One scene is especially memorable—and pathetic. Speer has defied Hitler in instigating his scorched earth policy, that is, decimating everything before the advancing armies. Speer insists that farm and industry be left intact for the rebuilding of the country after the war. Hitler retorts that all the good Germans have died, those left behind are unworthy of survival. He orders Speer to take a leave of absence to think over his position and, furthermore, to assure him that he, Speer, believes the war is not lost. This scene is quite extensive, both in the film and in Speer’s book, the Führer pleading and insisting, even relaxing the criterion enough so that Speer need only express a “faith” that the war is not lost.

One scene is especially memorable—and pathetic. Speer has defied Hitler in instigating his scorched earth policy, that is, decimating everything before the advancing armies. Speer insists that farm and industry be left intact for the rebuilding of the country after the war. Hitler retorts that all the good Germans have died, those left behind are unworthy of survival. He orders Speer to take a leave of absence to think over his position and, furthermore, to assure him that he, Speer, believes the war is not lost. This scene is quite extensive, both in the film and in Speer’s book, the Führer pleading and insisting, even relaxing the criterion enough so that Speer need only express a “faith” that the war is not lost.

A short detour here. Actors in minor roles are fun to spot. In The Bunker, Michael Kitchen, a personal favorite, plays radio technician Rochus Misch. As here, Kitchen often seems most comfortable in low-key, understated roles—as in two of his other films I cite at random: in Enchanted April (1992) as George Briggs who plays Elgar’s “Chanson de Martin” on his oboe (remember?), and, currently, in PBS’s series Foyle’s War as Chief Inspector Christopher Foyle. In a recent episode, “Killing Time,” about interracial conflict among American soldiers in the U.K., Foyle’s is the only vote against a city council wanting to segregate the bars. “We have no segregation in England,” he says in what seems like a casual defense of his position, but the line as Kitchen speaks it carries considerable weight.

Anthony Hopkins won an Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Limited Series or a Special and Piper Laurie was nominated in the same category as best actress as Magda Goebbels.

Unlike the first two films, which are claustrophobically limited to inside the bunker, Downfall (2004) goes outside the bunker as well, to show the defense of Berlin against the advancing Russians, including the Hitler Youth fighters, the desperate conditions of the hospitals and the activities of vicious squads which execute deserters.

Unlike the first two films, which are claustrophobically limited to inside the bunker, Downfall (2004) goes outside the bunker as well, to show the defense of Berlin against the advancing Russians, including the Hitler Youth fighters, the desperate conditions of the hospitals and the activities of vicious squads which execute deserters.

The screenplay is based on Inside Hitler’s Bunker by German historian Joachim Fest and on the memories of one of Hitler’s secretaries, Traudl Junge, who died in 2002, the year of her memoir. She appears at the conclusion of the film with some relative comments. As in The Bunker, the fates of the historic individuals involved are summarized.

Bruno Ganz, perhaps best known to American and English audiences as Professor Rohl in The Reader (2008), is the Führer. His is easily the most horrific of the portrayals, first, because he most resembles Hitler and, second, because the tirades, devastating in themselves, sound more “brutal” in German, to use, from Amadeus, Kapellmeister Bonno’s term for the guttural qualities of that language. Ganz convincingly displays the physical deteriorations that took place—the shaking left hand, the fatigue, the stooped posture, though I didn’t notice the dragging of one foot, the loss of balance or the drooling. (By contrast, Guinness’ Hitler seems generally healthy, physically.) All evidence now suggests that, as early as 1942, Hitler was suffering from Parkinson’s disease.

Bruno Ganz, perhaps best known to American and English audiences as Professor Rohl in The Reader (2008), is the Führer. His is easily the most horrific of the portrayals, first, because he most resembles Hitler and, second, because the tirades, devastating in themselves, sound more “brutal” in German, to use, from Amadeus, Kapellmeister Bonno’s term for the guttural qualities of that language. Ganz convincingly displays the physical deteriorations that took place—the shaking left hand, the fatigue, the stooped posture, though I didn’t notice the dragging of one foot, the loss of balance or the drooling. (By contrast, Guinness’ Hitler seems generally healthy, physically.) All evidence now suggests that, as early as 1942, Hitler was suffering from Parkinson’s disease.

Downfall has English subtitles. Not quite as annoying as mouth/voice disparity in dubbing another language, subtitles are distracting: I feel I’m missing some of the visuals while I’m busy reading. Reading is for books!

The suicides of Hitler and Braun occur off screen. The group in the bunker witness the aftermath—blood stains, a revolver and Eva’s shawl and handbag. In director Oliver Hirschbiegel’s excellent commentary—one of the best: straightforward, modest and unscripted—he asserts that he didn’t show this scene since no one witnessed it; nor did he want to create a myth or mistakenly imply heroism.

The suicides of Hitler and Braun occur off screen. The group in the bunker witness the aftermath—blood stains, a revolver and Eva’s shawl and handbag. In director Oliver Hirschbiegel’s excellent commentary—one of the best: straightforward, modest and unscripted—he asserts that he didn’t show this scene since no one witnessed it; nor did he want to create a myth or mistakenly imply heroism.

Incongruously, Magda Goebbels’ murder of her children is shown. As best I remember from accounts of life in the bunker, this wasn’t witnessed either. The scene is rather unnecessarily protracted, and anyone who loves children will find it very hard to watch as Magda breaks a cyanide capsule in the mouth of each of her six children, already sedated.

At first I was surprised by the omission of the news of Roosevelt’s death, which caused such euphoria among those in the bunker, yet another sign for Hitler of a turnabout victory. When I watched Downfall a second time, I realized Downfall begins April 20 and F.D.R. had died on the twelfth.

Speer wrote in Inside the Third Reich that the slightest event was occasion enough for Hitler to prophesy an about-face of his fortunes. Even on New Year’s 1945—and 1945 had to be the bleakest New Year of Hitler’s “Thousand Year Reich”—Speer had gone to see the Führer, then burrowed in another bunker at Bad Nauheim, to convey best wishes. Speer wrote: “After more than two hours, during which Hitler spread around his credulous optimism, his followers, including myse lf, were transported in spite of all their skepticism into a more sanguine state.”

lf, were transported in spite of all their skepticism into a more sanguine state.”

Director Hirschbiegel observed in his commentary that Albert Speer knew all about the Final Solution, an awareness he had always denied and a ploy which undoubtedly saved his skin at the Nuremberg Trials; that Speer was the most cultured and sophisticated of the high-ranking Nazis around Hitler—though, really, not all that hard to do—is commonly accepted.

But Hirschbiegel regarding Speer as “a great architect” cannot go unchallenged. Speer’s buildings—parts of his Zeppelinfeld stadium in Nuremberg remain—were heavy and ungraceful, with bloated exaggerations of Roman and Greek architecture, everywhere columns and pilasters, large, blockish monoliths and, as always with the Nazis, big, BIG, BIG. I think the consensus is that Speer was quite less than a genius, perhaps even a mediocre architect, his heavy style obviously reflecting Hitler’s own egomaniacal taste.

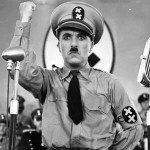

The continuing fascination with Hitler is reflected in numerous theatrical and TV movies, beyond the three I’ve discussed. While Hitler was still alive, Charlie Chaplin had assimilated the comic aspects of the strutting marionette, as someone has called Adolf, in Adenoid Hynkel in The Great Dictator of 1940. About the same time Robert Watson (1888-1965) began playing the madman, more than anyone else as it turns out, in at least eight films between 1942 and 1962, including his last, The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse, about a family divided by WWII.

The continuing fascination with Hitler is reflected in numerous theatrical and TV movies, beyond the three I’ve discussed. While Hitler was still alive, Charlie Chaplin had assimilated the comic aspects of the strutting marionette, as someone has called Adolf, in Adenoid Hynkel in The Great Dictator of 1940. About the same time Robert Watson (1888-1965) began playing the madman, more than anyone else as it turns out, in at least eight films between 1942 and 1962, including his last, The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse, about a family divided by WWII.