A tennis star plays a match with murder!

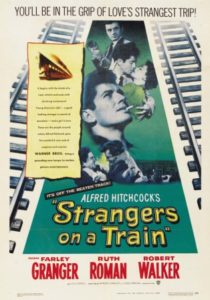

Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, clearly among his five greatest films, begins and ends with a train ride and with the line, “I beg your pardon, but aren’t you Guy Haines?” And during the one hundred minutes or so in between beginning and end, star tennis player Guy Haines (Farley Granger) has the nightmare of his life. On a train from Washington, D.C., he by chance meets Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker) whose small talk reveals a surprising knowledge of his personal life. From reading the society page, Bruno knows, for instance, that the celebrity is seeking a divorce from an obstinate wife so as to marry a senator’s daughter.

Over drinks and a meal of overdone lamb chops, Bruno casually makes a most unusual proposal, an exchange that he says would benefit both. What if Guy had someone he wanted to get rid of, say, this wife of his, and he, similarly, had someone, oh, say, his hated father. Why, they would exchange murders; each would murder a total stranger—with no connection. “Like,” Bruno says, “you do my murder and I do yours. For example, your wife, my father. Crisscross.”

Earlier, a close-up of a pair of walking feet had opened the film, much as, twice, a pair of train tracks had crossed one another. Crisscross. Strangers on a Train is, in fact, an extension of Hitchcock’s obsession with doubles in the manner of Shadow of a Doubt, made eight years earlier. In Strangers there are two men on a train, two women at a party, two pairs of detectives, two boys and two old men in two carnival scenes, a pair of crossed tennis rackets on a cigarette lighter—on and on, almost ad infinitum. In a further example, Hitch makes his traditional cameo appearance boarding a train with a double bass, which is as large as he is.

Just as Hitchcock cast handsome, leading-man Joseph Cotton as the villain in Shadow of a Doubt, the director assigned the role of the psychopath Bruno, again against type, to the attractive Walker whose boy-next-door image had been well established in The Clock and Since You Went Away. This is his finest performance.

Just as Hitchcock cast handsome, leading-man Joseph Cotton as the villain in Shadow of a Doubt, the director assigned the role of the psychopath Bruno, again against type, to the attractive Walker whose boy-next-door image had been well established in The Clock and Since You Went Away. This is his finest performance.

Strangers on a Train is, by the way, part of a box set, The Best of Warner Bros. 20-Film Collection: Thrillers, newly released to celebrate the studio’s ninetieth anniversary, running throughout 2013. The films fall between 1931 and 2010 and include The Maltese Falcon, Dirty Harry, The Fugitive, The Shawshank Redemption, L.A. Confidential and Inception. One other Hitchcock film, North by Northwest, is also part of the collection.

Guy doesn’t take Bruno’s murder exchange proposal seriously, thinking it’s as reliable as his theory for legalizing bigamy which Bruno says he will share with him another time. When Guy is leaving the train at Metcalf, Bruno asks boyishly, “Do you think my theory is okay, Guy? You like it?” Guy humors him. “Sure, sure, Bruno. They’re all okay.”

After Guy has left, Bruno picks up the tennis player’s forgotten lighter with the crossed tennis rackets, smiles and says to himself, “Crisscross.”

He was serious, and one night, as part of his half of the presumed agreement, he follows Guy’s wife Miriam (Laura Elliott) to an island carnival. Accompanied by “The Band Played On” from a distant calliope, he strangles her. In one of at least two Hitchcock tours de force in the film, cinematographer Robert Burks uses a large distorting lens to obtain a screen-size image of the killing, reflected in one of the lenses of Miriam’s glasses, which had fallen to the ground. Strangers is the first of twelve films Burks would shoot for Hitchcock.

He was serious, and one night, as part of his half of the presumed agreement, he follows Guy’s wife Miriam (Laura Elliott) to an island carnival. Accompanied by “The Band Played On” from a distant calliope, he strangles her. In one of at least two Hitchcock tours de force in the film, cinematographer Robert Burks uses a large distorting lens to obtain a screen-size image of the killing, reflected in one of the lenses of Miriam’s glasses, which had fallen to the ground. Strangers is the first of twelve films Burks would shoot for Hitchcock.

In several unexpected and clandestine meetings and phone calls, Bruno attempts to persuade Guy to follow through on their “agreement.” Once, Guy pretends to agree and goes to the father’s house one night, even armed with a gun, but when he politely tries to awaken the man—“Mr. Anthony! Don’t be alarmed, but I must talk to you about your son.”—the hand that reaches out to turn on the bed table lamp is Bruno’s.

At a party, the uninvited Bruno, playing the debonair guest, elegantly demonstrates on an elderly woman (Norma Varden) the art of strangulation, one of Hitch’s favorite killing methods. When Bruno sees, across the room, the daughter (Patricia Hitchcock) of a senator (Leo G. Carroll), he is transfixed, breathing heavily, what today would be called a panic attack. The young woman’s face—the glasses, the hair style—reminds him of Miriam. In his catatonic state, he begins strangling the woman in earnest.

At a party, the uninvited Bruno, playing the debonair guest, elegantly demonstrates on an elderly woman (Norma Varden) the art of strangulation, one of Hitch’s favorite killing methods. When Bruno sees, across the room, the daughter (Patricia Hitchcock) of a senator (Leo G. Carroll), he is transfixed, breathing heavily, what today would be called a panic attack. The young woman’s face—the glasses, the hair style—reminds him of Miriam. In his catatonic state, he begins strangling the woman in earnest.

Bruno, continuing to shadow his uncooperative partner, appears at a tennis match where Guy is playing. In another famous moment in the film, while the head-turning crowd follows the back-and-forth movement of the ball, Bruno sits motionless. After Bruno leaves the game to plant the lighter at the fair grounds to incriminate Guy, he accidentally drops it through the grating of a sewer drain.

In the most tense sequence in the film, Hitchcock ingeniously switches back and forth between the tennis match, which Guy must finish as quickly as possible to stop Bruno, and the psychopath who is reaching his arm through the grate for the lighter that rests precariously on a ledge in the gutter. He stretches, he strains, he can almost reach it. Just a little more—— Here Hitchcock, once again, reverses the audience’s sympathies. Just as the viewer in Psycho hopes against normal instinct that Marion’s car will sink in the swamp after Norman (Anthony Perkins) has killed her (Janet Leigh), so here the audience wants Bruno to retrieve the lighter, which he does.

In the most tense sequence in the film, Hitchcock ingeniously switches back and forth between the tennis match, which Guy must finish as quickly as possible to stop Bruno, and the psychopath who is reaching his arm through the grate for the lighter that rests precariously on a ledge in the gutter. He stretches, he strains, he can almost reach it. Just a little more—— Here Hitchcock, once again, reverses the audience’s sympathies. Just as the viewer in Psycho hopes against normal instinct that Marion’s car will sink in the swamp after Norman (Anthony Perkins) has killed her (Janet Leigh), so here the audience wants Bruno to retrieve the lighter, which he does.

The climax of the film is the other Hitchcock tour de force, and one of his most complicated and time-consuming setups—the crash of the carousel. Guy has pursued Bruno to the carnival where Miriam was murdered. They fight on the carousel, almost being thrown off, when the ride dangerously increases in speed and then crashes.

To accomplish this, Hitch photographed a toy merry-go-round exploding from a small charge and then rear-screen projected it, with actors stationed in various positions in front of the screen. As Hitchcock explained, “ . . . the camera lens had to be level and in line with the projector lens. . . . All the shots took nearly half a day to line up for each setup. We had to change the projector every time the angle changed.”

To accomplish this, Hitch photographed a toy merry-go-round exploding from a small charge and then rear-screen projected it, with actors stationed in various positions in front of the screen. As Hitchcock explained, “ . . . the camera lens had to be level and in line with the projector lens. . . . All the shots took nearly half a day to line up for each setup. We had to change the projector every time the angle changed.”

Partially buried under the debris of the wrecked carousel, Bruno denies that he has the lighter. “It’s still on the island where you left it,” he tells Guy. As he is dying, his hand relaxes and reveals the lighter in his palm.

In almost too quick an ending—after all, Hitch’s tricks and slights of hand are over—Guy and the other woman in his life, Ann (Ruth Roman), are seated on yet another train when a minister nearby says, “I beg your pardon, but aren’t you Guy Haines?” Guy and Ann exchange looks and quickly move away.

In the course of the film, it is apparent that Guy himself isn’t entirely innocent—most obviously he has committed murder through his words. While relaying to Ann on the telephone that Mariam still refuses to give him a divorce, he remarks, “I said I’d like to break her foul, poisonous, useless little neck!” And then, over the rumbling of a passing train, he shouts, “I said I could strangle her!” In the visit to the bedroom of Bruno’s father, Hitchcock’s ambiguous lighting and composer Dimitri Tiomkin’s emphasis-shifting music suggest that Guy just might kill the man after all.

Too, there is the inference of a homosexual courtship between Bruno and Guy, that Bruno is the dark side of the passive Guy in this “partnership.” Bruno is the one who acts, who does what Guy perhaps would like to accomplish, although quite the opposite of what Bruno says at their first meeting: “I certainly admire people who do things,” and “I never seem to do anything.” Hitchcock and Czenzi Ormonde’s script—Raymond Chandler’s submitted draft was unsatisfactory—had to be careful with any effeminate dialogue and hand gestures that might anger the Hays Office.

Too, there is the inference of a homosexual courtship between Bruno and Guy, that Bruno is the dark side of the passive Guy in this “partnership.” Bruno is the one who acts, who does what Guy perhaps would like to accomplish, although quite the opposite of what Bruno says at their first meeting: “I certainly admire people who do things,” and “I never seem to do anything.” Hitchcock and Czenzi Ormonde’s script—Raymond Chandler’s submitted draft was unsatisfactory—had to be careful with any effeminate dialogue and hand gestures that might anger the Hays Office.

Perhaps not the best of the four scores Tiomkin wrote for Hitch—that honor probably goes to the more lyrical and subtle I Confess, Hitch’s next picture—the one for Strangers is clearly the most typical of the composer, with rhythmic variety, clean sonorities and that always overt Russian flavor.

The main title music introduces the two main themes for the two protagonists—for Guy a gentle solo violin tune and for Bruno the brittle etching of high violin harmonics and disturbing tone clusters. Conceivably, since both melodies focus on the strings, this was Tiomkin’s way, certainly urged on him by Hitch, of suggesting the link between these two men, their similarities and that, perhaps, they are more than just companions on a nightmare journey. The two themes especially come to the fore, and are imaginatively varied, during the tennis game/lighter retrieval sequence.

The rhythmic, rising-and-falling motif that accompanies the pair of shoes across the station platform in the film’s beginning never appears again, which is unfortunate. Catchier, and more memorable, than either of the two other themes, the motif could just as easily accompany stalking gunfighters in one of Tiomkin’s many Western scores.

The other two scores Tiomkin wrote for Hitch are Shadow of a Doubt, in which the director insisted on using Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow waltz as the idée fixe for the villain, and Dial M for Murder, in which Tiomkin, presumably on his own, lifted some of the coronation music from Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov when Ray Milland dials the telephone, the setup for Grace Kelly’s intended murder.

The other two scores Tiomkin wrote for Hitch are Shadow of a Doubt, in which the director insisted on using Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow waltz as the idée fixe for the villain, and Dial M for Murder, in which Tiomkin, presumably on his own, lifted some of the coronation music from Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov when Ray Milland dials the telephone, the setup for Grace Kelly’s intended murder.

Always specific and discerning in the use of music, both source and in the score, Hitch wanted to add atmosphere—sure, but also to heighten the incongruity of light music as a backdrop to those dark deeds at the carnival, and wanted Tiomkin to incorporate such traditional and disarming songs as “Carolina in the Morning,” “Ain’t She Sweet” and “Oh! You Beautiful Doll.”

The delightful actress Marion Lorne plays Bruno’s mother, she as batty as her son. In the film’s funniest moment, after she has given him a manicure, she invites him to view her new painting. It is an ugly, surrealistic portrait of what could be an Usher family member out of Edgar Allan Poe. After unrestrained laughter, Bruno says, “You’re wonderful, Ma! It’s the old boy, all right. That’s father!” Tiomkin’s orchestra shrieks a series of dissonant, grating chords, symbolic of the composer’s modernistic bent, as compared with, say, Steiner or Waxman, a noise which surely delighted the fun-loving Tiomkin.

“Is it [your father]?” she asks, puzzled. “I was trying to paint Saint Francis.”

Fabulous review. I could go on about this film all day – I love it that much. Like you said, it truly was one of Hitchcock’s best.

I consider Robert Walker’s performance not only the best of his career, but one of the best in Hollywood cinema, period.