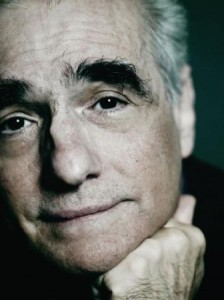

“I think the immediate connection, when I read [Taxi Driver], was with the anger and the rage, and the loneliness—not being part of a group. I was always on the outside. You grow up in a neighborhood where what a ‘man’ is, quote unquote, is a guy who can go into a room and slam some people around and win . . . But on the other hand, I heard my father say different things about what a man is; that had to do with being morally strong.” —Martin Scorsese

“I think the immediate connection, when I read [Taxi Driver], was with the anger and the rage, and the loneliness—not being part of a group. I was always on the outside. You grow up in a neighborhood where what a ‘man’ is, quote unquote, is a guy who can go into a room and slam some people around and win . . . But on the other hand, I heard my father say different things about what a man is; that had to do with being morally strong.” —Martin Scorsese

Martin Scorsese has a reputation, and properly so, as a director of dark, realistic, hard-driving dramas about New York gangs and gangsters, dysfunctional families, the dispossessed and the loneliness, sometimes brutality, of living on the fringes of society—dark pictures, indeed. In a series of extended conversations between the director and film critic Richard Schickel, Martin Scorsese is revealed—at times “exposed” is a more apt word—as a vulnerable, sometimes insecure man who has had a drug problem and has persistent doubts about his Catholic faith, even the right direction of his career as possibly the number one director active today.

“I figured pretty much,” he says, “that [The Departed, 2006] would be it for me, that I wouldn’t do any more studio pictures. More independent films. I didn’t see where I could fit into the system any more . . . Because, ultimately, the marketplace for big-budget films means there will be less experimentation in them. . . . At my age, having gone through what I have, I don’t know whether it’s worth it any more.”

“I figured pretty much,” he says, “that [The Departed, 2006] would be it for me, that I wouldn’t do any more studio pictures. More independent films. I didn’t see where I could fit into the system any more . . . Because, ultimately, the marketplace for big-budget films means there will be less experimentation in them. . . . At my age, having gone through what I have, I don’t know whether it’s worth it any more.”

Richard Schickel mentions in the first line of his introduction that he and the director are “an odd couple.” “I grew up,” Richard Schickel points out, “in a placid suburb of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, cosseted by my middle-class family—loving, indulgent, always avoiding openly expressed emotions.” By contrast, Richard Schickel continues, “Marty’s young years were, of course, the opposite, spent mainly in Little Italy on New York’s Lower East Side—working class, but also criminal class, with . . . an element of anxiety in his home, which was rife with discussions of complex family issues tensely, if lovingly, argued out.”

Richard Schickel writes that he “gravitated to the movies because I was looking for melodramatic excitement, a relief from the ‘niceness’ that was the highest value of that time and place.” Martin Scorsese, by contrast, “was escaping a vastly different sort of reality when he went to the movies—melodrama and fantasy, to be sure, but of a kind that was actually less threatening than the harsh realities this asthmatic little boy encountered in his daily life.” And, between the two men, there is that additional contrast of religion—the director a confirmed, yet doubting Catholic, the interviewer a “born atheist,” an admission which Martin Scorsese nonchalantly discounts with a, “Yeah, okay,” perhaps disbelieving, or not wanting to go there.

Different views between the two men occasionally surface, as in the chapter on Shutter Island. Richard Schickel apparently opens the proverbial flood gates when he remarks, “I found myself very lost in this movie. And not in a good way.”

Different views between the two men occasionally surface, as in the chapter on Shutter Island. Richard Schickel apparently opens the proverbial flood gates when he remarks, “I found myself very lost in this movie. And not in a good way.”

MS: “I don’t even want to talk about it because it’s like I can’t handle any more criticism of it. Sorry.”

RS: “I don’t mean it as criticism.”

MS: “You either go with it or you don’t.”

RS: “There was some reality I couldn’t embrace in that movie. I don’t know how to explain it in any other way.”

MS: “Maybe that’s it. Maybe it’s no good. I don’t know.”

RS: “I’m not saying it’s no good, Marty.”

MS: “No, maybe it isn’t. I really don’t know. . . . Some people were really stunned by it. Others can’t get into it at all—can’t feel, as you say, the reality.”

Much like François Truffaut’s book-form interview with Alfred Hitchcock back in 1966, the Scorsese films are taken in chronological order. Hitch seems to concentrate more on the technical aspects of film making and the comparative worth of his achievements, while generally remaining secretive about his personal life; Martin Scorsese often discusses technical problems and the tamperings by the studios, and unpretentiously bares his anger, doubts and insecurities.

Following Martin Scorsese’s growing up experiences in Little Italy, Richard Schickel draws from him his early and divergent movie influences, especially John Ford, The Searchers being perhaps the most often-mentioned non-Scorsese film in the interviews. That and Elia Kazan’s East of Eden; the quarrels between two brothers and the contest for their father’s love remind Scorsese of his own familial relationships.

The director relates the nearly nightly confrontations, in the 1950s, with his own brother. The fights, he says, were “Over how to live. How to behave. Or how to be a man. I’m not saying one’s right or wrong. And the quiet one, the sickly one, me, had to take it all in and couldn’t say anything. And I was getting pretty angry about it.” The anger “was probably against my father. But I also wanted to love my father. And I know he loved me. But he had to be very stern. He had to be very tough.”

As a native New Yorker and a Martin Scorsese fan (or is that redundant? :-)), I very much enjoyed reading Schickel’s interview with Scorsese. I got a kick out of his anecdote about showing his friend being “so literal” about storyboards!