Some of the murders perfectly reflect their Shakespearean sources. The answers to the three questions I asked earlier are ideal examples. Like all the other victims who fall foolishly into the traps, their egos and vanity causing their downfall, Oliver Larding (Coote) arrives at what he believes to be a wine tasting party. He is forthwith drowned in a barrel of wine, with Lionheart, costumed as Richard III, quoting the proper lines as the hunchback king. You see, Richard III is classified as a history, but, like so much in Shakespeare, it has it’s . . . er . . . tragic moments—and does it!

Even police security cannot save another critic, Meredith Merridew (Morley), when he arrives incommunicado at his own home, police standing guard. His two pet poodles, always his constant companions, don’t come when they’re called, but Merridew is easily distracted, gullibly flattered to find, behind a pulled-back curtain, that he’s a surprise guest on the TV program “This Is Your Dish.” That trademark vanity, perhaps characteristic of so many critics, is reflected in his concern for which camera is aimed at him.

Lionheart is here disguised, not as Titus of the play, “Rome’s best champion,” but as a French chef who serves Merridew an absolutely sumptuous meat pie. In Titus Andronicus, Titus bakes the flesh of two of Queen Tamora’s sons in a pie. So Lionheart has baked—yes, you guessed it! Lionheart force-feeds Merridew the pie with a funnel and stomper until, wide-eyed, the critic expires on the dining room table. “Pity,” Lionheart calmly observes. “He didn’t have the stomach for it.” No, not Shakespeare, but the Bard did say, in Henry V, “He hath no stomach for this fight,” part of Henry’s great St. Crispin’s Day speech that includes “we band of brothers.”

Lionheart is here disguised, not as Titus of the play, “Rome’s best champion,” but as a French chef who serves Merridew an absolutely sumptuous meat pie. In Titus Andronicus, Titus bakes the flesh of two of Queen Tamora’s sons in a pie. So Lionheart has baked—yes, you guessed it! Lionheart force-feeds Merridew the pie with a funnel and stomper until, wide-eyed, the critic expires on the dining room table. “Pity,” Lionheart calmly observes. “He didn’t have the stomach for it.” No, not Shakespeare, but the Bard did say, in Henry V, “He hath no stomach for this fight,” part of Henry’s great St. Crispin’s Day speech that includes “we band of brothers.”

The old rake Trevor Dickman (Andrews) is lured by a seductive Edwina to the deserted theater which Lionheart makes his home—and stage for several of his deadly re-enactments. With Lionheart as Shylock quoting lines from The Merchant of Venice, old Trevor must yield a pound of his flesh, one of the bloodier vignettes in the film. No, no, that’s wrong: all the vignettes are bloody! Unlike the play, where Shylock is legally prohibited from taking that pound of flesh, Lionheart does the deed—and a pound not “closest to his heart” but the heart itself. The organ is sent to the Critic’s Circle, nicely boxed and neatly wrapped, with a note “from” Dickman: “I’m sorry to have missed the meeting, but my heart is with you.”

Some of the murders require a stretch to connect with their Shakespearean models. The smoldering, sparking electrocution of Miss Moon (Browne) under a hair dryer has a distant link to Joan of Arc’s burning at the stake in Henry VI: Part I. For Othello, Lionheart tricks Solomon Psaltery (Hawkins) into believing his wife (Diana Dors) is unfaithful. So, like the Moor’s treatment of Desdemona, he smothers his wife in bed. A slight deviation here: Othello, as you know, stabs himself and quickly dies at play’s end, while Psaltery earns life in prison. Lionheart engages Peregrine Devlin (Hendry) in a duel, doubling Romeo and Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet, although in the original stage version, probably around 1597, I don’t recall the combatants springing from trampolines!

Some of the murders require a stretch to connect with their Shakespearean models. The smoldering, sparking electrocution of Miss Moon (Browne) under a hair dryer has a distant link to Joan of Arc’s burning at the stake in Henry VI: Part I. For Othello, Lionheart tricks Solomon Psaltery (Hawkins) into believing his wife (Diana Dors) is unfaithful. So, like the Moor’s treatment of Desdemona, he smothers his wife in bed. A slight deviation here: Othello, as you know, stabs himself and quickly dies at play’s end, while Psaltery earns life in prison. Lionheart engages Peregrine Devlin (Hendry) in a duel, doubling Romeo and Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet, although in the original stage version, probably around 1597, I don’t recall the combatants springing from trampolines!

Theater of Blood doesn’t always know what it wants to be. At times, as in the decapitation of Horace Sprout (Lowe), it’s either slapstick or pseudo drama, with Lionheart acting the role of a surgeon. Michael J. Lewis’ score is neither comic, dramatic nor horrific but diametrically light and lyrical, à la John Barry in a romantic mood. (I’m thinking of They Might Be Giants.) Joan Hickson, the future BBC Miss Marple, plays Sprout’s bossy wife, with the maid doing a pratfall right out of the Three Stooges. Incidentally, the Shakespearean connection here is Cymbeline, listed as a comedy, but with the beheading of a queen’s son, Cloten, the play sure seems like a tragedy.

By contrast, the demise of Hector Snipe (Price) is played straight, the atmosphere treated ominously, the music alternately eerie, nervous or portentous. Price is quite good at conveying his changing reactions, first flattered by Lionheart’s faint praise, then worrisomely suspicious when the actor turns nasty, then relieved by stagehands who assure him he is “among friends,” then, finally, when it’s too late, terrified by what is about to happen to him. Lionheart, now dressed as Achilles, shouts, “The dragon wing of night o’erspreads the earth,” and thrusts a spear through Snipe’s body. The funeral of the previous victim, Maxwell, is interrupted by a galloping horse, dragging, tied to its tail, the disfigured body of Snipe. Thus the re-enactment of the fate of Hector in Troilus and Cressida is complete.

By contrast, the demise of Hector Snipe (Price) is played straight, the atmosphere treated ominously, the music alternately eerie, nervous or portentous. Price is quite good at conveying his changing reactions, first flattered by Lionheart’s faint praise, then worrisomely suspicious when the actor turns nasty, then relieved by stagehands who assure him he is “among friends,” then, finally, when it’s too late, terrified by what is about to happen to him. Lionheart, now dressed as Achilles, shouts, “The dragon wing of night o’erspreads the earth,” and thrusts a spear through Snipe’s body. The funeral of the previous victim, Maxwell, is interrupted by a galloping horse, dragging, tied to its tail, the disfigured body of Snipe. Thus the re-enactment of the fate of Hector in Troilus and Cressida is complete.

This, you see, is the incongruity of the film. Except for those moments of civility and apparent seriousness, there are others just as extreme in the other direction—the comic and slapstick. And yet the unnecessary bloodiness and graphic nature of the slayings seem to fit neither straight drama nor burlesque humor. Many viewers, even almost forty years after the film was made, will be turned off by the repellent scenes of death.

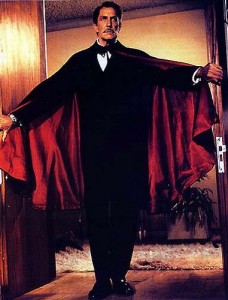

Vincent Price, as usual in these types of films, plays his various roles to the full, even showing a refined nuance on occasions and what might be seen, in this context, as undue restraint. He does ham it up at times, for, after all, that’s his character here. One can sense, though, that just beneath the surface, the actor has his tongue in his cheek, and his good fun clearly spreads to other members of the cast. “During the course of [Theater of Blood],” Price once said, “I play scenes from a number of Shakespearean plays. A feast for any actor!” And a feast it is for Price, who died in 1993. His last theatrical movie appearance was as the inventor in Edward Scissorhands with Johnny Depp.

Vincent Price, as usual in these types of films, plays his various roles to the full, even showing a refined nuance on occasions and what might be seen, in this context, as undue restraint. He does ham it up at times, for, after all, that’s his character here. One can sense, though, that just beneath the surface, the actor has his tongue in his cheek, and his good fun clearly spreads to other members of the cast. “During the course of [Theater of Blood],” Price once said, “I play scenes from a number of Shakespearean plays. A feast for any actor!” And a feast it is for Price, who died in 1993. His last theatrical movie appearance was as the inventor in Edward Scissorhands with Johnny Depp.

Price began his early creative life as a serious stage actor, starring as Prince Albert opposite Helen Hayes in Victoria Regina, later in Charley’s Aunt, Outward Bound and, yes, even in Shakespeare—as the Duke of Buckingham in Richard III. But, lest we forget, Price’s pedigree is often overlooked: a graduate of Yale and the University of London, author of cook books, an art authority and PBS television host. Like Boris Karloff, a ghoulish screen persona contradicted an erudite and sophisticated reality.

So, from all this, for his ultimate claim to fame, it seems Price had “descended” to horror film actor. Not at all. He thoroughly enjoyed his life, in all its aspects. Years before his death, he said, “I love to act. Making these horror films is a marvelous experience for me, especially when they’re so different and creative . . . It’s becoming harder and harder to scare people. We still rely on the basic elements of fear: snakes, rats, claustrophobia. But we’re adding all the time. I must say I’ve had a lot of fun with it all.”

So, from all this, for his ultimate claim to fame, it seems Price had “descended” to horror film actor. Not at all. He thoroughly enjoyed his life, in all its aspects. Years before his death, he said, “I love to act. Making these horror films is a marvelous experience for me, especially when they’re so different and creative . . . It’s becoming harder and harder to scare people. We still rely on the basic elements of fear: snakes, rats, claustrophobia. But we’re adding all the time. I must say I’ve had a lot of fun with it all.”