“If you’re not committed to anything, you’re just taking up space.”— Gregory Peck to Kevin McCarthy in the climax of Mirage

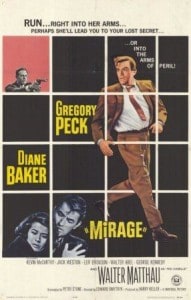

Should a latecomer arrive after the main title credits of Mirage, he might easily think he is watching a Hitchcock suspenser, the film is that good in doing what it sets out to do. The main theme of the movie, amnesia, is what haunts the same actor, Gregory Peck, in Hitch’s Spellbound. Walter Abel’s fall from a high office building recalls Norman Lloyd’s plunge from the Statue of Liberty in Hitch’s Saboteur, and any number of the director’s films, either fatal falls or otherwise—in Blackmail, Shadow of a Doubt, Rear Window, Vertigo, North by Northwest and many others.

Peck as the innocent man-on-the-run is, in fact, Hitch’s most recurring theme—in The 39 Steps, Saboteur, Shadow of a Doubt (not so innocent here!), Strangers on a Train, The Man Who Knew Too Much (both versions) and epitomized in North by Northwest. Diane Baker, the desirable, enigmatic woman who haunts Peck’s every step, though not here the director’s preferred blond, evokes any number of Hitch actresses and their wiles on screen. Baker, never quite convincing as a femme fatale, here suggests a cross between a concerned sister and an instructor, frightened herself, on how Peck can stay alive.

Certainly stairs occur in Mirage, though only secondarily, conceivably a metaphor for a loss of sanity—well, memory, anyway. Hitch’s staircases—in Rebecca, Saboteur, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, The Paradine Case, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Psycho and so many others—represent a character’s confusion, malice, vulnerability, almost always a change in fortune.

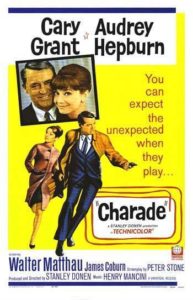

There are two strong, more specific similarities in Mirage with another, if not a Hitchcock film, then a Hitch-like one, Charade, directed by Stanley Donen a few years before Mirage. In Mirage, a man is bludgeoned with the butt of a pistol and tossed in a bathtub; the counterpart in Charade, where George Kennedy, also another nasty character in Mirage, is drowned in one. In another parallel, a detective in Mirage and a phony CIA man in Charade both occupy an office “while the secretary is out to lunch.” The actor in both cases is Walter Matthau.

There are two strong, more specific similarities in Mirage with another, if not a Hitchcock film, then a Hitch-like one, Charade, directed by Stanley Donen a few years before Mirage. In Mirage, a man is bludgeoned with the butt of a pistol and tossed in a bathtub; the counterpart in Charade, where George Kennedy, also another nasty character in Mirage, is drowned in one. In another parallel, a detective in Mirage and a phony CIA man in Charade both occupy an office “while the secretary is out to lunch.” The actor in both cases is Walter Matthau.

These similarities shouldn’t be surprising. Peter Stone, who scripted Charade, also wrote the screenplay for Mirage, based on the novel by Howard Fast, pseudonym in the credits for Walter Ericson. Mirage is directed by veteran Edward Dmytryk, a director of such diverse films as Hitler’s Children, Murder, My Sweet, The Caine Mutiny and Raintree County.

Despite an absence of the requisite shadowy lighting and a less than dark score by Quincy Jones, Mirage could, in one strong aspect, pass for a film noir. Peck is certainly in a “noir” situation, that is, his life is at stake, and he is pursued by numerous unsavory characters. A whole gang, in fact, is out to get him. Exactly why he is a target is the key to the film’s suspense, and considerable suspense there is. And related to this, what Hitchcock would call the “MacGuffin,” what is it that everybody is after? Further connected, what is it Peck can’t remember? He doesn’t know, he says. Or does he? . . .

Despite an absence of the requisite shadowy lighting and a less than dark score by Quincy Jones, Mirage could, in one strong aspect, pass for a film noir. Peck is certainly in a “noir” situation, that is, his life is at stake, and he is pursued by numerous unsavory characters. A whole gang, in fact, is out to get him. Exactly why he is a target is the key to the film’s suspense, and considerable suspense there is. And related to this, what Hitchcock would call the “MacGuffin,” what is it that everybody is after? Further connected, what is it Peck can’t remember? He doesn’t know, he says. Or does he? . . .

And if the people after him are the cause of his dilemma, just as many others are unsympathetic to his plight—a bartender, a doorman, a desk sergeant and, most insensitive, a psychiatrist. Even this woman, played by Baker, seems basically indifferent and, yes, that word again, “shady.” She is the unknown factor in it all. She seems to be on both sides, for and against the man she seems to be following.

But the audience might change its mind about Baker when another quality emerges during a little girl’s (Eileen Baral) tea party. Only the drink is coffee, the “coffee” poured from an empty pot by the child who is home alone, re-enacting a grownup’s life. Baker’s character reveals a tender interaction with the little girl—a sign she would make a good wife?—and when Peck reaches in his pocket to shell out a tip, she suggests that a simple “thank you” is all that is necessary.

And after giving up trying to explain to an insensitive policeman and an arrogant psychiatrist that someone is trying to kill him, the one stranger who becomes a friend, a laid-back private detective he hires, ends up murdered, making Peck as much alone as he was at the start of his nightmare.

But to begin . . . at the beginning, here is a highly condensed synopsis:

Mirage opens in the dark, on the twenty-seventh floor of an office tower in New York City. The first Hitchcock film that comes to mind that so opens is Suspicion, Cary Grant and Joan Fontaine’s train coming out of a tunnel. David Stillwell (Peck), a cost accountant, or so he says, meets Shela (Baker) in a stairwell during a power outage. That she remembers him and he not her, that she speaks of an unknown “Major,” are the first clues that something is amiss with his memory, possibly his mind.

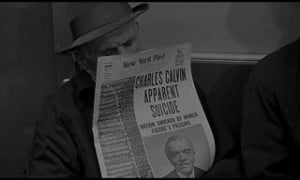

Leaving the building, he walks past a man, dead on the sidewalk, who has fallen from one of the high office windows, and on a subway ride he reads the headline on a commuter’s newspaper that the victim was Charles Calvin (Abel), a famous humanitarian. (My, that news was reported, printed and distributed almost instantaneously, even for a time when late editions were common!)

Leaving the building, he walks past a man, dead on the sidewalk, who has fallen from one of the high office windows, and on a subway ride he reads the headline on a commuter’s newspaper that the victim was Charles Calvin (Abel), a famous humanitarian. (My, that news was reported, printed and distributed almost instantaneously, even for a time when late editions were common!)

At his apartment, Stillwell is confronted by a congenial, talkative man with a gun, Lester (Jack Weston), who says “the Major” wants to see him. Stillwell subdues the intruder, but, alarmingly, finds that his refrigerator and briefcase are empty. He receives a phone call from Josephson (Kevin McCarthy), referring to some trip to Barbados; moments before, Stillwell had tried unsuccessfully to call Josephson, using an area code that had been changed two years ago.

Fearful for his life, Stillwell consults a desk sergeant (Hari Rhodes) who trivializes the idea that someone is trying to kill him. “Forget it!” Stillwell says. Next, from a skeptical psychiatrist (Robert H. Harris) he learns that the two-year memory loss he describes, which suggests unconscious amnesia, can last no more than two days, at the most. “To hell with you, doctor!”

Fearful for his life, Stillwell consults a desk sergeant (Hari Rhodes) who trivializes the idea that someone is trying to kill him. “Forget it!” Stillwell says. Next, from a skeptical psychiatrist (Robert H. Harris) he learns that the two-year memory loss he describes, which suggests unconscious amnesia, can last no more than two days, at the most. “To hell with you, doctor!”

Stillwell next resorts to a private detective, Ted Caselle (Matthau). Turns out, he has no secretary (the one “out to lunch”), no partner and this is his first case. “Terrific!” Caselle suggests they retrace his client’s steps. At Stillwell’s apartment, the refrigerator is now stuffed with food, the briefcase full of papers and Lester’s hat and gun Stillwell had put in the closet—gone.

The entry door to his supposed office, Garrison Limited, is now a solid wall. And descending to the lowest level of the building, the two men find that the subbasements Stillwell had seen before have vanished. While there, they are attacked by, but are able to subdue, a “maintenance man” (Kennedy as Willard). In the lobby, Stillwell discovers that doorman Joe Turtle (Neil Fitzgerald) is now someone else.

In a lead provided by Shela, who turns up frequently in Stillwell’s nightmare, he discovers Turtle in his apartment all right—in the bathtub, his head bashed in. And returning to Caselle’s office, Stillwell finds the detective strangled with the telephone cord.

In the film’s climax, this helpless and bewildered man-on-the-run confronts his adversaries—Josephson, Willard and the seemingly fence-straddling Shela (Lester has been killed by Willard). He meets, finally, “the Major,” actual name Crawford (Leif Erickson), a retired Army officer and Calvin’s deputy.

In the film’s climax, this helpless and bewildered man-on-the-run confronts his adversaries—Josephson, Willard and the seemingly fence-straddling Shela (Lester has been killed by Willard). He meets, finally, “the Major,” actual name Crawford (Leif Erickson), a retired Army officer and Calvin’s deputy.

Having reclaimed bits of memory earlier, Stillwell now fits together the final pieces of his identify and past, even as Willard is slugging him. He is not a cost accountant, but a physical chemist, and what Crawford has been after is his formula for neutralizing atomic bomb radiation, to make a “safe” bomb. And Calvin’s death? Stillwell was burning the only existing copy of the formula when Calvin grabbed for it and fell out the window. (Speaking of movie similarities, Abel’s earlier speech about the “little ants” below on the pavement recalls Orson Welles’ to Joseph Cotton on the Ferris wheel in Citizen Kane.) Calvin’s fall, then, generated Stillwell’s amnesia—and his subsequent guilt that he was responsible for the death.

In a game of Russian roulette, Crawford tries to persuade Stillwell to write down the formula. So far, so good: the first two “clicks” are impotent, but the game is interrupted by a fight. When Josephson inadvertently retrieves the dropped gun, Stillwell reminds him that he, now, has the power, control of the situation. “If you’re not committed to anything,” Stillwell says, “you’re just taking up space,” and convinces him to call the police. Stillwell and Shela embrace on the balcony as the police work in the background. Fade out.

For the sake of economy in that synopsis, many of the examples of Stillwell’s amnesia were deleted, as were some of the encounters with his adversaries, including a chase through New York City’s Central Park. Removed, too, were at least two love scenes and that tender interlude of the “tea” party referred to earlier, all which some will see as unnecessary digressions from the mystery. That long scene of dénouement with “the Major” is a bit protracted, however well crafted the suspense and the cascading revelations.

For the sake of economy in that synopsis, many of the examples of Stillwell’s amnesia were deleted, as were some of the encounters with his adversaries, including a chase through New York City’s Central Park. Removed, too, were at least two love scenes and that tender interlude of the “tea” party referred to earlier, all which some will see as unnecessary digressions from the mystery. That long scene of dénouement with “the Major” is a bit protracted, however well crafted the suspense and the cascading revelations.

The plot of Mirage is complicated, and for most of the time the audience may be as confused as Stillwell. Maybe that’s the intent of the film, for viewer and actor, both, to discover what’s happening. In any case, Mirage should be seen several times to be fully appreciated.

The numerous memory flashbacks—two men under a tree, a man falling, memory-jogging lines from previous scenes—must have been a nightmare in a different way for film editor Ted J. Kent—The Bride of Frankenstein, My Man Godfrey (1936), The Wolf Man. Cinematography is by Joseph MacDonald, whose own credits include My Darling Clementine, The Young Lions, The Sand Pebbles and The List of Adrian Messenger, a sentimental favorite of this writer.

For Quincy Jones, who had scored The Pawnbroker the year before, the music is only sometimes noticeable, the perfect illustration, for those who believe such, that a good score is an unnoticed score. Even when the music is forward enough to become a true part of the movie, it is not always suspense-appropriate or otherwise effective. Jones would also score the weak, even more confusing remake of Mirage in 1968. In Jigsaw, with Bradford Dillman in the Peck role, the score does little to help the already script-muddled film.

Finally—and a welcomed contrast to what is, after all, a very dark film—the exchanges between Peck and Matthau are the best, most humorous parts of the film. Simply put, Matthau steals the show, hands down. The most sprightly repartee occurs during Caselle’s first visit to Stillwell’s apartment, illustrated in this excerpt from their dialogue, beginning with the detective:

“I’ll tell you one thing, it’s kind of scary.”

“You don’t even talk like a detective.”

“ . . . What if someone wants you playing this thing all alone, without any help? What if I’m supposed to write you off as a nut and walk away?”

“What if I am a nut?”

“I don’t think you’re nuts enough to imagine that big fellow that’s been following us since we left the bank.”

“I didn’t see any one.”

“You’re not being paid to.”

“Wouldn’t it be hilarious if you did know what you’re doing?”

“Then how come I don’t know what to do next?”

“Pretend you’re James Bond. He always knows what to do.”

Ha ha – I love this line: “Pretend you’re James Bond. He always knows what to do.”

Another movie I’ve never even heard of. Yeesh! It’s a good thing I follow your blog.

Great review! …I love this film in all its strangeness, and have seen it at least a dozen times. It’s a wonderfully-atmospheric time capsule of 60’s NYC, with tremendous acting, script & cinematography. One point of disagreement …I think Quincy Jones score is eerily on-target, and really helps add to the suspense. But thanks for your deep dive into this mystery, including all the Hitchcock allusions & similar plot points. Now I’ve gotta go back & watch this again 😉

I found Mirage compelling most of the way through … before coming undone by an unsatisfying conclusion and a plot that withers under even casual scrutiny.

One is asked to believe that not only does Gregory Peck succumb to amnesia the moment he sees his boss plunging 27 stories to his death from a skyscraper window, but that all the villains somehow KNOW he has succumbed to it, and decide to play games with him based on this fact. (Why??!!)

So it’s the behavior of the bad guys that makes the least sense here.

George Kennedy sees Peck in the basement and decides to pretend he is a total stranger and send him on his way. (Why??!!)

Diane Baker runs into Peck in the stairwell and for reasons that defy understanding, decides to flee from him and answer none of his questions. (Why??!!)

Peck and Baker have several more scenes together, and even when she appears to soften and asks him to love her, she provides no illumination to the mystery — zero — even though she could, easily, at a moment’s notice. But she chooses not to. (Why??!!)

Either of these two characters, and several others besides, could have cleared up the mystery for Peck in 2 1/2 minutes … but they chose not to. Simply because it served the plot. Simply because Peck had to be in a fog for the entire running time.

The movie plays out as if the villains somehow INDUCED Peck’s amnesia in order to get him to do what they wanted, but at the end we find out this is not the case.

Am I missing something? Does the movie ever explain, A, how the villains know Peck is suffering from amnesia (seemingly from the instant he acquires it) and, more importantly, B, why they would choose to exploit this fact? How in the world does Peck’s inability to remember anything help the villains get what they want from him?

This is one of my favorite films and I have seen it more times than I can count. I feel I am qualified to answer your questions.

1. George Kennedy does not know Peck’s character yet. The Major sent him down to the basement to shut off the electricity and wait until he tells him (battery powered internal intercom line) to turn it back on.

2. When Diane Baker sees Peck in the stairwell, she is not even aware that he is in town to see Charles. She doesn’t know that Charles is dead or that the Major wants the formula

3. Diane Baker does not want to tell Peck the whole truth, because, when he learns the truth, the Major will have to kill him.

4. The Major wanted to keep Peck in the building and get his formula. Peck got out. The Major sent his men (and woman) to find him and send him to Barbados so they could torture it out of him. They were not aware of his amnesia yet. Perhaps Lester reported that Stillwell was confused and didn’t know anything.

Where were the scenes of Peck and Calvin under the tree at “the lab” filmed. Guessing it was in So Calif somewhere. Anyone know. Great photography.

THERE ARE SO MANY TWISTS . TO THING YOU CAN WATCH THIS MOVIE JUST 10 TIMES AND DIGEST THE WHOLE STORY , YOU BETTER TRY AT LEST 10 MORE AND GET OUT YOUR PEN AND PAPER . ONE OF THE BEST THRILLERS EVER . ANY ONE NOTICE THE LITTLE BIT OF J. F. K. running through it , since this was made right after J.F.K. WAS SHOT . NO BELL?