Commentaries more astute than mine have indicated that much of Wonderful Life is inspired by Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol—evident, first, in angel Clarence coming to earth to help George Bailey. The scene where Clarence shows George the grave of his brother who wasn’t, after all, saved from drowning since George wasn’t alive to rescue him, is right out of Dickens, the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come. (A clever touch is the transformation of George’s low-cost housing development in Bedford Falls into a bleak cemetery in Pottersville, which the town became without George’s presence.)

There are numerous differences between these two films. Mr. Deeds is more innocent and direct, simpler, less theatrical and philosophical in any possible messages. Wonderful Life is more multilayered, with higher production values, most conspicuous in several city blocks of the downtown Bedford Falls set and a better score (by Dimitri Tiomkin).

While Gary Cooper is of the acting school where less is more, James Stewart takes advantage of the greater dramatic depth in his film, a kind of anger, other times terror, that hadn’t been seen in his earlier films. During his and Mary’s shared phone conversation with Wainwright, he first shakes her and shouts he doesn’t want to be tied down, then kisses her frantically, unable, it seems, to live without her. When he comes home to his family that Christmas Eve, unable to find the missing $8,000 Uncle Billy has misplaced, he virtually destroys a room, reminiscent of Orson Welles’ similar rage in Citizen Kane. And when his mother (Beulah Bondi) doesn’t recognize him, there’s that wide-eyed stare into the camera.

I’ve been in love with the old movies all my life. When I occasionally see a current movie with its bang-boom-slam-blam-zip-zap presto tempo—in cutting, acting, sound—I’m reminded, especially after these recent viewings of Mr. Deeds and Wonderful Life, how leisurely these old films are plotted and photographed, with long stretches of dialogue and single camera shots lasting sometimes minutes on end. It’s understandable, at least from my perspective, that watching a trailer is usually as close as I wish to come to nowadays attempts at film making—Eclipse, Letters to Juliet, the “new” Robin Hood and most of their breed.

As for pacing, take Mr. Deeds for a starter, just one of many instances. In the trial scene, think of the many questions Deeds asks the Faulkner sisters about their house and who’s pixilated! As if Capra has all day, the point is driven home over and over, that, yes, the sisters believe everyone in Mandrake Falls is pixilated, except themselves: a long way to the punch line. The same with Wonderful Life. It’s interesting and well done, but why do the screenwriters reiterate that no one, absolutely no one, recognizes the never-been-born Bailey?—not Nick the bartender in one scene, not Mary in another, not policeman Bert nor cab driver Ernie, not the local trollop in yet another scene and, yes, there’s one more—not even his mother knows him! No, no, I’m not complaining; I’m just observing how different things are today—and not, I believe, for the better.

As for pacing, take Mr. Deeds for a starter, just one of many instances. In the trial scene, think of the many questions Deeds asks the Faulkner sisters about their house and who’s pixilated! As if Capra has all day, the point is driven home over and over, that, yes, the sisters believe everyone in Mandrake Falls is pixilated, except themselves: a long way to the punch line. The same with Wonderful Life. It’s interesting and well done, but why do the screenwriters reiterate that no one, absolutely no one, recognizes the never-been-born Bailey?—not Nick the bartender in one scene, not Mary in another, not policeman Bert nor cab driver Ernie, not the local trollop in yet another scene and, yes, there’s one more—not even his mother knows him! No, no, I’m not complaining; I’m just observing how different things are today—and not, I believe, for the better.

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town unfolds against the backdrop of the Great Depression, as did My Man Godfrey, another film in 1936 about the continuing economic bust of the 1930s. Both films lifted the spirits of their audiences and were well attended. By contrast, It’s A Wonderful Life, with its depressing last third, didn’t quite congeal with the euphoria following World War II. At the time, it was already regarded as old-fashioned, a throwback to the naïve, folksy, feel-good films of Capra’s pre-war successes. It was generally rejected by both critics and audiences, only rediscovered when its copyright protection expired without renewal and PBS began showing it at Christmas in the 1970s.

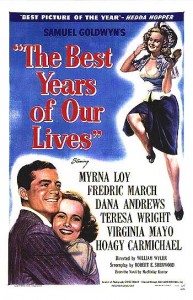

The film’s conceivable “companion” in 1946, if for no other reason than both directors were WWII veterans, was The Best Years of Our Lives, directed by William Wyler. The story of three returning veterans adjusting to civilian life was acclaimed by critics and won seven Oscars, a marked difference from Wonderful Life, which reaped no wins from its five nominations. Frank Capra was jealous of Wyler’s achievement. Perhaps he shouldn’t have been: Best Years has started, some say (not me), to show its age; Wonderful Life seems to grow fresher, somehow more relevant, with time.

The film’s conceivable “companion” in 1946, if for no other reason than both directors were WWII veterans, was The Best Years of Our Lives, directed by William Wyler. The story of three returning veterans adjusting to civilian life was acclaimed by critics and won seven Oscars, a marked difference from Wonderful Life, which reaped no wins from its five nominations. Frank Capra was jealous of Wyler’s achievement. Perhaps he shouldn’t have been: Best Years has started, some say (not me), to show its age; Wonderful Life seems to grow fresher, somehow more relevant, with time.

Capra’s jealousy brings up an unhappy footnote to these two wonderful films. Capra the man was quite different from the presumed image of someone who could make such optimistic, sentimental films about ideal family life and patriotism, stories of goodness and redemption. Make no mistake, Capra had a sure visual sense and an expert at handling his stars, knowing how to obtain the best from them with kindness and camaraderie.

But he was egomaniacal, jealous of others’ successes, full of self-doubts and unworthiness about himself as a creative artist. He always played down the importance of his fellow artists, cameramen and screenwriters in particular, and even maneuvered to steal credit from others. This all intensified toward the end of his life when the six films after Wonderful Life were devoid of the Capra magic and his health began to fail. He always thought being a great writer was superior to being a great director, and he believed his autobiography, The Name Above the Title, published in 1971, proved that. It was, in fact, one of the greatest whitewashes in Hollywood history, more fiction than fact, often asserting he had done everything himself and omitting many situations which showed him in a bad light.

Sure, the world had dramatically changed in the ten years between 1936 and 1946, partly because of WWII but also from the growing negatives in Capra’s psyche. Over the long haul, unlike Michael Curtiz, William Wyler and Alfred Hitchcock, he proved less versatile as a director, less adaptable to the changing times and tastes of his audience.

It’s been said that an artist’s work is the important thing to remember, not the artist himself. Take Richard Wagner. Deems Taylor called him “a monster of conceit,” one of the most unpleasant individuals who ever lived, but what glorious music he wrote! So with Capra. What do the frailties of Capra the man matter? Maybe they were necessary to make possible the films, maybe they grew out of the films. Who knows.

In the long run, up there on the screen, it’s the best of Frank Capra’s work we see: not only Mr. Deeds Goes to Down and It’s a Wonderful Life but It Happened One Night, Lost Horizon and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. After all, and rightly so, who ever looks behind the screen.

Sometimes, one should look behind the screen. Those people, whoever they might be, are the only reason the screen is not showing the pure white light of stupidity.

I am not one for gossip, or the endless collecting of media peoples’ minutiae, but it must be kept in mind that many people, not just the actors, not just the directors, make the movies possible. These people are not illegal aliens hidden in sweatshops, but they do perform important work.

Every product has a process behind it. Our culture tends to glorify the product, while pretending there is no process involved, and never has been. May Americans believe movies and such ‘just appear’. Not quite.

Although I took exception to the last sentence, the reviews/comparison was very interesting. I agree, newer movies are somewhat… empty. Our culture has become much too shallow.

“Many Americans believe…” is what I meant…