“In Hollywood vernacular, I could write commercial.” — Dimitri Tiomkin

“In Hollywood vernacular, I could write commercial.” — Dimitri Tiomkin

There were—are, for their music endures, persists vividly in the present tense—what could be called “The Magnificent Seven” of Hollywood’s Golden Age film composers, who reigned supreme in the 1930s and ’40s: Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Franz Waxman, Max Steiner, Miklós Rózsa, Dimitri Tiomkin, Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Newman. The first three were—er, are—Austro-German, the fourth Hungarian, the fifth Russian, the last two, of all things!, American.

The names are arranged, basically, in order of musical merit, first to last. Korngold, Waxman, Rózsa and Herrmann, especially, also composed so-called “serious” music, to varying degrees of success, Korngold being a genius set apart. Herrmann, placed in the list to keep the Americans together, actually ranks considerably higher, possibly after Waxman as a film composer, for his style, besides being one of the most recognizable of the seven, is of surprising originality, if not variety. Steiner, if the truth be known, would follow Rózsa in musical stature. And Newman often supervised a team of composers and orchestrators, and thus many of “his” films lack a direct input, his personal touch.

The obvious composer omission, whose inclusion would have made the epithet, oddly, “The Magnificent Eight,” is Victor Young. True, he deserves to be on the list, if only because he is one of the great melodists of Hollywood. Remember “Stella by Starlight,” “When I Fall in Love,” “My Foolish Heart” and “Around the World in Eighty Days”? The temptation is to list other songs, for they are numerous—and memorable. But besides music he had other, strong conflicting “interests,” i.e., drinking and the ladies, and was not an especially conscientious artist. The line has to be drawn somewhere, and for his absence an apology is extended.

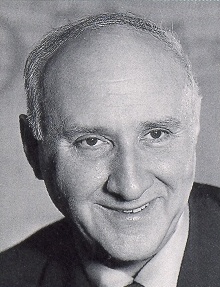

And Tiomkin? Like Young and Herrmann, Herrmann for his legendary bad manners and eccentricity, Tiomkin was in many respects a man unto himself—refreshingly unpretentious and gregarious, good to have at a party (or on the Jack Benny program in 1961!), adamant in what he thought right for a score yet willing to borrow a tune if it could prove useful, lacking Waxman’s Teutonic seriousness and Korngold’s need for perfect orchestration, devoid of any notion that his art was somehow sacred or “for the ages,” often making fun of his craft and himself.

And Tiomkin? Like Young and Herrmann, Herrmann for his legendary bad manners and eccentricity, Tiomkin was in many respects a man unto himself—refreshingly unpretentious and gregarious, good to have at a party (or on the Jack Benny program in 1961!), adamant in what he thought right for a score yet willing to borrow a tune if it could prove useful, lacking Waxman’s Teutonic seriousness and Korngold’s need for perfect orchestration, devoid of any notion that his art was somehow sacred or “for the ages,” often making fun of his craft and himself.

Also, like Young, he was a born melodist.

Compared with, say, Steiner’s or Herrmann’s or Newman’s style, Tiomkin’s is somewhat difficult to describe, though, more important, easy to recognize. For Korngold, an obvious stylistic clue is the opulent orchestration, for Herrmann, the dark, lower instrument motifs, for Rózsa, the inevitable play of horns against strings in practically every main title he wrote. Tiomkin likes available a large orchestra, a lot of percussion and, frequently, a chorus, but, above all, he has a penchant for singable melodies and catchy rhythms. Those staccato rhythms which he loved so are appropriate for the Westerns—for trotting, cantering or galloping horses, stagecoaches and carriages, Indians on the warpath, steaming locomotives, cattle drives and stampedes.

Different from the chameleon-like Herrmann who varies his instrumental palette for each film, Tiomkin is similar to Korngold or Steiner: the orchestral makeup remains essentially the same, picture-to-picture. Korngold, who at the beginning of his career had only a rudimentary grasp of the English language, gave the main title of Kings Row an heroic pageantry because he thought the picture was about kings, not tortured lives in a small American town. The main title remained unchanged and no one was the wiser.

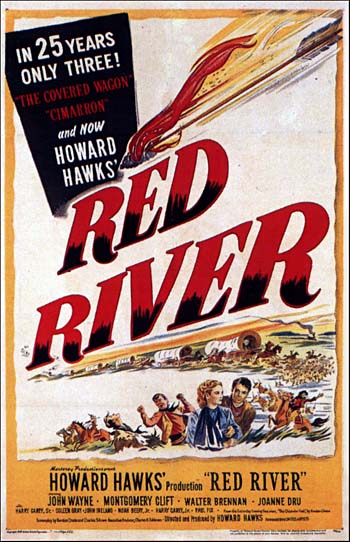

Likewise, Tiomkin’s brusque “walking” motif representing Bruno (Robert Walker) in the opening of Strangers on a Train could have been substituted, no incongruity felt, for the march-like swagger in Red River when Dunson (John Wayne) and Matt (Montgomery Clift) have their final confrontation. As a point of possible interest, it’s been suggested that the source of this Red River moment could have been a part of the middle section of Edward Elgar’s In the South Concert Overture of 1903.

Likewise, Tiomkin’s brusque “walking” motif representing Bruno (Robert Walker) in the opening of Strangers on a Train could have been substituted, no incongruity felt, for the march-like swagger in Red River when Dunson (John Wayne) and Matt (Montgomery Clift) have their final confrontation. As a point of possible interest, it’s been suggested that the source of this Red River moment could have been a part of the middle section of Edward Elgar’s In the South Concert Overture of 1903.

Dimitri Tiomkin had been places, knew the “biggies” and kept good company. A student at the music conservatory in St. Petersburg, he moved there, along with his family, soon after his birth in 1894 in Kremenchuk, the Poltava province of the Ukraine. He received instruction from Alexander Glazunov, a traditional, romantic composer who disavowed the atonal trends of the early twentieth century and who perhaps influenced his pupil toward similar thinking, since Tiomkin never aspired to write in the new ways.

Something of a prodigy, he concentrated on piano instruction at the conservatory and later made his début with the Berlin Philharmonic, appearing frequently with that orchestra. He knew Shostakovich and Prokofiev.

He gave the French première of Gershwin’s Concerto in F. Arriving in America in 1925, he wrote ballet sequences for four mediocre M-G-M movies. His first “real” film score was Resurrection (1931), appropriately set in Russia, but his inexperience with the English language and a disenchantment with Hollywood sent him to New York and Broadway. After the failure of his own play, Keeping Expenses Down, he returned to the West Coast.

Again, things went along unspectacularly until, in 1937, he worked for the first time with one of several important directors who would brighten his career over the years. He scored Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon, complete with a large orchestra and chorus, followed by the director’s You Can’t Take It with You, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Meet John Doe. Six years later, with It’s a Wonderful Life, their friendship ended over Tiomkin’s too “dark” a score; in fact, the eerie and horrific images—the graveyard scene and James Stewart’s near-madness, for example—contain some of the best music in the film.

Again, things went along unspectacularly until, in 1937, he worked for the first time with one of several important directors who would brighten his career over the years. He scored Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon, complete with a large orchestra and chorus, followed by the director’s You Can’t Take It with You, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Meet John Doe. Six years later, with It’s a Wonderful Life, their friendship ended over Tiomkin’s too “dark” a score; in fact, the eerie and horrific images—the graveyard scene and James Stewart’s near-madness, for example—contain some of the best music in the film.

In 1940, his first Western score, for The Westerner, went seemingly unnoticed, without fanfare, without an awareness of its portent. Nothing little about the movie, though: it was directed by William Wyler and starred Gary Cooper, and was good enough a film to receive two Oscar nominations and a win for Walter Brennan as Judge Roy Bean. The Wyler-Cooper-Tiomkin team would be reunited for Friendly Persuasion sixteen years later.

Eight of so movies after The Westerner, Tiomkin scored Shadow of a Doubt (1942), the first of four for another inspired director, a rotund fellow named Alfred Hitchcock. (Tiomkin was somewhat rotund himself, apple-shaped whereas Hitch was more like a pear.) Hitch, who was acutely aware of the importance of music in films, suggested Tiomkin base the Shadow score on Franz Lehár’s famous waltz from The Merry Widow to represent the charming menace of Joseph Cotton’s “Merry Widow” murderer. Sure, Tiomkin had borrowed before—“Polly Wolly Doodle” in You Can’t Take It with You and numerous tunes in Meet John Doe, including “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” among others. Plagiarizing music was common practice in those days, still is.

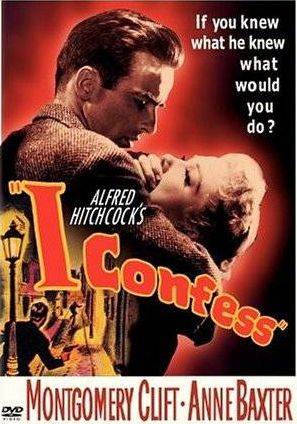

The other Hitch movies to follow, after a nine-year break, were Strangers on a Train, I Confess, which Tiomkin “confessed” was one of his favorite scores, and Dial M for Murder. In Strangers, Tiomkin uses turn-of-the-twentieth-century popular tunes during the carnival scenes, including “The Band Played On” for the famous merry-go-round crash. Besides the appearance of the liturgical “Dies Irae” throughout I Confess, Tiomkin and lyricist Ned Washington wrote the song, “Love, Look What You’ve Done to Me,” for the forbidden liaison between Father Logan (Montgomery Clift) and Ruth (Anne Baxter).

The other Hitch movies to follow, after a nine-year break, were Strangers on a Train, I Confess, which Tiomkin “confessed” was one of his favorite scores, and Dial M for Murder. In Strangers, Tiomkin uses turn-of-the-twentieth-century popular tunes during the carnival scenes, including “The Band Played On” for the famous merry-go-round crash. Besides the appearance of the liturgical “Dies Irae” throughout I Confess, Tiomkin and lyricist Ned Washington wrote the song, “Love, Look What You’ve Done to Me,” for the forbidden liaison between Father Logan (Montgomery Clift) and Ruth (Anne Baxter).

In Dial M for Murder, Tiomkin perhaps calls upon his Russian heritage, and what was, for him, most familiar music, the “Coronation Scene” from Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, at least a variation on it. This cue is played as Ray Milland and the would-be murderer (Anthony Dawson) check their watches for the crucial moment when Milland dials the number whose ringing will draw his wife (Grace Kelly) to the phone—and into the strangle hold of her killer.

Hitch was never fully satisfied with Tiomkin, nor with a number of his other composers. It wasn’t until the year after Dial that he found the ideal partner in Bernard Herrmann, beginning with The Trouble with Harry (1955), the first of eight films, the most productive director-composer collaboration until the team of Steven Spielberg and John Williams. Williams, ironically, scored Hitch’s last film, Family Plot in 1976.

All right, what had happened in Tiomkin’s career during this time, between the first and last of the Hitch films, between 1942 and 1954? Something of a milestone. He had begun scoring his first sets of Westerns. Now he was noticed, and if there wasn’t necessarily a fanfare as such, he was quickly typecast—wonderfully, as it turned out—as the composer for the film genre that would become his signature, in the way that Korngold is known for swashbucklers, Steiner for Bette Davis tear-jerkers, Herrmann for suspense and fantasy and Ron Goodwin for World War II films.

All right, what had happened in Tiomkin’s career during this time, between the first and last of the Hitch films, between 1942 and 1954? Something of a milestone. He had begun scoring his first sets of Westerns. Now he was noticed, and if there wasn’t necessarily a fanfare as such, he was quickly typecast—wonderfully, as it turned out—as the composer for the film genre that would become his signature, in the way that Korngold is known for swashbucklers, Steiner for Bette Davis tear-jerkers, Herrmann for suspense and fantasy and Ron Goodwin for World War II films.

During this period, Tiomkin wrote three of his most famous Westerns—Duel in the Sun (1946), Red River (1948) and High Noon (1952). The main theme of Red River—such a good tune—reappeared eleven years later in another Howard Hawks film, Rio Bravo, becoming a song, set to lyrics by Paul Francis Webster, “My Rifle, My Pony and Me,” and sung by Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson.

Two of these films provide famous, retellable incidents. Hollywood stories are, of course, endless—and their authenticity often dubious, so strange are the tales, the sayings, the gossip, the rumors. In this case, the story is true. David O. Selznick, the most critical of producers, gave Tiomkin endless trouble regarding Duel, disapproving of this and that. To reinforce the love/hate relationship between Lewton (Gregory Peck) and Pearl (Jennifer Jones), Selznick instructed his composer on the four ideas he wanted reflected in the score: jealousy, flirtation, sentiment and orgasm.

Two of these films provide famous, retellable incidents. Hollywood stories are, of course, endless—and their authenticity often dubious, so strange are the tales, the sayings, the gossip, the rumors. In this case, the story is true. David O. Selznick, the most critical of producers, gave Tiomkin endless trouble regarding Duel, disapproving of this and that. To reinforce the love/hate relationship between Lewton (Gregory Peck) and Pearl (Jennifer Jones), Selznick instructed his composer on the four ideas he wanted reflected in the score: jealousy, flirtation, sentiment and orgasm.

When Tiomkin played the four representations on the piano, the first three were approved. But, no, Selznick felt orgasm needed to be “throbbing” and “unbridled.” When the composer returned with another version, it still wasn’t right. A third try—no better. “Dimi,” Selznick counseled, “what we must have here is love-making music, and this isn’t the way I make love.” By now angry, Tiomkin shouted, “Look, Selznick, I don’t know how you make love, but this is how I make love.” Selznick, seeing the humor in it all, accepted the third version of orgasm.

When Tiomkin played the four representations on the piano, the first three were approved. But, no, Selznick felt orgasm needed to be “throbbing” and “unbridled.” When the composer returned with another version, it still wasn’t right. A third try—no better. “Dimi,” Selznick counseled, “what we must have here is love-making music, and this isn’t the way I make love.” By now angry, Tiomkin shouted, “Look, Selznick, I don’t know how you make love, but this is how I make love.” Selznick, seeing the humor in it all, accepted the third version of orgasm.

Also true is the story that High Noon received a terrible response at its pre-release preview until saved by the addition of Tiomkin’s score and the song “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh, My Darlin’.” With words by Ned Washington, Tiomkin’s most frequent lyricist, Tex Ritter sings behind the main title and throughout the film, a kind of troubadour in a medieval morality play. Here is one of the best examples of a movie being greatly improved by its score…

The music in “The Clock and Showdown” sequence tightens the scenes—clearly heightens the suspense—just before the arrival of the train bringing the last of the four gunmen who seek revenge on Marshall Kane (Gary Cooper). In essence, this music is a set of variations on the inner part of the melody supporting the words, “O to be torn ’twixt love and duty.” Apart from viewing the movie itself, this sequence can best be appreciated in the Unicorn-Kanchana recording, a compilation titled “The Western Film World of Dimitri Tiomkin,” with Laurie Johnson and the London Studio Symphony.

This technique of a “title song,” as it was soon called, became a vogue, up to the point where every picture had to have a title song. The device nearly wrecked—no, did wreck for a while!—not only many movies but the art of film scoring. In fact, in the case of many movies, a “score”—hardly the proper word—was nothing more than a string of “pop” or rock songs.

Not until John Williams’ score for Star Wars (1977) did the old-fashioned, wall-to-wall orchestral score, à la Korngold and Steiner, brilliant and sharing equal importance with the image on screen, officially reassert itself. Thankfully. Not to say there hadn’t been positive “rebellion” earlier—Richard Rodney Bennett’s Murder on the Orient Express in 1974, and any number of scores by, most notably, Jerry Goldsmith and Elmer Bernstein, who did their best to keep alive the old craft.

A list of just the Westerns Tiomkin scored from 1954 to 1960 would comprise The Command, A Bullet Is Waiting, Strange Lady in Town, Friendly Persuasion, Tension at Table Rock, Giant, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Night Passage, The Young Land, Wild Is the Wind, Rio Bravo, Last Train from Gun Hill, The Unforgiven, The Alamo and The Sundowners. Talk about being typecast!

In many of these films, in the manner of High Noon, a male singer croons the title song: “Thee I Love” (Pat Boone) in Friendly Persuasion, “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” (Frankie Laine) in Gunfight, “Follow the River” (James Stewart) in Night Passage and “Rio Bravo” (Dean Martin) in Rio Bravo.

The Westerns, of course, are an excellent place to experience a true musical picture of Tiomkin. For instance, the arrival of Davy Crockett (John Wayne) in The Alamo (1960) has a light, easy-going lilt; by contrast, the cattle raid is punctuated by those staccato rhythms that so fascinate. From Friendly Persuasion (1956), the “Thee I Love” tune, whether sung or in some orchestral trapping, is one of the composer’s more sentimental and all too many recording wring maximum schmaltzy from it. Tiomkin works the melody into just above every measure of the score, but the “Carriage Chase” is done with welcomed restraint. There are other effectively scored buggy rides—in Duel in the Sun and Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, to name only two.

The Westerns, of course, are an excellent place to experience a true musical picture of Tiomkin. For instance, the arrival of Davy Crockett (John Wayne) in The Alamo (1960) has a light, easy-going lilt; by contrast, the cattle raid is punctuated by those staccato rhythms that so fascinate. From Friendly Persuasion (1956), the “Thee I Love” tune, whether sung or in some orchestral trapping, is one of the composer’s more sentimental and all too many recording wring maximum schmaltzy from it. Tiomkin works the melody into just above every measure of the score, but the “Carriage Chase” is done with welcomed restraint. There are other effectively scored buggy rides—in Duel in the Sun and Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, to name only two.

Not to imply that Tiomkin couldn’t compose—and compose well—for other types of films. He could, as evident in the periodic appearance of salient movies that display a creative, fertile imagination in other directions. Portrait of Jennie (1949), although a failed picture, a signpost along Selznick’s road of decline, demonstrates what atmosphere and variety Tiomkin could fashion from someone else’s music, Debussy’s “Girl with the Flaxen Hair.” The next year, in Cyrano de Bergerac, which earned José Ferrer a Best Actor Oscar, Tiomkin evokes the musical spirit of mid-seventeenth-century France, à la Rameau and Lully, with, again, a large orchestra, now with a thirty-piece brass section.

Never in Tiomkin’s career, however, would there be such a drastic, dramatic contrast between the baroque flavor of Cyrano and the modern, atonal cacophony of The Thing (From Another World), which followed the next year. Not by any stretch of the imagination is it authentic atonal music, but a melodic composer’s notion of how the atonal might sound.

Never in Tiomkin’s career, however, would there be such a drastic, dramatic contrast between the baroque flavor of Cyrano and the modern, atonal cacophony of The Thing (From Another World), which followed the next year. Not by any stretch of the imagination is it authentic atonal music, but a melodic composer’s notion of how the atonal might sound.

As Royal S. Brown so aptly complained in 1977 in High Fidelity magazine, the Tiomkin installment of RCA’s mid-‘70s “Classic Film Score” series didn’t represent the composer’s best music. And what was among Tiomkin’s finest, a ten-minute suite from The Thing—in fact, recorded at the time of the initial album—was relegated, two years later, to an embarrassing “leftovers” LP. One side contained excerpts from previous releases (the old recycle ploy) in the series, the flip side music which didn’t fit on those albums.

An early career milestone is Lost Horizon (1937), an over-all excellent score, a strange mixture of the exotic and the spiritual. The music for the horseback ride of Conway (Ronald Colman) and Sondra (Jane Wyatt) through Shangri-La, when they become temporarily separated by a waterfall, is deftly scored, at times with quasi-Glazunov shimmer and lightness. And such lightness from an orchestra that is stacked to pack a wallop—and which does, on occasions—with a large and a colorful array of percussion, including five glockenspiels, four tuned Tibetan gongs, three tam-tams, numerous pairs of cymbals, xylophone, marimba, vibraphone and, of course, tubular bells, of which Tiomkin was very fond—three sets of them.

A small observation: With Tiomkin’s mass of instruments, much like all that percussion for the gold caravan trek in Korngold’s The Sea Hawk, it’s debatable how many of the nuances and timbres the audiences of the ’30s and ’40s could differentiate, with, by today’s standards, such primitive recording and playback systems!

Another significant individual who introduced Tiomkin to new material and fresh ways of thinking, writer-producer-director Carl Foreman (not to be confused with the later-generation Milos Forman) was responsible for more Tiomkin films, including Cyrano de Bergerac and High Noon, than either Capra, Hawks or Hitchcock. Their final collaboration was The Guns of Navarone (1961). Its main title (below) is Tiomkin at his resplendent best—alternately brassy, lyrical, syncopated, with staccato rhythms and tubular bells to boot, and all done with the simplest of material. In short, exciting. If an introduction to Tiomkin is sought by those unfamiliar with his music, here is the best place to start.

Although Tiomkin had won an Oscar for the score for The High and the Mighty (1954)—he had already won two previously, for score and song in High Noon—his vivid versatility shows again in The Old Man and the Sea (1958). Spencer Tracy is practically a one-man show, with help from someone unseen but definitely heard. The score adds so much to the movie and is, as film music authority Tony Thomas wrote, “ . . . the closest thing yet to a symphonic poem from the screen.” It was Tiomkin’s last Oscar.

After five Westerns in a row, in 1959 and 1960, he scored none for six years, and then his career slowed to one picture a year. His last Western was The War Wagon (1967), with John Wayne and Kirk Douglas. The song, “Ballad of the War Wagon,” again with lyrics by Ned Washington, is not especially noteworthy, the score sparse and without the Dimitri panache. It’s another instance, possibly, of his casual approach to certain pictures, or the score might have been a casualty of its time. Maybe someone whispered, “Not too much music now, Dimitri.”

At the other extreme was his intense devotion to other films, such as Great Catherine (1968), for which he thought he should have been nominated. He was nominated, though, for his last score, Tchaikovsky. He had, in a sense, come full circle. Made in Russia in 1969, it was Tiomkin’s last Academy nomination, the last of twenty-three since 1937! He lost to a Frenchman, Michel Legrand, for Summer of ’42.

There is one final tribute to the Tiomkin humor—or so it’s assumed he meant to be humorous at the 1954 Academy Award ceremonies when he received that Oscar for The High and the Mighty. His acceptance speech began, “I would like to thank Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, Strauss, Rimsky-Korsakov . . . ,” but the rest was drowned out by rollicking laughter. Was he being funny—or serious, acknowledging the centuries-long contributions classical composers had made to music? Yes, some people congratulated Tiomkin on his wit, others—fellow composers—ridiculed his criticism of their profession.

There is one final tribute to the Tiomkin humor—or so it’s assumed he meant to be humorous at the 1954 Academy Award ceremonies when he received that Oscar for The High and the Mighty. His acceptance speech began, “I would like to thank Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, Strauss, Rimsky-Korsakov . . . ,” but the rest was drowned out by rollicking laughter. Was he being funny—or serious, acknowledging the centuries-long contributions classical composers had made to music? Yes, some people congratulated Tiomkin on his wit, others—fellow composers—ridiculed his criticism of their profession.

.