“Oh, I still do believe in God, old man. I believe in God and Mercy and all that. But the dead are happier dead. They don’t miss much here, poor devils.”— Harry Lime to Holly Martins

“Oh, I still do believe in God, old man. I believe in God and Mercy and all that. But the dead are happier dead. They don’t miss much here, poor devils.”— Harry Lime to Holly Martins

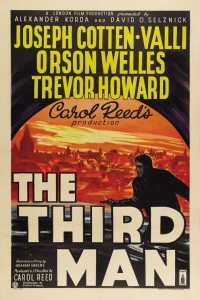

The Third Man. What, not remade yet? Not that I’m aware. One would think by now it would have been, the “logic” of film-making these days being what it is, for everything has to be remade, on the presumption of a “sure thing.” Remakes, much like sequels, are very rarely as good as their originals. Not even David O. Selznick, who was one of the producers, could mangle the film, though he tried. The Third Man wasn’t a film of his era, nor the kind he would have made and, not surprising, he didn’t really understand it.

Maybe because it was so good—is so good, because it continues to enthrall us—is the reason it hasn’t thus far been refilmed in some cataclysm of special effects (a Farris wheel that isn’t there), “much needed” action (maybe a few car chases), some “relevant” characters (a drug addict, a prostitute or two) or an “up-to-date” plot (maybe a serial killer). Don’t laugh! It’s very possible—someday—that these ideas will pop up in The Third Man II or The Fourth Man.

The Third Man was startlingly different in its day. Still is. The word “unique” can justly be applied to it. And why?— Because it is craftily directed by Carol Reed and generally well acted by all concerned. Cinematographer Robert Krasker, who had done Odd Man Out for Reed a few years before, renders some of the quirkiest camera angles—not always level, which helps unsettle the film—since Citizen Kane and shows, in brilliant, shadowy black and white, those Viennese cobblestone streets, squares, buildings and sewers. For the soundtrack there is the zither music of the then obscure Anton Karas, who afterward became famous. The zither only, no orchestra. Then there’s that enigmatic final shot. And, from his novel, Graham Greene wrote the screenplay.

The Third Man was startlingly different in its day. Still is. The word “unique” can justly be applied to it. And why?— Because it is craftily directed by Carol Reed and generally well acted by all concerned. Cinematographer Robert Krasker, who had done Odd Man Out for Reed a few years before, renders some of the quirkiest camera angles—not always level, which helps unsettle the film—since Citizen Kane and shows, in brilliant, shadowy black and white, those Viennese cobblestone streets, squares, buildings and sewers. For the soundtrack there is the zither music of the then obscure Anton Karas, who afterward became famous. The zither only, no orchestra. Then there’s that enigmatic final shot. And, from his novel, Graham Greene wrote the screenplay.

But not the most famous lines in the film, which were ad-libbed by Orson Welles on the spot, or so it goes: “Like the fella says, in Italy for thirty years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love. They had five hundred years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”

But not the most famous lines in the film, which were ad-libbed by Orson Welles on the spot, or so it goes: “Like the fella says, in Italy for thirty years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love. They had five hundred years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”

And, on top of these milestones, there is, almost an hour into the film, Welles’ nocturnal entrance, one of the most famous in movie history—in a doorway, in the shadows, with a cat gnawing his shoe laces. Untutored in the ways of human nature, the cat obviously doesn’t know the kind of guy it is cuddling.

(Small point: Ever since first seeing Welles’ introduction, I’ve always wondered why the camera, having followed the cat beside the wall, couldn’t have continued, without the cuts, directly to the feet, rather than showing the cat already there in a se parate shot. Temperamental cat, perhaps.)

parate shot. Temperamental cat, perhaps.)

It is post-World War II Vienna—very post-war, the winter of 1948-49 when the film was made—and there are bomb craters, stark walls of ruined buildings, curfewed streets, black marketeering and the four zones of occupation—British, American, French and Russian. No sets, the real Vienna the way it looked then.

Pulp Western writer Holly Martins (Joseph Cotton) has come to the scarred, suspicious city to look up an old buddy, Harry Lime (Welles), only to learn he was killed in a freak automobile accident. There are conflicting accounts from people who seem reluctant to talk. The undertow of animosity, emphasized in askew camera shots and fathomless shadows, is seen in unnaturally verbal children and in the intimidating stares of people, in dark doorways and from windows swung open.

Pulp Western writer Holly Martins (Joseph Cotton) has come to the scarred, suspicious city to look up an old buddy, Harry Lime (Welles), only to learn he was killed in a freak automobile accident. There are conflicting accounts from people who seem reluctant to talk. The undertow of animosity, emphasized in askew camera shots and fathomless shadows, is seen in unnaturally verbal children and in the intimidating stares of people, in dark doorways and from windows swung open.

In the mix are Lime’s girlfriend Anna (a beautiful but somewhat immobile-faced Italian actress, Alida Valli, whom Selznick had forced on Alfred Hitchcock for The Paradine Case) and Major Calloway (Trevor Howard), in charge of the British zone. Bernard Lee, of “M” fame from the future James Bond films, plays Calloway’s assistant.

Without knowing the nature of Martins’ novels, only that he’s read in Vienna, Mr. Crabbin (Wilfrid Hyde-White) invites Martins to speak at his literary organization. In one of the more humorous moments in the film, Martins is out of his depth when asked a learned question—“In which category do you place James Joyce?”—and the frustrated audience disperses as Crabbin announces an after-the-fact adjournment.

Without knowing the nature of Martins’ novels, only that he’s read in Vienna, Mr. Crabbin (Wilfrid Hyde-White) invites Martins to speak at his literary organization. In one of the more humorous moments in the film, Martins is out of his depth when asked a learned question—“In which category do you place James Joyce?”—and the frustrated audience disperses as Crabbin announces an after-the-fact adjournment.

An interesting footnote, the chases through the cavernous sewers of Vienna are reminiscent of the one—on a smaller scale, of course—in another film noir, He Walked by Night, premiered ten months earlier. Both have the echoing footsteps, the hollow voices and the saber-like swirl of the flashlights of men after a single quarry, and in both the pursued attempts an escape through a manhole. For Richard Basehart in He Walked by Night, a vehicle’s wheel on the manhole cover prevents his getaway. And Harry Lime, his nervous fingers wiggling through the holes like an upturned spider’s legs, is too weak to lift the grate.

And the last shot of the film? Originality itself. There’s a Vienna avenue of trees, disappearing in a distant perspective. According to Cotton’s autobiography, Vanity Will Get You Somewhere, the end of the film was undecided, the director not knowing how the novel ended. On location one day at a cemetery alongside this avenue where earlier scenes had taken place, Carol Reed suddenly announced, “Now we’ll shoot the ending.” No more said here about the actors, who have no dialogue, or what they do, as the stationary camera remains focused on the avenue for that final minute and ten seconds.

And the last shot of the film? Originality itself. There’s a Vienna avenue of trees, disappearing in a distant perspective. According to Cotton’s autobiography, Vanity Will Get You Somewhere, the end of the film was undecided, the director not knowing how the novel ended. On location one day at a cemetery alongside this avenue where earlier scenes had taken place, Carol Reed suddenly announced, “Now we’ll shoot the ending.” No more said here about the actors, who have no dialogue, or what they do, as the stationary camera remains focused on the avenue for that final minute and ten seconds.

Reed presumably didn’t have in mind the painting of a similar avenue of trees, this one in the country, by the 17th-century Dutchman Meindert Hobbema, “The Avenue at Middelharnis.” Hanging on a wall in my grandmother’s house—this in childhood, long before I had ever heard of The Third Man—was a large black and white copy of this painting.

In the face of all the originality and uniqueness of this film, a producer or director would be crazy, as well as foolhardy, to have a go at a remake. But, then, Hollywood has no respect for its masterpieces, and some of us wait with nervous foreboding.

Just a minor thing about the unanswerable questions fired at Martins as he struggles to get through the literary meeting: I’m fairly sure that the

‘Joyce’ question is: “where would you put James Joyce?”.

Joyce? Put him in Sylvia’s “Shakespeare and Company”!