Gethryn learns from Mrs. Slattery that the victim was James, masquerading for Joe’s insurance, and that he, James, had indeed served in Burma—and that’s what the ten men, eleven counting Messenger, had in common. “Whatya say now, Jim? I knew there’d be an accident,” she says. “No, Mrs. Slattery, your son was murdered.”

Next comes a somewhat comic scene, providing a major clue, a revelation, in fact. Gethryn and Le Borg visit Mrs. Kouroudgian (Cooper), the former wife of Sir Francis Pomfret, who was also on Messenger’s list. At one point she lifts her glass for more wine, which her second husband Max obediently attempts to refill, though her little Pekinese yelps on cue. Mrs. Kouroudgian relates that Pomfret was part of a group of Burma POWs who were betrayed by some Canadian sergeant. She doesn’t know his name.

Next comes a somewhat comic scene, providing a major clue, a revelation, in fact. Gethryn and Le Borg visit Mrs. Kouroudgian (Cooper), the former wife of Sir Francis Pomfret, who was also on Messenger’s list. At one point she lifts her glass for more wine, which her second husband Max obediently attempts to refill, though her little Pekinese yelps on cue. Mrs. Kouroudgian relates that Pomfret was part of a group of Burma POWs who were betrayed by some Canadian sergeant. She doesn’t know his name.

After Gethryn and Le Borg have left, Max boasts that Pomfret was related to the Marquis of Gleneyre, the “Brutt-en-holms,” as he pronounces it. Mrs. Kouroudgian corrects him: it is pronounced “B-r-o-o-o-m.” He protests, “But it is spelled ‘Brou——’ ” “I don’t care,” she interrupts, “how it is spelled. ‘B-r-o-o-o-m.’ Oh, I wish you’d learn to speak English!” She lifts her wine glass once more. Max, as before, scrambles to fill it but, again, the lap dog yelps in protest.

(Interesting. Until now the name “Bruttenholm” has been pronounced only once during the film, and then by Le Borg as “Brutt-en-holm”—in the hospital to Joyelyn, who did not correct him. Huston and Veiller, it seems, are guilty of withholding essential information, the true crux of the mystery, until the last possible moment! They are revealing the clue only for their audience, not quite yet for the one player who needs to know. Le Borg wasn’t present—by design?—to learn of his “brush” error through Mrs. Kouroudgian’s elocution lesson. In the novel, Le Borg wasn’t in the scene, nor was Max, nor the mention of the family name. Also interesting—a possible script slip?—is that Max pronounced the word “Brutt-en-holm” but attempted to spell it “Brougham,” a word which won’t arise until the next scene.)

Scotland Yard has discovered that a Canadian sergeant was, indeed, in the POW camp, a George Brougham—spelled differently but also pronounced “Broom,” as Gethryn points out. Le Borg, not present, has missed out again on learning his mistake!

In perhaps the longest—and best—of Scott’s many analyses, he hypothesizes to Sir Wilfred and Le Borg the motive for the killings—inheritance, in short, the estate of Gleneyre, and that this George Brougham, son of the Marquis’ brother, must eliminate those fellow POWs who could expose his treachery when he comes forward to make his claim. As Gethryn said, he could afford to wait, “in the natural course of events,” for an 80-year-old man to die, that it was, rather, the next in line who was in real danger, young Derek (Tony, John Huston’s son).

In perhaps the longest—and best—of Scott’s many analyses, he hypothesizes to Sir Wilfred and Le Borg the motive for the killings—inheritance, in short, the estate of Gleneyre, and that this George Brougham, son of the Marquis’ brother, must eliminate those fellow POWs who could expose his treachery when he comes forward to make his claim. As Gethryn said, he could afford to wait, “in the natural course of events,” for an 80-year-old man to die, that it was, rather, the next in line who was in real danger, young Derek (Tony, John Huston’s son).

This same scene has a vital and more dramatic second half. While the first half is without music—none is needed to accompany cold facts—the second is greatly enhanced by Goldsmith’s eerie support. After his eloquent dissertation, Gethryn, takes from the fireplace a shovel and broom and sweeps up some stray ashes. Holding the broom, he hesitates. Turning to Le Borg, he asks him, “What do you call this?” “Un balai.” “Not in French, in English.” “A brush, a brush for the floor.”

Gethryn suggests that Le Borg return his memory to that “cruel sea.” Standing behind him, Gethryn recites what both men have come to believe were Messenger’s last words, only now—— “Only one broom . . . only one broom left . . . ” Le Borg agrees that was what Messenger had said but is puzzled why “broom” should mean more than “brush.” Gethryn explains that “Bruttenholm” is the family name of the Marquis of Gleneyre, which Le Borg hadn’t realized, and he, too, had pronounced it as three syllables and, like the audience, had never heard the word spoken. In the novel, Gethryn attributes this phonetic muddle to “an Anglo-Saxon idiosyncrasy.”

A gypsy (Sinatra) emerges from the English fog to present Derek with a belated gift from Adrian Messenger, a horse named Avatar. Sound familiar these days? The horse is “gypsy-trained,” he says, and teachers the boy to control the animal with stop and go commands.

A gypsy (Sinatra) emerges from the English fog to present Derek with a belated gift from Adrian Messenger, a horse named Avatar. Sound familiar these days? The horse is “gypsy-trained,” he says, and teachers the boy to control the animal with stop and go commands.

Because of Huston’s interest in fox hunting—he lived in Ireland for eighteen years and rode with several hunting groups—he added two extensive fox hunting sequences to the latter part of his movie. In the first, George Brougham shows up, now undisguised since he thinks he’s eliminated all those who could identify him. Now he can be, as Gethryn says, his own charming self. The Marquis, unaware of his crimes, welcomes to the family his brother’s son—another Bruttenholm, regardless of how he misspells it.

Set to the reckless pace of horses and hounds traversing fields, jumping stone walls and fording streams, Jerry Goldsmith’s “hunting” music is exciting, with much élan, the main rhythm/tune faintly reminiscent of the opening of the trio of the scherzo of Anton Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony, too faint to suggest anything more than pure coincidence. This music is more like the open outdoors, certainly lighter and brighter—one is hesitant to say “better”—than Bernard Herrmann’s for the foxing hunting scene in Marnie.

During a game of cards after dinner, Jocelyn begins playing Chopin’s Nocturne in E-Flat, Op. 9, No. 2. No mention had been made of her prowess as a pianist. Too, just coincidentally, there is a second piano. The now debonair Brougham, who has even spoken some French!, accompanies her in an extemporaneous duet, not composed by Chopin. A little improbable that Brougham would be both a pianist and familiar enough with the nocturne to play so expertly on the spot. No matter. Le Borg, who was smitten with Lady Bruttenholm from their meeting in the hospital, looks up uneasily from the card game at the two transfixed pianists.

During a game of cards after dinner, Jocelyn begins playing Chopin’s Nocturne in E-Flat, Op. 9, No. 2. No mention had been made of her prowess as a pianist. Too, just coincidentally, there is a second piano. The now debonair Brougham, who has even spoken some French!, accompanies her in an extemporaneous duet, not composed by Chopin. A little improbable that Brougham would be both a pianist and familiar enough with the nocturne to play so expertly on the spot. No matter. Le Borg, who was smitten with Lady Bruttenholm from their meeting in the hospital, looks up uneasily from the card game at the two transfixed pianists.

Later that evening, Gethryn tells Brougham about that page 174, that possibly a name had been omitted from Messenger’s account of his Burma service, that Scotland Yard should be able to put together a complete list of the men who were with Messenger in the POW camp. Yes, Gethryn has deliberately set himself up as a target.

Sure enough, on Brougham’s walk the next day, he calls Gleneyre from a pay phone, posing as lawyer Arthur Henderson, who must see Brougham in London the next day. Brougham departs, reminding Gethryn to stay out in front in the next day’s hunt. With a bagged fox, he drags the sack across the countryside, ending at a stone wall, beyond which he places a heavily spiked farm machine.

Jerry Goldsmith’s music for the next day’s fox hunt begins ominously, the earlier élan missing, though into the chase things brighten and the hunting calls return in full splendor. During the hunt, there are spectators and protesters, as fox hunting is regarded now by most in England as a repellent blood sport. Among the crowd is a heavy-set woman wearing a head scarf, carrying a sign and quoting Oscar Wilde: “The unspeakable after the uneatable.” The camera focuses on several other individuals. Gethryn and Le Borg realize that any one of them could be Brougham in another disguise.

Abruptly, the hounds stop at a wall, the scent of the fox gone. The spiked machine has been removed. “We’ve been following a drag!” the Marquis shouts. John Huston, in black silk top hat and full hunting regalia, declares, “Drag? At Gleneyre? Unheard of. Ruin the hunt’s reputation.” Gethryn explains that, before the hunt, he and a dog and his master had followed the drag and discovered and removed the machine.

Abruptly, the hounds stop at a wall, the scent of the fox gone. The spiked machine has been removed. “We’ve been following a drag!” the Marquis shouts. John Huston, in black silk top hat and full hunting regalia, declares, “Drag? At Gleneyre? Unheard of. Ruin the hunt’s reputation.” Gethryn explains that, before the hunt, he and a dog and his master had followed the drag and discovered and removed the machine.

Now, Gethryn says, the dog will sniff out the culprit among the spectators. The animal moves from person to person—a man with a shotgun, the heavy-set woman with the scarf, a bearded man (the uncredited Noel Purcell who had been in John Huston’s Moby Dick and the Marlon Brando remake of Mutiny on the Bounty) and, finally, a farmer. The farmer suddenly breaks and jumps on Avatar, spurring the horse toward the wall. Derek calls for his horse to halt. The animal lands on the wall, throwing the rider over its head.

There’s a scream. Horsemen and camera peer over the wall: there, impaled on the spikes of the farm machine, is the farmer, pulling away part of his disguise before he dies. George Brougham! (Earlier, the machine had been seen pulled away over a distant hill!) From Goldsmith comes eight identical metallic fortissimo shrieks, like fingernails on a blackboard, and a final quoting of the “villain” theme, now at a slow tempo and in an agonizing tone.

There’s a scream. Horsemen and camera peer over the wall: there, impaled on the spikes of the farm machine, is the farmer, pulling away part of his disguise before he dies. George Brougham! (Earlier, the machine had been seen pulled away over a distant hill!) From Goldsmith comes eight identical metallic fortissimo shrieks, like fingernails on a blackboard, and a final quoting of the “villain” theme, now at a slow tempo and in an agonizing tone.

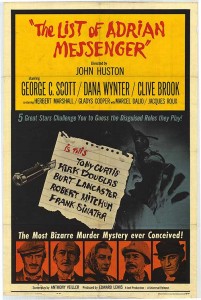

As the horsemen are riding off, “The End” appears on screen but a voice intones, “That may be the end of the picture, but it’s not the end of the mystery.” Then step forward the actors in their Westmore make-up, accompanied by the music associated with them. They remove their make-up, winking, smiling, bowing or gesturing for the camera: Tony Curtis as the organ grinder, Burt Lancaster as the heavy-set woman, Frank Sinatra as the gypsy and Robert Mitchum as Slattery. Accompanied by variations of the “villain” music, Kirk Douglas walks through his various disguises, then, in the last as the farmer and suddenly aware of the camera, he turns, unmasks himself and says, “The End.”

As long as we’re spoiling the entire movie for no other reason than to make ourselves look informative…

At least I’ll leave one mystery for the reader to discover on their own: Through some research on IMDB and a perusal of a John Huston biography I’ve discovered that the men behind the make-up may NOT have been those advertised. See the film, do the reading — And try to forget what you’ve read above. The film is a true guilty pleasure, one that will stay with you…

And one that should not have been spoiled.

Why not mention that the film was severely cropped for this DVD release? It’s especially noticeably that the bottom of the image was cut off. The sides may have been cropped as well. The result is that the composition is terrible in about half the shots, and in many shots you can’t see what the actors are doing with their hands. The cropping of films released on DVD is widespread, and ought to be loudly decried by everyone who loves the cinema.

I’ve read the original novel. It’s quite good. The problem was Huston’s adaptation. It was lazy and gimmicky. I hope there will be a remake of this story one day.

This film has always stuck with me. It’s unusual, inventive, and gripping. Goldsmith’s score is terrific, and the entire concept of deception is ably embraced.

Yes. I said as a “terrified ” 7 year old. I’ve always wondered why it’s never been shown on TCM.

Saw this film so long ago! It always was high on my list. I looked at the film as a tongue in cheek plot. So interesting now to see those stars in their prime. Opinion: I do not feel the press was accepting of Huston’s work! I can recall nearly the entire plot, visually, after 50+ years.

Being sensitive to animal welfare I was a little disturbed by the scene where a fox was held by a rope round it’s neck and bundled into a sack and the scene at the end where a horse straddles a wall and is clearly hurt. I realise this film was made in the days before concern for animals was of importance in movies and John Huston was renown for his uncaring attitude towards them(White Hunter Black Heart was about him I believe). Even so it left a bad taste and ruined what was already a flawed film made memorable only for the heavily disguised film stars.