“Tell me, Mrs. Wright, does your husband interfere with your marriage?”—— Oscar Levant to Joan Crawford

Joan Crawford hit her peak in three consecutive years in three consecutive films, all for Warner Brothers. For Mildred Pierce, in 1945, she received her only Oscar among three nominations during an almost fifty-year career, here playing against type as a down-and-out waitress. Despite the Oscar, many viewers found her less than totally convincing in the role: it just wasn’t who she was. Perhaps the weakest of the three films, one of several major flaws was the over-acting of Ann Blyth as Crawford’s daughter and the weak writing of her part.

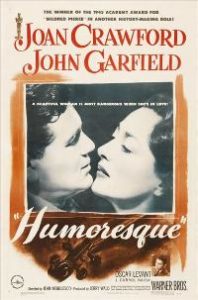

More comfortable with herself as an actress, Crawford in Humoresque in 1946 was perhaps never better in playing the kind of role that had solidified her career, the supposed sophisticated woman tortured by demons and overindulgence, whether it’s booze, men or power, or all three. Strangely enough, earlier that year the studio had released another film about brooding and scheming classical musicians. With Bette Davis and Claude Rains, Deception is better scripted and more technically astute about music, but is otherwise surpassed by Humoresque.

The Crawford film is simply a better movie as entertainment, made in Warner Bros.’ slickest style, thanks to director Jean Negulesco, cinematographer Ernest Haller and a script by Clifford Odets and Zachary Gold. The source is a 1919 short story by Fannie Hurst, high-class soap opera and here lifted even higher.

Possessed, which many regard as Crawford’s best performance, came in 1947. Here, more so than even in Humoresque, she could employ the full range of acting pyrotechnics in portraying schizophrenia, obsessive love, insanity and, finally, murder. Oscar-nominated for her role as Louise Howell, the two men in her life were Raymond Massey, the supportive husband, and her obsession, Van Heflin, the scoundrel who warps and changes her life.

In Humoresque—so named after the seventh in a set of nine piano pieces by Czech composer Antonín Dvorák—the husband (Paul Cavanagh) is not so much supportive as “understanding,” maybe “dismissive,” of his wife’s sexual indiscretions. Helen Wright (Crawford), an alcoholic and neurotic patroness of the arts, is much impressed by the violin playing of Paul Boray (John Garfield) when introduced at one of her lavish parties by his friend and co-music student Sidney Jeffers (Oscar Levant).

But to backtrack. Earlier in the film—told in flashback—Paul has matured now from a young lad (Robert Blake) and gone against his father’s (J. Carrol Naish) protests to take up the violin. As a young music student, he has relations with other members of the orchestra besides Sid. The school head (John Abbott, a mediocre cellist in Deception) does what he can to guide Paul’s instructions, and later his agent (Richard Gaines) arranges a public concert.

But to backtrack. Earlier in the film—told in flashback—Paul has matured now from a young lad (Robert Blake) and gone against his father’s (J. Carrol Naish) protests to take up the violin. As a young music student, he has relations with other members of the orchestra besides Sid. The school head (John Abbott, a mediocre cellist in Deception) does what he can to guide Paul’s instructions, and later his agent (Richard Gaines) arranges a public concert.

Cello student Gina (Joan Chandler) confesses her love for him, and Paul, though overly ambitious and his mind set on becoming a concert violinist, seems to reciprocate her feelings. This is before he comes under the influence of Mrs. Wright. (Chandler, by the way, after her début in Humoresque and an appearance in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, went into television, soon retired and died at the early age of fifty-five.)

After Sid has accompanied Paul in a piano/violin arrangement of the finale of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, Sid pompously observes: “From now on, you can sign all your letters ‘fiddle player.’ I have spoken. . . . Little too brash, little over-brilliant. You need more restraint. . . . You have all the characteristics of a successful virtuoso. You’re self-indulgent, self-dedicated and the hero of all your dreams.”

Much as the year before in Rhapsody in Blue, another Warner Bros. music saga, Levant has some of the best, certainly the most comical and satirical lines in Humoresque. “It isn’t what you are, it’s what you don’t become that hurts.” “I don’t like to play the piano. It makes me too attractive.” “I hate cold showers. They stimulate me and then I don’t know what to do.” “I envy people who drink. At least they know what to blame everything on.”

On The Tonight Show during Jack Paar’s tenure, when Jack asked Levant what he did for exercise, the neurotic hypochondriac famously replied, “I stumble, and then I fall into a coma.” A classical pianist who died in 1972, Levant knew George Gershwin and is still remembered for his interpretations of his friend’s Rhapsody In Blue and the Concerto in F. Some of the recordings are still available.

Believing the rich and influential Helen can help him and feeling better about himself in her fascinating world of high society, Paul is drawn into her web and succumbs to an affair. She, however, is controlling and feels slighted when Paul’s obligations to his music take him away from her: “Did you think,” she says, “you could go away for weeks, almost months, never call or write, and come back to find me hanging in a clothes closet like a suit that you might put on some day a year from now?”

Believing the rich and influential Helen can help him and feeling better about himself in her fascinating world of high society, Paul is drawn into her web and succumbs to an affair. She, however, is controlling and feels slighted when Paul’s obligations to his music take him away from her: “Did you think,” she says, “you could go away for weeks, almost months, never call or write, and come back to find me hanging in a clothes closet like a suit that you might put on some day a year from now?”

Paul’s mother (Ruth Nelson) is adamant that this life is not for him, either Mrs. Wright or the world she inhabits.

The film drama comes to a head. During a rehearsal, Helen passes a note to Paul, possibly to announce that her husband, suspicious of her latest infidelity, has asked for a divorce. Paul disregards the note and continues with the rehearsal, symbolic, at least to the possessive woman, that his music comes first. At a bar, she is tormented by a singer’s “Embraceable You.” (It is reminiscent of Dark Victory when Davis, knowing she is dying, is tormented by another song, “Oh, Give Me Time for Tenderness.”) Later, when Paul arrives to pick up Helen, she is suddenly cold toward him.

Still later, having visited Paul’s home and received only resentment from Mother Boray, Helen is at her beach house listening to a radio broadcast of Paul playing a violin arrangement (instead of the called-for soprano voice) of the “Liebestod” from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Helen seems all the more distraught and confused. More considerate than usual perhaps, she feels her love can only harm Paul and his career. She walks into the ocean, elegantly gowned, of course, accompanied by the radio music, now front and center from the screen. Not coincidentally, the cliché thinkers of Hollywood though the music appropriate, a real breakthrough. After all, the “Liebestod,” or “love-death,” is Isolde’s orgasmic farewell to Tristan, the two lovers dying in each other’s arms.

Still later, having visited Paul’s home and received only resentment from Mother Boray, Helen is at her beach house listening to a radio broadcast of Paul playing a violin arrangement (instead of the called-for soprano voice) of the “Liebestod” from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Helen seems all the more distraught and confused. More considerate than usual perhaps, she feels her love can only harm Paul and his career. She walks into the ocean, elegantly gowned, of course, accompanied by the radio music, now front and center from the screen. Not coincidentally, the cliché thinkers of Hollywood though the music appropriate, a real breakthrough. After all, the “Liebestod,” or “love-death,” is Isolde’s orgasmic farewell to Tristan, the two lovers dying in each other’s arms.

But Paul does not die. Unlike the self-absorbed and parasitic Mrs. Wright, he’s made of stronger stuff. The flashback is over, and Humoresque returns to its opening where Paul is preparing for a concert. He tells his friend Sid to assure his agent that he will be present and ready.

The film has its share of popular music—“Embraceable You,” “You Do Something to Me,” “My Heart Stood Still” and other familiar tunes, performed by Peg La Centra—but the lofty subject matter of the film needs something stronger—classical music, in all its truncated, rearranged and excerpted form.

Franz Waxman’s nomination for Best Score is something of a mystery, even at the time, since the music, far from original to the film, is often classical. Much of what is heard as actual score is Waxman’s arrangements of music by others. The main title, for instance, uses Dvorák’s Humoresque No. 7 in a lush orchestral version. Besides the Mendelssohn and the Wagner, there is much source music, either “played” by Garfield or with Levant at the piano: a couple of Gershwin preludes, a Chopin etude, Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole, the Brahms Violin Concerto and “Flight of the Bumblebee” from Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Tale of Tsar Saltan. For the rehearsal scene, Waxman arranged his own Carmen Fantasie. Concert violinist Isaac Stern did the actual playing on the soundtrack.

Franz Waxman’s nomination for Best Score is something of a mystery, even at the time, since the music, far from original to the film, is often classical. Much of what is heard as actual score is Waxman’s arrangements of music by others. The main title, for instance, uses Dvorák’s Humoresque No. 7 in a lush orchestral version. Besides the Mendelssohn and the Wagner, there is much source music, either “played” by Garfield or with Levant at the piano: a couple of Gershwin preludes, a Chopin etude, Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole, the Brahms Violin Concerto and “Flight of the Bumblebee” from Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Tale of Tsar Saltan. For the rehearsal scene, Waxman arranged his own Carmen Fantasie. Concert violinist Isaac Stern did the actual playing on the soundtrack.

Another classical violinist, Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg, has devoted an entire album to the music from Humoresque, including the Wagner in its aberrant version, the complete Carmen Fantasie as well as the songs by Porter, Gershwin, Rodgers, Warren and Hanley. The CD cover depicts a ’40s-style telephone, a military dog tag, an alarm clock and a smoker’s litter—unlit cigarettes, a matchbook and an ashtray full of butts. Itzhak Perlman has released two CDs devoted to movie music—mostly orchestral pieces arranged to include solo violin—but neither contains any music from Humoresque, though he has recorded the Dvorák in strictly classical releases.

Another classical violinist, Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg, has devoted an entire album to the music from Humoresque, including the Wagner in its aberrant version, the complete Carmen Fantasie as well as the songs by Porter, Gershwin, Rodgers, Warren and Hanley. The CD cover depicts a ’40s-style telephone, a military dog tag, an alarm clock and a smoker’s litter—unlit cigarettes, a matchbook and an ashtray full of butts. Itzhak Perlman has released two CDs devoted to movie music—mostly orchestral pieces arranged to include solo violin—but neither contains any music from Humoresque, though he has recorded the Dvorák in strictly classical releases.

Because of the amount of arranged music, it is not surprising that Waxman failed to win the Oscar for Best Score in 1946. Besides, the year was unusually strong in the category—then of the wall-to-wall variety, before the influence of jazz, pop tunes and sparse scoring. The other nominees were Miklós Rózsa’s The Killers, Bernard Herrmann’s Anna and the King of Siam, William Walton’s Henry V and the winner, and justly so, though strangely neglected in its recorded history, Hugo Friedhofer’s The Best Years of Our Lives.

If Crawford did herself honor in Humoresque, John Garfield as Paul Boray did even better, perhaps the most convincing and concentrated role of his career. The strength and credence of his intensity is quite an accomplishment, considering his many other similar parts—in just his two previous films alone, The Postman Always Rings Twice and Nobody Lives Forever. Nor would the intensity lessen in the few short years he had left—he would die of a heart attack at age thirty-nine. In Body and Soul (1947), he received his second Oscar nomination, not, as is often assumed, for his other strong performance that year in Gentleman’s Agreement. He received his first Oscar nomination, for Supporting Actor, for his second film, Four Daughters. The length of his career was less than half the length of Crawford’s.

If Crawford did herself honor in Humoresque, John Garfield as Paul Boray did even better, perhaps the most convincing and concentrated role of his career. The strength and credence of his intensity is quite an accomplishment, considering his many other similar parts—in just his two previous films alone, The Postman Always Rings Twice and Nobody Lives Forever. Nor would the intensity lessen in the few short years he had left—he would die of a heart attack at age thirty-nine. In Body and Soul (1947), he received his second Oscar nomination, not, as is often assumed, for his other strong performance that year in Gentleman’s Agreement. He received his first Oscar nomination, for Supporting Actor, for his second film, Four Daughters. The length of his career was less than half the length of Crawford’s.

Unlike Garfield’s, Joan Crawford’s career suffered the decline typical of so many of Hollywood’s biggest stars from her era, like Davis, and like Davis—the two women hated one another—she descended to grade Z horror films, titles which ring like career knells: Strait-Jacket, Berserk and Trog. Her earliest film in this genre, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, is surprisingly good. It costarred her nemesis Davis, their animosity now personified on screen. Davis received an Oscar nomination. Joan, as the abused sister, was passed over.

Oh boy – I can’t believe I’ve never seen this one, and I call myself a Joan Crawford fan! It looks fascinating and I really must make a more concerted effort to see it.

Excellent review!