“But Marx wasn’t a German, Marx was a Jew.”— Professor Charles Rankin

“But Marx wasn’t a German, Marx was a Jew.”— Professor Charles Rankin

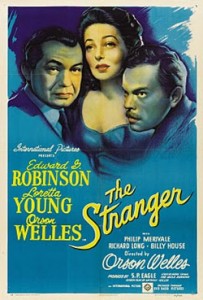

Having just watched The Stranger for the first time in a long while, I had forgotten that the film, besides being a suspense, a mystery and a Nazi-in-hiding caper, is, after all, an excellent example of film noir. In 1946, when The Stranger was made, that style, given its name by the French, was much in vogue. Herein are dark and light, shadows, black corners, askew angles, exaggerated perspectives and, equally necessary, a moody, depressing story line about disreputable individuals—at least two in this case, not counting a minor offender, a crafty, checker-playing drug store proprietor.

The noir elements are accentuated by the film’s director and the plot’s principal villain, Orson Welles, who, with every camera movement—the cinematographer is none other than Russell Metty—captures the very mood of the genre, as both men had done, perhaps most brilliantly, in Touch of Evil. The Stranger was made the same year as Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, both based on a similar premise—escaped Nazis loose in the Western Hemisphere. In Notorious it is Rio de Janeiro, in The Stranger a sleepy little town in New England.

Briefly—well, probably not too briefly—the plot is this: An agent of the War Crimes Commission, known only as “Mr. Wilson” (Edward G. Robinson), insists on deliberately letting escape a known Nazi, Konrad Meinike (Konstantin Shayne, who, small world, would later appear in Hitch’s Vertigo). Wilson hopes that Meinike will lead him to the notorious Holocaust criminal Franz Kindler, who has managed, or so it seems, to erase all evidence of his former existence.

Briefly—well, probably not too briefly—the plot is this: An agent of the War Crimes Commission, known only as “Mr. Wilson” (Edward G. Robinson), insists on deliberately letting escape a known Nazi, Konrad Meinike (Konstantin Shayne, who, small world, would later appear in Hitch’s Vertigo). Wilson hopes that Meinike will lead him to the notorious Holocaust criminal Franz Kindler, who has managed, or so it seems, to erase all evidence of his former existence.

Meinike leads Wilson to Harper, Connecticut. The agent carries with him books on clocks, since the solitary link to Kindler is his fascination with clocks. Aware he’s being followed, Meinike doubles back on his pursuer in the gym of a local school and, from a balcony, tosses an exercise ring “from on high” down on Wilson, who, rather foolishly, had walked onto an open basketball court. Wilson is presumed dead from a blow to the head.

In a visit that will prove crucial for Kindler, as he himself will later say, Meinike stops by the home of Mary Longstreet (Loretta Young). Mary is hanging curtains on the day of her marriage to Charles Rankin, a history professor at the school. Meinike, who had gotten the address from a Nazi-connected passport photographer, waits impatiently for Rankin to arrive, then leaves.

Moments later (in film time), Meinike meets Rankin on the school grounds during a paper chase by some of the boys. From an elevated camera—much of the following will be so shot—Meinike approaches and is embraced by Rankin, who displays an arrogant complacency. “Who would think to look for the notorious Franz Kindler,” he says, “in the scared precincts of the Harper School, surrounded by the sons of America’s first families?” And adds that, that day, he will marry the daughter of a justice of the Supreme Court, “a famous liberal.”

Moments later (in film time), Meinike meets Rankin on the school grounds during a paper chase by some of the boys. From an elevated camera—much of the following will be so shot—Meinike approaches and is embraced by Rankin, who displays an arrogant complacency. “Who would think to look for the notorious Franz Kindler,” he says, “in the scared precincts of the Harper School, surrounded by the sons of America’s first families?” And adds that, that day, he will marry the daughter of a justice of the Supreme Court, “a famous liberal.”

This is my favorite scene in the entire film, and it was actually much longer until edited by the studio; with a long history of studio meddling—witness The Magnificent Ambersons mutilation— Orson Welles was probably not surprised.

When Meinike says he’s received word “from the all highest,” Rankin stammers, “You don’t mean——,” assuming the reference is to Hitler. But as the old man rambles on, he realizes he’s talking about God and responds with a chuckle, “You, Konrad—a religious . . . ,” almost finishing with “fanatic.” For the first time in the scene, Bronislau Kaper’s music enters. Rankin mutters, “U-huh.” Meinike says he was followed but that he killed the man, the man with the pipe, “striking from on high—down.”

As they continue walking and Meinike babbles on, Rankin, head down, mutters again to himself, “U-huh,” and, once more, “U-huh,” done as only Orson Welles can do, vague yet unsettling, his eyes looking around—not nervously or desperately, but patiently, the calculating thoughts etched on his face. Meinike suggests they pray together and kneels, Rankin standing beside him, his eyes still darting about, seeming to consider the woods. He’s obviously thinking, even as he repeats some of the words Meinike has him say. Rankin has a hand on the man’s shoulder, then, as the prayer continues, both his hands move slowly to Meinike’s throat.

Bronislasu Kaper’s orchestra comes to the fore with a great clamor as Meinike is dragged to the ground, conveniently behind a bush, with his right hand clutching Rankin’s coat, then dropping lifelessly. Throughout the film, Bronislau Kaper gives admirable support, somehow, when the temptation could have been otherwise, finding the right compromise between over-the-top melodrama and obtuse understatement. During his career, Bronislau Kaper was almost as neglected as Alex North, and, like Alex North, easily adapted to different film genres; take for example the range of Bronislau Kaper’s scores: Gaslight (1944), Them!, Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), Lili, A Day at the Races and The Naked Spur.

Bronislasu Kaper’s orchestra comes to the fore with a great clamor as Meinike is dragged to the ground, conveniently behind a bush, with his right hand clutching Rankin’s coat, then dropping lifelessly. Throughout the film, Bronislau Kaper gives admirable support, somehow, when the temptation could have been otherwise, finding the right compromise between over-the-top melodrama and obtuse understatement. During his career, Bronislau Kaper was almost as neglected as Alex North, and, like Alex North, easily adapted to different film genres; take for example the range of Bronislau Kaper’s scores: Gaslight (1944), Them!, Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), Lili, A Day at the Races and The Naked Spur.

In 1946, at an Alphabet City High School in Manhattan, I sat among the flotsam and jetsam of WWII. At some desks were seated unrepentant Poles and at others cringing Poles! Film awakens echos of that past time.