Hitch’s Shadow of a Doubt has numerous dining scenes, principally at the home where Joseph Cotton has come for a visit and to elude police. In the first he tries to distract the family from identifying the Merry Widow waltz Teresa Wright is humming, because he is the Merry Widow Murderer and passes out gifts taken from his victims. Later Hume Cronyn interrupts another dinner to talk hypothetical murder with Henry Travers, the house’s head and fellow crime hobbyist. Even later, over drinks at a bar, Cotton reveals his darkest side to Wright in his “foul sty” tirade.

Hitch’s Shadow of a Doubt has numerous dining scenes, principally at the home where Joseph Cotton has come for a visit and to elude police. In the first he tries to distract the family from identifying the Merry Widow waltz Teresa Wright is humming, because he is the Merry Widow Murderer and passes out gifts taken from his victims. Later Hume Cronyn interrupts another dinner to talk hypothetical murder with Henry Travers, the house’s head and fellow crime hobbyist. Even later, over drinks at a bar, Cotton reveals his darkest side to Wright in his “foul sty” tirade.

While in Frenzy the director made more use of the metaphor of food than in any other film, often, though, in bad taste, Notorious is less offensive in its comments on both food and drink. Ingrid Bergman is intoxicated in the opening scene and often thereafter—and on a park bench Cary Grant misreads her being poisoned with another hangover. There’s the dinner at Claude Rains’ house where the Nazis become unduly excited over a bottle of wine. The romantic balcony dinner Bergman prepares for her “dreamboat” becomes cold when Grant has to leave, and, too, he forgets a bottle of wine when he returns. Hitch’s metaphor of drink extends to coffee that contains poison and wine bottles that contain uranium ore.

While in Frenzy the director made more use of the metaphor of food than in any other film, often, though, in bad taste, Notorious is less offensive in its comments on both food and drink. Ingrid Bergman is intoxicated in the opening scene and often thereafter—and on a park bench Cary Grant misreads her being poisoned with another hangover. There’s the dinner at Claude Rains’ house where the Nazis become unduly excited over a bottle of wine. The romantic balcony dinner Bergman prepares for her “dreamboat” becomes cold when Grant has to leave, and, too, he forgets a bottle of wine when he returns. Hitch’s metaphor of drink extends to coffee that contains poison and wine bottles that contain uranium ore.

Giving new meaning to “dining alone,” in Separate Tables the guests of the hotel have individual tables—and always the same tables. The theme of the film is loneliness, and what better symbolizes the isolation of souls than the island-like quarantine of dining tables? The separation is broken in the film’s climax when the residents approach David Niven’s table and personally support him against the domineering Gladys Cooper, who had campaigned for the man’s eviction because of a personal indiscretion.

On occasions, something other than food may be brought to the dining table, as in House of Fear, one of the Basil Rathbone/Sherlock Holmes films for Universal. An envelope containing a dwindling number or dried orange pips is delivered at dinnertime, a portent of death for the recipient. Under any other circumstances, the growing number of unsolved murders would not have looked good for dear old Sherlock, but the deaths are not what they seem, and the detective emerges with his career intact.

On occasions, something other than food may be brought to the dining table, as in House of Fear, one of the Basil Rathbone/Sherlock Holmes films for Universal. An envelope containing a dwindling number or dried orange pips is delivered at dinnertime, a portent of death for the recipient. Under any other circumstances, the growing number of unsolved murders would not have looked good for dear old Sherlock, but the deaths are not what they seem, and the detective emerges with his career intact.

And then, too, there are the planned dinners, picnics and banquets that never take place. In Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Gary Cooper prepares for a romantic dinner date with his “lady in distress” Jean Arthur, even using butler Barnett Parker as her stand-in at the probable table, making him slouch down to approximate her height and ordering a smaller bouquet of flowers that won’t obstruct his view of her. He learns, however, Arthur is the reporter who has been demeaning him in the headlines and he goes into deep depression.

In the climax of The Night of the Generals, Peter O’Toole is attending a reunion of his old German outfit from World War II. He was a psychotic sex murderer during that conflict, and, now, in all the excitement of comrades reunited, he is confronted by a witness, Tom Courtenay, he had allowed to escape. With no way out and asking to borrow a gun, O’Toole steps into the empty banquet hall. After a single shot, the door is opened and he is found sprawled dead on a section of the tables.

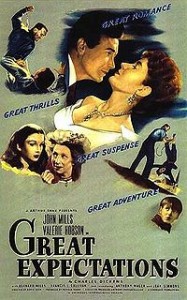

In Great Expectations (1947), Martita Hunt as the mad Miss Havisham shows young Anthony Wager the remains of a grand reception table, with its great cake, all decaying and covered in cobwebs and infested with rats. No guests ever ate here. Clocks throughout the house had been stopped at the moment of her jilting at the altar, and she forever sits at the head of the table, wearing the white dress from her wedding day. “The mice have gnawed at the cake,” she says, “and sharper teeth than teeth of mice have gnawed at me.”

In Great Expectations (1947), Martita Hunt as the mad Miss Havisham shows young Anthony Wager the remains of a grand reception table, with its great cake, all decaying and covered in cobwebs and infested with rats. No guests ever ate here. Clocks throughout the house had been stopped at the moment of her jilting at the altar, and she forever sits at the head of the table, wearing the white dress from her wedding day. “The mice have gnawed at the cake,” she says, “and sharper teeth than teeth of mice have gnawed at me.”

There are, of course, some disgusting dinner table “delights.” Veronica Cartwright suffers the foulest possible acid reflux in The Witches of Eastwick—remember? And poor Robert Morley in Theater of Blood catches the worst of the other way, having a meat (poodle!) pie force-fed by master chef Vincent Price, a ham Shakespearian actor wreaking revenge on his unsympathetic critics. The play Price is parodying is Titus Andronicus, and director-screenwriter Julie Taymor renders a modern adaptation in Titus. Like the Price wade-through, there are numerous and tasteless killings. In only one incident of bloody overkill, Anthony Hopkins bakes two of Queen Jessica Lange’s sons in a pie, which she is served and eats unknowingly.

To close this anthology of eating in the movies, a more recent dining scene is worthy of standing alongside the best of the best, although Meet the Parents doesn’t maintain this comic level. Teri Polo has brought boyfriend Ben Stiller home to meet her parents, Robert De Niro and Blythe Danner. At the dining table, De Niro recites his poem about his late mother, with such “moving” lines as “While the cancer ate away your organs,/Like an unstoppable rebel force.” Proposing a toast from some cheap Seven-Eleven wine, Stiller pops the cork. The cork strikes the ornate urn containing the mother’s ashes and crashes to the floor. Jinx the cat, ever alert for, say, fertile potted plants, darts over and begins pawing in the gray pile of ash.

To close this anthology of eating in the movies, a more recent dining scene is worthy of standing alongside the best of the best, although Meet the Parents doesn’t maintain this comic level. Teri Polo has brought boyfriend Ben Stiller home to meet her parents, Robert De Niro and Blythe Danner. At the dining table, De Niro recites his poem about his late mother, with such “moving” lines as “While the cancer ate away your organs,/Like an unstoppable rebel force.” Proposing a toast from some cheap Seven-Eleven wine, Stiller pops the cork. The cork strikes the ornate urn containing the mother’s ashes and crashes to the floor. Jinx the cat, ever alert for, say, fertile potted plants, darts over and begins pawing in the gray pile of ash.

Bon appétit.