Don’t Tell Anyone What Happened in the Summer House!

Don’t Tell Anyone What Happened in the Summer House!

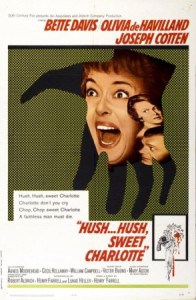

As late as it was in the careers of all three principals, it might be assumed that Hush . . . Hush, Sweet Charlotte was something of a reunion. It’s true that before 1964 Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland had made at least three films together, including The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex; Bette Davis and Joseph Cotton had been united in one earlier film, Beyond the Forest, which probably neither recalled with much pride; and Davis had appeared with Joan Crawford in Hollywood Canteen and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?

Joan Crawford? But that’s a fourth star? Joan Crawford originally had the part of Bette’s cousin in Hush . . . Hush, Sweet Charlotte, but was replaced by Olivia de Havilland due to illness, an illness that might or might not have been legitimate, depending on the source. The director Robert Aldrich had said she was “seriously sick. . . . Insurance companies here are terribly tough; there’s no such thing as a made-up ailment that they pay off on.” Then again, another director, Vincent Sherman, remembered that Joan told him in her hospital room, “I’m not sick. I just couldn’t stand working another minute with that Bette Davis.”

The Bette Davis – Joan Crawford feud had been on-going for many years. Curtis Bernhardt, not a “Bette Davis director” as such, though he did direct her in A Stolen Life and Payment on Demand, recalled that “[Joan Crawford] threw her handbag at me several times when . . . I called her Bette Davis by mistake. The chief difference between Joan Crawford and Bette Davis is that, while Bette Davis is an actress through and through, Joan Crawford is more a very talented motion picture star.”

If clearly not a reunion, the filming of Hush . . . Hush, Sweet Charlotte was “memorable”—notorious—for the demonstration of bad behavior on both Bette Davis’ and Joan Crawford’s parts. The two stars, on their own, could be quite professional, but not on this occasion. To show the pettiness that existed between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, in one scene Bette Davis arranged for a Coca-Cola truck to pass down the street, as Joan Crawford was then on the board of the Pepsi Company and had had Pepsi drink machines installed on the set.

If clearly not a reunion, the filming of Hush . . . Hush, Sweet Charlotte was “memorable”—notorious—for the demonstration of bad behavior on both Bette Davis’ and Joan Crawford’s parts. The two stars, on their own, could be quite professional, but not on this occasion. To show the pettiness that existed between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, in one scene Bette Davis arranged for a Coca-Cola truck to pass down the street, as Joan Crawford was then on the board of the Pepsi Company and had had Pepsi drink machines installed on the set.

Before Joan Crawford’s return from the hospital, as much filming as possible had been done around her. When Joan Crawford finally appeared before the cameras she was often too weak to work more than a few hours at a time, and it was finally decided she had to be replaced.

The selection of Olivia de Havilland—not the first choice—was even then temporarily tenuous, as Olivia, like Vivien Leigh and Loretta Young before her, liked neither the unsympathetic character nor appearing in a horror film. Aldrich flew to Switzerland where Olivia de Havilland was living at the time, relaying Bette Davis’ wish that she take the role. Olivia de Havilland accepted only when Aldrich agreed to a softening rewrite of her part.

Olivia de Havilland had just made the gory Lady in a Cage, part of her descent from her glory days of the late 1940s, so Hush . . . Hush, Sweet Charlotte wasn’t that abrupt a change. The film is Grand Guignol at its grandest—and Southern Gothic to boot! A long prologue from almost forty years earlier, in 1927, sets the tone. During a grand ball, a young Charlotte (Bette Davis) has a meeting with her married lover John Mayhew (Bruce Dern, who that same year had appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Marnie) in the summer house of her father’s columned Louisiana, plantation-style mansion. Cousin Miriam, resentful of Charlotte, had told the father, “Big Sam” (Victor Buono), of the affair, and the father had warned John that he would have neither his daughter nor his home.

Olivia de Havilland had just made the gory Lady in a Cage, part of her descent from her glory days of the late 1940s, so Hush . . . Hush, Sweet Charlotte wasn’t that abrupt a change. The film is Grand Guignol at its grandest—and Southern Gothic to boot! A long prologue from almost forty years earlier, in 1927, sets the tone. During a grand ball, a young Charlotte (Bette Davis) has a meeting with her married lover John Mayhew (Bruce Dern, who that same year had appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Marnie) in the summer house of her father’s columned Louisiana, plantation-style mansion. Cousin Miriam, resentful of Charlotte, had told the father, “Big Sam” (Victor Buono), of the affair, and the father had warned John that he would have neither his daughter nor his home.

Later, an unseen somebody—only an arm wielding a meat cleaver is seen—chops up Mayhew, separating his head and a hand, which are never found. A hush falls over the festivities as Charlotte (Bette Davis veiled and discreetly shot in heavy shadows or from behind) appears, dazed and in a blood-stained white dress.

It’s the present now. A group of ten-year-old boys approach the now decrepit mansion and dare a novice (John Megna, Dill in To Kill a Mockingbird two years earlier) to enter the shadowy house. He does, hesitantly, opening a music box, a gift from John. The boy is startled when Charlotte rises from a large high-back chair and flees the house.

After the opening credits and the title song, there’s the close-up of the blade (a far-fetched allusion to the cleaver?) and tracks of a noisy bulldozer. A crew of state workers are making way for a new highway—directly through Charlotte’s property, which she defends with a near-miss rifle shot at the driver. “If I’d been aimin’ to kill him, I would have!” The foreman (George Kennedy) angrily approaches the house and, from the balcony, Charlotte tips over an enormous concrete planter (quite a feat!), which crashes to the ground. The foreman orders his men to keep out of sight—temporarily, at least.

After the opening credits and the title song, there’s the close-up of the blade (a far-fetched allusion to the cleaver?) and tracks of a noisy bulldozer. A crew of state workers are making way for a new highway—directly through Charlotte’s property, which she defends with a near-miss rifle shot at the driver. “If I’d been aimin’ to kill him, I would have!” The foreman (George Kennedy) angrily approaches the house and, from the balcony, Charlotte tips over an enormous concrete planter (quite a feat!), which crashes to the ground. The foreman orders his men to keep out of sight—temporarily, at least.

Harry Willis (Cecil Kellaway), an insurance adjuster from London masquerading as a reporter, talks to the local sheriff (Wesley Addy) about the chances of meeting Jewel Mayhew (Mary Astor in her last screen appearance), widow of the murder victim. The sheriff relates the story of Charlotte, that any possible charges against her as John Mayhew’s murderer were never pursued, possibly owing to her father’s connections.

Cousin Miriam (de Havilland) soon arrives by taxi to assist Charlotte in moving, as the state plans to tear down the house for the highway. Attending Charlotte is Miriam’s former lover Dr. Drew Bayliss (Joseph Cotton), who jilted Miriam many years earlier.

Cousin Miriam (de Havilland) soon arrives by taxi to assist Charlotte in moving, as the state plans to tear down the house for the highway. Attending Charlotte is Miriam’s former lover Dr. Drew Bayliss (Joseph Cotton), who jilted Miriam many years earlier.

De Havilland plays well the part that was rewritten for her, that of polite Southern gentility, almost too well, as preciously subdued at times as Davis’ performance is often over the top. When Charlotte, who lives much in the past and can often, she says, feel John’s presence, accuses the cousin of betraying to “Big Sam” her relations with John Mayhew, Miriam exhibits the first of several fierce outbursts: “Why wouldn’t I tell him that his pure, darling little girl was having a dirty, little affair with a married man?”

As for who slashed Miriam’s dress, it was Velma, who didn’t like Miriam and wanted her to leave. Miriam says to her “You seem to know it was ripped – and I didn’t mention it to anyone.” Miriam’s next line, “And it isn’t just the dress” seems to imply that Velma also planted the hatchet (and fake hand) for her to find, not knowing that Charlotte would see it too. I’ve found that part to be a bit far-fetched. Watch it again.

What happens to Charlotte at the end… is she sent to an insane asylum or is she sent to gaol?

She’s carted off to the hoozgow.