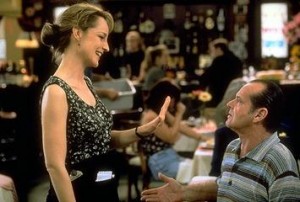

As Good As It Gets came sixteen years after Arthur. Here Jack Nicholson is an obsessive-compulsive who must have the same restaurant table every morning for breakfast, otherwise he can’t eat. He brings his own plastic ware and insists that only waitress Helen Hunt can satisfy his gastronomic needs. She has two immediate impressions of him: “When you first entered the restaurant, I thought you were handsome, and then, of course, you spoke.” Toward the end of the film, in a high class restaurant, Jack seems about to bring Helen around when he makes another grand faux pas and sends her storming from the place.

As Good As It Gets came sixteen years after Arthur. Here Jack Nicholson is an obsessive-compulsive who must have the same restaurant table every morning for breakfast, otherwise he can’t eat. He brings his own plastic ware and insists that only waitress Helen Hunt can satisfy his gastronomic needs. She has two immediate impressions of him: “When you first entered the restaurant, I thought you were handsome, and then, of course, you spoke.” Toward the end of the film, in a high class restaurant, Jack seems about to bring Helen around when he makes another grand faux pas and sends her storming from the place.

In Five Fingers, James Mason is enjoying a repast on a hotel balcony in Rio de Janeiro when he learns that all the money he had acquired from the Germans through careful espionage is counterfeit. He laughs hysterically, letting the wind take the fake bills from his hands as the camera pulls back for the last shot. Filmed and acted with graphic, earthy sexual innuendo, the meal shared by Albert Finney and Diane Cilento in Tom Jones is an erotic prelude to an upstairs consummation. A meal is a prelude to something quite different in Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H: John Schuck is given a farewell suicide banquet by hosts that include Elliott Gould, Donald Sutherland and Tom Skerritt.

Sailors must eat, too. In Master and Commander, when Russell Crowe as Captain Jack Aubrey asks of his officers during supper in the great cabin which of two weevils crawling on a plate is the fittest, he corrects Paul Bettany’s thoughtful and scientific reply: “Do you know that in the service”—a long pause—“one must always choose the lesser of two weevils?”

Sailors must eat, too. In Master and Commander, when Russell Crowe as Captain Jack Aubrey asks of his officers during supper in the great cabin which of two weevils crawling on a plate is the fittest, he corrects Paul Bettany’s thoughtful and scientific reply: “Do you know that in the service”—a long pause—“one must always choose the lesser of two weevils?”

In a well-made scene in The Sea Hawk, with superb underpinning by Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s score, Captain Errol Flynn’s Spanish passengers (Claude Rains and Gilbert Roland) admire his Spanish-engraved dinnerware and discuss cheese stolen from the governor’s cellar at Cartagena. When Flynn proposes a toast, Brenda Marshall gets up to leave, assuming it’s for her and wishing to register her disproval of the captain; she’s embarrassed to learn the toast is for the Queen of England.

Cheese also plays a part in another sea saga, Mutiny on the Bounty. In the 1962 remake, not a captain but First Lieutenant Marlon Brando comments on that delicacy in another great cabin, on Captain Trevor Howard’s little vessel of the title. Marlon Brando as Fletcher Christian suggests that, after a sailor’s recent flogging over the theft of a pound of cheese, the cheese on their table might be “tainted.” After this pronouncement, he methodically folds on his chest his napkin, in halves then quarters, a tick of Marlon Brando’s sometimes eccentric performance that later includes a nightcap, nightgown and long-stemmed pipe, probably all his ideas.

It was, indeed, a bizarre nautical meal that Captain James Mason served his newly dried-out guests in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. “Nothing here is of the earth,” he boasts, offering guests Kirk Douglas, Peter Lorre and Paul Lukas such delights as fillet of sea snake, brisket of blowfish basted in barnacles, milk from the giant sperm whale, preserves from sea cucumbers and the always gastronomical pleaser, sauté of unborn octopus. “Nothing here is fit to eat!” Douglas exclaims.

It was, indeed, a bizarre nautical meal that Captain James Mason served his newly dried-out guests in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. “Nothing here is of the earth,” he boasts, offering guests Kirk Douglas, Peter Lorre and Paul Lukas such delights as fillet of sea snake, brisket of blowfish basted in barnacles, milk from the giant sperm whale, preserves from sea cucumbers and the always gastronomical pleaser, sauté of unborn octopus. “Nothing here is fit to eat!” Douglas exclaims.

1946’s Deception has one of the longest dining scenes in movie history—and one of the best. Before the dress rehearsal for his new concerto, composer Claude Rains treats the untried cellist Paul Henreid and both men’s former lover Bette Davis to dinner at a swank restaurant. To deliberately unnerve Henreid, the composer orders and reorders the meal. “Darling,” Davis remarks to Henreid, “believe it or not, there are places, here in New York, where you can put a nickel in a slot and something comes out immediately.”

With mock frustration, Rains moans, “I do hope the great haste with which we’re assembling this slapdash repast is not going to affect me internally and render me incapable of appreciating good music.” After presumably having settled earlier on a woodcock and ordered all its fine accouterments, Rains muses to his guests as they leave the restaurant, “Maybe we should’ve had the woodcock.”

Over the dinner table in Enchanted April, wife Miranda Richardson informs husband Jim Broadbent that she and three other women are going to vacation in Italy—to find themselves; at a supper table with a prairie family in The Searchers, new arrival John Wayne reveals his racism toward Jeffrey Hunter, who is part Cherokee; in the dinner party climax of The Thin Man, William Powell examines the case and identifies the murderer; in an outdoor feeding in Witness, farmers come to erect a barn for newly weds; at the dismal Christmas supper in Gone With the Wind, Laura Hope Crews informs her family that they mustn’t drink all the wine, as this is the last bottle.

Alfred Hitchcock films alone could form the basis for a lengthy treatise on the subject of food: in The 39 Steps, the supper meal in the farmer’s cottage with Peggy Ashcroft and the escaped “criminal” Robert Donat; in Spellbound, the meal attended by Gregory Peck and Ingrid Bergman and the fork prong pattern in the tablecloth that sets off Peck; in the blind man’s shack in Saboteur, between Robert Cummings and Alan Baxter, with its echoes of the blind man scene in Frankenstein; in the dining car in Strangers on a Train, Robert Walker’s proposal to Farley Granger that they swap murders; in the back room of the motel in Psycho, Janet Leigh’s sandwich and Tony Perkins’ discussion of his taxidermy hobby and his “we’re all in our private traps” speech; in To Catch a Thief, in the convertible, the picnic between Cary Grant and Grace Kelly, when, once again over chicken, an actress asks an actor whether he prefers “a leg or a breast”!