“You’re right, Mr. Thatcher. I did lose a million dollars last year. I expect to lose a million dollars this year. I expect to lose a million dollars next year. You know, Mr. Thatcher, at the rate of a million dollars a year, I’ll have to close this place—in sixty years.”— Charles Foster Kane

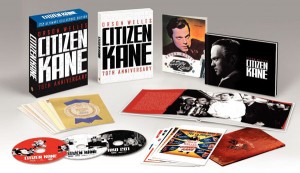

Good news for admirers of Citizen Kane. Warner Bros. has released, as of September 15, the 70th Anniversary Ultimate Collector’s Edition of the movie, a three-disc set on Blu-ray, DVD, On Demand and Digital Download. Accompanying the film is the award-winning commentary by Roger Ebert, touted earlier on this website, and also a separate commentary by Peter Bogdanovich. This first disc also includes interviews with Robert Wise and Ruth Warwick, deleted scenes, a press book, theatrical trailer, still photography comments by Ebert and other features.

The 1996 PBS documentary The Battle Over Citizen Kane—a masterpiece on its own—comprises the second disc. Introduced by David McCullough, it brilliantly traces the tragically similar lives of both media magnet William Randolph Hearst and New York radio/theater impresario Orson Welles, how each, in his own way, tried to destroy the other, how each experienced creative decline, misfortune and depreciation from moral and physical excesses.

The 1996 PBS documentary The Battle Over Citizen Kane—a masterpiece on its own—comprises the second disc. Introduced by David McCullough, it brilliantly traces the tragically similar lives of both media magnet William Randolph Hearst and New York radio/theater impresario Orson Welles, how each, in his own way, tried to destroy the other, how each experienced creative decline, misfortune and depreciation from moral and physical excesses.

The third disc contains RKO 281, the 1999 HBO movie starting Liev Schreiber as Orson Welles, James Cromwell as Hearst, Melanie Griffith as live-in mistress Marion Davies and Liam Cunningham as cinematographer Gregg Toland, plus roles for Louis B. Mayer, Louella Parsons, Carole Lombard, Hedda Hopper and other Hollywood luminaries in Welles’ orbit. By the way, 281 was the production number RKO Studios assigned Citizen Kane during filming.

For those able to take their eyes off the amazingly restored print—and it is amazing—there are two special items of old-fashioned reading material: a forty-eight-page collector’s book filled with photos and behind-the-scenes detail and a twenty-page reproduction of the original 1941 souvenir program, lobby cards and rare production memos.

For those able to take their eyes off the amazingly restored print—and it is amazing—there are two special items of old-fashioned reading material: a forty-eight-page collector’s book filled with photos and behind-the-scenes detail and a twenty-page reproduction of the original 1941 souvenir program, lobby cards and rare production memos.

So much has been written about Citizen Kane that saying something new, unless some fool should declare the 1941 film highly overrated, would seem impossible. Humbly, I’m not that fool, and agree that it is one of the greatest films ever made.

What could be said, which is unknown to some and forgotten by others who once knew, is that Citizen Kane was shamefully boycotted at the Oscar awards ceremony that honored the outstanding efforts of that year. The film received only one statuette from its nine nominations, for Original Screenplay by co-writers Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles.

Mankiewicz and Welles’ portrayal of Kane closely resembles Hearst—the excessive life style as lord of an estate, San Simeon, half the size of Rhode Island; the tyrannical abuse of friends and mistress; the feverish art collecting; the warmonger of the Spanish American War; the unprincipled newspaper publisher; and the lonely isolation later in life. Even Orson Welles, much later, admitted that his excessively vicious portrayal of Marion Davies, including Hearst’s attempt to make her a great movie star, was unfair and, in retrospect, regrettable; in the film, the mistress, now named Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore), is an untalented singer whom Kane tries to turn into a grand diva.

After a preview screening of the film, the enraged gossip columnist Hedda Hopper ran directly to Hearst with news of his negative portrayal. This publisher of yellow journalism did everything in his power to prevent the film’s release, suppressing any reference to Citizen Kane in his twenty-eight national newspapers, intimidating movie theater owners not to show the film and using blackmail and threats of an FBI investigation. Louis B. Mayer and other Hollywood moguls attempted to buy Citizen Kane in order to burn the negative. So, understandably, Academy voters were skittish, and, besides, soon after Welles’ arrival Hollywood had, collectively, come to resent this Boy Wonder upstart from the East.

After a preview screening of the film, the enraged gossip columnist Hedda Hopper ran directly to Hearst with news of his negative portrayal. This publisher of yellow journalism did everything in his power to prevent the film’s release, suppressing any reference to Citizen Kane in his twenty-eight national newspapers, intimidating movie theater owners not to show the film and using blackmail and threats of an FBI investigation. Louis B. Mayer and other Hollywood moguls attempted to buy Citizen Kane in order to burn the negative. So, understandably, Academy voters were skittish, and, besides, soon after Welles’ arrival Hollywood had, collectively, come to resent this Boy Wonder upstart from the East.

Beginning with the Best Picture category of 1941, How Green Was My Valley seems a good enough choice from among the ten nominations, that large number being the rule for most of the Academy’s history at that point. Two of Valley’s three most serious competitors were Sergeant York and The Maltese Falcon. And that third competitor, falling second alphabetically in the list, was Citizen Kane, which should have won Best Picture. Granted, there are some who challenge that majority which rates Kane as the greatest film ever made, but in 1941 it was, hands down, the best picture.

Welles as Kane, who on screen ages fifty years and experiences a drastic character deterioration, was among the nominees for Best Actor—and would have won in a normal environment. The trophy went, instead, to the safe choice of Gary Cooper, more or less playing his amiable self in Sergeant York. Too, it being only two months after Pearl Harbor, singling out an actor in the only war film of the five nominees was logical enough, perhaps patriotically necessary.

No one was nominated Best Actress from Kane, neither Warwick nor Comingore, and correctly so, as theirs were competent, if not particularly distinguished performances. The winner, Joan Fontaine, received Best Actress for Suspicion, a belated Oscar for a much superior performance in Rebecca the year before.

For director, newcomer Oscar Welles’ nomination was up against the greatness and well established laurels of William Wyler, John Ford and Howard Hawks. The Oscar was awarded to the always—well, nearly always—reliable Ford, clearly reliable in this case, for Valley. But for all the creative imagination Welles put into Citizen Kane, he should have won.

Not many years can match 1941 for stellar cinematographers. Among the nominees were Charles B. Lang, Arthur Miller, Joseph Walker, Rudolph Mate, Karl Freund, Joseph Ruttenberg, Sol Polito, Edward Cronjager—and that’s just in the black-and-white category! In Kane there were the long takes and deep focus of Gregg Toland who worked alongside an equally inspired Welles. Toland lost to Miller.

B&W Interior Decoration was, shall we say, “burdened” with eleven nominations. Citizen Kane, which had over a hundred sets, lost to the Valley movie. Color, which had yet to become the norm as a shooting medium, had only three nominations. In Sound Recording, Kane lost to That Hamilton Woman, thanks, and perhaps understandably so, to the naval battles. Film Editing in the Welles picture was the work of Robert Wise, soon to be a director in his own right; the Oscar went to William Holmes for, again, Sergeant York.

0 thoughts to “Citizen Kane (1941) with Orson Welles”