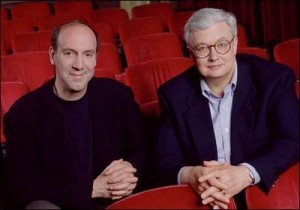

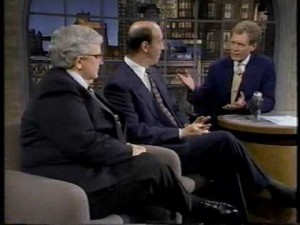

Gene and Roger were quite different in many ways—Gene, for one, was secretive; Roger regards himself as forthright, ready to blurt out whatever is on his mind—but they were also much alike, highly competitive and prone to flaring arguments, so much so that when they appeared on Johnny Carson, they were scrupulous, from visit to visit, to alternate who sat next to Johnny.

Gene and Roger were quite different in many ways—Gene, for one, was secretive; Roger regards himself as forthright, ready to blurt out whatever is on his mind—but they were also much alike, highly competitive and prone to flaring arguments, so much so that when they appeared on Johnny Carson, they were scrupulous, from visit to visit, to alternate who sat next to Johnny.

“We both thought of ourselves,” Roger writes, “as full-service, one-stop film critics. We didn’t see why the other one was necessary.” And yet—and yet, Roger writes, “Gene died on February 20, 1999. He’s in my mind almost every day. He became less like a friend than like a brother.”

“We both thought of ourselves,” Roger writes, “as full-service, one-stop film critics. We didn’t see why the other one was necessary.” And yet—and yet, Roger writes, “Gene died on February 20, 1999. He’s in my mind almost every day. He became less like a friend than like a brother.”

Besides the tragedy of Gene’s death and Roger’s still precarious health—Roger poignantly writes “I will die sooner than most of those reading this”—there were other dark shadows in his life. His father was an alcoholic, as his mother would become after his dad’s death. Abhorring personal confrontations, Roger left home rather than face, as he said, his mother’s “emotionalism.” His parents’ influence was obvious and Roger became an alcoholic himself.

“My alcoholism was masking deep problems, but it was a dependable friend, always there, never critical, making me feel good after it made me feel bad, so that I could sing and joke with a raucous crowd of newspaper friends and Old Town characters, forming those undying barroom friendships that never survived outside a bar.” (One of Roger’s rare long sentences.) He knew he had problems, joined AA and took his last drink in 1979.

“My alcoholism was masking deep problems, but it was a dependable friend, always there, never critical, making me feel good after it made me feel bad, so that I could sing and joke with a raucous crowd of newspaper friends and Old Town characters, forming those undying barroom friendships that never survived outside a bar.” (One of Roger’s rare long sentences.) He knew he had problems, joined AA and took his last drink in 1979.

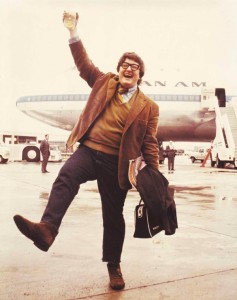

There are many interesting, well-written moments in this memoir. London being perhaps his favorite city, Roger writes wistfully of his walks about that great city. Through St. James’ Park. A stop at Sims, Reed & Fogg, the antiquarian booksellers. A visit to Kenwood House, “the grandest country house near London,” with its Rembrandts and Romneys. To the graves of Karl Marx and George Eliot in, Roger is careful to point out, the New Highgate Cemetery, not the Old. And the Eyrie Mansion on Jermyn Street, a seventeenth-century hotel where he stayed on his London visits. The hotel was run by Henry Togna, who, Roger writes colorfully, “appears in a Dickens novel I haven’t yet read.”

As someone has said, possibly Mark Twain, when we long for the “good old days” long ago, we actually long for our youth. In my own memories, I know London will have changed for me since I was last there in my relative youth, but there is also Roger’s warning, equally wrapped in nostalgia:

“For twenty-five years I was to come to 22 Jermyn Street time and time again. Now I can never return. Some obscene architectural extrusion will rise upon the sacred land, some eyesore of retail and condos. Piece by piece, this is how a city dies. How many cities can spare a hotel built in 1685, the year James II took the crown?”

Even without returning, I can see just from films that modern, tall buildings have destroyed the skyline of London—and that glass pyramid the dignity of the Louvre. Yes, Roger Ebert has a sense of the nostalgic and also, what is rare in many writers, the genius to convey it—about London, yes, but toward the end of his book he touches a little deeper, about finding the love of his life, his wife Chaz, about his numerous operations, many unsuccessful, about his fiftieth high school reunion and maybe that possible last return to Urbana, Illinois, and, perhaps most moving, about his views on life and God, which seem independent and rational, despite his Catholic upbringing.

Chapter 54, “How I Believe in God,” is a must-read. His reasoning, simply expressed, is so logical, in his mind and probably in many of his readers’, as to seem incontrovertible, especially his view of mankind’s desperate need to believe in some higher being and the “sociopolitical, not spiritual megachurches with [their] jocular millionaire pastors.” His belief, however, that it’s “easier for a Republican to pass through the eye of a needle than for a camel to go to heaven” is a bit harsh!

Life Itself: A Memoir—all of it—is a must-read. There is very little about movies themselves—more about movie people Roger has known and knows—for this is, after all, an autobiography, a full, adventuresome life, and much more, vividly conveyed. A respect for, and appreciation of, other people gives this memoir its warmth, mainly because people are important to Roger.

Life Itself: A Memoir—all of it—is a must-read. There is very little about movies themselves—more about movie people Roger has known and knows—for this is, after all, an autobiography, a full, adventuresome life, and much more, vividly conveyed. A respect for, and appreciation of, other people gives this memoir its warmth, mainly because people are important to Roger.

What I must repeat is the easy readability of the prose, the often quiet eloquence. There are, too, those subtle mechanics of writing which shouldn’t be overlooked. Somewhere around mid-point in my reading, I was struck that I didn’t recall seeing any dashes! Upon checking, though, I found a few, very few. Maybe it’s something of a feat to write so well without the possible “crutch” of the dash—something some writers can’t do without.

Before I knew it appeared on the back of the dust cover, I had found this treasure in the text, maybe Roger’s summation of his life: “I believe that if, at the end, according to our abilities, we have done something to make others a little happier, and something to make ourselves a little happier, that is about the best we can do. To make others less happy is a crime. To make ourselves unhappy is where all crime starts.”