Wish to discover a delightful movie? Then, for an enjoyable custard of delight, sample A Touch of Larceny.

“The trouble with you, Easton, is you have no principles.”

—George Sanders to James Mason

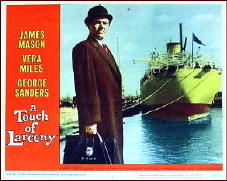

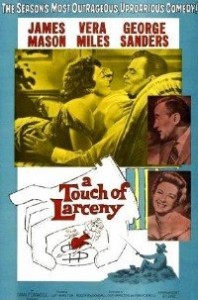

A Touch of Larceny is an extremely—extremely—obscure little film. This 1959 confection of droll British humor demonstrates, above all, the comic skills of the usually villainous James Mason. He is supported in this delightful soufflé by both the lovely Vera Miles, twenty years his junior—never a credibility problem—and the nasty George Sanders in a typically unsympathetic role. Mason steals the show, dominating the screen with an engaging performance. He is so good, so relaxed, so comfortable with his character that this may be his finest comedy.

He triumphs, too, in another area rarely regarded as his territory, that of a romantic lead. There is a playful chemistry between Mason and Miles, as, for starters, when she’s on his little sailboat and he outlines a money-making scheme. They’ve already been talking in casual double-entendre, the sea weather vis-à-vis their relationship, and when she says, “Is that a squall coming out way?,” he smiles impishly and says, “I shouldn’t be a bit surprised.”

The admirable cast of familiar British supporting players includes Harry Andrews (Captain Graham), Percy Herbert (Bert a port warden) and Duncan Lamont (an investigator ), plus Oliver Johnston, William Kendall and Robert Flemyng.

While a leisurely pace can be fatal to a film, especially in a comedy, the master of leisure, Guy Hamilton, directs up a storm . . . well, at least stirs a pleasant breeze, which provides just enough momentum to keep things interesting. The more accelerated tempo of, say, a screwball or slapstick comedy would be fatal here; the additional time is required to savor the acting and, depending on the scene, the either biting or clever dialogue. Hamilton is best remembered for his James Bond films, including Goldfinger and Diamonds Are Forever, where he does up the tempo.

The decade of the ’50s was James Mason’s most productive period. He was at the height of his popularity and made some of his best films. These movies are as good a testimony as any to his range as an actor. His Rommel in The Desert Fox emerges as a decent man, the victim of circumstances and an evil regime, even likeable despite being on the wrong side. In the same period—that same WWII!—he’s the urbane spy Ulysses Diello in Five Fingers. Hard and cool, he thinks he has covered all the contingencies—until the last scene. It is one of the great surprise endings in filmdom, Diello laughing on that balcony in Rio de Janeiro, casting into the wind those assiduously acquired British pound notes—all master forgeries.

The decade of the ’50s was James Mason’s most productive period. He was at the height of his popularity and made some of his best films. These movies are as good a testimony as any to his range as an actor. His Rommel in The Desert Fox emerges as a decent man, the victim of circumstances and an evil regime, even likeable despite being on the wrong side. In the same period—that same WWII!—he’s the urbane spy Ulysses Diello in Five Fingers. Hard and cool, he thinks he has covered all the contingencies—until the last scene. It is one of the great surprise endings in filmdom, Diello laughing on that balcony in Rio de Janeiro, casting into the wind those assiduously acquired British pound notes—all master forgeries.

Although in The Prisoner of Zenda Mason is saddled with a scene-by-scene remake of the much better 1937 original, his Rupert is every bit as dastardly as Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.’s in the earlier version. Mason’s villainy is of a different, higher sort in Julius Caesar. In one of Brutus’ best soliloquies, he ponders, “Therefore think him as a serpent’s egg/Which, hatch’d, would, as his kind, grow mischievous,/And kill him in the shell.”

As the maleficent Captain Nemo of the “Nautilus” in Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, he moves about his submarine assured and resolute. “I have done with society,” he says, ”therefore I do not obey its laws.” In many ways—for its intellectual approach and dynamic intensity—this performance is greatly underestimated and neglected. He dominates the other actors (Kirk Douglas, Paul Lukas and Peter Lorre) much as he does in Larceny.

As the maleficent Captain Nemo of the “Nautilus” in Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, he moves about his submarine assured and resolute. “I have done with society,” he says, ”therefore I do not obey its laws.” In many ways—for its intellectual approach and dynamic intensity—this performance is greatly underestimated and neglected. He dominates the other actors (Kirk Douglas, Paul Lukas and Peter Lorre) much as he does in Larceny.

In his next film A Star is Born, made the same year (1954) as Leagues, his character is not so assured. Far from it. As Norman Maine, an alcoholic actor on the way down, he plays opposite Judy Garland as Esther Blodgett, a young actress on her way up. For this role Mason received his first and only Best Actor Oscar nomination, losing to Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront.

His ability to play the suave villain who never soils his hands or his clothes culminates in Philip Vandamm in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. Always dressed in a dark suit and moving as though he were in a drawing room (as sometimes he is), he has his two henchmen do his dirty work, injecting an occasional good line among Cary Grant’s many. At the art auction, after Roger Thornhill (Grant) has implied that only his playing dead will satisfy Vandamm, Mason intones, “Your very next role. You’ll be quite convincing, I assure you.”

Back to a Verne story in 1959. Journey to the Center of the Earth has several things going for it—not, though, the cardboard and plaster sets—among them the lovely Arlene Dahl and Bernard Herrmann’s subterranean score, perfect support for an expedition into the bowels of the earth. Mason’s lightly played Oliver Lindenbrook spends much of the time exasperated by the demands of a strong woman (Dahl). There’s also in tow Pat Boone, Icelandic actor Peter Ronson, Thayer David as the requisite villain and, of course—not to be forgotten—Gertrude. A second actress? No . . . a duck!

Back to a Verne story in 1959. Journey to the Center of the Earth has several things going for it—not, though, the cardboard and plaster sets—among them the lovely Arlene Dahl and Bernard Herrmann’s subterranean score, perfect support for an expedition into the bowels of the earth. Mason’s lightly played Oliver Lindenbrook spends much of the time exasperated by the demands of a strong woman (Dahl). There’s also in tow Pat Boone, Icelandic actor Peter Ronson, Thayer David as the requisite villain and, of course—not to be forgotten—Gertrude. A second actress? No . . . a duck!

From the Lindenbrook character, the actor moved effortlessly, even naturally, to another light role in his next film, A Touch of Larceny, his last of the ’50s.

Following that decade, Mason was nominated in 1966 for Best Supporting Actor for Georgy Girl as the middle-aged James Leamington who desires Georgy (Lynn Redgrave) as his mistress. His only other nomination, in the same category, came in 1982 toward the end of his career as a defense lawyer challenging Paul Newman in The Verdict.

Following that decade, Mason was nominated in 1966 for Best Supporting Actor for Georgy Girl as the middle-aged James Leamington who desires Georgy (Lynn Redgrave) as his mistress. His only other nomination, in the same category, came in 1982 toward the end of his career as a defense lawyer challenging Paul Newman in The Verdict.

In Larceny, Mason is Commander Max “Rammer” Easton, a WWII submarine hero who, along with his newspaper- and pocketbook-reading staff, idles away time at the Admiralty. Reserving the squash court makes for a hard day! In the film’s opening scene, the wily, philandering commander’s love-making is interrupted by the arrival of the woman’s husband. “You didn’t tell me you were married!”

Then Easton meets Virginia (Miles) when diplomat Charles Holland (Sanders) gives him a lift in his chauffeured car. Demurely beautiful, she sits in the back seat, not in the least taken with the commander, who oozes charm and immediately hits on her. When Holland introduces her as Mrs. Killain, Easton declares he once knew a man named Killain—in Baltimore, “a most charming man”—and wonders if he could be her husband. Speak of a pathetic line! Holland interjects that she is a widow, and Virginia, as aware as the audience of the absurd ruse, remarks that it is an understandable mistake, since “Killain” isn’t a common name!

Before being dropped off at his flat, Easton, far from perturbed, steals one of her gloves from the seat between them. The next day he calls her and innocently asks if she had, by chance, lost a glove. “As a matter of fact,” she responds, “I have.” She’s still wise to him.

Before being dropped off at his flat, Easton, far from perturbed, steals one of her gloves from the seat between them. The next day he calls her and innocently asks if she had, by chance, lost a glove. “As a matter of fact,” she responds, “I have.” She’s still wise to him.

Having insisted on bringing the glove by her flat, he says how impressed he is by “old Charles” (for knowing a dish like Virginia), but that Charles is a typical diplomat—“tall, elegant, highly respectable—and rather dull.” As he sips his drink, Virginia announces that she and Charles are engaged. Gulp!

An American couple arrive and, in deciding on a good restaurant, Easton suggests a former cellar built by Napoleonic prisoners, but he feigns that it’s hard to find and finagles an invitation from the elderly couple. The restaurant, he says, is called The Sly Old Fox. What’s blatantly obvious is that Easton, lounging against the fireplace mantel, drink in hand, looking debonair and unruffled by any glare Virginia can throw his way, could just as easily be “the sly old fox.”

During Charles’ ten-day absence, Easton convinces Virginia to have lunch on his ship. As they zip along in his little sports car, she wonders if his “ship” will be a battleship, a cruiser or maybe—no, no, surely not!—a submarine. No, he promises her, not a submarine. And he’s humming all the time. When they arrive at the dock, his “ship” turns out to be . . . a little sailboat!

While they jointly navigate the skip, Easton hatches, on the spot, a theoretical scheme to acquire as much money as her fiancé, since she is apparently marrying for money, and, as “incentive” as Easton calls it, win the hand of Virginia in the bargain. He will hide a top secret file behind a filing cabinet, then disappear while on leave. He will sink his sailboat and maroon himself on a little island off of Scotland.

The press, he tells her, will assume the file has been stolen and, along with the incriminating, though circumstantial evidence he plans to leave behind, the newspapers will soon publish libelous statements about him. Per the plan, after his rescue it will be revealed that his disappearance was all innocent coincidences, and he will sue the newspapers for libel, make a fortune and marry the waiting Virginia.

The press, he tells her, will assume the file has been stolen and, along with the incriminating, though circumstantial evidence he plans to leave behind, the newspapers will soon publish libelous statements about him. Per the plan, after his rescue it will be revealed that his disappearance was all innocent coincidences, and he will sue the newspapers for libel, make a fortune and marry the waiting Virginia.

Returning in the sports car, Easton informs her that their date isn’t over. In a most romantic scene in a nightclub, they dance to “The Nearness of You” by Hoagy Carmichael and Ned Washington. Cinematographer John Wilcox (Young Frankenstein, 1978, The Eagle Has Landed, 1976, etc.) employs numerous tight close-ups as the pair come close to kissing. There is no dialogue until she says, “Take me home, Max.”

Composer Philip Green is perhaps best known for The League of Gentlemen (1963), but his score here, although fluffy and appropriate to the film, is not particularly outstanding. When Easton drops Virginia at her flat and asks her to marry him, the music becomes tender, with hushed, almost wraithlike string harmonies, but it is impressive, once again, because of the setting of the Carmichael tune. She turns down his proposal, but it’s obvious she has enjoyed their time together.

Still undeterred, Easton launches his scheme. He plants an incriminating note and other red herrings and performs a delightful charade at the Russian Embassy. He searches the crowd of foreign dignitaries until he finds a Russian who doesn’t understand English and proceeds to discuss the banana, a most unusual fruit he says, gesturing about its length and slightly curved shape, presumably to imply for onlookers that he’s describing a submarine or missile. The Russian even explains his paper money, the two passing the currency back and forth.

Easton later pretends to be drunk, even executing a deft fouetté, perhaps to attract attention, for being seen is essential to his ploy. As soon as he is out in a hall, out of sight of the crowd, he drops his stagger, brushes back his tousled hair and smiles smugly. It is reminiscent of The Maltese Falcon after Humphrey Bogart’s tough act in Sydney Greenstreet’s hotel room.

The commander makes other “incriminating” moves and sets sail. As expected, the plan works! Easton has overstayed his leave and is reported missing. Headlines proclaim he has been seen boarding the “Karl Marx” and been spotted in Warsaw. Virginia, aware of Easton’s scheme and that his rescue is necessary, deposits a bottle with a note for an unsuspecting boy to find.

Easton is rescued from the island—well and good—but there’s a problem. He’s caught off guard when an investigator (Lamont), already suspicious of the newly retrieved Robinson Crusoe, asks him a disquieting question:

If, indeed, he set adrift the bottle, then he’d know the kind of bottle and the wording of the note.

Easton is at a loss—he knows he used no bottles and is mystified that one was found in the first place. Fortunately, a brief distraction in the room gives him time to think. The investigator turns back to Easton. “Well, commander?—” He figures he’s got his man.

Easton is at a loss—he knows he used no bottles and is mystified that one was found in the first place. Fortunately, a brief distraction in the room gives him time to think. The investigator turns back to Easton. “Well, commander?—” He figures he’s got his man.

Easton casts his eyes at the ceiling—prayerfully, perhaps. “I’m afraid I have absolutely no idea.” He’s calm and once again in control of the situation. He adds that he doesn’t know which bottle was picked up! Why, he must have cast adrift countless bottles—with different messages, of course. Even Captain Graham supports him, suggesting that the investigator shouldn’t imagine Easton would rely on only one bottle.

It is perhaps the finest moment in the film.

Besides the ramifications of Virginia’s complicity in Easton’s scheme, Charles threatens to sue the commander for fraud. But, no, there’s a final twist to things—all right, besides the expected happy ending. Easton has decided to sell his “true” story. Virginia assumes he’s still going with Plan A. “No, darling,” he corrects, “how I miraculously survived without food or water after that terrible shipwreck.” Hum, he’ll make more money than if he sued the newspapers!

By all means, see A Touch of Larceny.

Unavailable on DVD or VHS (VH what?), the film probably exists, fleetingly, on TCM or another movie channel. Well worth the search, this light-hearted romantic comedy is never saccharine, with just the right ingredients of sweets (Miles) and spice (Sanders), and leavened with good portions of charm and rascality (Mason).

Thank you for this review. One of my favorite movies.

I finally found A Touch of Larceny, after much searching. It did not disappoint! The dance scene at The Sly Fox is one of the sexiest things I’ve ever seen — much more so than today’s no-mystery sex scenes, much more convincing than Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman in a similar moment in Notorious. I’ll be watching this funny, seductive film again.

Absolutely!!! This entire review is one of the best I’ve ever read about movies and acting in general.

This movie, said to say, was WAY too sophisticated for the average American audience and even most American “critics”. The timing, especially when Mason manages to inveigle his way into Mile’s apartment early in the movie, is priceless.

Sad (not said)