a hangover and an ice pack.

“What hit me?” she asks.

“That last martini,” Nick replies.

Cheeky references to drink abound. Two involve newspaper reporters at the lengthy, chaotic Christmas party, which has the hectic pace and overlapping dialogue of Howard Hawks’ His Girl Friday, six years later. When asked which case Nick is working on, Nora snaps, “A case of scotch.” One reporter asks Nick why he’s in town. “My wife’s on a bender. I’m trying to sober her up.” In another scene, a reporter asks Nick about the investigation. “It’s putting me way behind in my drinking.”

There is some slick taunting of the censors. After a man (Edward Brophy) has entered their bedroom and fired a gun and the police are searching the place, Nora shouts, “What’s that man doing in my drawers?!” In the same scene, Lieutenant Guild (Nat Pendleton) asks, “Ever heard of the Sullivan Act?” Whereupon she replies, “Oh, that’s all right. We’re married.” In a later scene, while Nick is lounging on a sofa and shooting at balloons on the Christmas tree with a pop gun, Nora says, “I read where you were shot five times in the tabloids.” (Correctly, “I read in the tabloids where you were shot five times.”) “It’s not true,” Nick replies. “He didn’t come anywhere near my tabloids.”

Despite the banter, the double entendre and the drinking, it’s easy to see that the couple are deeply in love. In a scene at the front door, Nick is leaving to take Asta for a walk and inspect Wynant’s office. Nora knows danger is involved. When Nick, tipsy as usual, assures her he’s prepared for any eventuality, she says, “Take care of yourself.”

“Why, sure I will,” Nick replies.

“Don’t say it like that. Say it as if you mean it.”

“Well, I do believe the little woman cares.”

“I don’t care! It’s just that I’m used to you, that’s all.”

An apology for putting off discussing Myrna Loy, who was, after all, Franklin Roosevelt’s favorite actress, but William Powell is the heart of the movie, one of the most debonair men in Hollywood, as at ease in a tuxedo in a drawing room as Errol Flynn is in an historical costume on the deck of a ship.

Powell’s career began in the silent era—with, among others, Sherlock Holmes (1922) and Beau Geste (1926), though not as the title characters. It was in the detective genre, however, where he found his niche. Numerous actors have played S. S. Van Dine’s sleuth Philo Vance—Warren William, Basil Rathbone, Alan Curtis, William Wright, even Wilfrid Hyde-White in a British production—but Powell adds to the character his inimitable sophistication, graceful movement and erudite diction. The Canary Murder Case and The Greene Murder Case (both 1929) and The Benson Murder Case (1930) are now dated, but the most absorbing is The Kennel Murder Case (1933), due largely to Michael Curtiz’ tight direction. The plot centers around that old cliché—well done here—of a murder victim (Robert Barrat) found in a locked room.

Powell’s career began in the silent era—with, among others, Sherlock Holmes (1922) and Beau Geste (1926), though not as the title characters. It was in the detective genre, however, where he found his niche. Numerous actors have played S. S. Van Dine’s sleuth Philo Vance—Warren William, Basil Rathbone, Alan Curtis, William Wright, even Wilfrid Hyde-White in a British production—but Powell adds to the character his inimitable sophistication, graceful movement and erudite diction. The Canary Murder Case and The Greene Murder Case (both 1929) and The Benson Murder Case (1930) are now dated, but the most absorbing is The Kennel Murder Case (1933), due largely to Michael Curtiz’ tight direction. The plot centers around that old cliché—well done here—of a murder victim (Robert Barrat) found in a locked room.

Apart from his detective roles, Powell is remembered for The Great Ziegfeld (1930), My Man Godfrey (1936) and Life with Father (1947), three quite diverse films. He was nominated Best Actor for the latter two and for the initial Thin Man, winning only for Life with Father, starring opposite Irene Dunne, Edmund Gwenn and a 15-year-old Elizabeth Taylor. He retired after his last film, Mister Roberts (1955), and lived another twenty-seven years, dying at the age of 91.

Myrna Loy, the perfect foil for Powell, began her career, like Powell, in the silent days. She appeared in John Barrymore’s Don Juan (1926), and was often cast in oriental roles, most famously as Fu’s (Boris Karloff) evil daughter in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932).

Myrna Loy, the perfect foil for Powell, began her career, like Powell, in the silent days. She appeared in John Barrymore’s Don Juan (1926), and was often cast in oriental roles, most famously as Fu’s (Boris Karloff) evil daughter in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932).

Her popularity peaked in the late ’40s with The Best Years of Our Lives with Fredric March, The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer with Cary Grant, The Red Pony with Robert Mitchum and the original—and best—Cheaper by the Dozen (1950) with Clifton Webb. She delivers one of her best-remembered lines in Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, again opposite Grant. To a painter she describes the subtle colors she requires in her new home: “I want it to be a soft green, not as blue-green as a robin’s egg, but not as yellow-green as daffodil buds.”

This “Queen of Hollywood,” as she was sometimes called, was never nominated for an Oscar, though there was the write-in incident in 1934. As compensation for being overlooked, as the Academy often does, she was given a lifetime achievement Oscar in 1991, two years before her death.

Composer William Axt is listed in the short main title, but there is hardly any original score. Although not an Erich Wolfgang Korngold type film, Frederick Hollander or Adolph Deutsch would have felt quite at home here; better yet, Roy Webb, one of the most underrated Hollywood composers, would have added a sparkle equal to the screen (witness Top Secret Affair, 1957). The most memorable music is source music during Nick and Nora’s Christmas party, including Christmas songs and Powell singing a cappella. In the fadeout, “California, Here I Come” does come from the orchestral soundtrack, and the subtle sexual inference would be perfected—and far less subtle—by Alfred Hitchcock in the fadeout of North by Northwest (1959).

Composer William Axt is listed in the short main title, but there is hardly any original score. Although not an Erich Wolfgang Korngold type film, Frederick Hollander or Adolph Deutsch would have felt quite at home here; better yet, Roy Webb, one of the most underrated Hollywood composers, would have added a sparkle equal to the screen (witness Top Secret Affair, 1957). The most memorable music is source music during Nick and Nora’s Christmas party, including Christmas songs and Powell singing a cappella. In the fadeout, “California, Here I Come” does come from the orchestral soundtrack, and the subtle sexual inference would be perfected—and far less subtle—by Alfred Hitchcock in the fadeout of North by Northwest (1959).

In the fashion of the Agatha Christie/Poirot mysteries, there is a protracted dénouement at the end of each Thin Man film. In the 1934 original, ten or twelve suspects are gathered—brought in, if necessary, by the police. Nick Charles elegantly presides over the lavish dinner. Several times during his summation of the case he addresses various individuals as though in an accusation, prompting startled looks among the guests and heart skips from first-time viewers. The murderer is never treated as a suspect during the movie, in fact seems to move outside the turmoil of the plot, yet he is conspicuously in the foreground, so obvious, perhaps, that he’s easily disregarded.

Years before film noir historically started, and was for so many years the vogue, The Thin Man anticipates that art of exaggerated lighting and eccentric shadows, thanks largely to Howe and Gibbons. As in all Thin Man installments, Nick’s search through a dark and deserted building gives ample excuse for a flashlight circle amid the gloom.

The subsequent Thin Man films assume new story lines and settings, but they never capture the spirit of the original, though the second, After the Thin Man (1936), with the Charles family in San Francisco, comes close. The then relatively unknown James Stewart has a crucial role. In Another Thin Man (1939), Nick and Nora investigate murder at a Long Island estate. By now there’s an addition to the cast, baby, Nick, Jr., who appears in the ensuing films.

The subsequent Thin Man films assume new story lines and settings, but they never capture the spirit of the original, though the second, After the Thin Man (1936), with the Charles family in San Francisco, comes close. The then relatively unknown James Stewart has a crucial role. In Another Thin Man (1939), Nick and Nora investigate murder at a Long Island estate. By now there’s an addition to the cast, baby, Nick, Jr., who appears in the ensuing films.

Donna Reed, appearing in her second movie, is merely an attractive ornament in Shadow of the Thin Man (1941), about race track intrigue. In The Thin Man Goes Home (1944), Nick visits his parents, delightfully played by Lucile Watson and Harry Davenport, but even in quiet suburbia murder is afoot. The forever nervous Donald Meek is the store proprietor who sells a certain painting to Nora.

The last film, Song of the Thin Man (1947), though the weakest of the six, is partially saved by the excellent supporting players—Keenan Wynn, Gloria Graham and Dean Stockwell, as 11-year-old Nick, Jr.

The last film, Song of the Thin Man (1947), though the weakest of the six, is partially saved by the excellent supporting players—Keenan Wynn, Gloria Graham and Dean Stockwell, as 11-year-old Nick, Jr.

After the thirteen years since 1934, it’s sad to see, in 1947, the age that shows in the faces of the principal stars, though William Powell is as agile and debonair as ever and Myrna Loy is his charming equal. They were one of the great romantic couples of Hollywood, united in eight films besides the Thin Man series. The 1934 Thin Man inspired a new kind of sophisticated film, a new genre, a combination of mystery, comedy and romance that is still with us, if only, for the most part, in pale and anemic imitations.

2 thoughts to “Remembering 1934 and The Thin Man”