“If all these people are not implicated in the crime, then why have they all told me, under interrogation, stupid and often unnecessary lies? Why? Why? Why? Why?”——Hercule Poirot

It’s a long journey by rail from Istanbul to Calais. Even on so luxurious a train as the Orient Express in its glory days of the 1930s. In one such film odyssey, all the passengers make it, not all the way to Calais, “with connections to London,” as announced in the station at the start of the journey, but only to Yugoslavia. All passengers make it through the movie, that is, except one. One is murdered. In a way, murdered twelve times. Twelve stab wounds.

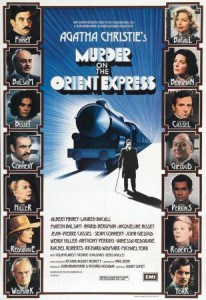

The 1974 Murder on the Orient Express inspired a series of star-studded Agatha Christie films and TV movies. Death on the Nile was the first to follow, in 1978, then came, almost in descending order of quality and production value, at least five more mysteries, including Evil Under the Sun starring [intlink id=”135″ type=”category”]Peter Ustinov[/intlink] and A Caribbean Mystery with Helen Hayes.

The most recent remakes of Orient Express have been two TV movies. The one in 2001 starring Alfred Molina as detective Hercule Poirot is a pale shadow of the ’74 original—almost as expected, the usual “unnecessary” rule regarding remakes in effect here. Considering the usual quality of that BBC/PBS Masterpiece Mystery TV series with David Suchet as the Belgium sleuth, in 2010 came a surprisingly weak version, replete with plot-confusing omissions and shoddy sets, with Suchet merely going through the motions, as if rushed by some budget constraint.

Not that the’74 version of Murder on the Orient Express is without its flaws. True, it has much going for it: resplendent ’30s atmosphere and décor, elaborate period attire, that stellar cast already mentioned, fine ensemble acting by all involved and an elaborate, Oscar-nominated score by Richard Rodney Bennett. Especially according to audience’s need today for glitzy action, superficial character development and little exposition, the film’s major flaw is that it is terribly “British” in its slow, methodical pace, criticized even when the movie first appeared forty years ago.

Not that the’74 version of Murder on the Orient Express is without its flaws. True, it has much going for it: resplendent ’30s atmosphere and décor, elaborate period attire, that stellar cast already mentioned, fine ensemble acting by all involved and an elaborate, Oscar-nominated score by Richard Rodney Bennett. Especially according to audience’s need today for glitzy action, superficial character development and little exposition, the film’s major flaw is that it is terribly “British” in its slow, methodical pace, criticized even when the movie first appeared forty years ago.

The Christie plot is simplicity itself. Like most of her mysteries, there is a murder (sometimes a second or third) and a room full of at least ten suspects—or ship full, or archaeological camp full, or, yes, train full of suspects. Poirot (Albert Finney), then, is left to do his work, with, strangely, no sense of urgency, no awareness of the possibility that other murders might occur.

Following the exuberant, 1930-ish period main title comes a kaleidoscopic montage of distorted scenes, blurred images and newspaper headlines from 1930, recounting the kidnapping and murder of little Daisy Armstrong. The apparent participants include a governess, a military colonel, a maid, a chauffeur, a policeman on his beat, a number of others. (Not coincidentally, Christie’s novel appeared two years after the famous kidnapping and murder, in 1932, of Charles Lindbergh’s twenty-month-old son.)

The film now segues to 1935. The Orient Express has left Istanbul, headed on its northwesterly journey. The first night, en route to Paris, one passenger in the Calais coach, “businessman” Monsieur Ratchett ([intlink id=”155″ type=”category”]Richard Widmark[/intlink]), is found murdered in his compartment bed—stabbed twelve times. Some of the wounds are deep, some rather shallow, others “hardly more than scratches.” Shortly before, Ratchett had asked Poirot to take his case, that he had been receiving threatening letters and sleeping with a gun under his pillow. Interestingly, in the only scene between the two men, viewers learn the proper pronunciation of the detective’s name, not Per-row as Ratchett persists in addressing him, even after corrected, but Pauw-row.

The film now segues to 1935. The Orient Express has left Istanbul, headed on its northwesterly journey. The first night, en route to Paris, one passenger in the Calais coach, “businessman” Monsieur Ratchett ([intlink id=”155″ type=”category”]Richard Widmark[/intlink]), is found murdered in his compartment bed—stabbed twelve times. Some of the wounds are deep, some rather shallow, others “hardly more than scratches.” Shortly before, Ratchett had asked Poirot to take his case, that he had been receiving threatening letters and sleeping with a gun under his pillow. Interestingly, in the only scene between the two men, viewers learn the proper pronunciation of the detective’s name, not Per-row as Ratchett persists in addressing him, even after corrected, but Pauw-row.

As eccentric as another Christie sleuth, Miss Jane Marple, is down-to-earth, Poirot has an abundance of clues. He even remarks over Ratchett’s glassy-eyed body in a sing-song voice, “There are too many clu-u-u-ues in this ro-o-o-om.” Inside and outside the room, the clues include two different pipe cleaners in the ashtray, which also contains a half-smoked cigar; a handkerchief with the letter “H”; a burnt piece of paper; a smashed watch; the drugging of Ratchett’s nightly sleeping potion; the sight of a person in a white kimono disappearing down a passageway; a lost button from a train conductor’s uniform; and a cry, as during a nightmare, from the victim during the night.

As eccentric as another Christie sleuth, Miss Jane Marple, is down-to-earth, Poirot has an abundance of clues. He even remarks over Ratchett’s glassy-eyed body in a sing-song voice, “There are too many clu-u-u-ues in this ro-o-o-om.” Inside and outside the room, the clues include two different pipe cleaners in the ashtray, which also contains a half-smoked cigar; a handkerchief with the letter “H”; a burnt piece of paper; a smashed watch; the drugging of Ratchett’s nightly sleeping potion; the sight of a person in a white kimono disappearing down a passageway; a lost button from a train conductor’s uniform; and a cry, as during a nightmare, from the victim during the night.

From interviews with the twelve occupants of the Calais coach, the detective must gather the last bits of information and glean further clues.

The suspects vary in nationality, social class and disposition. First, Ratchett’s nervous secretary Hector McQueen (Anthony Perkins) and the dead man’s valet Beddoes (John Gielgud); the only suspect name changed from the novel. The American loudmouth Mrs. Hubbard (Lauren Bacall) from whom all others flee: “Mrs. Hubbard is upon us,” cries one of the passengers. The contrite Swedish custodian of “little brown babies” Greta Ohlsson ([intlink id=”187″ type=”category”]Ingrid Bergman[/intlink]).

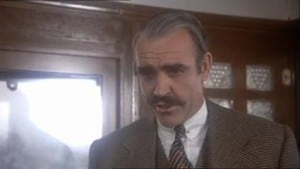

The Count and Countess Andrenyi (Michael York and Jacqueline Bisset), whose passport has a strange, seemingly convenient stain masking a crucial letter. The Scot, Colonel Arbuthnot ([intlink id=”213″ type=”category”]Sean Connery[/intlink]), who believes that a “trial by twelve good men and true is a sound system,” and the lover Mary Debenham (Vanessa Redgrave) he intends to marry when his divorce is final. “Miss Debenham,” he says, “is not a woman. She is a lady.”

The Count and Countess Andrenyi (Michael York and Jacqueline Bisset), whose passport has a strange, seemingly convenient stain masking a crucial letter. The Scot, Colonel Arbuthnot ([intlink id=”213″ type=”category”]Sean Connery[/intlink]), who believes that a “trial by twelve good men and true is a sound system,” and the lover Mary Debenham (Vanessa Redgrave) he intends to marry when his divorce is final. “Miss Debenham,” he says, “is not a woman. She is a lady.”

Also interviewed, the Russian princess Dragomiroff (Wendy Hiller) and her German maid (Rachel Roberts), who reads Goethe to her frail, always black-attired mistress. The train conductor Pierre Michel (Jean-Pierre Cassel), who inexplicably knows the names of many of the passengers before he receives their tickets. The Italian auto salesman Antonio Foscarelli (Denis Quilley): “American cars to Italians.” And, interviewed last, almost as a script afterthought, the Pinkerton detective Hardman (Colin Blakely, who played Dr. Watson to Robert Stephens’ Sherlock Holmes in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes).

Also starring, although never suspects, are Martin Balsam as director of the rail line, George Coulouris as the doctor onboad and Vernon Dobtcheff, briefly seen as the concierge before the train’s departure. Followers of the the Poirot Masterpiece Mystery installments might recall Dobtcheff as the evil Simeon Lee in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, sometimes known under the alternative title Murder for Christmas, one of the best installments of that TV series of one of Christie’s more obscure mysteries, from 1938.

The Orient Express is blocked by a snowdrift, and a disproportionate amount of screen time is given to the status of the anticipated work crew or snowplow, almost to the point of viewer fatigue. Perhaps the frequent emphasis is to heighten excitement, as Poirot must decide on a solution before help arrives, along with the Yugoslavian police.

The Orient Express is blocked by a snowdrift, and a disproportionate amount of screen time is given to the status of the anticipated work crew or snowplow, almost to the point of viewer fatigue. Perhaps the frequent emphasis is to heighten excitement, as Poirot must decide on a solution before help arrives, along with the Yugoslavian police.

There is, of course, the simple explanation for the murder, the one the real murders—yes, there are more than one!—have clumsily improvised, since they didn’t anticipate Poirot being on the train. The ploy of the planted lost trainman’s button ties to the assumption that the lone murderer escaped while the train was stalled in the snowdrift.

Contrary to the detective’s edict that he always brings the guilty to justice, this is the version of the murder he will tell the police, not the real one which Poirot explains in the long, long dénouement, accompanied by linking references to the opening montage, a dénouement that occupies more than half the film. The motive for the murder, of course, is revenge for Ratchett’s involvement with the Daisy affair, and that all twelve passengers in the Calais coach are in some way connected with the Armstrong family.

Orient Express is a one-murder mystery in Christie’s best, succinct manner, though, as usual with the attention-loving Hercule Poirot, climaxed by an analysis of the case and the identity of the murderer or, in this case, murderers. For the detective, it is the science of it all, or, as he delights in saying, the results of using his “little gray cells.”

In Orient Express, as in most of Christie’s stories, the interest lies not so much in the method of the victim’s dispatch as in the personalities of the many suspects and the study of their characters and motivations. Not to be disparaged, the author is, however, most inspired in her choice of murder weapons, whether knives, guns, any variety of blunt instruments, hypodermic injections, nylon stockings, falls from cliffs, even an electrocution in The Big Four. But Christie’s favorite killing method is probably poison, in all its numerous concoctions. She dispensed hospital drugs during both world wars. And so it is poison that dispatches Ratchett.

In Orient Express, as in most of Christie’s stories, the interest lies not so much in the method of the victim’s dispatch as in the personalities of the many suspects and the study of their characters and motivations. Not to be disparaged, the author is, however, most inspired in her choice of murder weapons, whether knives, guns, any variety of blunt instruments, hypodermic injections, nylon stockings, falls from cliffs, even an electrocution in The Big Four. But Christie’s favorite killing method is probably poison, in all its numerous concoctions. She dispensed hospital drugs during both world wars. And so it is poison that dispatches Ratchett.

Orient Express, a detective story subsisting on only one murder, is quite contrary to the current trends, particularly on TV, where supposed police “experts” stumble through three or four murders, sometimes more, before the killer is apprehended, an ineptitude that would earn a firing in most real police departments. This bumbling appears in both the big city of Law and Order and in the tranquil British village of Midsomer Murders.

On occasions Christie was known to succumb to excess, or “over-kill,” if a good plot ploy presented itself. In Ten Little Indians, a.k.a. And Then There Were None, ten people die according to the scheme of a nursery rhyme. And the murderer of nine commits suicide, making the total ten, so there’s no need for a Christie detective—either Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple or Ariadne Oliver. Or anybody!

Hinted at earlier in reference to the bright main title, Orient Express is greatly assisted by one of Richard Rodney Bennett’s finest scores. It earned him his third Oscar nomination, though he lost to the team who scored The Godfather, Part II, Nino Rota and Carmine Coppola, director Francis Ford Coppola’s father. Bennett had been nominated in 1967 for Far from the Madding Crowd and in 1971 for Nicholas and Alexandra. A one-time student of French composer-conductor Pierre Boulez, he also scored the Cary Grant-Ingrid Bergman Indiscreet, Lady Caroline Lamb and, toward the end of his career, though with much classical source music, Three Weddings and a Funeral.

The main title of Orient Express opens with a brilliant flourish, the orchestra and a piano in an impressive introduction, rich with expectation and excitement. The musical color and flavor suggest the 1930s, aided by the art deco lettering and border and a pink satin background. The piano, solo now, then improvises, followed by scales that lead into what must be a love theme—though for whom?! The orchestra, predominately the strings, now joins the piano in an elaboration on the theme.

The main title of Orient Express opens with a brilliant flourish, the orchestra and a piano in an impressive introduction, rich with expectation and excitement. The musical color and flavor suggest the 1930s, aided by the art deco lettering and border and a pink satin background. The piano, solo now, then improvises, followed by scales that lead into what must be a love theme—though for whom?! The orchestra, predominately the strings, now joins the piano in an elaboration on the theme.

The piano is there, perhaps, because someone along the way—director Sidney Lumet, perhaps?—wanted something like the Warsaw Concerto (from Richard Addinsell’s 1941 score for Dangerous Moonlight). Who was it said directors know nothing about music? (David Raksin? He was outspoken enough!) In another secondhand idea, someone else suggested that Bennett make his score a pastiche of Gershwin tunes. He was rumored to have said that that sort of thing has been done, too much of a cliché.

There is, of course, the effective and eerie music from the montage, but the most memorable music in the score, by far, is the waltz, the traveling tune that accompanies the Orient Express on its journey. The waltz is held back until the right moment, and when it is introduced, it is done most dramatically, enough to make it, in conjunction with the screen image, one of the great moments of the movies. Geoffrey Unsworth’s camera—he was also Oscar-nominated for his cinematography—moves down the platform alongside the standing train to the front of the engine while Bennett’s score begins in a rustle of timpani rolls, quirky woodwinds and hints of the theme to come. Artful anticipation at its best! The engine, by the way, is 230-G-353.

There is, of course, the effective and eerie music from the montage, but the most memorable music in the score, by far, is the waltz, the traveling tune that accompanies the Orient Express on its journey. The waltz is held back until the right moment, and when it is introduced, it is done most dramatically, enough to make it, in conjunction with the screen image, one of the great moments of the movies. Geoffrey Unsworth’s camera—he was also Oscar-nominated for his cinematography—moves down the platform alongside the standing train to the front of the engine while Bennett’s score begins in a rustle of timpani rolls, quirky woodwinds and hints of the theme to come. Artful anticipation at its best! The engine, by the way, is 230-G-353.

Simultaneous with a giant forte chord from the orchestra, the headlight comes on (one writer mistook the sudden glare for a spotlight). Doors are closed on the carriages and the train slowly begins pulling out of the station. The waltz starts slowly, then faster and faster as the train increases speed, and a solo French horn floats a counter melody above it all. The camera swings to focus on the passing cars, the table lamps clearly visible through the windows of the dining car, then fixes on the golden, embossed Orient Express emblem on the second-to-last car, as the train passes down the track and out of the station. From the moment the train begins to move, it’s done in one unbroken shot; it is said that Unsworth had only one chance to get it right.

The waltz and the theme from the main title are combined in the film’s conclusion when the passengers of the Calais coach toast Hercule Poirot for his brilliant deduction—obviously the one they wanted! Beginning when Mary Debenham kisses Mrs. Hubbard, the organizer of the murder, a solo oboe, for seemingly the longest time, gives out a slow version of the waltz, a high moment in the score. After the last clink of wine glasses, the waltz, back in its familiar tempo, supports the rolling end credits, joined by the French horn with the love theme.

The waltz and the theme from the main title are combined in the film’s conclusion when the passengers of the Calais coach toast Hercule Poirot for his brilliant deduction—obviously the one they wanted! Beginning when Mary Debenham kisses Mrs. Hubbard, the organizer of the murder, a solo oboe, for seemingly the longest time, gives out a slow version of the waltz, a high moment in the score. After the last clink of wine glasses, the waltz, back in its familiar tempo, supports the rolling end credits, joined by the French horn with the love theme.

The train, having been freed from the snowdrift and billowing black smoke, once more gains speed and continues on its journey.

Many years ago, in High Fidelity magazine, Royal S. Brown reviewed the soundtrack album, then a Capitol LP of course: “I have heard few musical scores that sustain the mood and ambiance of their pictures as well as Bennett’s does here. . . . [E]very note on this disc reveals the exceptional skill of one of the most talented composers writing for film today.” Sadly, Bennett died in 2012.

Further nostalgia of the period is added in some source music at the beginning of the film. A little restaurant orchestra is playing “Red Sails in the Sunset,” and since this was the time of the rage for Shirley Temple movies, the added “On the Good Ship Lollipop” seems close to a period overdose.

Albert Finney, despite the heavy body makeup, an unrecognizable face and a thick French accent (sometimes hard to understand), saw his Oscar nomination for Best Actor go to Art Carney for Harry and Tonto, sans makeup or disguised voice. Ingrid Bergman was the film’s only winner, for Supporting Actress, trumping her two strongest competitors—Diane Ladd in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and Talia Shire in The Godfather, Part II. For Ingrid, an accent and dowdy appearance paid off! The film’s other nominations, for Costume Design, went to The Great Gatsby, and for Adapted Screenplay to The Godfather, Part II.

Albert Finney, despite the heavy body makeup, an unrecognizable face and a thick French accent (sometimes hard to understand), saw his Oscar nomination for Best Actor go to Art Carney for Harry and Tonto, sans makeup or disguised voice. Ingrid Bergman was the film’s only winner, for Supporting Actress, trumping her two strongest competitors—Diane Ladd in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and Talia Shire in The Godfather, Part II. For Ingrid, an accent and dowdy appearance paid off! The film’s other nominations, for Costume Design, went to The Great Gatsby, and for Adapted Screenplay to The Godfather, Part II.

Speaking of the script, besides Poirot’s keen observations, there is much humor from the detective himself—and there is this somewhat famous exchange between two men sharing the same train compartment, Foscarelli on the top bunk and Beddoes on the bottom:

Foscarelli leans over and asks, “Hey, what are you reading Mister Beddoes?”

“I am reading Love’s Captive by Mrs. Arabella Richardson.”

“Is it about sex?”

“No, it’s about 10:30, Mister Foscarelli.”

I love this version! While Suchet is my favorite Poirot, you are 100% correct in your observations of his version of “Murder on the Orient Express.” I was truly hoping that Suchet would redo the Paul Deni script which Christie and her family loved. In addition, like you I adored Lumet’s attention to detail in immersing us in the time by using popular music of the time. Ultimately, what Lumet achieved was a brilliant blending of a truly all star cast. Each shines in his/her role and that is why I love the “curtain call” at the end. Great article on a movie I love!

This film is a bit slow but what fabulous cast and sets! I need to see it again.

Beddoes’ name change from Masterman isn’t the one. Signor Bianchi, in the original novel, is a Frenchman named Bouc, and Mrs. Hubbard’s full name in the novel is Carolina Martha Hubbard, not Harriet Belinda Hubbard.

Bouc is Belgian in the novel.

*only* one…