Master and Commander and Roy Adkins’ Masterful Battle of Trafalgar Book

But as for Master and Commander, the first image I had of the film was something of a surprise, which I hadn’t noticed on earlier viewings. I immediately felt I was actually below the decks of a ship not of this century, nor even the century before that. It was an audio image, more important in this instance, I felt, than the visual one—the turning of an hour glass, animals in their pens, a sailor climbing to a hatch, a gun carriage marked “SUDDEN DEATH.”

What did I hear? The creaking of masts, bulkheads, beams and timbers, of everything wooden, even of lanterns swinging, startlingly effective in stereo, astounding now that stereo is taken for granted. Hollywood in the “good old days” didn’t worry about such—maybe a creak here, a creak there, nothing more. Thereafter, I was only occasionally aware of the creaking, which, even topside, had a voice all its own—now of rigging and ratlines, masts and yards as they moved against one another. Like the noise of artillery in those Hitler bunker films, I assumed the sound was always there.

What did I hear? The creaking of masts, bulkheads, beams and timbers, of everything wooden, even of lanterns swinging, startlingly effective in stereo, astounding now that stereo is taken for granted. Hollywood in the “good old days” didn’t worry about such—maybe a creak here, a creak there, nothing more. Thereafter, I was only occasionally aware of the creaking, which, even topside, had a voice all its own—now of rigging and ratlines, masts and yards as they moved against one another. Like the noise of artillery in those Hitler bunker films, I assumed the sound was always there.

What was missing below decks in that opening scene, of course—impossible to convey on film—was what would have been, at least to modern sensibilities, the foulest-smelling air conceivable. According to Roy Adkins it would have been an atmosphere of rank, unwashed clothes, body odor, mold and an unrelieved dampness, and, if after a recent battle, the stench of burnt wood, gunpowder, even blood.

This is a good moment to introduce Adkins’ Nelson’s Trafalgar: The Battle That Changed the World, first published in the U.S. in 2005. I’ll be quoting it shortly, and it is highly, highly recommended. For those who haven’t seen Master and Commander, reading the book beforehand would be excellent preparation for an in-depth appreciation the film.

Master and Commander, untarnished by any glaringly obvious special effects, like no other film of its kind, captures the atmosphere, the color, practically the feel of the sea, of a ship’s roll and pitch—and the vast expanse of water, with its deep-troughed waves both awe-inspiring and threatening. The visuals are dampened by a subtle patina of steel blue, even in the bright sunlight of topside, that resembles old paintings, similar to director John Huston’s attempt to achieve the impression of steel engravings of sailing ships in his Moby Dick. One below-decks scene, with a single lantern, has the chiaroscuro of Rembrandt; his etching “Raising of Lazarus” comes to mind.

Master and Commander, untarnished by any glaringly obvious special effects, like no other film of its kind, captures the atmosphere, the color, practically the feel of the sea, of a ship’s roll and pitch—and the vast expanse of water, with its deep-troughed waves both awe-inspiring and threatening. The visuals are dampened by a subtle patina of steel blue, even in the bright sunlight of topside, that resembles old paintings, similar to director John Huston’s attempt to achieve the impression of steel engravings of sailing ships in his Moby Dick. One below-decks scene, with a single lantern, has the chiaroscuro of Rembrandt; his etching “Raising of Lazarus” comes to mind.

The leisurely tempo of the movie is another admirable feature. It allows for a nearly intimate acquaintance with the multitude of characters, another tie to the dialogue-rich movies of the ’30s and ’40s. Captain Aubrey himself (Russell Crowe) seems contradictory at times, as his surgeon and naturalist friend, Stephen Maturin (Paul Bettany), points out. The young Midshipman Blakeney (Max Pirkis), after his right arm is amputated, draws the sympathetic attention of Aubrey who gives him a book on the victories of Lord Nelson.

Life and Death Aboard His Majesty’s Ships of War

The lad, young as he was, undoubtedly realized that his chances of dying had been enormous. Sailors of that era, although their pay was equal to, sometimes better than, their land-based counterparts, had obviously a much shorter life expectancy. Apart from being blown to bits or succumbing to a variety of diseases, as Adkins points out, “ . . . in practical terms, medicine and surgery were still at the level reached by the Romans two thousand years earlier,” and had not appreciably improved by the time of the American Civil War some fifty years later.

The movie realistically illustrates, too, the devastation of a broadside, of a hail of 24- and 32-pound cannon balls slashing into wooden ships. In the early part of the film an unseen ship, out of the fog, fires at Aubrey’s ship. (Those French gunners must have been super-accurate indeed to have found the range, in fog besides, and scored a direct hit on the first salvo!) Speaking of stealing ideas, that sneaky broadside out of the fog was a feat already seen in the opening of the first Pirates of the Caribbean, The Curse of the Black Pearl, released four months earlier.

The ship battles in Master and Commander—a second one forms the climax of the film—convey the frightfully lethal power of an 18th-century broadside. But perhaps even students of naval strategy of the period have never thought of this scenario, brilliantly detailed by Adkins:

The planking of the sides of ships at the level of the gun decks was much less than thirty inches, and at close range with a high charge of gunpowder a cannon ball would enter through one side of the ship, spraying deadly wood splinters, before it carried on across the deck and through the opposite wall of the ship, destroying anything and anyone in its path. For this reason, as the range became shorter, the gunners reduced the amount of gunpowder in the cartridges to try to avoid the shot passing through both sides of the target; it would do far more damage by ricocheting around the cramped space of a gun deck in the enemy ship.

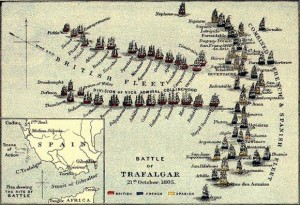

Adkins provides a time capsule of the maritime world in 1805—the terrible food and living conditions of the common sailor, cruel punishments from vindictive officers, the presence of women onboard (few records exist, but many commanders turned a blind eye), the crude medical care during battle, why ships were often already rotting when they were launched, a comparison of the warships of the three countries involved in the war, the science of sailing a ship and so much more. The brilliant, sometimes minute-by-minute, study of the Battle of Trafalgar, October 21, 1805, includes the names, armaments and commanders of the sixty-one vessels which participated—English, French and Spanish (Spain was cajoled into a misbegotten alliance with Napoleon).

Adkins provides a time capsule of the maritime world in 1805—the terrible food and living conditions of the common sailor, cruel punishments from vindictive officers, the presence of women onboard (few records exist, but many commanders turned a blind eye), the crude medical care during battle, why ships were often already rotting when they were launched, a comparison of the warships of the three countries involved in the war, the science of sailing a ship and so much more. The brilliant, sometimes minute-by-minute, study of the Battle of Trafalgar, October 21, 1805, includes the names, armaments and commanders of the sixty-one vessels which participated—English, French and Spanish (Spain was cajoled into a misbegotten alliance with Napoleon).

Facts and More Facts About Trafalgar

Interesting facts? They abound—if you’re interested in such! For instance, the news of the Trafalgar victory and Nelson’s death took ten days to reach the Admiralty. The message was taken by Lieutenant John Lapenotiere, first via his ship the Pickle from the coast of Cadiz to Falmouth in Cornwall, then eastward, by either post-chaise or horse, through Truro, Liskeard, Exeter, Bridport, Dorchester and the Salisbury Plain to London. Lapenotiere was followed, unknown to him, by a second messenger who wanted to be first with the news—all recounted in meticulous suspense by Adkins.

Interesting facts? They abound—if you’re interested in such! For instance, the news of the Trafalgar victory and Nelson’s death took ten days to reach the Admiralty. The message was taken by Lieutenant John Lapenotiere, first via his ship the Pickle from the coast of Cadiz to Falmouth in Cornwall, then eastward, by either post-chaise or horse, through Truro, Liskeard, Exeter, Bridport, Dorchester and the Salisbury Plain to London. Lapenotiere was followed, unknown to him, by a second messenger who wanted to be first with the news—all recounted in meticulous suspense by Adkins.

Another fact?— John Pringle, Nelson’s coxswain, died in 1863 at the age of 103. His obituary, in part, read: “Whilst in the service he took an active part in many of our celebrated naval battles, and among others those of the Nile, Trafalgar and Alexandria. He was in receipt of a pension, and at the ripe age of ninety-two he married, and his wife survives him.” It wasn’t mentioned herein whether or not Pringle wanted to join the Royal Navy or, possibly, was inducted against his will by one of the many notorious press-gangs—remember the opening of the 1935 version of Mutiny on the Bounty?

One more fact?— I had always wondered how far one could see across the ocean and Mr. Adkins conveniently satisfied my curiosity: “ . . . from the lookout station on the mainmast of a warship, over 100 feet above the waves, the furthest horizon was nearly 14 miles away, and the highest sails of another ship could be seen up to 20 miles off.” In Master and Commander, Russell Crowe stands on the main topgallant yard, á la Leonardo DiCaprio on the prow of the Titanic. But he does DiCaprio three better, however, by standing, at different times, on the bowsprit, on one of the ship’s chain-wales and on the transom.

One more fact?— I had always wondered how far one could see across the ocean and Mr. Adkins conveniently satisfied my curiosity: “ . . . from the lookout station on the mainmast of a warship, over 100 feet above the waves, the furthest horizon was nearly 14 miles away, and the highest sails of another ship could be seen up to 20 miles off.” In Master and Commander, Russell Crowe stands on the main topgallant yard, á la Leonardo DiCaprio on the prow of the Titanic. But he does DiCaprio three better, however, by standing, at different times, on the bowsprit, on one of the ship’s chain-wales and on the transom.

For those who don’t recognize—as I didn’t—the nautical origin of many still-in-use terms, Adkins explains the meanings of “slush fund,” “a square meal,” “scuttle-butt” and “going to the head.”

For those interested, Adkins extensively discusses the toilets on board, if they could be called that—when there were any at all. The limited ones which existed, called roundhouses (right), were located on either side of the bowsprit, in a part of the ship called the beakhead, a word already encountered in the Captain Blood excerpt. The easiest way, however, for the common sailor to “excuse himself” was to hang from the shrouds, with the direction of the wind and the lean of the ship being critical! Daily bodily functions were further compromised in bad weather; sailors would sometimes have to remain below decks for days, for venturing topside could risk being washed overboard. Guards were often posted at hatches to keep the men below. See, I’m sure few people think about these things when they see, in a movie, these beautiful ships under full sail and assume they’re as pristine as they appear!

For those interested, Adkins extensively discusses the toilets on board, if they could be called that—when there were any at all. The limited ones which existed, called roundhouses (right), were located on either side of the bowsprit, in a part of the ship called the beakhead, a word already encountered in the Captain Blood excerpt. The easiest way, however, for the common sailor to “excuse himself” was to hang from the shrouds, with the direction of the wind and the lean of the ship being critical! Daily bodily functions were further compromised in bad weather; sailors would sometimes have to remain below decks for days, for venturing topside could risk being washed overboard. Guards were often posted at hatches to keep the men below. See, I’m sure few people think about these things when they see, in a movie, these beautiful ships under full sail and assume they’re as pristine as they appear!

Three Composers Fail in Their Master and Commander Score

With so many excellent film scores still bright in the memory, i.e., Bronislau Kaper’s Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), Philip Sainton’s Moby Dick, even Clifton Parker’s Treasure Island and best of all Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Captain Blood and The Sea Hawk, it’s perhaps surprising and unfortunate—no, no “perhaps” about it!—that the Crowe film has such a weak score, compared with its otherwise superb components. What “original” music there is does little to set the mood or move the film along.

It took three composers to assemble this embarrassment: Christopher Gordon, Iva Davies and Richard Tognetti. There’s much da-dum-te-dum and a lot of drum whacking for the action scenes, primarily the two battles, and much of what’s in between seems awash in murky nothingness. To go with the blue-steel visuals? No, I think not, more like weak pen and ink. Back in the Dark Ages of movie criticism, it used to be a viable thesis that “the best score is one you don’t notice”; well, this is the ultimate score not to notice!

What good music there is comes from composers who had no choice in participating in this project—Mozart, Boccherini and Bach. Aubrey and Maturin play cello-violin duets in several scenes, Crowe doing a fair job mimicking a violinist. One night scene, viewed from the stern of the ship, shows the two men through the great cabin windows; it is accompanied by the Prelude to Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G, BWV 1007. Substituting Korngold’s rich horns and lush strings, it could have been Captain Blood, with Peter Blood, at his own casement, telescope in hand, staring after a distant ship. “Sail on, little ship,” he says, “back to England, where we may never go.”

What good music there is comes from composers who had no choice in participating in this project—Mozart, Boccherini and Bach. Aubrey and Maturin play cello-violin duets in several scenes, Crowe doing a fair job mimicking a violinist. One night scene, viewed from the stern of the ship, shows the two men through the great cabin windows; it is accompanied by the Prelude to Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G, BWV 1007. Substituting Korngold’s rich horns and lush strings, it could have been Captain Blood, with Peter Blood, at his own casement, telescope in hand, staring after a distant ship. “Sail on, little ship,” he says, “back to England, where we may never go.”

It’s amazing how the eviscerated bits of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Fantasy on a Theme of Thomas Tallis fit so poignantly the loss of a sailor overboard, with Aubrey’s despair in cutting the last shroud that binds the sailor to the ship, and, later, the sea burial after the final battle with the Acheron, the bodies being sewn into their hammocks. These are the best parts of the “score.” It’s as if some master composer had slipped in among the persistent banalities and, twice and only twice in the entire film, captured the milieu of the screen. Someone—I’ve never been able to discover the source—has referred to this English masterpiece as having the shimmer of stained glass windows—and, for me, a mystic spirituality as well.

“Something Prickly and Hard to Eradicate”

Master and Commander has more technical blunders than three or four pictures combined, particularly because there are so many historical and nautical traps. And after centuries of sea saga writing and filming, it’s hard to avoid the usual clichés, of which there are numerous examples: the storm at sea (usually, as here, a trip ’round the Horn), the flogging (at least one!), a bloody operation, a contact with natives, insolent sailors toward command, bad rations, a ship feigning distress, the lost sailor overboard, captain having to prove he’s a navigating genius, longboats towing the ship, etc.

Master and Commander has more technical blunders than three or four pictures combined, particularly because there are so many historical and nautical traps. And after centuries of sea saga writing and filming, it’s hard to avoid the usual clichés, of which there are numerous examples: the storm at sea (usually, as here, a trip ’round the Horn), the flogging (at least one!), a bloody operation, a contact with natives, insolent sailors toward command, bad rations, a ship feigning distress, the lost sailor overboard, captain having to prove he’s a navigating genius, longboats towing the ship, etc.

The end of Roy Adkins’ book does good service for the end of this discussion of Master and Commander, as Aubrey and his crew were only six months away from Trafalgar in the opening of the film: “With the developments in technology during the peace that followed Napoleon’s final defeat, battleships came to be powered by stream rather than wind . . . and within sixty years the first iron battleship was launched . . . and so Trafalgar also proved to be the last major battle fought by sailing ships.”

But, on the other hand, maybe this dynamic Captain Jack Aubrey character, contradictions and all, should have the last words. He has changed his strategy and taken his friend the surgeon off the pitching and rolling Surprise to the solid, steady land of the Galápagos Islands for a necessary operation—one, as it proves, Maturin performs himself. When the surgeon confesses a gratitude he cannot possibly repay, Aubrey replies, “Name a shrub after me, something prickly and hard to eradicate.”