Aunt Lavinia wails, “Can you be so cruel?” Catherine doesn’t hesitate: “Yes, I can be very cruel. I have been taught—by masters.” She closes the drapes, resumes her latest embroidery, “For I shall never do another,” she says.

After Lavinia has left, there is the expected jingle of the doorbell. The house servant Maria (Vanessa Brown) comes to open the door and Catherine instructs her to bolt it. As the clock chimes as it had for that previous rendezvous, she finishes the embroidery, hesitating before snipping the last thread. To the accompaniment of Morris’ knocking, she extinguishes a lamp, takes a second one and slowly ascends the stairs, the shadows from the light moving slowly through the glass transom of the front door. Townsend now beats on the door, then shouts, over and over, “Catherine! Catherine!”

After Lavinia has left, there is the expected jingle of the doorbell. The house servant Maria (Vanessa Brown) comes to open the door and Catherine instructs her to bolt it. As the clock chimes as it had for that previous rendezvous, she finishes the embroidery, hesitating before snipping the last thread. To the accompaniment of Morris’ knocking, she extinguishes a lamp, takes a second one and slowly ascends the stairs, the shadows from the light moving slowly through the glass transom of the front door. Townsend now beats on the door, then shouts, over and over, “Catherine! Catherine!”

Speaking of Montgomery Clift, to my mind at least, his performance is the least impressive of the three, top-billed stars. As a temperamental, eccentric actor who deferred to his female acting coach instead of to director Wyler, a habit that would cause epic distress for John Huston during Freud, Clift is less remarkable than the young Olivia whose acting abilities he disparaged. He wasn’t nominated for a Best Acting Oscar, and justly so, I think. He seems just a little wooden and, in his physical presence, too “modern,” much as in Red River, his second-ever feature, where he doesn’t seem dusty or bedraggled enough to be a genuine cowboy.

Personally, I never tire of watching Sir Ralph Richardson do his magic; how he handles the spoken word carries weight in itself. His best work emerges irrespective of film genre or time setting. He is in great form in productions as diverse as Long Day’s Journey into Night, Laurence Olivier’s Richard III (as the Duke of Buckingham), Anna Karenina (1948) and The Four Feathers. A personal favorite—hardly a good film, though Ralph triumphs over the material—is Woman of Straw. The actor plays an old, egotistical and invalid rich man who marries a young woman (Gina Lolobrigida), in cahoots with Sean Connery to kill him for his money, with Connery double-crossing Lolobrigida.

Personally, I never tire of watching Sir Ralph Richardson do his magic; how he handles the spoken word carries weight in itself. His best work emerges irrespective of film genre or time setting. He is in great form in productions as diverse as Long Day’s Journey into Night, Laurence Olivier’s Richard III (as the Duke of Buckingham), Anna Karenina (1948) and The Four Feathers. A personal favorite—hardly a good film, though Ralph triumphs over the material—is Woman of Straw. The actor plays an old, egotistical and invalid rich man who marries a young woman (Gina Lolobrigida), in cahoots with Sean Connery to kill him for his money, with Connery double-crossing Lolobrigida.

The ugliness of Richardson’s character in Woman of Straw might be close to Olivia’s description of his behavior in The Heiress, the “wicked, selfish man” who stole scenes from her. One such scene possibly reinforces her complaint: when she is rewriting her father’s will, Richardson rests his right arm on the desk in front of her and continually moves his hand, as if to draw attention to himself in a moment that belongs to her.

The Heiress, however, belongs to Olivia. It was the last of a series of four consecutive outstanding films between 1946 and 1949. The Dark Mirror, in 1946, was followed by To Each His Own, her first Oscar (third nomination), and The Snake Pit, earning her another nomination. Like so many other stars of her age and time, among them Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, Olivia turned for work to horror films, the best being Lady in a Cage and Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte, but, by contrast, The Screaming Woman (for TV) and The Swarm were painful descents into Grade B junk. Her last film—and that for TV—was made in 1984.

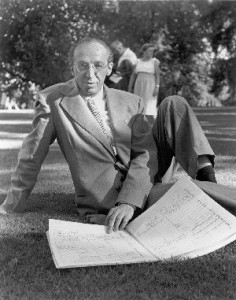

Another most important “player” in The Heiress is Aaron Copland’s score. It adds a deft touch, just enough comment—neither wall-to-wall (far from it), nor so sparing as to be irrelevant. Copland’s voice is heard when appropriate, when a romantic, ominous or dramatic touch is justified. There is that already discussed two-note declaration at the end of Catherine’s “You cheated me” speech. Although it may draw attention to itself, it is the perfect complement to what has preceded it on screen.

Another most important “player” in The Heiress is Aaron Copland’s score. It adds a deft touch, just enough comment—neither wall-to-wall (far from it), nor so sparing as to be irrelevant. Copland’s voice is heard when appropriate, when a romantic, ominous or dramatic touch is justified. There is that already discussed two-note declaration at the end of Catherine’s “You cheated me” speech. Although it may draw attention to itself, it is the perfect complement to what has preceded it on screen.

Copland’s tour de force, however, is the variety of musical images that accompany Catherine’s sequence of emotions as she awaits Morris’ arrival for their elopement—first, excitement at hearing a carriage that might be his, ponderings that she may never again stand at the window and “see Washington Square on a windy April night”; then, as the clock chimes the rendezvous hour and another carriage rattles by without stopping, the terrible suspicion that she might have been betrayed; and yet, more distraught, sitting beside her suitcases, hoping there’s still a chance, and pleading, “He must come, he must come.” Finally, with the realization that Morris is not coming, her scream is blended with the terrifying minor key howl of Copland’s orchestra.

After the composer had written his score, Wyler had the main title music changed—from Copland’s modern bite to a conventionally harmonic version of Jean Paul Martini’s French love song “Plaisir d’amour,” which Townsend plays on the piano and which Copland spots throughout the film. Although a Coplandesque flavor endures in the cadence of the main title, the composer wanted his name withdrawn from the credits, unsuccessfully as it turned out. Nonetheless, he won an Oscar for Best Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture, up against Dimitri Tiomkin’s Champion and Max Steiner’s Beyond the Forest—remember the chug-chug of the train in music, complete with whistle?

After the composer had written his score, Wyler had the main title music changed—from Copland’s modern bite to a conventionally harmonic version of Jean Paul Martini’s French love song “Plaisir d’amour,” which Townsend plays on the piano and which Copland spots throughout the film. Although a Coplandesque flavor endures in the cadence of the main title, the composer wanted his name withdrawn from the credits, unsuccessfully as it turned out. Nonetheless, he won an Oscar for Best Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture, up against Dimitri Tiomkin’s Champion and Max Steiner’s Beyond the Forest—remember the chug-chug of the train in music, complete with whistle?

For individuals wishing to hear the soundtrack apart from the film, there’s an excellent recording—though not itself perfect—with Leonard Slatkin conducting the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. The eight-minute Heiress suite of highlights isn’t pure Copland but “reconstructed” by Arnold Freed; it does include, however, a semblance of the composer’s original main title and sequences titled “Catherine’s Engagement,” “Cherry Red Dress,” “Departure,” “Morris Suggests Love,” “The Proposal” and that all-too-frequent ambiguous, catchall designation in film score recordings of “Finale,” whose final cadence is shorn of its original hammering chords.

Best of all, the CD contains Copland’s best film score, that for The Red Pony, in his familiar “Americana” style of Rodeo and Appalachian Spring.

A really good film on many levels. You’ve just got to admire Olivia de Havilland, she was never shy to tackle radical roles. This is true feminism if you like, though I prefer to look at it as a grand exploration of people’s relationships with one another. There is a real warmth to this film in a way that surprises me each time I see it.. I respect this movie so much.

When Morris jilts Catherine, she has to climb the stairs to her bedroom carrying the suitcase she had packed for their elopement. De Havilland did numerous takes, but was not able to reach to level of emotion that Wyler was looking for. Finally, she got so frustrated that the usually professional de Havilland threw the suitcase at him. At that point, Wyler realized the problem: there was nothing in the suitcase. He then ordered it filled with heavy props so that de Havilland’s efforts to drag it up the stairs perfectly captured her deep dejection.