“I know it is coming, and I do not fear it, because I believe there is nothing on the other side of death to fear. I hope to be spared as much pain as possible on the approach path. I was perfectly content before I was born, and I think of death as the same state. I am grateful for the gifts of intelligence, love, wonder, and laughter.”—Roger Ebert

A moment ago, a movie reminiscence from me was in progress. It was a film from the 1950s. That movie has been around a while, so it’ll be here tomorrow. A book connected with movies has wonderfully distracted me. The film later, the book now.

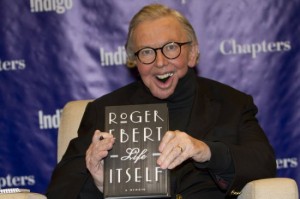

Roger Ebert’s latest is Life Itself: A Memoir. It’s worth reading. More than worth reading.

I had just finished more or less slogging through another kind of book, also from 2011. I won’t identify the author/title now, for I may tie the book to a later movie review. Point is, after reading, let’s say, this most disturbing book about World War II, not disturbing in subject matter, though that, too, but in its long-winded syntax, in its unrelenting, big sentence juggernaut style, reminiscent of lawyer density, with a cloud of esoteric words—after all that, it’s refreshing to enjoy the simple directness of Roger Ebert.

The autobiography opens with a typical Ebertian sentence—clean, straightforward, yet poetic, and in this case enigmatic: “I was born inside the movie of my life.” The mirror image, perhaps, of the opening lines in the introduction to his The Great Movies, Vol. I: “We live in a box of space and time. Movies are windows in its walls. They allow us to enter other minds—not simply in the sense of identifying with the characters, although that is an important part of it, but by seeing the world as another person sees it.”

The autobiography opens with a typical Ebertian sentence—clean, straightforward, yet poetic, and in this case enigmatic: “I was born inside the movie of my life.” The mirror image, perhaps, of the opening lines in the introduction to his The Great Movies, Vol. I: “We live in a box of space and time. Movies are windows in its walls. They allow us to enter other minds—not simply in the sense of identifying with the characters, although that is an important part of it, but by seeing the world as another person sees it.”

The Great Movies was then, the memoir is now. A lot has happened since 2002, almost ten years—a lot for Roger Ebert. Most people, interested in the movies and readers of this site, will know of his medical problems, his battle with cancer, the loss of his voice and other things besides. What many may not know is his close call with death. During most of his narration Roger alludes to his health only infrequently, sometimes almost offhandedly, only confronting the subject in chapters toward the end, and even then dwelling on it less analytically than, say, Christopher Hitchens and Steve Jobs have done.

Those last chapters, to my mind, are the best in the book. Perhaps unexpectedly, the subject is not the movies; perhaps not so unexpectedly, for Roger Ebert is a highly intelligent individual with wide ranging interests, he speaks of a broader view of life and spirituality, more the spirituality of oneself than an association with some divine being.

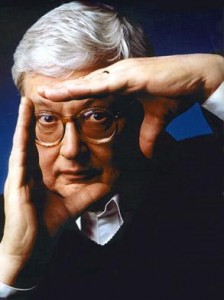

Certainly in his career and the people he came to know, Roger Ebert was incredibly lucky, as he himself admits. Although, early on, attending high school, he felt he didn’t belong, he somehow took possession—quickly and decisively—of the intellectual, creative side of his life. He knew what he wanted to be: a writer.

Acquiring that little niche of film criticism, however, was the last thing on his mind. From the beginning, journalism was the objective. He printed a little neighborhood newspaper, the Washington Street News. He covered athletics for the Urbana High School paper, later announcing sports on the radio. At age fourteen, he interviewed Senator Estes Kefauver, and seven years later he had his first byline on the front page of the Chicago Sun-Times, a story about the violation of the freedom of speech. Soon after that, while attending the University of Cape Town, he would observe another version of injustice in apartheid.

As an avid reader, his favorite writers included Shakespeare, Dickens and Henry Miller. He writes that there was no pattern to his early reading. “The great influence was Thomas Wolfe, who burned with the need to be a great novelist, and I burned in sympathy. I felt that if I could write like him, I would have nothing more to learn.”

It was only a bit later that he got into the “movie business,” reviewing his first movie, the French film Galia, directed by Georges Lautner, for the Sun-Times. In 1967, he became the paper’s film critic. “I’d never have made a competent academic,” Roger writes, and the way was open for a new direction for his writing drive. “It was a honey of a job to have at that age. I had no office hours; it was understood that I would see the movies and meet the deadlines. I loved getting up from my desk and announcing, ‘I’m going to the movies.’ ”

It was only a bit later that he got into the “movie business,” reviewing his first movie, the French film Galia, directed by Georges Lautner, for the Sun-Times. In 1967, he became the paper’s film critic. “I’d never have made a competent academic,” Roger writes, and the way was open for a new direction for his writing drive. “It was a honey of a job to have at that age. I had no office hours; it was understood that I would see the movies and meet the deadlines. I loved getting up from my desk and announcing, ‘I’m going to the movies.’ ”

From there the rest seemed to come naturally, but always with a lot of drive. He began interviewing Lee Marvin, Sophia Loren, Ingmar Bergman, Robert Altman, Werner Herzog and Robert Mitchum, and making friends of many of them. On-the-job training, in lieu of a formal film education, he observes, was “possibly more useful.” He wasn’t afraid to ask questions; the directors became, to use his term, his “teachers,” men like Norman Jewison, Peter Collinson and Richard Brooks. “ . . . when I asked, they actually sketched out shots on a piece of paper and told me what they were trying to do, and why. . . . They seemed to have an instinct for teaching, and I soaked it in.”

Roger was the first person to receive a Pulitzer Prize for film criticism, in 1975, the year he started a long TV association with Gene Siskel in the movie review show Siskel and Ebert. The program, with one title or another, continued until Gene’s death in 1999. Under still another label, Ebert Presents at the Movies, the current program has two regular critics, ensconced on a balcony as in the previous formats, with a voice reading Roger’s film reviews.