“You know, they’re only two kinds of animals that make war on their own kind—rats and men, and men are supposed to be able to think.” — Police sergeant Ferguson to forensic expert “Doc”

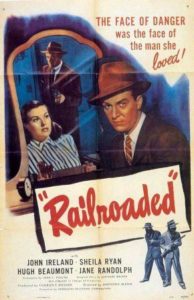

Got a few hours to spare, seventy or so minutes, to be precise? Watching Railroaded!, best appreciated the first time, will prove an excellent window into what was to come—the careers of two individuals in particular. Director Anthony Mann had already made a tentative noise in film noir with such films as Strangers in the Night and The Great Flamarion. He perhaps would have hit his stride in the genre with He Walked by Night, except he directed only part of the film, and Alfred L.Werker, who did most of the work, received screen credit. In a rather different direction, Mann’s greatest fame began in 1950 with Winchester’73, the first of a half dozen Western collaborations with James Stewart that proved the versatility of both men.

John Ireland, who had top billing in Railroaded!, made, as his future would prove, a deceptively positive impression in his first picture, A Walk in the Sun. His role as a sympathetic, intelligent GI would not be the typical role he would most often play, that of the heavy. His career in Hollywood would peak rather early—most famously in Howard Hawk’s Red River (1948) and a year later in All the King’s Men, for which he received his only Oscar nomination. His defining role in Railroaded! as a hard, almost charming killer would be one of his best.

He entered television as early as 1950, and, more and more, his career was so concentrated, with guest appearances in most of the current series, especially Westerns—Bonanza, Gunsmoke, Zane Grey Theater, Rawhide and Branded.

Railroaded! Not every movie title includes an exclamation point. Personally, the musical Oklahoma! comes immediately to mind, but there are other such titles, losers like Berserk!, the Joan Crawford gore fest, and Die, Monster, Die!, Boris Karloff as a recluse who acquires power from a meteor; another musical, Oliver!; and the dark I Want to Live!, Susan Hayward’s harrowing date with the gas chamber.

Railroaded! Not every movie title includes an exclamation point. Personally, the musical Oklahoma! comes immediately to mind, but there are other such titles, losers like Berserk!, the Joan Crawford gore fest, and Die, Monster, Die!, Boris Karloff as a recluse who acquires power from a meteor; another musical, Oliver!; and the dark I Want to Live!, Susan Hayward’s harrowing date with the gas chamber.

The product of the small Producers Releasing Corporation, Railroaded! is a sure-enough low-budget film as to the money invested and the brief filming schedule, but thanks to generally good acting, the tight script by John C. Higgins, the art direction of Perry Smith and the cinematography of Guy Roe, what’s up on the screen can almost pass for a Warner Brothers or RKO production.

In the manner of a Michael Curtiz trademark, Roe likes to photograph different perspectives with objects in the foreground. When what would now be called the forensic expert (the uncredited “criminologist,” Mack Williams) confides evidence to the police sergeant (Hugh Beaumont), the two men stand behind various objections, brightly lit in an otherwise dark room, much as another lamp is forward on a desk in the killing of the nightclub owner (Roy Gordon). In the opening scene in the beauty parlor, there are four shop hair dryers which take forward prominence, almost like characters in the drama.

In the manner of a Michael Curtiz trademark, Roe likes to photograph different perspectives with objects in the foreground. When what would now be called the forensic expert (the uncredited “criminologist,” Mack Williams) confides evidence to the police sergeant (Hugh Beaumont), the two men stand behind various objections, brightly lit in an otherwise dark room, much as another lamp is forward on a desk in the killing of the nightclub owner (Roy Gordon). In the opening scene in the beauty parlor, there are four shop hair dryers which take forward prominence, almost like characters in the drama.

Roe’s camera is equally effective when it is panning, dollying or zooming, yet when stationary and the actors move both in the foreground and in the background, the screen holds interest.

The main title sets the mood rather well, if typical in this genre, with a night scene of the Big City, a wide, lighted street disappearing into the distance. Black and white, of course. The musical score, which here already includes a piano, is by Alvin Levin, whose work was confined to five films in 1947, of which Railroaded! is the best known. At one point, when the requisite femme fatale slinks back to her apartment after making a phone call to the police—information in exchange for protection—the music is appropriately creepy and mysterious; at other times, Levin is too intrusive, more dramatic or emphatic than certain scenes require. For the most part, the score seems a timid participant in things, though the film is strongly sufficient on its own.

A slight digression . . . How many noir films begin with a night view of a city? Too many to count. For one, there is Don’t Bother to Knock, mentioned here only because it was recently seen for the first time, concurrent with this writing. It was made in 1952, with Richard Widmark, Marilyn Monroe, Elisha Cook, Jr. and Anne Bancroft in her film début. The score behind this main title, also a night view of a city, is apparently the product of a committee, with Lionel Newman as “music director” and help from Earle Hagen, Bernard Mayers and, most notably, an uncredited Jerry Goldsmith, who did some orchestrating. Point is, the main title music here is far more exciting and anticipatory than Levin’s in Railroaded!, though neither score delivers what it promises in the main title.

After some traveling music, the camera moves directly from the main title to the store front of a hairdresser’s shop, Clara Calhoun, The House of Beauty. Behind the establishment, where business is slow—Clara (Jane Randolph) is impatiently seeing out her last customer—we find a bookie joint in the back room. Marie (Peggy Conserve) is another hairdresser.

After some traveling music, the camera moves directly from the main title to the store front of a hairdresser’s shop, Clara Calhoun, The House of Beauty. Behind the establishment, where business is slow—Clara (Jane Randolph) is impatiently seeing out her last customer—we find a bookie joint in the back room. Marie (Peggy Conserve) is another hairdresser.

Clara opens and closes the back door several times, a signal for two men with shotguns waiting in the alley. One man (Ireland) takes the money, but not before he has killed a policeman and his henchman Kowalski (Keefe Brasselle) is severely wounded.

A U.S. Navy scarf stenciled “S.R.R.” was apparently left by one of the intruders. This leads to sailor Steve Ryan (Ed Kelly), who has been unfavorably associated with Kowalski and is an automatic suspect. Sergeant Mickey Ferguson (Beaumont) interrogates Steve, who has a flimsy alibi, and meets his sister Rosie (Sheila Ryan, who married Pat Buttram and died at fifty-four). Charles D. Brown, an unheralded but familiar face in so many films, is effective as cautious but determined Police Captain MacTaggart. He almost makes a stronger impression than Beaumont.

A U.S. Navy scarf stenciled “S.R.R.” was apparently left by one of the intruders. This leads to sailor Steve Ryan (Ed Kelly), who has been unfavorably associated with Kowalski and is an automatic suspect. Sergeant Mickey Ferguson (Beaumont) interrogates Steve, who has a flimsy alibi, and meets his sister Rosie (Sheila Ryan, who married Pat Buttram and died at fifty-four). Charles D. Brown, an unheralded but familiar face in so many films, is effective as cautious but determined Police Captain MacTaggart. He almost makes a stronger impression than Beaumont.

Interestingly, playing one of the policemen is a Barton MacLane look alike, Clancy Cooper, who seems to have some kind of bland charisma, though that may be a contradiction in terms. In his introduction, he stands statically between two actors, wearing a hat, as men did in the ’40s, his head tilted slightly down. He continually chews gum, his eyes shifting back and forth, almost as if he should have been cast as a criminal. When he speaks, and he speaks blandly, it’s only a word or two. He has little to do in the remainder of the film, and yet he somehow has a fascinating presence.

The plot unfolding, Ireland is the gangster Duke Martin, manager of the Club Bombay and its outside gambling connections. The club is owned by Ainsworth (Gordon), who is forever quoting the famous, once attributing “Women should be struck regularly—like gongs,” to Oscar Wilde, a line actually from Noel Coward. One quote, uncredited, belongs to American writer Ambrose Bierce: “You are not permitted to kill a woman who has wronged you, but nothing forbids you to reflect that she is growing older every minute.” Wilde did say, however, “One should never trust a woman who tells one her real age. A woman who would tell one that, would tell one anything.”

Martin is the lover and babysitter for his alcoholic moll Clara, hole up in an apartment until Steve’s trial. She was obviously in with Martin on the beauty shop robbery. Marie, because she knows too much, is found in the river. Rosie, on a visit on behalf of her brother, has a full-fledged, knock-down-drag-out fight with Clara—hair-pulling, falling over furniture, knocking over lamps—while a hiding Martin watches from the shadows.

Martin is the lover and babysitter for his alcoholic moll Clara, hole up in an apartment until Steve’s trial. She was obviously in with Martin on the beauty shop robbery. Marie, because she knows too much, is found in the river. Rosie, on a visit on behalf of her brother, has a full-fledged, knock-down-drag-out fight with Clara—hair-pulling, falling over furniture, knocking over lamps—while a hiding Martin watches from the shadows.

Martin has all kinds of sexual fetishes, perfuming his bullets and rubbing his handkerchief over his cigarette case and revolver. From the dead policeman, “Doc” shows Ferguson the perfumed bullet that is one of the links to Martin. Sex and hand guns were the point of a scene in Red River in which Ireland and Montgomery Clift compare the size of their guns, presumably comparing something else!

As the relationship between Martin and Clara deteriorates—he eventually kills her when he discovers she has squealed on him—that between Rosie and Ferguson strengthens, despite the strong impression Martin makes on her at one point. Her susceptibility to Duke’s influence, knowing his criminal connections, is a digression that somehow rings false. Even her response to Ferguson seems tepid at best. A quick kiss on her doorstep is matter-of-fact, and, before and after, they talk as if nothing had happened. The love interests, perhaps, were not of particular interest to director Mann.

The climax of Railroaded! comes in the dark of the Club Bombay, a grand shootout, Western style. Ferguson crashes through the glass door with a garbage can as a shield, and the gunfire continues from behind overturned tables. Martin has cornered Rosie and delivers that familiar, trite line: “Nobody makes a sucker out of me.” His shooting her seems visibly fatal—she’s about to pass out—but afterward, in the final embrace with Ferguson, her arm in a sling indicates a superficial wound. Duke Martin, of course, ends up dead.

The climax of Railroaded! comes in the dark of the Club Bombay, a grand shootout, Western style. Ferguson crashes through the glass door with a garbage can as a shield, and the gunfire continues from behind overturned tables. Martin has cornered Rosie and delivers that familiar, trite line: “Nobody makes a sucker out of me.” His shooting her seems visibly fatal—she’s about to pass out—but afterward, in the final embrace with Ferguson, her arm in a sling indicates a superficial wound. Duke Martin, of course, ends up dead.

Hugh Beaumont (Police Sgt. Mickey Furguson) also hit it big. He played Ward Cleaver on ‘Leave it To Beaver’. Child psychology and child rearing lessons via a pretty darn entertaining, albeit mamby-pamby television show.