An hilarious study in the gentle art of murder.

The British, God bless ’em, are known for their wit, a distorted and sometimes droll wit to many Americans, who don’t always appreciate the extremes of their brand of humor, from subtle double-entendre to farcical broadness.

In the late 1950s, early ’60s, there were the Hoffnung Concerts in which highbrow composers and performers caricatured their own classical music—for example, Malcolm Arnold’s Concerto for Three Vacuum Cleaners and a Floor Polisher. At about the same time the wacky world of Beyond the Fringe erupted to hilarious acclaim in London’s West End and spread to the U.S. All the satire and lampooning of, especially, the arts was thanks to a quartet of comic masters known as Jonathan Miller, Alan Bennett, Dudley Moore and Peter Cook. And then, on BBC TV and later in the movies, there was Monty Python, where comedy became surreal, preposterous, cruel and, yes, sometimes offensive. In this troupe were more than four players, but the best-remembered, the most enduring, are John Cleese and Eric Idle.

For those who would belittle British humor, forget not that many of the most famous of so-called “American” comics and teams—some of them institutions—were wholly, or partly, British: Bob Hope, Laurel and Hardy and Charlie Chaplin.

As America’s Hollywood once held sway, say, in the detective and horror movies, so the British are still masters of the comedy, and turn out more of that genre than their cousins across the Atlantic. Foremost was the “Carry On” series, over thirty low-budget films released between 1958 and 1992, an enterprise dealing in parody, sexual innuendo and the ridicule of the British establishment. The three stars who appeared most frequently throughout the years—Kenneth Williams, Joan Sims and Charles Hawtrey—also performed in conceivably the epitome of the series, Carry On Doctor, with another regular, Barbara Windsor, in another of the scantily-clad roles she made all her own. In this sense, too, the British seemed far ahead of the Americans during the ’50s and ’60s in “coming out” roles for young actresses!

Some British comedies that would be better known to Americans, along with at least one well known star, include The Ghost Goes West (Robert Donat), The Ladykillers (Alec Guinness), A Mouse on the Moon (Margaret Rutherford), Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (Terry-Thomas) and A Fish Called Wanda (Cleese). In more recent releases, the diversity of British humor is further illustrated in Four Weddings and a Funeral, The Full Monty and Chicken Run.

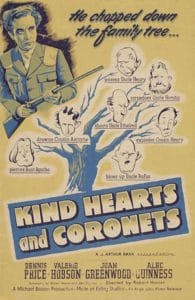

To mention for the first time the intent of all this, there was Kind Hearts and Coronets in 1949, a little masterpiece all its own, a one of a kind. Here, droll humor is at its height, an analytical but comic approach to one of the darker of man’s sins, murder. Even as a school child (Jeremy Spenser), the “hero” and narrator of the story was early on made aware, specifically, of two of the Ten Commandments, two that just happen to be adjacent, the one about not killing, the other about not committing adultery. With already an eye for the little girl next to him, he commented that, at least, he didn’t foresee that he would ever have to worry about the first! A small matter, perhaps.

To mention for the first time the intent of all this, there was Kind Hearts and Coronets in 1949, a little masterpiece all its own, a one of a kind. Here, droll humor is at its height, an analytical but comic approach to one of the darker of man’s sins, murder. Even as a school child (Jeremy Spenser), the “hero” and narrator of the story was early on made aware, specifically, of two of the Ten Commandments, two that just happen to be adjacent, the one about not killing, the other about not committing adultery. With already an eye for the little girl next to him, he commented that, at least, he didn’t foresee that he would ever have to worry about the first! A small matter, perhaps.

There is little in American letters to compare with the often tongue-in-cheek wit, the polished absurdities, of King Hearts and Coronets, certainly not in Poe, whose tales are devoid of humor, nor in the disguised social commentary of Twain’s most famous novels. Rather, the delightful adaptation of Roy Horniman’s novel by screenwriters Robert Hamer (also the director) and John Dighton owes, logically enough, much to one cherished niche of the British literary tradition—the drawing room drama, specifically the writings of Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw and P. G. Woodhouse. Although the link of murder is there, the formula mysteries of Christie are not an influence; they, too, are usually bereft of humor.

On to the plot of Kind Hearts and Coronets——

On to the plot of Kind Hearts and Coronets——

In a prison in Edwardian England, a hangman (Miles Malleson, playing another of his befuddled roles, jowls quivering) arrives to visit what Americans would call the warden (Clive Morton) to see if everything is ready for tomorrow, and to ascertain how to address properly the condemned at the scaffold ceremonies. “Your grace,” he decides, is correct. Louis Mazzini (Dennis Price), if for only the briefest time the Duke of Chalfont, is waiting to be hanged. In the meantime he’s writing his memoirs.

As he writes in his cell, clad in evening jacket, his previous life unfolds in flashback, accompanied by his calm, orderly and dispassionate narration, complete with axioms and genteel social observations. Seems the real source of his predicament began when his mother eloped with an Italian opera singer (also played by Price), and thus a bit of an aria from Mozart’s Don Giovanni. For marrying beneath her station, she is subsequently disowned by her aristocratic family, the D’Ascoynes.

For this insult to his mother, Mazzini vows revenge on the D’Ascoynes, to eliminate, one by one, the eight individuals who stand between him and the dukedom. He keeps a tally of his victims on the family tree, glued to the back of a landscape painting.

For this insult to his mother, Mazzini vows revenge on the D’Ascoynes, to eliminate, one by one, the eight individuals who stand between him and the dukedom. He keeps a tally of his victims on the family tree, glued to the back of a landscape painting.

While Mazzini is reduced to being a draper’s assistant, he by chance waits on the snotty Ascoyne D’Ascoyne (Alec Guinness). To begin what today would be called the crimes of a serial killer, Louis swims the river to a little rowboat where D’Ascoyne and his mistress are enjoying a tryst and unties the mooring line. The boat gently floats away and, far downstream, stern up, drops off a waterfall.

The second victim is Henry D’Ascoyne (Guinness again), an amateur photographer. While Mazzini easily shares tea in the garden with Henry’s wife, Edith (Valerie Hobson), the photographer is off developing his latest film. The night before Mazzini had replaced one of the developing chemicals with petrol. During a shot of Mazzini, an explosion is heard off camera. He comprehends the sound but remains calmly attentive to Edith. With the change to a shot of just her, a haze of smoke appears above a wall in the distance. At first neither notices the dark plume, which grows gradually larger as they talk idly.

The second victim is Henry D’Ascoyne (Guinness again), an amateur photographer. While Mazzini easily shares tea in the garden with Henry’s wife, Edith (Valerie Hobson), the photographer is off developing his latest film. The night before Mazzini had replaced one of the developing chemicals with petrol. During a shot of Mazzini, an explosion is heard off camera. He comprehends the sound but remains calmly attentive to Edith. With the change to a shot of just her, a haze of smoke appears above a wall in the distance. At first neither notices the dark plume, which grows gradually larger as they talk idly.

When Mazzini does see the smoke—she hasn’t yet—he continues sipping his tea, and after Edith asks him how he could help broaden her husband’s limited activities, Mazzini’s voice-over narration drolls: “I could hardly point out that Henry and I had no time left for any kind of activity, so I continued to discuss his future.” This is one of the funniest moments in the film, perhaps because the explosion is heard and not seen, the smoke is so obvious to the viewer and, at the same time, so unnoticed and ignored by the two blasé characters, plus the equally indifference of the music track—there is no music.

Attending Henry’s funeral, Louis has the chance to view all the D’Ascoyne family, his six future victims: the vicar, “talking interminable nonsense” from the pulpit; Lady Agatha, a suffragette; a bald-headed, dozing general; an admiral, first name Horatio, of course; Ethelred, the hunter of the family; and his lordship, a banker—all played, as has been implied earlier, by Guinness. During the camera pan from one character to another, especially when on the general and the admiral, the score suggests a Gilbert and Sullivan patter song, say, from The Pirates of Penzance. This bit of music will be expanded in the end cast.

Two of Mazzini’s potential victims—the admiral, who fortuitously drowns in a naval accident, and the banker, who dies of a stroke—escape any premeditated death. But ironically Louis has landed in prison for a murder he did not commit, that of Lionel Holland (John Penrose), who had married Mazzini’s paramour, Sibella (the ebony-voiced Joan Greenwood, never lovelier).

In fact, during the flashbacks Mazzini carries on with both Sibella and Edith. As he observes, “For, while I never admired Edith as much as when I was with Sibella, I never longed for Sibella as much as when I was with Edith.” Some of Price’s love scenes with Greenwood were quite sensational for their time. The cause for any concern at all is quite inexplicable by today’s standards, because, for one, they were both fully clothed. For another, the elegant Edwardian dresses covered, from head to toe, even arms most of the time, any possibly provocative flesh!

At the last minute, Lionel’s suicide note is discovered. Sibella, who had withheld it, produced the evidence once Mazzini had agreed to get rid of Edith, who, in the course of things, he had married. So, is he off, scot-free? What of his memoirs detailing his activities against the D’Ascoyne family? Where are they? Has he remembered them? Therein lies a twist in this little tale’s ending, the one thing, perhaps, not to be revealed here.

At the last minute, Lionel’s suicide note is discovered. Sibella, who had withheld it, produced the evidence once Mazzini had agreed to get rid of Edith, who, in the course of things, he had married. So, is he off, scot-free? What of his memoirs detailing his activities against the D’Ascoyne family? Where are they? Has he remembered them? Therein lies a twist in this little tale’s ending, the one thing, perhaps, not to be revealed here.

Unlike Ernest Irving’s rather sporadic score, Douglas Slocombe’s cinematography gives the picture an extra touch of sophistication and elegance that seems to soften, even make funnier by contrast, the film’s subject matter. One example is Mazzini and Edith’s scene in the spacious salon soon after Henry’s funeral, when Mazzini proposes to her, at first in vain. Much of the scene is done in one take, even when she rises from the sofa and walks away in a long shot and returns to sit down. Many scenes are handled in this way, the cutting throughout reduced to a minimum.

A favorite photographer of Steven Spielberg and cameraman for John Huston’s Freud and Anthony Harvey’s The Lion in Winter, Slocombe did, however, have to contend with some poor rear projection and some tacky sets, including a street scene for the arrest of dear old Agatha. The little ship models in a tank of water, preceding the demise of Admiral D’Ascoyne, are the crudest imaginable.

The deaths of four victims transpire fairly quickly—the admiral in a ship collision, the general from an exploding jar of caviar, the banker from a stroke and Agatha in a plummeting hot air balloon. As for the last, Mazzini said, “I shot an arrow in the air./She fell to earth in Berkeley Square.”

By contrast, the demise of the vicar and, as already related, the photographer are lingered over with British relish. My favorite of Guinness’ roles is that of the vicar. In a long and wonderfully unhurried scene, Mazzini has disguised himself as a visiting colonial bishop who has to endure the clergyman’s tedious tour of the church before poisoning his port at dinner. Mazzini even has to produce, on the vicar’s insistence, an example of the dialect of the Metabealliac tribe which Mazzini unwisely fabricates to make his character more convincing. The resulting grunts, burps and gurgles leave the vicar perplexed—and sorry he insisted.

Giving perhaps his best performance in Kind Hearts and Coronets, Dennis Price had a long and varied career, entering television as early as the mid-’50s. TV was due not so much to any “specializing” as it was to being “reduced” to it. Unfortunately, the actor had many personal problems—alcoholism, drug abuse, gambling and homosexuality, although he fathered two children during an eleven-year marriage and had affairs with his leading ladies. For much of his career, then, he played in a multitude of horror films and many “B” films, often in cameo roles. He possibly had cirrhosis of the liver when he died in 1973, ostensibly from a heart attack following a hip fracture, the result of a fall in his home in the Channel Islands.

Although Price dominates the movie with his cold yet urbane acting and narration—the narration is a key part of his, and the movie’s, appeal—it is Alec Guinness who is the most fascinating, who keeps the viewer on alert, perhaps even distracting him. Where will Alec turn up next, and how will he appear? Guinness, who tackled the film enthusiastically, was first offered four of the D’Ascoyne roles but insisted on playing all eight.

As Ascoyne D’Ascoyne, the photographer and the hunter, who, of course, dies in a tragic shotgun “accident,” Guinness is easily recognizable. But as the general, demonstrating his greatest victory on a restaurant table, he wears a skull cap and speaks in a raspy, nasal voice. As the admiral, crying “bring her to port” when his first mate asks, “Don’t you mean ‘starboard,’ sir?,” he’s all hair and beard. In drag as Agatha, the actor disappears in make-up and dress. And as the elderly clergyman, Guinness dons a white wig, a stoop, an unsteady gait, quivering hands and a crackly voice.

As Ascoyne D’Ascoyne, the photographer and the hunter, who, of course, dies in a tragic shotgun “accident,” Guinness is easily recognizable. But as the general, demonstrating his greatest victory on a restaurant table, he wears a skull cap and speaks in a raspy, nasal voice. As the admiral, crying “bring her to port” when his first mate asks, “Don’t you mean ‘starboard,’ sir?,” he’s all hair and beard. In drag as Agatha, the actor disappears in make-up and dress. And as the elderly clergyman, Guinness dons a white wig, a stoop, an unsteady gait, quivering hands and a crackly voice.

In filming two of the characters, he came close to disaster. As the admiral, saluting as the churning water rises above his head and floats away his cap, his feet were secured to the bottom of the water tank set. Only after the scene was filmed did someone remember the actor hadn’t been untied and was freed just in time. As Agatha, Guinness refused to go up in the hot air balloon, feeling the insurance coverage wasn’t enough. Another man assumed Agatha’s disguise and boarded the balloon, only to be whisked away in a sudden breeze, some fifty miles, and dumped in a river. This is the accepted account, but from what is seen on screen, there’s little evidence that the balloon rose very high or even left the set.

The two-disc Criterion Collection features both versions of Kind Hearts and Coronets. Two versions? Yes, the original British and the American. Back when, that Hollywood custodian of morality, the Hays Office, censored some of the scenes between Price and Greenwood to soften the adultery, deleted the “n” word in the “Eeny, meeny, miny, moe” children’s rhyme and “clarified” the ending to make it clear Mazzini did pay for his crimes. Also, the British version and the American alternative ending have been released in Britain on Blu-ray by StudioCanal UK.

The two-disc Criterion Collection features both versions of Kind Hearts and Coronets. Two versions? Yes, the original British and the American. Back when, that Hollywood custodian of morality, the Hays Office, censored some of the scenes between Price and Greenwood to soften the adultery, deleted the “n” word in the “Eeny, meeny, miny, moe” children’s rhyme and “clarified” the ending to make it clear Mazzini did pay for his crimes. Also, the British version and the American alternative ending have been released in Britain on Blu-ray by StudioCanal UK.

And the title of the movie? It comes from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem, Lady Clara Vere de Vere (1833):

Howe’er it be, it seems to me,

’Tis only noble to be good.

Kind hearts are more than coronets,

And simple faith than Norman blood.

Perhaps the movie audiences have come to accept, if only subliminally, that Louis Mazzini is the calmest, most stylish of murderers, and, so, a last word from him: “The next morning I went out shooting with Ethelred, or, rather, to watch Ethelred shooting, for my principles will not allow me to take a direct part in blood sports.”

This is another film I’ll have to check out. I think my husband would really enjoy this.

I laughed when you mentioned the Carry On gang. I watched their movies when I was a young teenager; a local television station ran them late Saturday nights and I would catch them while I was babysitting. I haven’t seen one of these movies since, but everything I read says a LOT of the material went over my head! It would be interesting to see them again from the perspective of an adult.

Interesting comments above. I first saw this masterpiece in the 1950s at the MFIS(Merseyside Film Institute Society). I have seen it many times since and still marvel at the performances of all concerned. It is the only film ever to contain every kind of humour – wit, repartee, epigram, satire, parody, sarcasm, irony(both kinds – verbal and dramatic) and any other kind that you can think of. You mention some of the tacky sets but you missed out the dreadful one where Dennis Price is standing at the graveside of his mother. I cringe every time I watch it! No matter. Query: When the General is blown apart at the dinner table, what happened to his (blameless) companions? Bit over the top, what?