There was, too, Martin Scorsese’s early desire to go into the priesthood. “ . . . then I began to think this vocation I had was for the wrong reason—it shouldn’t be about you, it should be about others . . . I think I made the decision not to go when I went to my first class at Washington Square College, which had to do with movies.”

The brilliant Technicolor in Duel in the Sun impressed Scorsese when the film was released in 1946, as did, later, a shootout in Bonnie and Clyde, an influence on his second movie, Boxcar Bertha, both pictures set in the 1930s. He admits to being enticed as a kid by those ridiculous “sword and sandal” films—The Silver Chalice and Land of the Pharaohs. “But they’re bad,” the director adds.

The brilliant Technicolor in Duel in the Sun impressed Scorsese when the film was released in 1946, as did, later, a shootout in Bonnie and Clyde, an influence on his second movie, Boxcar Bertha, both pictures set in the 1930s. He admits to being enticed as a kid by those ridiculous “sword and sandal” films—The Silver Chalice and Land of the Pharaohs. “But they’re bad,” the director adds.

Scorsese’s first feature film was Who’s That Knocking at My Door, and, to his disgust, a distributor could not initially be found until an irrelevant nude scene, filmed in Amsterdam, was added. “Roger Ebert,” Scorsese says, “was the critic who came out for the picture when it was shown under a different title at the Chicago Film Festival. That was the year before we put the nude scene in. And he gave us a very nice review.”

After a discussion of the director’s latest theatrical film, Shutter Island, the remainder of the interviews are devoted to his use of storyboards; the variety of colors and tints he achieves in individual films, sometimes varying the color frame to frame; his camera technique; his approach to, and appreciation of, different actors, his favorites being Robert De Niro, Harvey Keitel, Daniel Day-Lewis and, most recently, Leonardo DiCaprio; the importance of music in his films, both as source music and as background scores; his crusade for film restoration; and his fascinating hobby of collecting old movie posters.

As for the storyboarding, which he has used for all his film, Scorsese relates, when he was eight or nine, “I would watch shows on TV and try to do my version on film, in drawings. I would show them to this one friend of mine because he was a very sweet kid. . . . ‘Marty, these don’t move.’ I said, ‘They all move. See, from one frame to the other.’ ‘Oh, yeah, but the drawings are not moving.’ I said, ‘Why do you have to be literal about it?’ ”

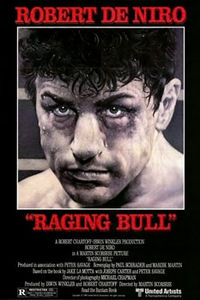

There are, of course, those films—the bulk of his output—which bear most forcefully the Scorsese stamp, often dark and brooding, often bloodily graphic, including Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, After Hours, Mean Streets, The Color of Money, the Cape Fear remake, Gangs of New York, The Departed and, of course, Goodfellas, which many consider the best of all his movies.

There are, of course, those films—the bulk of his output—which bear most forcefully the Scorsese stamp, often dark and brooding, often bloodily graphic, including Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, After Hours, Mean Streets, The Color of Money, the Cape Fear remake, Gangs of New York, The Departed and, of course, Goodfellas, which many consider the best of all his movies.

The director has delved into other genres, with mixed results, usually positive, though—straight dramas (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), black comedies (The King of Comedy), period pictures (The Age of Innocence, one of his few missteps), documentaries (The Last Waltz), even an aberrant variation of the “sword and sandal” epic (The Temptation of Christ), which brought unexpected negative, even hateful attacks.

If you are a Scorsese fan, you’ll clearly enjoy this book. The imprint you have of his screen images, however, may not now match your assumptions about the man, once you know him through these interviews. If not a fan, you might be easily, irresistibly fascinated by him. He is, after all, a thinking director—cultured, with wide-ranging interests, a craftsman with an artist’s understanding of lighting, color, camera and dialogue, as conscientious a creator of film as Hitchcock, Ford or William Wyler. His conversations are direct and unpretentious, and if Schickel as an interviewer lacks the instincts and insights of a Truffaut, it’s a small weakness of the book. One annoying practice, however, is the omission of quotation marks when the men are quoting individuals—not, as I recall, when citing lines from films.

Whether it was intentional or not, religion—Catholicism, the tortures of doubt, what it means to be a Christian, all those trappings—is one of the persuasive, or, if you like, pervasive, elements in the book. And rightly so, as religion is perhaps the strongest force in Scorsese’s life. His being a “religious” man, doubts and all, it seems fitting that he should have the final word here:

“If you have faith, that’s a good thing. Whether I have my faith or not, personally, is a constant struggle. But there’s a difference between faith and evolving in a spiritual way, a big difference. . . . But I shocked myself. I couldn’t even take the first minor step toward the spiritual life that I had in mind. I was very disappointed in myself about not being able to take that step.”

As a native New Yorker and a Martin Scorsese fan (or is that redundant? :-)), I very much enjoyed reading Schickel’s interview with Scorsese. I got a kick out of his anecdote about showing his friend being “so literal” about storyboards!