There is nothing in the dark that isn’t there in the light. Except fear.

Why was a remake thought necessary?

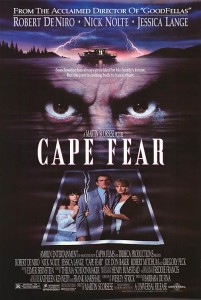

Cape Fear is not among Martin Scorsese’s better films. Watching the 1991 remake gives the persistent impression of being crucially unnecessary—unnecessarily violent and unnecessarily depressing, and full of unattractive people. Bernard Herrmann’s score, lifted essentially in tact from the 1962 original, is a saving grace.

Here I am, crabby old me, prepared to make the case that the remake was, indeed, unnecessary. I’ve come, now, in a self-imposed debate with myself—a predictable win, you suspect?—that here is further evidence that the old movies of the ’30s and ’40 and, yes, even into the ’50s, maybe a smidgen from the ’60s, are superior, on the average, to those made during the ’70s through the present time.

Here I am, crabby old me, prepared to make the case that the remake was, indeed, unnecessary. I’ve come, now, in a self-imposed debate with myself—a predictable win, you suspect?—that here is further evidence that the old movies of the ’30s and ’40 and, yes, even into the ’50s, maybe a smidgen from the ’60s, are superior, on the average, to those made during the ’70s through the present time.

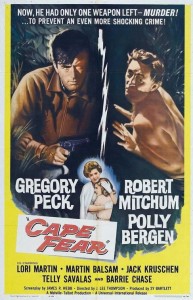

J. Lee Thompson, perhaps best remembered for The Guns of Navarone (1961), directed the original Cape Fear with Gregory Peck, Robert Mitchum, Polly Bergen, Lori Martin, Martin Balsam, Jack Kruschen and Telly Savalas. Scorsese, deservedly more famous for GoodFellas and Taxi Driver, filled the same or stand-in roles with Nick Nolte, Robert De Niro, Jessica Lange, Juliette Lewis, Fred Dalton Thompson and Joe Don Baker.

The source material is The Executioners by John D. MacDonald, who also created detective Travis McGee in a series of crime novels. There’re other “MacDonald” mystery and crime writers with whom John shouldn’t be confused: Ross, the American who created gumshoe Lew Archer in another series; Phillip, a Brit, who penned a personal favorite, The List of Adrian Messenger, one in a series about that author’s detective creation, Anthony Gethryn; and another American, Patricia, the only one living of these four, who ties family dramas to her crimes stories.

In the Cape Fear remake, Nolte (Peck in the original) is Sam Bowden, the lawyer sought out by Max Cady (De Niro/Mitchum) for sending him to prison some years earlier. Jessica Lange, who immediately emits an earthy sexuality, is a sharp contrast to Bergen’s pure wife reaction to Cady’s embrace. Lange even makes an impromptu speech, somehow unconvincing, about how she is attracted to Cady, an effort to spare her daughter.

In the Cape Fear remake, Nolte (Peck in the original) is Sam Bowden, the lawyer sought out by Max Cady (De Niro/Mitchum) for sending him to prison some years earlier. Jessica Lange, who immediately emits an earthy sexuality, is a sharp contrast to Bergen’s pure wife reaction to Cady’s embrace. Lange even makes an impromptu speech, somehow unconvincing, about how she is attracted to Cady, an effort to spare her daughter.

Nancy, the 15-year-old daughter, an innocent child of the ‘60s as played by Martin, now becomes Danielle (Lewis), a nearly unmanageable teenager of the ‘90s. She at first doesn’t believe all the bad things said about Cady. She is fascinated by his voice on the phone. Later, in an over-long scene in which he poses as a drama teacher, she lets him kiss her and insert his thumb in her mouth—not once but twice—an obvious phallic symbol of the rape he has in mind for her.

The obvious difference between the two versions of Cape Fear, as some critics have noted, is that, as already suggested, the victimized family in 1991 is no longer nicey-nice and all-American, but spoiled, tainted and rich. Sam and his wife have been in therapy over what is a sometimes violent marriage. The two come to blows—both physical and verbal—over his infidelities. As a lawyer, Sam is guilty of withholding critical evidence in Cady’s long ago case.

Scorsese retains many of the scenes and ideas of the original, including the poisoning of the family dog, the lawyer’s attempt to pay off his harasser, later setting three thugs on Cady and, in the climax, a deceptive airplane departure. Sam hopes the stalker will attack his presumably unprotected wife and daughter at the houseboat on the Cape Fear River, North Carolina. In the remake, the private detective (Joe Don Baker) is murdered by Cady, who penetrates the tight security of the house disguised as the housekeeper, an idea at least as old as the Sherlock Holmes movie, The Scarlet Claw of 1944.

The new Sam Bowden’s sexual indiscretions provides Scorsese with a “wonderful” opportunity for more gore and violence—the horrific disfigurement of Sam’s on-the-side girlfriend (Illeana Douglas), who refuses to bring charges and leaves town, having been informed by Cady that this treatment is only a “sample.”

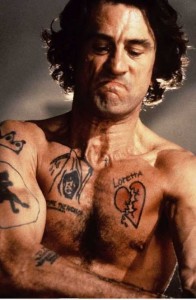

Mitchum’s occasional quoting of scripture is expanded for De Niro, who takes the fanaticism further: his arms and torso are tattooed with Biblical symbols and quotes. In the final analysis, the obvious has to be asked: Despite De Niro’s tattoos and his extroverted, violent, over-the-top performance, isn’t Robert Mitchum, because of his hulking stature, indolent voice and under acting, the more menacing?

Mitchum’s occasional quoting of scripture is expanded for De Niro, who takes the fanaticism further: his arms and torso are tattooed with Biblical symbols and quotes. In the final analysis, the obvious has to be asked: Despite De Niro’s tattoos and his extroverted, violent, over-the-top performance, isn’t Robert Mitchum, because of his hulking stature, indolent voice and under acting, the more menacing?

In addition to typically giving family members minor roles, Scorsese assigns cameo parts to some of the 1962 alumni—Peck (in his last appearance in a theatrical film), Mitchum and Martin Balsam who played a police chief.

In addition to typically giving family members minor roles, Scorsese assigns cameo parts to some of the 1962 alumni—Peck (in his last appearance in a theatrical film), Mitchum and Martin Balsam who played a police chief.

The film’s climax of unrelenting terror goes beyond the necessary in gore, blood and violence.. De Niro puts the daughter in the hold of the houseboat just long enough for her to hide a squeeze-bottle of lighter fluid under her blouse. A little later when Nolte is sufficiently unconscious and De Niro has the two women before him, he lights a cigar, whereupon Lewis squirts the lighter fluid at him. Head and shoulders in flames, he staggers blindly about the boat and falls overboard.

End of story? Nice if it would have been; it would have done the picture a favor and reduced extending the pain of an already overblown endeavor. But, no, in the worst cliché of the Night on Elm Street slasher movies, De Niro climbs back on board by way of the dangling anchor cable, which he had cut earlier, and the violence and terror resume for what seems like ten more minutes. This devotion to violence, after an end of sorts had already been reached, is the film’s most conspicuous weakness.

What is missing, in a word, is restraint. Subtlety, a toning down of the film’s extremes, obviously wasn’t Scorsese’s inclination, or, perhaps, in his nature. There could have been, say, a gradual darkening of the screen, an increase in tempo as the terror grows, the way Alfred Hitchcock might have done, but there are no variances, no crescendo, only an insistent, unrelenting fortissimo. (Or perhaps Scorsese should be respected for not copying Hitch.)

What is missing, in a word, is restraint. Subtlety, a toning down of the film’s extremes, obviously wasn’t Scorsese’s inclination, or, perhaps, in his nature. There could have been, say, a gradual darkening of the screen, an increase in tempo as the terror grows, the way Alfred Hitchcock might have done, but there are no variances, no crescendo, only an insistent, unrelenting fortissimo. (Or perhaps Scorsese should be respected for not copying Hitch.)

There is, however, an Hitchcockian touch at the beginning of the film—thunder clouds hover as De Niro leaves prison—that recalls Hitch’s Shadow of a Doubt and the train smoke that blackens sky and screen as Joseph Cotton arrives in Santa Rosa. The symbolism in both films is obvious: evil is at hand.

Not to worry. There’s still Herrmann’s magnificent, totally appropriate and compelling music. The most redeeming feature in this remake is the score. No mere “score,” this! The credits indicate “adapted, arranged and conducted by Elmer Bernstein,” with “orchestrations by” Bernstein’s daughter, Emilie. Huh? Why would Herrmann’s music, of all film composers’, need an orchestrator? Herrmann did his own. Perhaps, more accurately, Emilie’s actual job was as a reconstructor of the score, if, say, no physical manuscripts existed. In any case, the music remains convincingly vintage Herrmann.

When Herrmann’s music leaps—or creeps, as the case may be—it energizes the film, making it, somehow, better than it is. To the so-called “quiet” moments, the music adds a menacing undertow, and to the violent ones—and there are plenty—a full-fledged terror. After the music of the main title—accompanied by superb visuals—has moaned and groaned, more often snarled and raged, mostly in the brass and with typical Herrmannian two- and four-note motifs, all that follows from the actors, photographer Freddie Francis and director Scorsese is anticlimactic.

Like an enduring overture to a long-forgotten opera, the main title encapsulates the drama of the 1991 Cape Fear and becomes, along with the music to follow, the best part of a damaged whole. For a more rewarding experience, watch the 1962 original, or, if you accidentally, unavoidably stumble upon the remake, stay with it—if only to hear it!

Couldn’t agree with you more! I could not believe the ending of the remake and said out loud, “Who is he? Freddie Kruger???” I actually said that. This was the first one I saw. I didn’t know there was a ’62 version. I saw that one yesterday and wondered why this absolutely fabulous film was remade! I thought, “They should’ve just rereleased the old one.” I actually lost some respect for De Niro after I watched the remake.

I thought it was terrific.

The point is if Sam didn’t bury the evidence and break the law maybe Cady wouldn’t have turned into a religious fanatic. 14 years in prison and being abused in horrific ways will most likely turn you insane

I think this review is more detailed. No offence here but the author clearly didn’t like the film and does a review which doesn’t really to the film service

I think this review is more detailed: http://www.cutprintfilm.com/features/cape-fear/

No offence here but the author clearly didn’t like the film and doesn’t really do it service. Though I suppose it depends what you’re looking for, just a neat, well made and simpler film or a hyper film with more complexities.

I don’t see any mention of Nietzsche in your article. Scorsese’s Fear, whether it’s liked or not, to me creates a much more complex and dense film compared to the original. There’s less of the Hollywood good and evil (last scene is cartoony I know).

The remake adds more questionable morality, the family are rather unlikeable and look down at Cady because they think they’re better. Sam is a cheating husband and bad father. He, as an upper class lawyer, looks down at Cady but he is no saint either.

There’s a great article examining the remake philosophically which I don’t think you did:

https://philosophynow.org/issues/82/Cape_Fear