“Confidentially, I think you’re a bit of a stinker, too.”— Michael Redgrave to Margaret Lockwood in the early part of the movie

“Confidentially, I think you’re a bit of a stinker, too.”— Michael Redgrave to Margaret Lockwood in the early part of the movie

Unlike John Huston who would frequently direct some light fare after a “heavy” picture, Alfred Hitchcock would often follow a dark film with an even darker one, and the over-all landscape of his oeuvre shows a gradual darkening, often meaning a growing explicitness. After all, did not The Birds follow Psycho? It would be hard, though, to know which is the more frightening—the menace in both is often unseen. And after two films of political intrigue, Torn Curtain and Topaz, both far below Hitch’s high standards, came his most sexually vulgar effort, Frenzy.

But, no, this thinking isn’t always correct. The reverse is just as often true. After a warning, in 1940, that World War II could spread to American shores in Foreign Correspondent, the director relaxed with Mr. and Mrs. Smith, his only romantic comedy. It was more as a favor to Carole Lombard than any urgent need of expression. Fifteen years later, after two fluffy films, To Catch a Thief and The Trouble with Harry, came the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much, which, despite the advantages of VistaVision and Technicolor, many regard as inferior to the 1934 original.

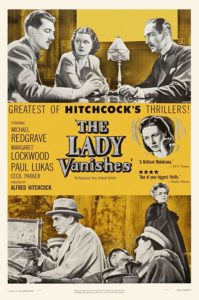

Though not totally unexpected—the previous movie, Young and Innocent, was also a comedy and a “journey” film—The Lady Vanishes remains a breed all its own, so light-hearted and, to a degree, so implausible in plot that it’s difficult to believe it ranks as one of Hitchcock’s masterpieces, but a masterpiece it is. François Truffaut, who conducted an extended interview with Hitch in 1962, later published in book form, considered The Lady Vanishes the most typical of all the director’s films.

As Truffaut said during the interview, “They show [The Lady Vanishes] very often in Paris. Sometimes I see it twice in one week. Since I know it by heart, I tell myself each time that I’m going to ignore the plot, to examine the train and see if it’s really moving, or to look at the transparencies, or to study the camera movements inside the compartments. But each time, I become so absorbed by the characters and the story that I’ve yet to figure out the mechanics of the film.”

As Truffaut said during the interview, “They show [The Lady Vanishes] very often in Paris. Sometimes I see it twice in one week. Since I know it by heart, I tell myself each time that I’m going to ignore the plot, to examine the train and see if it’s really moving, or to look at the transparencies, or to study the camera movements inside the compartments. But each time, I become so absorbed by the characters and the story that I’ve yet to figure out the mechanics of the film.”

The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps are the best known of Hitch’s pre-Hollywood sound films, nestled, as they are, among some darker works—Secret Agent, the original The Man Who Knew Too Much and perhaps the bleakest of the ’30s films, Sabotage. Coincidentally, The Lady Vanishes was followed by one of Hitch’s great failures, Jamaica Inn, his last film before leaving England for the greater opportunities and technical advantages of Hollywood.

His first film in Tinsel Town, despite the unwanted, and resented, meddling of David O. Selznick—and that Hitch himself never regarded it as a “Hitchcock picture”—was a smash hit, financially and critically, even beyond Selznick’s wildest dreams, and he always dreamed big. Rebecca earned Hitchcock the first of his five Oscar nominations, none earning a statuette. Two of the ten other nominations for Rebecca produced wins—for Best Picture of 1940 and George Barnes’ B&W cinematography.

The Lady Vanishes is based on Ethel Lina White’s novel The Wheel Spins. Hitch made a few changes, including the ending, and added a gunfight—and more humor.

The Lady Vanishes is based on Ethel Lina White’s novel The Wheel Spins. Hitch made a few changes, including the ending, and added a gunfight—and more humor.

After an avalanche has forced several groups of travelers to spend the night in a hotel in the Balkans where the guests either become friends or establish a few resentments, they board a train for London. Returning home to her fiancé after a vacation is a young English woman, Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood), who encounters a rude musicologist, Gilbert (Michael Redgrave), and a charming old governess and music teacher, Miss Froy (Dame May Whitty), whom Iris likes instantly.

When departing the train station, Iris had been struck on the head by a flowerpot pushed from a windowsill, seemingly intended for Miss Froy. Dr. Hartz ([intlink id=”31″ type=”category”]Paul Lukas[/intlink]) suggests that the blow has caused her to hallucinate, that the said Miss Froy, whom Iris insists has disappeared from the train, never existed. All the passengers deny ever seeing the lady—two cricket enthusiasts, Charters and Caldicott (Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne), a barrister (Cecil Parker) traveling with his mistress (Linden Travers), a black-attired baroness (Mary Clare), a nun (Catherine Lacey), a magician (Philip Leaver) and a few others.

Iris turning to Gilbert for help seems somehow natural in that typically Hitchcockian way and they gradually become more cordial. Gilbert at first doubts her about a disappearing old lady, but gradually little things support her—the nun who wears high heels; a strange patient, head wrapped in bandages, of the doctor’s; and Iris’ insistence that the missing woman had written “Froy” in the dust on a train window, though the letters unaccountably vanish before Gilbert can see them. Gilbert finally believes her when he sees a Harriman’s tea label plastered to a window pane when the cook throws out the kitchen garbage. That brand was the only tea Miss Froy would drink, and she had given a packet to the waiter.

Iris turning to Gilbert for help seems somehow natural in that typically Hitchcockian way and they gradually become more cordial. Gilbert at first doubts her about a disappearing old lady, but gradually little things support her—the nun who wears high heels; a strange patient, head wrapped in bandages, of the doctor’s; and Iris’ insistence that the missing woman had written “Froy” in the dust on a train window, though the letters unaccountably vanish before Gilbert can see them. Gilbert finally believes her when he sees a Harriman’s tea label plastered to a window pane when the cook throws out the kitchen garbage. That brand was the only tea Miss Froy would drink, and she had given a packet to the waiter.

That no one has seen Miss Froy is indeed a conspiracy of sorts. The cricket pals don’t want anything to delay their making the game and the barrister fears the publicity an inquiry into a missing woman might produce. But some of the others have lied because they are involved in the disappearance of the lady; indeed, the bandaged and sedated woman in Dr. Hartz’ compartment is Miss Froy.

When the snooping Iris and Gilbert become a threat, the doctor drugs them, but in another Hitchcock license they miraculously overcome falling asleep and free Miss Froy, substituting an impostor (Josephine Wilson), complete with the concealing bandages.

When the snooping Iris and Gilbert become a threat, the doctor drugs them, but in another Hitchcock license they miraculously overcome falling asleep and free Miss Froy, substituting an impostor (Josephine Wilson), complete with the concealing bandages.

Dr. Hartz has the train detoured to a forest siding where more of his cohorts await, and in a gunfight they attempt to remove from the train Miss Froy—the as yet undetected substitute, that is. The cowardly barrister, believing himself a spokesman for the entire group, attempts to surrender and is killed. In an interesting surmise, is it possible, the barrister’s name being Todhunter and “tod” meaning death in German, that this is a form of Hitch’s name-playing? The barrister and the nun are the only passengers who die.

Helped out a window by Gilbert, Miss Froy escapes through the woods.

Turns out the old lady is a British secret agent returning to London with a message encoded in a tune. She has Gilbert memorize it in case she doesn’t make it. This tune bearing a message, like the uranium in the wine bottles in Notorious or the microfilm in North by Northwest or Marion Crane’s stolen money in Psycho, is the typical Hitchcock “MacGuffin,” that which seems important to the story, and which the characters are after, but which is of little interest to the audience or to the success of the film.

Gilbert and Caldicott commandeer the train, leaving in its dust Dr. Hartz, who gentlemanly philosophies about his defeat.

Gilbert and Caldicott commandeer the train, leaving in its dust Dr. Hartz, who gentlemanly philosophies about his defeat.

Gilbert and Iris do make it to London. Seeing her fiancé waiting for her on the station platform, she avoids him by slipping into an unoccupied train coach. The two share their first and only kiss and in the next scene are discussing where to spend their honeymoon.

For sometime Gilbert has been constantly humming the tune so as not to forget it, and when he and Iris are about to be ushered into the espionage office to deliver the “message,” he has forgotten the melody. Then they hear the tune on a piano beyond the door. It’s Miss Froy and the three joyfully embrace.

In his first movie role, Michael Redgrave is more than excellent, which is surprising since he was uninterested in a movie career and was then starring in a John Gielgud production of The Three Sisters. “To be honest,” he later said, “I suppose I was something of an intellectual snob at the time, and film acting here in England was not regarded very highly. No serious actor or actress concentrated on film work or appeared very often before the cameras. I think Hitch . . . decided to cut me down to size. The first day of shooting he came over to me and said, ‘You know, don’t you, that Robert Donat wanted to play this role in the worst way.’ I suppose it was meant to make me feel a little unwelcome, but it didn’t. I really wasn’t trying very hard anyway.”

It is precisely this unassuming nonchalance—the laid-back delivery and relaxed body language—and what Hitch called Redgrave’s “throwaway” acting style that suited so well the detached character of Gilbert. An extension of this was a natural flair for comedy, especially effective in the baggage car where he dons several hats from the magician’s trunk and impersonates Sherlock Holmes, an old English gentleman and a dotty schoolmaster.

It is precisely this unassuming nonchalance—the laid-back delivery and relaxed body language—and what Hitch called Redgrave’s “throwaway” acting style that suited so well the detached character of Gilbert. An extension of this was a natural flair for comedy, especially effective in the baggage car where he dons several hats from the magician’s trunk and impersonates Sherlock Holmes, an old English gentleman and a dotty schoolmaster.

The three leading film veterans hold up their ends well. The attractive Margaret Lockwood is perfect as the distraught young lady in distress and soon establishes an easygoing charisma with Redgrave. As Leslie Halliwell has written, she “was an appealing ingénue”—as she clearly is here—“in the ’30s, a rather boring star villainess in the ’40s and later a likeable character actress of stage and TV.”

Dame May Whitty would soon go to Hollywood, and if she perhaps never again played as large a role as the one in The Lady Vanishes, she is nonetheless remembered for many small parts as endearing old ladies, often of the meddling or imperial variety—in Suspicion, Mrs. Miniver and The Constant Nymph. She, in fact, has the last line in Gaslight (1944) when she sees Ingrid Bergman and Joseph Cotton embraced: “Well!”

The Hungarian Paul Lukas, who adapted well to his roles as he aged, did his best work in Dodsworth, Confessions of a Nazi Spy and received an Oscar for Watch on the Rhine in 1944.

The Hungarian Paul Lukas, who adapted well to his roles as he aged, did his best work in Dodsworth, Confessions of a Nazi Spy and received an Oscar for Watch on the Rhine in 1944.

The epitome of English gentlemen abroad, Radford and Wayne were something of a hit in their first appearance as Charters and Caldicott. With snooty impatience and stuffy self-importance, their humor occupies a good portion of The Lady Vanishes. They would reappear as the same characters in several later films, including Cook’s Tour, Millions Like Us and Night Train to Munich, also starring Lockwood.

In so light a film as The Lady Vanishes, it may be a surprise to find that sex plays its part. And then maybe not a surprise, for, after all, Hitchcock had an active sense of humor, often risqué, especially toilet humor, and loved practical jokes, sometimes of a injurious nature. In an early scene, a waiter enters the room of Iris and her two traveling companions and Hitch renders close-ups of the girls’ legs, Lockwood dancing on a table in her underwear. When Gilbert is evicted from his room because Iris has complained of the noise, he invades hers, opens his suitcase on her bed, removes some pajamas and asks which side of the bed she prefers.

In so light a film as The Lady Vanishes, it may be a surprise to find that sex plays its part. And then maybe not a surprise, for, after all, Hitchcock had an active sense of humor, often risqué, especially toilet humor, and loved practical jokes, sometimes of a injurious nature. In an early scene, a waiter enters the room of Iris and her two traveling companions and Hitch renders close-ups of the girls’ legs, Lockwood dancing on a table in her underwear. When Gilbert is evicted from his room because Iris has complained of the noise, he invades hers, opens his suitcase on her bed, removes some pajamas and asks which side of the bed she prefers.

When Charters and Caldicott are sharing the maid’s room, the maid starts to undress in front of them. Earlier, Charters had told the hotel manager, “You can’t expect the two of us to sleep in the maid’s room.” “Don’t get excited,” says the manager. “I’ll move the maid out.” Later, when the maid comes in, the two men are in bed together, Caldicott shirtless.

Louis Levy’s “score”—hardly a proper use of the word here—is limited to the main title, with its fanfare opening and a string serenade, and a return of the serenade during the three-character embrace in the final seconds. In between, Mr. Levy is never heard. The end cast, supported by music, repeats the cast list shown after the main title.

With no disrespect toward the composer’s contribution, however small, the more important music is source, music that is part of the plot in all its forms, sometimes in the dialogue. In the introduction of the two cricket pals, Caldicott blames Charters for missing a train in Budapest because Charters insisted on standing for what he thought was Hungary’s national anthem. “It’s always been my contention,” Caldicott says, “that the Hungarian Rhapsody [of Liszt, but which one?] is not that country’s national anthem. We were the only two standing.”

With no disrespect toward the composer’s contribution, however small, the more important music is source, music that is part of the plot in all its forms, sometimes in the dialogue. In the introduction of the two cricket pals, Caldicott blames Charters for missing a train in Budapest because Charters insisted on standing for what he thought was Hungary’s national anthem. “It’s always been my contention,” Caldicott says, “that the Hungarian Rhapsody [of Liszt, but which one?] is not that country’s national anthem. We were the only two standing.”

In the hotel, Gilbert as a researcher of indigenous music, plays folk music on his clarinet and sets the tempo for a clogging dance by some of the guests. While at the hotel, Miss Froy is serenaded outside her window by a singer whose death in the shadows by a pair of strangling hands is never explained or mentioned thereafter. And then there is the “message” tune itself, and, of course, the rhythms of the train—the “clickety-clack” as it moves over the rails and the “chug-chug” of the steam engine.

All this is a reminder of how important music was to Hitchcock as a director and planner of movies, not only a suitable accompanying score but source music as a sometimes plot-turning ingredient—the music hall tune which Robert Donat can’t get out of his head in The 39 Steps, an assassination attempt timed to a cymbal crash in The Man Who Knew Too Much, the emphasis on “Three Blind Mice” during a children’s game in Young and Innocent and the ballet interrupted by a fire in Torn Curtain —pirouettes and arabesques choreographed for Tchaikovsky’s non-ballet music in Francesca da Rimini.

Judging by the opening credits, it’s obvious that Hitchcock is on a tight budget, as in most of his British films. The camera pans from a matte mountain scene to a model of the hotel and, beside it, the railway station and tracks. An already suspicious viewer might notice that the people on the platform do not move, and as the camera approaches the hotel, a toy car is pulled so as to appear arriving at the unseen front of the hotel.

Judging by the opening credits, it’s obvious that Hitchcock is on a tight budget, as in most of his British films. The camera pans from a matte mountain scene to a model of the hotel and, beside it, the railway station and tracks. An already suspicious viewer might notice that the people on the platform do not move, and as the camera approaches the hotel, a toy car is pulled so as to appear arriving at the unseen front of the hotel.

As in so many Hitchcock movies, the opening panning shot, still unbroken, moves to focus on a window—as in Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, Psycho, Frenzy for instance—and, with a dissolve, continues inside the hotel lobby where Miss Froy is coming down the entrance stairs to the desk clerk/hotel manager (Emile Boreo).

The inspiration for these musings was the PBS premiere of another “Masterpiece Mystery” installment from the British. After the disappointing Murder on the Orient Express in 2010 with David Suchet, many viewers had reason to be skeptical of yet another take of The Lady Vanishes. Supposedly more faithful to the book, not Hitch’s version, it was pretty much the same plot. And, at the same time, a totally different enterprise. To be succinct, it was pathetic, an expensive and somewhat fruitless endeavor, devoid of most of the humor that helped make Hitch’s version a masterpiece—and so watchable besides.

Miss Froy was played by Selina Cadell, pharmacist Mrs. Tishell in Doc Martin. Okay, good so far. The role of Iris Henderson, portrayed by Tuppence Middleton, came across as a totally unsympathetic, even annoying heroine, utterly charmless. Her character—though here perhaps more faithful to the book—is spoiled, privileged and a bit of a pain. Supposedly scripted to become kinder at film’s end, she remained as unlikable as before; never, for a moment, as appealing as Margaret Lockwood.

By contrast, in the Redgrave part, Tom Hughes, who is currently starring in Silk on “Masterpiece Mystery,” was a much more sympathetic character, not the snob his predecessor played in the beginning. Why this Gilbert was attracted to this Iris seems an enigma; his tolerance of the indifferent, flighty and selfish bimbo was commendable. Present in a minor role, and largely wasted with sporadic one-liners, was Stephanie Cole from Waiting for God and Doc Martin.

And that ever-moving camera, down corridors, around corners, through doors!—to the point of dizziness. And those tight close-ups—ugh! But that’s TV. At least in the past, the close-ups were justified because of the small screen, but now that TV screens have become larger—enormous—why the continuance of the practice? Maybe because, conversely, laptops and hand-held toys have regressed to the small screen.

And that ever-moving camera, down corridors, around corners, through doors!—to the point of dizziness. And those tight close-ups—ugh! But that’s TV. At least in the past, the close-ups were justified because of the small screen, but now that TV screens have become larger—enormous—why the continuance of the practice? Maybe because, conversely, laptops and hand-held toys have regressed to the small screen.

By all means, forget Tuppence Middleton and her fellow passengers—and, for that matter, the 1979 Elliott Gould-Cybill Shepherd account. Watch instead Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes to best appreciate the art of film.