Opera, which has an even less than five per cent following among the general population, appears occasionally in the movies as source music—sometimes with effective, even plot-altering results. It’s often men who prompt in others, usually women, a dramatic or romantic turnaround. Three movies come immediately to mind. In Pretty Woman, Richard Gere uses Verdi to convince Julia Roberts that her previous occupation doesn’t matter to him. In Moonstruck, Nicholas Cage has a partner in Puccini, the two convincing Cher that Cage is better husband material than his wishy-washy brother (Danny Aiello). In The Shawshank Redemption, where no women were present, a creative Tim Robbins plays, through the intercom system of a prison, an opera recording of a bewitching soprano aria from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, mesmerizing the hardened criminals. A fourth film is a little different, its “opera” connection turning sour. Yes, now the love is of an adulterous nature. Seems Michael Douglas is having an affair with seductive whacko Glenn Close, and Puccini (again) is part of her siren call.

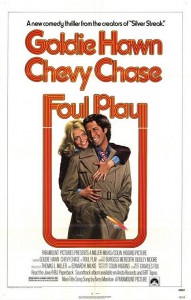

A rip-off of Hitchcock, Foul Play borrows the kidnapping of a bishop from Family Plot and the assassination at a concert hall from The Man Who Knew Too Much. In the climax, the film makes shambles of a performance of The Mikado. If not opera, the operetta is close to it. In Topsy-Turvy, there is a more serious look at The Mikado as its creators, William S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan (Jim Broadbent and Allan Corduner), prepare for its premiere. The film is among the better biographies, with many of the songs intact and marred only by some gratuitous nudity.

A rip-off of Hitchcock, Foul Play borrows the kidnapping of a bishop from Family Plot and the assassination at a concert hall from The Man Who Knew Too Much. In the climax, the film makes shambles of a performance of The Mikado. If not opera, the operetta is close to it. In Topsy-Turvy, there is a more serious look at The Mikado as its creators, William S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan (Jim Broadbent and Allan Corduner), prepare for its premiere. The film is among the better biographies, with many of the songs intact and marred only by some gratuitous nudity.

One of the earliest, still-remembered composer biographies is Song of Love—Paul Henreid and Katharine Hepburn as Robert and Clara Schumann, Robert Walker (!) as Johannes Brahms and Henry Daniell as Franz Liszt. And poor old Liszt in Song Without Love receives from Hollywood as preposterous a biography as can be imagined. Dick Bogarde is the composer and Capucine his paramour, the Princess Carolyne Wittgenstein. The only image I remember from the film is Bogarde walking outside a concert hall—the camera on his feet—as, from inside the building, is heard Wagner’s Rienzi Overture.

One of the earliest, still-remembered composer biographies is Song of Love—Paul Henreid and Katharine Hepburn as Robert and Clara Schumann, Robert Walker (!) as Johannes Brahms and Henry Daniell as Franz Liszt. And poor old Liszt in Song Without Love receives from Hollywood as preposterous a biography as can be imagined. Dick Bogarde is the composer and Capucine his paramour, the Princess Carolyne Wittgenstein. The only image I remember from the film is Bogarde walking outside a concert hall—the camera on his feet—as, from inside the building, is heard Wagner’s Rienzi Overture.

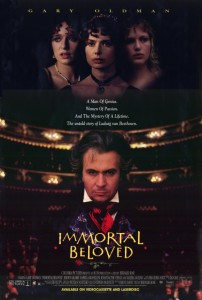

As some of these movies illustrate—I think Topsy-Turvy is pretty good—composer biographies are generally boring and usually grossly inaccurate. Such a film is the opulent looking but shoddily researched Immortal Beloved, based on an hypothesis of the identity of the unnamed women in three love letters found in Beethoven’s desk after his death. Gary Oldman is ideally cast, and he does his best, but the images and sounds that haunt me are violin bowing out of sync with the string sound and small, gut-stringed eighteenth-century orchestras imitated on the soundtrack by the modern, eighty-piece London Symphony.

As some of these movies illustrate—I think Topsy-Turvy is pretty good—composer biographies are generally boring and usually grossly inaccurate. Such a film is the opulent looking but shoddily researched Immortal Beloved, based on an hypothesis of the identity of the unnamed women in three love letters found in Beethoven’s desk after his death. Gary Oldman is ideally cast, and he does his best, but the images and sounds that haunt me are violin bowing out of sync with the string sound and small, gut-stringed eighteenth-century orchestras imitated on the soundtrack by the modern, eighty-piece London Symphony.

Death in Venice is about an egocentric, Mahler-like composer (Bogarde again) featuring Mahler’s music, including the Adagietto of the Fifth Symphony, a love song for his wife, Alma. The biggest blockbuster among composer biographies is, of course, Amadeus. It was lushly filmed in Prague, with an Oscar-winning performance by F. Murray Abraham as Salieri, Mozart’s supposed rival in late eighteenth-century Vienna. The film is worth seeing for his performance alone, as well as for Jeffrey Jones’ as Emperor Joseph II, though I for one have never been able to accepted Tom Hulce as Mozart.

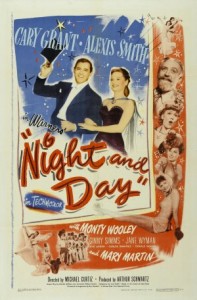

Broadway composers fare no better in Hollywood. Two of the worst—merely platforms for a lot of songs—are Night and Day (Cary Grant as Cole Porter) and Till the Clouds Roll By (Robert Walker as Jerome Kern). Robert Alda is a wooden George Gershwin in Rhapsody in Blue and there is the typical slight of hand with the facts, but the film is well mounted and interestingly paced. I remember Gershwin’s father (Morris Carnovsky) checking his watch: the longer the composition, he reasoned, the better it would be.

Broadway composers fare no better in Hollywood. Two of the worst—merely platforms for a lot of songs—are Night and Day (Cary Grant as Cole Porter) and Till the Clouds Roll By (Robert Walker as Jerome Kern). Robert Alda is a wooden George Gershwin in Rhapsody in Blue and there is the typical slight of hand with the facts, but the film is well mounted and interestingly paced. I remember Gershwin’s father (Morris Carnovsky) checking his watch: the longer the composition, he reasoned, the better it would be.

Among all those movies that involve classical music in one way or another, my favorites are those about musicians, their lives and work. In The Great Lie, Mary Astor is a pianist, playing Tchaikovsky’s ultra-famous B-Flat Minor Concert. Her concert appearances are few, and musical references are nil, as much of the film centers on the relationship between Astor and Bette Davis. Bette’s husband George Brent is lost in an airplane crash, and the two women subsequently share the confining space of an isolated motel while the lady musician has Brent’s baby from an earlier affair.

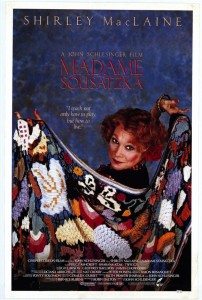

In one of Shirley MacLaine’s neglected treasures, Madame Sousatzka, the actress plays a piano teacher, and there is a plethora of piano music by Brahms, Schubert, Liszt, Beethoven, Schumann, Scriabin, Chopin and Mendelssohn. With an occult twist in The Mephisto Waltz, Alan Alda’s talent is transferred to a dying pianist (Curt Jurgens), and the title piece by Franz Liszt plays an important part, both as part of Goldsmith’s score and as the piano composition played on screen.

In one of Shirley MacLaine’s neglected treasures, Madame Sousatzka, the actress plays a piano teacher, and there is a plethora of piano music by Brahms, Schubert, Liszt, Beethoven, Schumann, Scriabin, Chopin and Mendelssohn. With an occult twist in The Mephisto Waltz, Alan Alda’s talent is transferred to a dying pianist (Curt Jurgens), and the title piece by Franz Liszt plays an important part, both as part of Goldsmith’s score and as the piano composition played on screen.

In Intermezzo, another piano teacher (Ingrid Bergman) becomes involved with her young pupil’s father (Leslie Howard), a concert violinist. Most important, the film marked Ingrid’s Hollywood début. It was also a showcase for Grieg’s Piano Concerto, Tchaikovsky’s “None But the Lonely Heart,” Sinding’s “Rustles of Spring” and Heinz Provost’s “Intermezzo,” played on screen in various forms and behind the main title.