Catch me if you can!

Director James Whale, like any number of movie personalities, lived his own variation of a distressed life.He started his career in his native Britain with a now obscure film, Journey’s End, what would later be termed, as time would prove, an atypical effort. Two years and four films later Colin Clive, the star of Journey’s End, would resurface in what, indeed, would be a typical Whale film, Frankenstein, a masterpiece of its kind.It would launch the career of Boris Karloff as the monster. In what would become a trademark, Whale treated the creature sympathetically and added humor to the plot.Stark and frightening at times, the film’s most serious shortcoming is the lack of a musical score.

Karloff continued as a Whale star in two subsequent films of like spirit. The Old Dark House (1932) is about a group of travelers isolated in a strange house during a thunderstorm.Besides Karloff, the stellar cast includes Melvyn Douglas, Gloria Stuart, Ernest Thesiger, Charles Laughton and Raymond Massey.

In 1935, emerging from Whale’s macabre imagination, came The Bride of Frankenstein, with Clive and Thesiger returning, now aided by Elsa Lanchester, John Carradine, E. E. Clive and Whale favorite Una O’Connor.Here was even more humor, most famously in Doctor Pretorius’ “little people,” and any musical deficiencies were amended by Franz Waxman’s milestone score.

Not a horror film as such though with touches of one, The Man in the Iron Mask (1939) was Whale’s last film of any merit, although there would be three more. Bereft of the usual cast of Whale’s favorite actors, the film did have Peter Cushing in his film début in a small part and, despite his versatility, the typecast Dwight Frye continued in like vein after Dracula, Frankenstein, The Bride of Frankenstein and The Vampire Bat. There were also Louis Hayward, Joan Bennett, Warren William, Joseph Schildkraut and Alan Hale.

But—and here comes the beginning of Whale’s “distress”—when he lost control of film and script at Universal, he left the movies in 1949, beginning eight years of isolation and creative stagnation before his death.

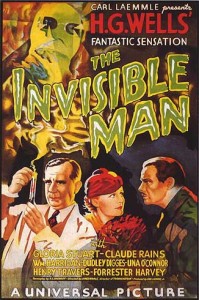

Back in his glory days, however, when Whale had overnight become the master director of horror films, The Invisible Man (1933) was the third of his quartet of great horror films. Although the least original of the four, the special effects are quite impressive for their time. True, the sometimes visible wires that move objects and guide a bicycle over an obvious pre-arranged path are less remarkable, but what is impressive is the faceless Jack Griffin ([intlink id=”604″ type=”category”]Claude Rains[/intlink] in his sound film début) when he removes his bandages or sheds his clothes from an invisible body.

Back in his glory days, however, when Whale had overnight become the master director of horror films, The Invisible Man (1933) was the third of his quartet of great horror films. Although the least original of the four, the special effects are quite impressive for their time. True, the sometimes visible wires that move objects and guide a bicycle over an obvious pre-arranged path are less remarkable, but what is impressive is the faceless Jack Griffin ([intlink id=”604″ type=”category”]Claude Rains[/intlink] in his sound film début) when he removes his bandages or sheds his clothes from an invisible body.

In the first shot of the film a man is trudging through the snow with a suitcase. Dr. Griffin takes a room at the Lion’s Head and, right away, abuses the owners (Forrester Harvey and an hysterical Una O’Connor) when they interrupt his chemical experiments and the policeman (a mumbling E. E. Clive) when he tries to arrest the mysterious guest.

“A way back. A way back to visibility.There must be a way back,” Griffin tells his girlfriend Flora (a demure Gloria Stuart prone to tears) and fellow scientist Kemp (a rather hammy William Harrigan) whom he recruits as his reluctant partner. “We’ll begin with a reign of terror,” Griffin tells him, “—a few murders here and there, murders of great men, murders of little men, just to show we make no distinction.”

“A way back. A way back to visibility.There must be a way back,” Griffin tells his girlfriend Flora (a demure Gloria Stuart prone to tears) and fellow scientist Kemp (a rather hammy William Harrigan) whom he recruits as his reluctant partner. “We’ll begin with a reign of terror,” Griffin tells him, “—a few murders here and there, murders of great men, murders of little men, just to show we make no distinction.”

Flora’s father, Dr. Cranley (a steady rock in Henry Travers), warns her that Griffin has taken a drug that has driven him insane, that he must be rehabilitated.In one of Jack’s—and Rains’—best speeches, beginning quietly in rational tones and gradually building to hysterical madness, he cries, “Even the moon’s frightened of me, the whole world frightened to death.”

In phoning Flora and her father to come when Griffin has imprisoned him in his own house, Kemp has also alerted the police. After vowing to murder Kemp the next night for his betrayal (why not then and now?), Griffin eludes the police and wreaks a small panic on the countryside—killing, robbing and derailing a train. (The shots of moving, unmanned switch levers and a model train careening down a cliff and splashing into a river would be reused almost ten years later in Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror.)

Skipping down a road, with only a pair of trousers and shirt visible, he laughs and sings,“Here we go gathering nuts in May,/Nuts in May, nuts in May,/Here we go gathering nuts in May,/On a cold and frosty morning.”