“I swear there’s something inside.”—— Professor Lindenbrook (the insides of a lump of lava that start the whole journey)

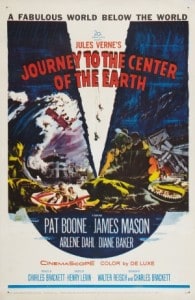

Two other Jules Verne-based movies have been discussed at this site—20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Mysterious Island. From 1959, and filmed between the two, Journey to the Center of the Earth has much to offer, aside from the shortcomings of some cardboard sets. It’s one of those “fun” movies, once called “general audience entertainment,” that they don’t make any more, a rip-roarin’ CinemaScope fantasy-adventure when widescreen was relatively new—and an intended gimmick to lure the growing viewers of Gunsmoke and Father Knows Best away from their TV sets.

[intlink id=”37″ type=”category”]James Mason[/intlink], who took second billing after the then current pop singer Pat Boone and just ahead of Arlene Dahl whose “movie star” treatment annoyed him, was then on the edge of the down slide of his career, having made North by Northwest that same year with Lolita to follow in 1962. Arlene Dahl, whose most significant film had been as long ago as The Bride Goes Wild in 1948 and always felt her talents lay in musical comedy, lent her best attribute, her beauty, but also rendered a respectable performance.

Not the least of the film’s pluses was one of Bernard Herrmann’s best fantasy film scores, with all the trademark “burps” and groans, signs of his love for building-block motifs. The music alone was perhaps the best reason to see—hear?—the movie.

Journey to the Center of the Earth may well be his best effort of the film’s generally middling director, Henry Levin, more famous for a brief string of sex comedies during the late ’50s, early ’60s—April Love, Holiday for Lovers, Where the Boys Are, Come Fly with Me. The wit in the script and the biting repartee are provided by veteran screenwriters Walter Reisch and Charles Brackett. Although the two did collaborate on several occasions during their respective careers, as in Ninotchka and Niagara, their more serious work was in partnership with others, Reisch as a co-writer in That Hamilton Woman and Gaslight, Brackett with Billy Wilder.

Except for the major addition of a requisite love interest, the Journey to the Center of the Earth script has fewer changes in the source material, in this case Verne’s 1864 novel, than is usual in movie makeovers. In the opening scene—changed from Hamburg to Edinburgh—it’s clear that Scotsman Oliver Lindenbrook (Mason) is the typical absent-minded professor. Having purchased a newspaper to read about his recent knighthood, he walks, unawares, into some parading bagpipers. Later, it’s learned that rudeness is also one of his characteristics.

Except for the major addition of a requisite love interest, the Journey to the Center of the Earth script has fewer changes in the source material, in this case Verne’s 1864 novel, than is usual in movie makeovers. In the opening scene—changed from Hamburg to Edinburgh—it’s clear that Scotsman Oliver Lindenbrook (Mason) is the typical absent-minded professor. Having purchased a newspaper to read about his recent knighthood, he walks, unawares, into some parading bagpipers. Later, it’s learned that rudeness is also one of his characteristics.

To celebrate his new honor, his geology students greet him with a song and a present. Among the students is young Alec McKuen (Boone), who presents him with a gift of his own, a lump of lava he saw in a curiosity shop. “A scholar’s choice,” Lindenbrook says. Although McKuen is on an every-other-day diet owing to his poverty, the professor insists he be at his home that evening for dinner.

McKuen has obviously been seeing Lindenbrook’s lovely niece Jenny (Diane Baker) as he complains that she has been ignoring his ardent advances. Before dinner, he expresses his affections with a song at the piano, “My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose,” words by Robert Burns and melody by James Van Heusen—not by Herrmann, who always pointed out that he was not a “pop” composer. It is Boone’s vocal highlight of the film, although two other Van Heusen songs were cut from the final print; Boone does later manage a few lines from “My Heart’s in the Highlands.”

McKuen has obviously been seeing Lindenbrook’s lovely niece Jenny (Diane Baker) as he complains that she has been ignoring his ardent advances. Before dinner, he expresses his affections with a song at the piano, “My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose,” words by Robert Burns and melody by James Van Heusen—not by Herrmann, who always pointed out that he was not a “pop” composer. It is Boone’s vocal highlight of the film, although two other Van Heusen songs were cut from the final print; Boone does later manage a few lines from “My Heart’s in the Highlands.”

When Lindenbrook hasn’t arrived for dinner, the guests, including the university’s dean (Alan Napier), visit his laboratory and find him working over the lump of lava. His assistant Paisley (Ben Wright) pours too much aqua regia into the furnace where the professor is attempting to dissolve the lava from whatever heavier object he believes to be inside, and the furnace explodes. The explosion throws everybody to the floor but does separate the lava from what was inside, a plumb bob. On the metal sphere, written in some Nordic language—perhaps in blood—is an inscription and a name, Arne Saknussem, an Icelandic explorer of three hundred years earlier. (In Verne’s novel, the translation came from a runic manuscript.)

Lindenbrook has, unwisely it will prove, written to Stockholm about his discovery, to Professor Göteborg (Ivan Triesault, Erich Mathis in Hitchcock’s Notorious), the foremost geological authority. While waiting for a reply, the plumb bob inscription has been translated. Saknussem relates that he is dying, but any one who descends the crater of the Icelandic volcano Snaefellsjokull (a real extinct volcano) can reach the center of the earth. Scratched on the plumb bob are three notches.

Lindenbrook has, unwisely it will prove, written to Stockholm about his discovery, to Professor Göteborg (Ivan Triesault, Erich Mathis in Hitchcock’s Notorious), the foremost geological authority. While waiting for a reply, the plumb bob inscription has been translated. Saknussem relates that he is dying, but any one who descends the crater of the Icelandic volcano Snaefellsjokull (a real extinct volcano) can reach the center of the earth. Scratched on the plumb bob are three notches.

In Iceland, Oliver and Alec are being shadowed at the volcano site by Göteborg, who has them kidnapped and thrown into an eider feather storehouse. Here occurs the most humorous scene in the film. The two captives assume the tapping from the other side of a wall is a fellow prisoner’s signal. Lindenbrook attempts to make contact by using Morse code, then French, then Russian before his ultimate embarrassment.

In Iceland, Oliver and Alec are being shadowed at the volcano site by Göteborg, who has them kidnapped and thrown into an eider feather storehouse. Here occurs the most humorous scene in the film. The two captives assume the tapping from the other side of a wall is a fellow prisoner’s signal. Lindenbrook attempts to make contact by using Morse code, then French, then Russian before his ultimate embarrassment.

The men are released by a husky Icelander, Hans Belker (Peter Ronson), the owner of a duck, Gertrude by name, whose nibbling at food was the source of the tapping!

In his efforts to buy equipment for the Lindenbrook expedition, Alec finds that all the needed materials have been cleared from the stores. In Göteborg’s hotel room, the two men find the man—dead—and all the equipment necessary for a trip to the center of the earth: self-generating lamps, picks, camping gear and breathing apparatuses. In a moment of silence for the dead man, “even if he was a thief,” Oliver says, the professor notices crystals on the dead man’s goatee—potassium cyanide.

In his efforts to buy equipment for the Lindenbrook expedition, Alec finds that all the needed materials have been cleared from the stores. In Göteborg’s hotel room, the two men find the man—dead—and all the equipment necessary for a trip to the center of the earth: self-generating lamps, picks, camping gear and breathing apparatuses. In a moment of silence for the dead man, “even if he was a thief,” Oliver says, the professor notices crystals on the dead man’s goatee—potassium cyanide.

As Lindenbrook observes, the person, or persons, who has been against them was even more against Göteborg. From the hotel clerk, they learn that Count Saknussem (Thayer David), a descendant of Arne, had been working for sometime with Göteborg in his room.

In Oliver’s initial meeting with the widow Carla (Dahl) of the dead man, he is rebuffed in his request for the equipment, insisting that Göteborg stole his idea of the expedition. Later, in reading her husband’s diary, she learns that, indeed, Göteborg was afraid Lindenbrook would “claim his rights.” In a change of heart, she agrees to give Oliver the equipment, the only condition being that she goes along.

Lindenbrook reluctantly agrees, and the four adventurers, with Hans as the guide, and accompanied by Gertrude, descend into the crater of the volcano, but not before the sunrise over the mountain Scartaris points to the entrance. Unknowingly, the group is being followed by the Count and his groom. Oliver and his party soon discover that the notches on the plumb bob are replicated on the floor of the caverns, signposts left by Arne.

The four explorers have many experiences, encountering both wonders and dangers. Right off, they survive a subterranean earthquake and a rolling boulder, with Lindenbrook running for his life, a precursor of Indian Jones’ near-death sprint in Raiders of the Lost Ark. They discover a phosphorescent pool, pass through a forest of giant mushrooms, nearly drown in a flood, endure an ocean storm and reach the magnetic center of the earth. To boot, they even discover the Lost “City” of Atlantis, as the continent is called here.

The four explorers have many experiences, encountering both wonders and dangers. Right off, they survive a subterranean earthquake and a rolling boulder, with Lindenbrook running for his life, a precursor of Indian Jones’ near-death sprint in Raiders of the Lost Ark. They discover a phosphorescent pool, pass through a forest of giant mushrooms, nearly drown in a flood, endure an ocean storm and reach the magnetic center of the earth. To boot, they even discover the Lost “City” of Atlantis, as the continent is called here.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea had its giant squid and Mysterious Island its assortment of overgrown creatures—a crab, a bird and a bee. So Journey to the Center of the Earth has its own beasts. Of course, the film is without the mind that devised the animatronic tentacles that made the squid so realistic or the expertise of Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion animation in Mysterious Island. The giant dimetrodons Lindenbrook and party encounter are actually rhinoceros iguanas with glued-on nuckual crests, and the enormous chameleon toward the end of the film?—— A painted tegu lizard.

“One night”—how would they know?!—when the party is preparing for sleep, Carla hears a noise. Oliver, in another of the film’s humorous moments, resents her complaints and suggests that Alec enter in his log that “a member of the expedition reported rats in the attic.” The explorers, of course, heard Count Saknussem.

“One night”—how would they know?!—when the party is preparing for sleep, Carla hears a noise. Oliver, in another of the film’s humorous moments, resents her complaints and suggests that Alec enter in his log that “a member of the expedition reported rats in the attic.” The explorers, of course, heard Count Saknussem.

A few hundred miles down the “trail,” Alec falls into a salt cavern and becomes lost, stumbling upon Saknussem, who demands he take the place of his dead groom. The Count shoots him in the arm and, thanks to some nineteenth-century invention, the last echo of the gun shot gives Lindenbrook the direction. The explorers are reunited, only to be held hostage by the Saknussem. Lindenbrook soon overpowers him, throwing salt in his face.

Lindenbrook convenes a trial for Saknussem and the jurors render a guilty verdict for his murder of Göteborg, but everyone refuses to be the executioner. Even here the humor persists. Toward Carla’s refusal, the professor says, “For weeks you’ve denied your sex. Now you fall back on it.” So it’s agreed that the Count will accompany them on their journey.

While everyone is exhausted and recovering from the storm at sea, Gertrude is eaten by the Count. When confronted by the party, he leans against a rock formation that has stood for eons. Suddenly it becomes fragile, collapsing and crushing the man. Much as when Oliver chipped a specimen from a cave wall and caused a water-gushing crack! Anyway——

While everyone is exhausted and recovering from the storm at sea, Gertrude is eaten by the Count. When confronted by the party, he leans against a rock formation that has stood for eons. Suddenly it becomes fragile, collapsing and crushing the man. Much as when Oliver chipped a specimen from a cave wall and caused a water-gushing crack! Anyway——

Coming upon the lost Atlantis, they find the skeleton of Arne Saknussem, whose arm points toward a volcanic chimney, presumably the way to the surface. The four travelers climb into an ancient altar stone—made of asbestos, luckily. Using some gunpowder—still potent after three hundred years?!—conveniently found in the skeleton’s haversack, the explosion displaces a boulder blocking the shaft, but also awakens a giant chameleon. The released lava that kills the reptile also provides a molten cushion for the altar stone as it is forced up the shaft at what must have been supersonic speed.

If the reader has stayed this long, no reason to suspend belief, common sense or fall back on anything so ridiculous as scientific reality! . . .

Not unexpectedly, all four space travelers, which is what they’ve become, fall safely back to earth, everyone into the sea except Alec, who falls, naked, into an Italian nunnery. In the final scene, Alec and Jenny have married and Oliver, in his fashion, proposes to Carla.

Not unexpectedly, all four space travelers, which is what they’ve become, fall safely back to earth, everyone into the sea except Alec, who falls, naked, into an Italian nunnery. In the final scene, Alec and Jenny have married and Oliver, in his fashion, proposes to Carla.

The big ingredient remaining, now, is the music.

Bernard Herrmann was known to have taken life—and movies—too seriously. He called the train in Murder on the Orient Express (1974) “a train of death” and thought Richard Rodney Bennett’s signature waltz unacceptable, without seeing or sensing the tongue-in-cheek approach to parts of that film. So in Journey to the Center of the Earth he wished—his words—“to create an atmosphere with absolutely no human contact.” No human contact? “This film had no emotion, only terror.” Terror?

And so the score he wrote adheres strongly, almost exclusively, to the natural visuals, however fake they often are—the volcano, the caverns, the ocean, the giant creatures, the flood, the mushroom forest. His music is of the impressionistic mode: three- and four-note motifs, endless brief sequences and instrumental imitations, ascending/descending scales, pedal points. No melody, no whistleable tune on the lips at the end of more than two hours of movie. Maybe, too, Herrmann was attempting to counteract the shortcomings of the sets, to have his music provide an extra hardness, starkness and, yes, more of an otherworldly feel, devoid of humans and human emotion.

And so the score he wrote adheres strongly, almost exclusively, to the natural visuals, however fake they often are—the volcano, the caverns, the ocean, the giant creatures, the flood, the mushroom forest. His music is of the impressionistic mode: three- and four-note motifs, endless brief sequences and instrumental imitations, ascending/descending scales, pedal points. No melody, no whistleable tune on the lips at the end of more than two hours of movie. Maybe, too, Herrmann was attempting to counteract the shortcomings of the sets, to have his music provide an extra hardness, starkness and, yes, more of an otherworldly feel, devoid of humans and human emotion.

In short, for the composer no humans seem to exist, certainly none of their humor. But there is—indisputably—much humor in the plot, especially the spats between Lindenbrook and Carla. Neither these nor any of the innumerable comic dialogues are reflected in the music. As the most obvious example, the especially long scene in the eider feather storehouse is unscored. Did the director, producer and composer, among themselves, decide that the scene did not need music? Perhaps, and perhaps it doesn’t require music; it seems to do well without it. Perhaps, though, Herrmann didn’t want to score it.

The only concession he makes to melody is the fleeting use of strings in the few allusions to Van Heusen’s melody for “My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose” and the bits that recall Edinburgh for two, anyway, of the explorers.

Of course the makeup of Herrmann’s orchestra, without the warm and melodic strings, should indicate the sound he wanted, and support his realization of that “terror.” All writers who write about Journey to the Center of the Earth quote the composer’s liner notes for his London (Decca) Phase-4 LP release in 1974. And what could be clearer or more succinct?

“I decided to evoke the mood and feeling of inner Earth by using only instruments played in low registers. Eliminating all strings, I utilized an orchestra of woodwinds and brass, with a large percussion section and many harps. But the truly unique feature of this score is the inclusion of five organs, one large cathedral and four electronic. These organs were used in many adroit ways to suggest ascent and descent [most spectacularly in the altar stone ascent], as well as the mystery of Atlantis.

“I decided to evoke the mood and feeling of inner Earth by using only instruments played in low registers. Eliminating all strings, I utilized an orchestra of woodwinds and brass, with a large percussion section and many harps. But the truly unique feature of this score is the inclusion of five organs, one large cathedral and four electronic. These organs were used in many adroit ways to suggest ascent and descent [most spectacularly in the altar stone ascent], as well as the mystery of Atlantis.

“For the scene involving the dangerous serpent [the giant chameleon], I resurrected an obsolete medieval instrument called a serpent, which has been dropped from contemporary orchestras.” In the original score, Don Cristlieb, more accustomed to the tenor saxophone, plays the instrument, which fellow film composer David Raksin said sounds like “a donkey with emotional problems,” or some might hear a deep, resonant belch, quite convincing for a monster.

Not surprising, the best parts of the score are the excerpts Herrmann selected for this album, later transferred to CD. He conducts the National Philharmonic, hand-picked from four or five of London’s best orchestras. Here are a few of the highlights of the album:

The main title is nothing more—— “Nothing more”: it’s quite an accomplishment, yet so simple. It’s nothing more than a descent down the scale, a three-note motif in the orchestra alternating with two notes from the organ, with, in between, low pedal points, all sinking deeper and deeper in register. The main title opens and closes with cymbal crashes, the four at the end reflecting the volcanic eruptions on screen. During the music, the camera has moved gradually from outer space and a view of the earth’s sphere into the deepest bowels of the planet and, presumably, the fire of its core.

“The Mountain Top and Sunrise” begins with a forte trumpet motif, a call from on high, then the quiet strumming of harps against ascending woodwinds—louder and louder—which are joined by ascending brass. Added is the eruption of the organs, including the cathedral organ. Quiet returns with the strumming of the harps. Some listeners may hear in all this something of Richard Strauss’ tone poem An Alpine Symphony, which, coincidentally, begins with a sunrise.

“Salt Slides,” when McKuen falls through a crevice into a salt cavern, is a series of frantic trills and flutter-tonguing in the woodwinds and brass, with harp glissandos. Blotches of large chords interrupt the proceedings. This is a very short sequence, as are many of the episodes; as is the nature of adventure films, one scene moves quickly to another and the requirements of a composer’s tonal palette change.

“Salt Slides,” when McKuen falls through a crevice into a salt cavern, is a series of frantic trills and flutter-tonguing in the woodwinds and brass, with harp glissandos. Blotches of large chords interrupt the proceedings. This is a very short sequence, as are many of the episodes; as is the nature of adventure films, one scene moves quickly to another and the requirements of a composer’s tonal palette change.

“The Shaft and Finale” is a reversal of the opening main title where the sense had been of an enormous orchestral descent. Here the effect is of a tremendous ascent. For the longest time it seems, the registers of all the instruments rise through the scale, sustained by organ pedal points, themselves all the while ascending in blocks. The screen is alternating between full shots of obviously stiff, unmoving dummies in a little saucer and closeups of the actual actors rotating in their asbestos dish, while at the same time being forced upward through the shaft. The moment the travelers are spewed from the volcano becomes a palatable release of tension, both for the viewer and in Herrmann’s orchestra.

Wow! What a fantastic write-up on a classic adventure film. “Journey to the Center of the Earth” has long been one of my favorite adventure movies, not only for its great “feel” ( the fabulous sets by Lyle Wheeler really transport you to the 1800s ) but because it traverses alot of territory and plot in a relatively short about of time. After watching this film I was anxious to read the original Verne novel…but was disappointed, there was no Arlene Dahl character, nor a concertina playing Pat Boone! Thank you for this great review.

Enjoyed your review. Considering the film is over 50 years old, the special effects are pretty spectacular,I think.

Bernard Hermann’s brilliant score creates such a marvellous atmosphere for the story.

I could have done without Pat Boone vainly trying to be Scottish!