“With Jaglom, he seemed to find a comfort zone that enabled him to show his vulnerabilities. . . . There was no topic too insignificant or esoteric for Welles to weigh in on.”—— from Peter Biskind’s introduction to the book

Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water, or, in this case, when you thought the last [intlink id=”150″ type=”category”]Orson Welles[/intlink] archival secrets had been revealed, there seems to have been, stashed away in a shoebox for thirty years, some forty tapes, recorded conversations between British author/director Henry Jaglom and that director of Citizen Kane. Welles’ thoughts—both profound and silly, urbane and vindictive, pompous and contrite, wise and ridiculous—were recorded from 1983 until October of 1985.

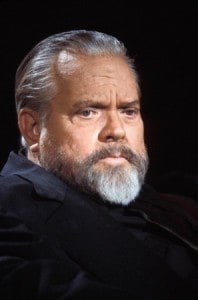

If Winston Churchill’s famous axiom about Russia should ever be applied to a person, it could suit no one more aply than the elusive complexity that was Orson Welles: “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” Even these revelations, most of them mild and not unexpected, are merely part of the flow that will continue—more deductions, conjectures and assumptions about this man. As Peter Biskind wrote in his twenty-six-page introduction, Welles was, all in one, “the brilliant child prodigy, the precedent-shattering stage director, the iconoclastic radio figure, the celebrated Shakespearean artist, the ground-breaking filmmaker credited by almost everyone with having made the greatest movie of all time . . . ”

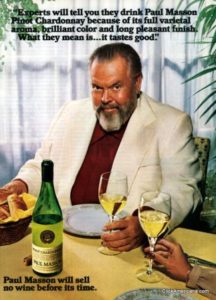

There is, on the other hand, as Biskind also points out, the quite different “TV talk show buffoon, the corny wine commercial huckster, the willing participant in tasteless low-comedy ‘roasts,’ the bloated, seemingly self-destructive outcast whose finished works and aborted projects became legendary . . . ”

There is, on the other hand, as Biskind also points out, the quite different “TV talk show buffoon, the corny wine commercial huckster, the willing participant in tasteless low-comedy ‘roasts,’ the bloated, seemingly self-destructive outcast whose finished works and aborted projects became legendary . . . ”

And it is these diametric extremes between intelligence and buffoonery that set the general tone of Welles’ conversations with Jaglom.

I remember those Dean Martin roasts—“low-comedy” indeed they were, but in a moment of critical frailty, perhaps, I enjoyed them!—and recall, too, Welles’ recurring sessions on Merv Griffin’s talk show. In fact, it was a few hours after a Griffin interview that the star died, of a heart attack. As Biskind writes, “with a typewriter on his lap, working on a script.”

After a thumbnail sketch on Welles in his introduction, Biskind relates how Jaglom met Welles and how the recordings began. In 1978, the two men were having lunch at least once a week at the actor’s favorite haunt, Ma Maison in West Hollywood, opened in 1975 by the French restaurateur Patrick Terrail. Welles agreed to the taping, only if the recorder was unseen, concealed in a bag. On occasions, because of the bag, some of the words are muffled, even inaudible. Biskind has “taken occasional liberties” to make the text more succinct and lucid. The book of conversations is generally in chronological order, but related topics are grouped together.

Ironically, Terrail would relinquish ownership of Ma Maison a month after Welles’ death.

To somewhat set the tone of the conversations to come, Biskind relates that Terrail was kind of a courier for people who wanted to contact Welles. Terrail relayed to the Big Man, which he was—the size of a baby elephant, as Biskind describes him—that George Stevens, Jr. wondered if the director would accept a Kennedy Center award, that the Center would fly him to Washington. “No,” Welles replied. “I would have to sit next to Reagan in the box up there.”

To somewhat set the tone of the conversations to come, Biskind relates that Terrail was kind of a courier for people who wanted to contact Welles. Terrail relayed to the Big Man, which he was—the size of a baby elephant, as Biskind describes him—that George Stevens, Jr. wondered if the director would accept a Kennedy Center award, that the Center would fly him to Washington. “No,” Welles replied. “I would have to sit next to Reagan in the box up there.”

Similarly, once when the archbishop of the Greek Orthodox Church came by the table and invited Welles to high mass at the Cathedral of Saint Sophia and offered to dedicate the service to him, Welles replied, “I am flattered by the invitation, but I must decline. I’m an atheist.”

Each of the twenty-seven chapters is headed with a boldfaced Wellesian quote contained in the text and, below it, a three- or four-line summary of the topics discussed. In the general order of the book, the following are a few of Orson Welles’ comments—and one of Jaglom’s that seemed humorous enough to include:

On Spencer Tracy: “Tracy hated me, but he hated everybody. Once I picked him up in London, in a bar, to take him out to Nutley Abbey [home of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh]. Everybody came up to me and asked for autographs and didn’t notice him at all. I was the Third Man, for God’s sake, and he had white hair. What did he expect? And then he sat there at the table saying, ‘Everybody looks at you, and nobody looks at me.’ All day long, he was just raging. Because he was the big movie star, you know.”

On Carole Lombard and on the plane crash that killed her: “Very bright. Brighter than any director she ever worked with. She had all the ideas. Jack Barrymore told me the same thing. He said, ‘I’ve never played with an actress so intelligent in my life.’ . . . You know why her plane went down? It was full of big-time American physicists, shot down by the Nazis. She was one of the only civilians on the plane. The plane was filled with bullet holes.” When Jaglom called the idea preposterous, Welles asserted: “The people who know it, know it. It was greatly hushed up. The official story was that [the plane] ran into the mountain.”

On David O. Selznick: “Selznick wanted to be the greatest producer in the world—and would have been happy to do anything to achieve it. It was unbelievable. Once I was on David’s yacht, and we were all gathered together after dinner. He said, ‘We can either go back to Miami tonight, or we can go to Havana. I’d like to see a show of hands. Who wants to go to Havana?’ Everybody’s hands went up. We all went to bed, woke up in Miami.”

On Norma Shearer, wife of producer Irving Thalberg: “After Thalberg died, Norma Shearer—one of the most minimally talented ladies ever to appear on the silver screen, and who looked like nothing, with one eye cross over the other—went right on being the queen of Hollywood, and getting one role after another. . . . And everybody used to say, ‘Miss Thalberg is coming,’ ‘Miss Shearer is arriving,’ and all that, as though they were talking about Sarah Bernhardt.”

On Norma Shearer, wife of producer Irving Thalberg: “After Thalberg died, Norma Shearer—one of the most minimally talented ladies ever to appear on the silver screen, and who looked like nothing, with one eye cross over the other—went right on being the queen of Hollywood, and getting one role after another. . . . And everybody used to say, ‘Miss Thalberg is coming,’ ‘Miss Shearer is arriving,’ and all that, as though they were talking about Sarah Bernhardt.”

Jaglom on his meal, to the waiter: “Uh, you gave me cold chicken. And I wanted warm chicken salad . . . The plate is very good and hot—the plate is excellent. If I were eating the plate, I would have been happy. But the chicken——”

On television and bad movies: “Other people want to switch channels. I don’t. I’d much rather see junk on the TV than bad movies because bad movies stay with me for too long. And if they get a little good, then they’re gonna haunt me. And who needs to be haunted?”

On an American drama critic: “George Jean Nathan was the tightest man who ever lived, even tighter than Charles Chaplin. And he lived for forty years in the Hotel Royalton, which is across from the Algonquin. . . . After about ten years of never getting tipped, the room-service waiter peed slightly in his tea. Everybody in New York knew it but him. The waiters hurried across the street and told the waiters at Algonquin, who were waiting to see when it would finally dawn on him what he was drinking. And as the years went by, there got to be more and more urine and less and less tea. . . . And I, with my own ears, heard him at the 21 complaining to a waiter, saying, ‘Why can’t I get tea here as good as it is at The Royalton?’ That’s when I fell on the floor, you know.”

On an American drama critic: “George Jean Nathan was the tightest man who ever lived, even tighter than Charles Chaplin. And he lived for forty years in the Hotel Royalton, which is across from the Algonquin. . . . After about ten years of never getting tipped, the room-service waiter peed slightly in his tea. Everybody in New York knew it but him. The waiters hurried across the street and told the waiters at Algonquin, who were waiting to see when it would finally dawn on him what he was drinking. And as the years went by, there got to be more and more urine and less and less tea. . . . And I, with my own ears, heard him at the 21 complaining to a waiter, saying, ‘Why can’t I get tea here as good as it is at The Royalton?’ That’s when I fell on the floor, you know.”

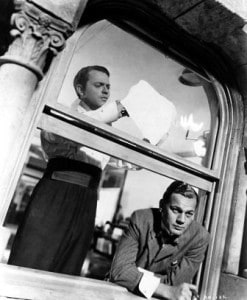

On The Third Man: “It’s full of ideas that everybody thought up on the set. Because Carol [Reed] was the kind of person who didn’t feel threatened by ideas from other people. A wonderful director. I really worshiped him. In Europe, the picture was a hundred times bigger than it was here. It was the biggest hit since the war. . . .

“Now, after this huge European success, it comes out in America—Selznick’s version—saying: ‘David O. Selznick presents The Third Man. Produced by David O. Selznick.’ About three of those credits. I took Alex[ander Korda] and David to dinner one night in Paris, right after it opened, and Alex said, ‘My dear David. I have seen the American titles.’ And David started to hem and haw, ‘Well, you know . . . ’ Alex said, ‘I only hope that I don’t die before you do.’ David said, ‘What do you mean?’ Alex replied, ‘I don’t want to think of you sneaking into the cemetery and scratching my name off my tombstone.’ ”

On Buster Keaton: “There’s nothing Chaplin ever made that’s as good as The General. I think The General is almost the greatest movie ever made. The most poetic movie I’ve ever seen.”

On Joseph Cotton: “The problem with Jo was that he was never a romantic leading man. He was a character actor. Nothing could make him a leading man. And that’s all he played in Hollywood. He looked stiff and wooden. Uncomfortable. It wasn’t because he got bad, it was because he was doing something outside his range. . . . Jo’s career was made not by Citizen Kane but Philadelphia Story on Broadway. Selznick picked him up and said, ‘We’ll have another Cary Grant.’ But nobody ever wrote him another part like that, you see. So that was his career—doing what he couldn’t do.”

On Joseph Cotton: “The problem with Jo was that he was never a romantic leading man. He was a character actor. Nothing could make him a leading man. And that’s all he played in Hollywood. He looked stiff and wooden. Uncomfortable. It wasn’t because he got bad, it was because he was doing something outside his range. . . . Jo’s career was made not by Citizen Kane but Philadelphia Story on Broadway. Selznick picked him up and said, ‘We’ll have another Cary Grant.’ But nobody ever wrote him another part like that, you see. So that was his career—doing what he couldn’t do.”

On Franklin Delano Roosevelt: “They were glorious [the FDR years]. Because you had a president who had made a hundred mistakes and never pretended he didn’t, and who was ready to try anything. And you had a fascinating cabinet, great personalities—everybody around him. And it was a happy time, even with all the misery. People were starving, but he pulled the country together.”

On Humphrey Bogart: “Bogart was a second-rate actor. Really a second-rate actor. He was a fascinating personality who captured the imagination of the world, but he never gave a good performance in his life. Only satisfactory. Just listen to a reading of any line of his. I saw Lloyd Nolan play [The Caine Mutiny] on the stage. He was hair-raising. He made Bogart look sick. There’s no comparison. Bogart in the thirties did the worst thing with Bette Davis [Dark Victory], when he had that Irish accent, that I’ve ever seen anybody do.”

On Humphrey Bogart: “Bogart was a second-rate actor. Really a second-rate actor. He was a fascinating personality who captured the imagination of the world, but he never gave a good performance in his life. Only satisfactory. Just listen to a reading of any line of his. I saw Lloyd Nolan play [The Caine Mutiny] on the stage. He was hair-raising. He made Bogart look sick. There’s no comparison. Bogart in the thirties did the worst thing with Bette Davis [Dark Victory], when he had that Irish accent, that I’ve ever seen anybody do.”

On actor vs. star: “And when you start to dissect a real star, one person will say they can act, another person will say they can’t. What is indelible is the quality of stardom. And whether it’s acting or not is a useless argument. Because the star thing is a different animal. It breaks all the rules.”

On John Barrymore: “You know, Jack was quite mad. His father died at forty-five, in an insane asylum. Jack would get drunk in order to be the drunk Barrymore, instead of the insane Barrymore. He would suddenly realize at the table that he didn’t know where he was or how he got there. A tragic situation.”

On film: “Essentially, I don’t believe in a film that isn’t a commercial success. Film is a popular art form. It has to have at least the kind of success that European and early Woody Allen movies had. People should be in those tiny theaters, lining up to see it.”

And so much more of the same. Welles hated the Irish but admired John Ford. He disliked, hated or felt abused by any number of people—Ruth Warwick, Charlie Chaplin, Pauline Kael, Elia Kazan, Irene Dunne and Peter Bogdanovich; though the number was appreciably smaller, there were others whom me liked or admired—John O’Hara, Joseph Cotton, Carol Reed and author Jacobo Timerman. There are others, but, yes, this list is shorter!

He appeared in four John Huston films, including Father Mapple in Moby Dick, but regarded his fellow director as “little more than a hack.” He had a continuing feud and animosity toward the “pompous” and “dreadful” John Houseman who grabbed, Welles said, undue credit for the work he shared with Orson in Citizen Kane and the Broadway musical The Cradle Will Rock. Welles sabotaged the party charades at Selznick’s house, and was rude to Richard Burton when he came over to his table at Ma Maison.

He appeared in four John Huston films, including Father Mapple in Moby Dick, but regarded his fellow director as “little more than a hack.” He had a continuing feud and animosity toward the “pompous” and “dreadful” John Houseman who grabbed, Welles said, undue credit for the work he shared with Orson in Citizen Kane and the Broadway musical The Cradle Will Rock. Welles sabotaged the party charades at Selznick’s house, and was rude to Richard Burton when he came over to his table at Ma Maison.

“It’s often the people who are not religious,” he said, “who are the most superstitious,” when some people believe the opposite is true. And speaking of “religion”: “I believe that we’re much healthier if we think of our selfishness as sin. Which is what it is: sin. Even if there is nothing out there except a random movement of untold gases and objects, sin still exists. . . . But I’ve never been the kind of religious person that thinks saying ‘Hail Mary’ is gonna get me out of it.”

As for the Louvre pyramid: “It looks ridiculous. . . . It’s a big piece of junk.” And about politicians: “A senator used to be a tremendous office. Now it’s really, more than it’s ever been, what the money buys. The special-interest thing.” This, already, in 1983!

An “authority” on just about anything, no topic was too small: “I made a discovery about the kiwi. That it’s the greatest fruit in the universe, but it’s ruined”—with a typical Wellesian proviso—“by all the French chefs of the world who cut it up into thin slices. You cannot tell what it tastes like unless you eat it in bulk.”

The variety, the uniqueness of his mind, even some of the absurdities—it’s tempting to continue the excerpts, to leave nothing for the readers to discover for themselves.

The variety, the uniqueness of his mind, even some of the absurdities—it’s tempting to continue the excerpts, to leave nothing for the readers to discover for themselves.

Besides Burton and that archbishop, any number of celebrities approached his table during these conversations—Jack Lemmon, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Susan Smith of HBO, “Swifty” Lazar and Gilles Jacob, president of the Cannes Film Festival. Toward some he was cordial, toward others dismissive, even confrontational.

The book could use an index, and the “Partial List of Characters”—people in Welles’ life—is, unfortunately, just that—way too partial; including the individuals’ dates would have been helpful. Not much can be said about the syntax: conversation is conversation. The exchanges between the two men, however, have been occasionally tailored for a more readable text. Equally readable are Biskind’s introduction and Jaglom’s epilogue, Welles’ passing five days after his last lunch with Jaglom.

In his introduction, Biskind writes, “His antic wit, stringent irony and enormous intelligence shine through these conversations and animate every word, making it difficult not to love the man.” Well, for some readers, and for those who already know this intense personality, “love” might be too demonstrative a word. Maybe “admire”? “Tolerate”? Perhaps, minus the admitted genius, Orson is too much like ourselves—the confluence of good and bad—and his larger-than-life persona might be too much of an extreme to unreservedly admire or emulate.

“I’m still sitting here like some kind of monument,” Orson Welles said at the end of these conversations, “but the moment will come when I’ll drop out of sight altogether, as though a trapdoor had opened, you know?”

“I’m still sitting here like some kind of monument,” Orson Welles said at the end of these conversations, “but the moment will come when I’ll drop out of sight altogether, as though a trapdoor had opened, you know?”

Not out of sight for a while, anyway. Jaglom’s conversations have perpetuated the Welles myth just a little further.

Sounds like a compelling read – did it alter your opinion of Welles? I haven’t opened my copy yet – but I recall off-handed quote somewhere accusing Jaglom of having tried hustling these tapes a long time; that it was recorded without OW’s knowledge. To read him trash his contemporaries (well, those of regular Hollywood galaxy; Welles was one onto his own) is intriguing and a little unsettling…. Was it worth the wait? Also, where is the final book of Callow’s three-part scalding encyclopedia on Welles? Did I sleep through it?

Thanks for providing the excerpts, they reminded me how interesting Welles was, not nice, but oh so talented and witty. I grew up when he was entertaining for being Orson Welles, and later discovered what he had done in his prime. The excerpts feel a bit like eavesdropping, but still fascinating. Oh, and thanks for reminding me of the Paul Masson ads.

Some of these made me laugh out loud. Ah, Orson! No shrinking violet, he.