“Badges? We ain’t got no badges. We don’t need no badges. I don’t have to show you any stinking badges.” — Gold Hat (Alfonso Bedoya) to the prospectors

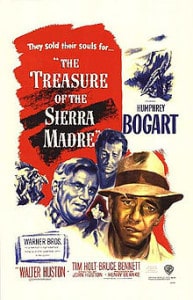

Unlike some of John Huston’s films that were done for the money, or as a relaxing diversion or to mark time until something better came along, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was one of those special projects the director had long had in mind. Other similar passions include his first film for Warner Bros., the 1941 version of The Maltese Falcon, later Moby Dick and The Man Who Would Be King. Besides fulfilling his predilection for themes on hard-fought battles lost or the disillusion of life, in Treasure he foresaw a great role for his father, Walter, as the toothless, grizzled old prospector.

As so often with Huston, getting started on a film, or even surviving once started, was an ordeal in itself, even when he wasn’t imposing challenges and the nearly impossible on himself. As if, for example, the hostile location of darkest Africa wasn’t enough during The African Queen, he returned a few years later for The Roots of Heaven. “The location,” he wrote in his autobiography, An Open Book, “was one of the most difficult I have ever been on.” Worse than Queen? He knew Katharine Hepburn could vouch for that ordeal; she even wrote a book about it!

There were other similar situations. Desaturating and tinting the color, and otherwise giving the Moulin Rouge a monochromatic hue, prompted Technicolor officials to refute any responsibility for the outcome. For Moby Dick, there were no less than three accursed mechanical whales, one breaking its moorings and becoming a sea hazard; and, according to Huston, he almost lost his lead actor, Gregory Peck, during filming. And then there were the temperamental, mentally unstable and alcoholic stars whom Huston took on knowingly, almost as a challenge: Marilyn Monroe, Montgomery Clift and Errol Flynn. Huston, who knew Errol was dying from alcohol and drug abuse, wrote that he didn’t regret taking him along on The Roots of Heaven: “[Flynn] said afterward that he’d not had such a good time in years.”

The director, who could be a man of fathomless benevolence—he loved animals, adopted a Mexican orphan—was also a wicked practical joker. When he received his World War II assignment as a documentary film maker, he had almost finished Across the Pacific, about a Japanese plan to attack the Panama Canal—a reuniting of [intlink id=”189″ type=”category”]Humphrey Bogart[/intlink], Mary Astor and Sidney Greenstreet from The Maltese Falcon. In the last scene he directed before his departure, he filmed Bogart as a tied up prisoner, guarded by a throng of Japanese soldiers. It was up to his replacement director, Vincent Sherman, to figure how to extricate the hero.

The director, who could be a man of fathomless benevolence—he loved animals, adopted a Mexican orphan—was also a wicked practical joker. When he received his World War II assignment as a documentary film maker, he had almost finished Across the Pacific, about a Japanese plan to attack the Panama Canal—a reuniting of [intlink id=”189″ type=”category”]Humphrey Bogart[/intlink], Mary Astor and Sidney Greenstreet from The Maltese Falcon. In the last scene he directed before his departure, he filmed Bogart as a tied up prisoner, guarded by a throng of Japanese soldiers. It was up to his replacement director, Vincent Sherman, to figure how to extricate the hero.

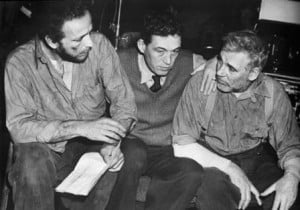

The novel The Treasure of the Sierra Madre by the mysterious recluse B. Traven, originally published in German in 1927, waited on the shelf until Huston’s return from the war. The screen transfer was the first American film made on location outside of the U.S., if not entirely then in large part, mainly in Tampico and Jungapeo, Mexico. Huston and friend, his occasional producer, Henry Blanke, convinced Warners head, Jack Warner, that the project was viable. The Mexican pre-production work was done with a stand-in for Bogart, followed by location filming with the stars. In between and afterward came the studio work—interiors and campfire scenes, the gunfight with the bandits.

From Traven’s treatise on greed and corruption, Huston in his screenplay eliminated the anti-capitalist, anti-church elements and concentrated on the greed and general foibles of the three main characters. The old prospector, Howard ([intlink id=”293″ type=”category”]Walter Huston[/intlink]), understands greed, even predicts inadvertently what will happen to the trio after they form their partnership. “I know,” he says, “what gold does to men’s souls.” Almost as an observant bystander, he finds something more important than gold when saving an unconscious Mexican boy, and is taken into the group as a highly regarded personage.

From Traven’s treatise on greed and corruption, Huston in his screenplay eliminated the anti-capitalist, anti-church elements and concentrated on the greed and general foibles of the three main characters. The old prospector, Howard ([intlink id=”293″ type=”category”]Walter Huston[/intlink]), understands greed, even predicts inadvertently what will happen to the trio after they form their partnership. “I know,” he says, “what gold does to men’s souls.” Almost as an observant bystander, he finds something more important than gold when saving an unconscious Mexican boy, and is taken into the group as a highly regarded personage.

But Howard, too, is tainted. Though easily the most likeable of the trio—and Walter Huston’s is the most captivating performance—his dark side emerges when he agrees with his partners to kill a stranger (Bruce Bennett) who wanders into the camp and demands a share of their gold. Before that plan can be executed, however, the interloper dies in a gunfight with the bandits who had previously attacked a train. The film’s most famous line occurs just before the showdown: “I don’t have to show you any stinking badges,” spoken by Gold Hat, the leader of the bandits, a popular Mexican actor, Alfonso Bedoya, of the time.

The initially naïve member of the trio is Bob Curtin (Tim Holt), a sentimentalist, it seems, who reminisces about picking peaches and, at film’s end, decides to seek out the stranger’s widow. He also is touched by evil. When the mine caves in on the third partner, Fred C. Dobbs (Bogart), Curtin first rushes toward the entrance. But just when his quiet, passive persona suggests he might be the decent one of the bunch, he stops and turns away, thinking of Dobbs’ share of the gold that might be his. Moments later, however, he turns back to save Dobbs.

Almost from the first, Dobbs has the smell of duplicity, and is slightly unlikable, without conveying any sense as to why. He wanders the streets of Tampico, panhandling. Three times from the same white-suited American (an uncredited John Huston) he receives some pesos, enough to buy a lottery ticket from an urchin (a 15-year-old Robert Blake) and have a shave and haircut.

Almost from the first, Dobbs has the smell of duplicity, and is slightly unlikable, without conveying any sense as to why. He wanders the streets of Tampico, panhandling. Three times from the same white-suited American (an uncredited John Huston) he receives some pesos, enough to buy a lottery ticket from an urchin (a 15-year-old Robert Blake) and have a shave and haircut.

Soon after Dobbs meets Curtin in a park, the two happen to rent their beds next to Howard in a flophouse. In one of his best scenes, Howard philosophizes about mining for gold. After suggesting going alone as one option, though the loneliness can drive a man crazy, he says, “Going with a partner, too, is dangerous. Murder’s always lurking about, partners accusing each other of all sorts of crimes.”

Later, Dobbs and Curtin are hired by a foreman (Barton MacLane) to build a derrick, with the promise of pay when the job is done. Of course payment never comes. Later Dobbs and Curtin follow him to a bar and take their money, but not before a three-man brawl, one of the most realistic—and bloodiest—ever filmed at the time. Its authentic brutality came from director Huston, who not only had been a member of the Mexican cavalry, a bullfighter and an art student, but also a boxer. Huston even made a film, Fat City in 1972, about two down-and-out warriors of the ring.

Later, Dobbs and Curtin are hired by a foreman (Barton MacLane) to build a derrick, with the promise of pay when the job is done. Of course payment never comes. Later Dobbs and Curtin follow him to a bar and take their money, but not before a three-man brawl, one of the most realistic—and bloodiest—ever filmed at the time. Its authentic brutality came from director Huston, who not only had been a member of the Mexican cavalry, a bullfighter and an art student, but also a boxer. Huston even made a film, Fat City in 1972, about two down-and-out warriors of the ring.

The two men seek out Howard, and despite the old man’s earlier warnings, they form a partnership, with Howard as guide for the two novices. By pooling their money—Dobbs conveniently wins the lottery, making up their shortfall—the men buy the necessary equipment and burros, and head up the mountain. Right off, after suffering through a sandstorm, Curtin and Dobbs think they have found gold; it’s pyrite, fool’s gold, Howard says. When his two partners are exhausted and suggest turning back, Walter Huston does his famous little jig, laughing and dancing as he tells them, “You’re so dumb, there’s nothin’ to compare you with. You’re dumber than the dumbest jackass . . . You’re so dumb you don’t even see the riches you’re treading on with your own two feet.”

Before long—there are hints of it from the first—Dobbs’ paranoia becomes obvious, then uncontrollable, this about ninety minutes into the film. While Howard is away one night being honored by the Indians for saving the little boy, his two partners are sitting around the campfire. Dobbs begins rocking back and forth and laughing sinisterly, saying they should steal the old man’s “goods.” When Curtin says he respects Howard’s gold as much as he would respect Dobbs’ if he were away, Dobbs calls him a liar and pulls a gun. He forces Curtin back into the jungle and shoots him.

The Indians find Curtin, wounded but alive. Howard takes care of him and then is off to the Indians again, to enjoy the lavish attention—a permanent siesta in a hammock, endless tequila and lovely señoritas.

Meanwhile, Dobbs, alone, face encrusted with dust and dirt, staggers with the burros to a water hole. In a reflection in the water, he sees a sombreroed face. It’s Gold Hat, malicious and sinister. As Dobbs tries to convince the toothy bandit that his partners are right behind him, the outlaws try on Dobbs’ hat, examine his boots and clothes. Their intent is obvious, and Gold Hat kills Dobbs—discreetly obscured by a burro—with two whacks of his machete.

Meanwhile, Dobbs, alone, face encrusted with dust and dirt, staggers with the burros to a water hole. In a reflection in the water, he sees a sombreroed face. It’s Gold Hat, malicious and sinister. As Dobbs tries to convince the toothy bandit that his partners are right behind him, the outlaws try on Dobbs’ hat, examine his boots and clothes. Their intent is obvious, and Gold Hat kills Dobbs—discreetly obscured by a burro—with two whacks of his machete.

The bandits rummage through the burros’ saddlebags, spilling the gold, presumably ignorant of its value, which seems a bit implausible. The bandits, one already changed into Dobbs’ clothes, are soon executed in the town when they try to sell the burros.

When Howard and Curtin learn of Dobbs’ death and gallop through another sandstorm to the saddlebags, they discover that all the gold dust has blown away. (In the novel, Traven allows the two men a few surviving bags, but John Huston’s screenplay is less generous.) After Howard starts laughing and Curtin joins in, the old man says, “Ah, laugh, Curtin old boy. It’s a great joke played on us by the Lord, or fate, or nature, whatever you prefer, but whoever, whatever played it certainly had a sense of humor. The gold’s gone back to where we found it.”

When Howard and Curtin learn of Dobbs’ death and gallop through another sandstorm to the saddlebags, they discover that all the gold dust has blown away. (In the novel, Traven allows the two men a few surviving bags, but John Huston’s screenplay is less generous.) After Howard starts laughing and Curtin joins in, the old man says, “Ah, laugh, Curtin old boy. It’s a great joke played on us by the Lord, or fate, or nature, whatever you prefer, but whoever, whatever played it certainly had a sense of humor. The gold’s gone back to where we found it.”

The role of Dobbs wasn’t the first negative character Humphrey Bogart had played since he broke free, in The Maltese Falcon, of his old gangster roles. In the recent past, there were the two wife killers in Conflict and The Two Mrs. Carrolls, both films and performances mediocre; and, later, there would be the paranoid Captain Queeg in The Caine Mutiny and the house invader in The Desperate Hours.

Departing further than ever before from the newly acquired persona of the debonair man, occasionally the romantic lead, Bogart renders a striking portrait in Treasure. Never grimier, never more devious and with the worst haircut of his career, he establishes a crescendo of deteriorating sanity, growing paranoia, hallucinations and menacing accusations. Huston thought it was the best performance of Bogart’s career. That’s the general assessment, but he was not even nominated for an Oscar.

Walter Huston, who had removed his false teeth when his son requested it, received the Supporting Actor Oscar. As the father famously said upon accepting his statuette, “Many, many years ago, I brought up a boy, and I said to him, ‘Son, if you ever become a writer, try to write a good part for your old man sometime.’ Well, by cracky, that’s what he did!” Warners executives, after seeing the rushes, had wired the director to tone down Walter’s performance. John Huston won Oscars for Director and Adapted Screenplay. The movie itself, some have felt since, was unfairly passed over for Best Picture by the “prestige” influences of Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet.

Walter Huston, who had removed his false teeth when his son requested it, received the Supporting Actor Oscar. As the father famously said upon accepting his statuette, “Many, many years ago, I brought up a boy, and I said to him, ‘Son, if you ever become a writer, try to write a good part for your old man sometime.’ Well, by cracky, that’s what he did!” Warners executives, after seeing the rushes, had wired the director to tone down Walter’s performance. John Huston won Oscars for Director and Adapted Screenplay. The movie itself, some have felt since, was unfairly passed over for Best Picture by the “prestige” influences of Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet.

An interesting footnote, John Huston films were on something of an Oscar roll. As Treasure was filmed in 1947 and released in January of 1948, he had time to direct another film that year, Key Largo, also with Bogart. The role of an intoxicated, pathetic mob moll won Claire Trevor the Supporting Actress Oscar at the same ceremonies in which Treasure won its three awards.

All that remains to be said—and an absolute necessity—is Max Steiner’s score, which adds a third dimension to the film. The music has been criticized for being Spanish, not Mexican. Small point. Treasure is one of Steiner’s finest scores, and to some degree atypical. True, he continues his tendency to borrow tunes from others, here appropriately using the Mexican folk song “El Desayuno,” among others. As source music, on two occasions at the campsite Howard plays “Those Endearing Young Charms” on his harmonica.

It’s often forgotten, that, like Richard Strauss, Mahler, Respighi and other so-called “serious” composers of the late nineteenth, early twentieth centuries, Steiner often scored for a large orchestra. This is especially true in Treasure, where the usual forces are augmented by two pianos, two vibraphones, glockenspiel, celesta, two harps, triangle and various suspended cymbals. Some of these instruments, especially, are used to represent the shimmer of gold, whether pyrite or real. And for that “Mexican” color—however Spanish it might be—Steiner adds guitars, mandolins, marimbas, an accordion and xylophones.

A small point, but it should be mentioned. Steiner was something of a master of choral writing—remember the slow, melancholy rendition of “Dixie” in Gone With the Wind behind “the land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields” frame?—and in Treasure Steiner employs a wordless choir when Howard is treating the little boy.

A small point, but it should be mentioned. Steiner was something of a master of choral writing—remember the slow, melancholy rendition of “Dixie” in Gone With the Wind behind “the land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields” frame?—and in Treasure Steiner employs a wordless choir when Howard is treating the little boy.

If not unique among Steiner’s scores, it certainly is a rarity that the main title of Treasure opens without the trademark fanfare that usually accompanies the Warner Bros. shield. Instead, the three-note “Mountain” motif, in a belligerent forte, immediately grabs the listener’s attention. The “Trek” theme, subject to many variations and key changes, plays a large part in the score. Its longest stretch, brilliantly orchestrated by Murray Cutter from Steiner’s detailed instructions, occurs when the prospectors begin their journey, with Howard leading the way through undergrowth and over rocks. This is when Dobbs observes how the old man seems to go without water, how he can climb, that he must be part camel, part goat.

For those who have and enjoy the Warners two-disc set of the film, which includes an extensive and well produced documentary on John Huston, the Naxos complete soundtrack CD is essential, well played by William Stromberg and the Moscow Symphony Orchestra and Chorus.

Treasure was certainly an unexpected film. Some would say it was an anomaly in the waning years of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Others would say that that age had already ended, some optimists that it had a few years to go, still others that it lingered in spurts, a picture here, a picture there, the isolated spasms of a dying era.

Treasure was certainly an unexpected film. Some would say it was an anomaly in the waning years of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Others would say that that age had already ended, some optimists that it had a few years to go, still others that it lingered in spurts, a picture here, a picture there, the isolated spasms of a dying era.

John Huston had created not only one of the great films of any time, but one of the most disturbing studies of greed, how the malady grows within what seems like normal individuals—whatever “normal” may be—how it possesses its owner, how it can even prove fatal, as it did for Fred C. Dobbs. More vivid, more encompassing, somehow more contagious than even Erich von Stroheim’s 1925 silent film Greed, the Huston movie is amazingly undated and especially pertinent in our time, the last decades of the twentieth century and, now, well into the twenty-first, possibly the supreme age of greed, with no signs of abating.

Such a great film – and a good review, too. I enjoyed all the background info you provided on John Huston.

Excellent review about an amazing movie, especially the background about Huston and the making of the film. Definitely one of Bogart’s best performances, and he deserves credit for playing such a paranoid, unredeemable character at the height of his career.

Great write up of a great film. I watched this just the other night on TCM.

Two comments:

1. I love Alfonso Bedoya’s accent as Gold Hat. It has a certain sing-song quality and a certain partronizing way…like he’s pretending to be nice, but has wickedness in his heart. A marvelous performance.

2. Such a well-setup scene when Dobbs is drinking from the pond and you see the reflection of Gold Hat appear in the water. Just a great way to introduce fear into the scene.

Thanks for the write up, friend!

I like the historical background information in your article.

I wrote an essay on Treasure of the Sierra Madre. While greed is certainly an important theme in the film, I focused on the paranoia of Dobbs.

A thoroughly entertaining and thought provoking movie that defies dating. The cast is absolutely superb as is the exterior photography and location. This is one film i can watch time and time again without tiring of it. A travesty of justice that it never won an Oscar for best picture. One of my all time favourite movies.

An absolute American classic and a gift to the world. Grimy is the truth. Great is also true. It lost to Olivier and Hamlet??? What were the Academy thinking that year? Is as close to the perfect film as I ever expect to see. Viva Mexico and viva gringos.