“Do you think because I’m poor and obscure and plain that I’m soulless and heartless? I have as much soul as you and fully as much heart.”—— Jane to Mr. Rochester

“Do you think because I’m poor and obscure and plain that I’m soulless and heartless? I have as much soul as you and fully as much heart.”—— Jane to Mr. Rochester

In the 1943 version of Jane Eyre, [intlink id=”259″ type=”category”]Joan Fontaine[/intlink] is playing yet another variation on her role of the new Mrs. de Winter in Rebecca, that of a demure woman with apparently little or no allure. “Mousy” might be the word. To some degree, in another Alfred Hitchcock film, Suspicion, she would have a similar part as a naïve woman growing more and more fearful that her husband might be planning to murder her. In both Jane Eyre and Rebecca, each women is haunted by a previous wife, one quite insane and alive, one dead.

Much like the nameless heroine in Rebecca, in Jane Eyre a second heroine and survivor against harsh odds, Jane comes to live in another mysterious old house in the English countryside, not as a new wife but at first as a governess. The secrets of the Cornish Manderley in Rebecca are replaced by those of a much more terrifying place, Thornfield Hall in Yorkshire. In the end, both houses suffer a conflagration, for the first a ritual cleansing, for the second a tender resolution. At Manderley, a dead wife holds a strange control over the living—worshipful for housekeeper Mrs. Danvers and suffocating for the master Maxim de Winter; at Thornfield, the wife is very much alive, at first unknown to Jane, and hidden away in a tower room, for good reason.

Jane Eyre is a dark film, darkly photographed by George Barnes (Meet John Doe, Rebecca, War of the Worlds [1953]), broodingly directed by Robert Stevenson and presided over, in ways not even now thoroughly understood, by what Fontaine called “such a big man in every way that no one could stand up to him.” [intlink id=”150″ type=”category”]Orson Welles[/intlink]. “On the first day,” she wrote in her autobiography No Bed of Roses, “at four o’clock”—having been many hours late—“he strode in followed by his agent, his secretary, his valet and a whole entourage. Approaching us, he proclaimed, ‘All right, everybody, turn to page eight.’ And we did it, though he was not the director.”

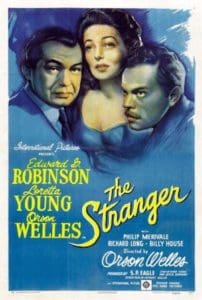

The screen-credited director, Englishman Stevenson, is best known for his Walt Disney films (Kidnapped, Son of Flubber, Mary Poppins) and the mogul’s TV series Wonderful World of Color. It has been said that in Jane Eyre Stevenson was able to avoid any directorial influences from the omnipresent Welles. But simply observing the screen, with its myriad shadows, deep focus images and the oppressive mood, as in The Stranger, which Welles did direct, it’s easy to doubt that Stevenson’s screen escaped untouched by Welles.

The screen-credited director, Englishman Stevenson, is best known for his Walt Disney films (Kidnapped, Son of Flubber, Mary Poppins) and the mogul’s TV series Wonderful World of Color. It has been said that in Jane Eyre Stevenson was able to avoid any directorial influences from the omnipresent Welles. But simply observing the screen, with its myriad shadows, deep focus images and the oppressive mood, as in The Stranger, which Welles did direct, it’s easy to doubt that Stevenson’s screen escaped untouched by Welles.

It is well known that Welles’ control was seriously restricted in another film of similar milieu, The Third Man, set a hundred years later. That director, Carol Reed, though clearly impressed by Orson, was a strong enough personality to maintain respectable control, even against an even stronger personality. Seen in retrospect, however, that film could easily be a teaching example of the Wellesian technique. Coincidence?

Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel, published under the pseudonym of Currer Bell, is in the style of the Gothic novel popular in England at the time. The youngest of the three Brontë sisters, she followed in the footsteps of other women novelists such as Elizabeth Gaskell and Fanny Burney who wrote about young ladies’ introduction to the cruel, male-dominated world of the Industrial Revolution. (Jane Austen, of an earlier generation and more a novelist of social manners, had died the year after Charlotte’s birth.) Young feminine hearts desired domination by a larger-than-life man—handsome, mysterious, even aloof, a man ready to introduce them to his new world. The basic ideas, allowing for women’s liberation, would persist in the romance novels of today.

But before any more introduction, the movie plot of Jane Eyre, should it be unknown to any one: Immediately establishing the gloom of the film, Jane Eyre (Peggy Ann Garner) is an independent and defiant orphan living at Gateshead Hall with her aunt, Mrs. Reed (Agnes Moorehead), and her spiteful son (Ronald Harris). Mrs. Reed finds Jane’s behavior untenable and arranges for her to be sent to an orphanage. As Jane is leaving for Lowood, the one kind person in the household, the maid Bessie (Sara Allgood), sees her to the door and gives her a token of remembrance.

But before any more introduction, the movie plot of Jane Eyre, should it be unknown to any one: Immediately establishing the gloom of the film, Jane Eyre (Peggy Ann Garner) is an independent and defiant orphan living at Gateshead Hall with her aunt, Mrs. Reed (Agnes Moorehead), and her spiteful son (Ronald Harris). Mrs. Reed finds Jane’s behavior untenable and arranges for her to be sent to an orphanage. As Jane is leaving for Lowood, the one kind person in the household, the maid Bessie (Sara Allgood), sees her to the door and gives her a token of remembrance.

For the coach ride to Lowood, composer Bernard Herrmann writes some exciting music, more inventive than a mere “galloping” rhythm, with ever-changing instrumentation. When the coachman (Charles Coleman) asks Jane where she is going and receives the answer, his silence and vacant look are telling. The distant shot of the coach, stopping at the gate of Jane’s new home and small beside the vast mountains in the distance, recalls Renfield’s arrival at the count’s castle in the 1931 scoreless version of Dracula. In Jane Eyre, in 1943, some dark, portentous music adds flavor to the setting and hints at Jane’s future.

Sounding like a name out of Charles Dickens, the man who runs Lowood is Henry Brocklehurst (Henry Daniell), an evil minister who abuses the children in his care. As there was kind Bessie at the Reed’s house, so at the orphanage there is the delicate Helen (the already lovely eleven-year-old Elizabeth Taylor, only a year from National Velvet). In defiance of Brocklehurst’s isolation of Jane, who has to stand, alone, on a stool “for the rest of the day” in a vast, empty room, Helen brings a piece of bread.

Sounding like a name out of Charles Dickens, the man who runs Lowood is Henry Brocklehurst (Henry Daniell), an evil minister who abuses the children in his care. As there was kind Bessie at the Reed’s house, so at the orphanage there is the delicate Helen (the already lovely eleven-year-old Elizabeth Taylor, only a year from National Velvet). In defiance of Brocklehurst’s isolation of Jane, who has to stand, alone, on a stool “for the rest of the day” in a vast, empty room, Helen brings a piece of bread.

Jane is also fortunate in the benevolent intercession of Dr. Rivers (John Sutton), who rescues her from another Brocklehurst punishment, walking in a circle in the rain carrying aloft two flatirons.

After Helen has died, Jane, now grown into a young woman (Fontaine), leaves the school for Thornfield Hall. She has been hired as governess to a little French girl, Adele (Margaret O’Brien), ward of a Mr. Edward Rochester (Welles). The housekeeper, Mrs. Fairfax (Edith Barrett), while showing Jane to her room, announces that the master of the house has been away sometime, and that his visits are always “unexpected and sudden.”

Later, as Jane is walking about the moors, out of the fog emerges a horseman and his Great Dane, almost running her down and throwing the rider to the ground—all supported by some arresting music from Herrmann. Without identifying himself, the man, wearing a great cloak, exchanges a few words, then remounts his animal and disappears in the fog, the large dog following behind. That evening, Jane discovers that the man on the moor, now sitting by the fire and at first hidden by a deep wing of the chair, is Mr. Rochester.

Later, as Jane is walking about the moors, out of the fog emerges a horseman and his Great Dane, almost running her down and throwing the rider to the ground—all supported by some arresting music from Herrmann. Without identifying himself, the man, wearing a great cloak, exchanges a few words, then remounts his animal and disappears in the fog, the large dog following behind. That evening, Jane discovers that the man on the moor, now sitting by the fire and at first hidden by a deep wing of the chair, is Mr. Rochester.

Jane quickly settles into the routine of the household, feeling affection for Adele and a growing closeness toward Mr. Rochester, despite his morose temperament. One night, Jane hears peculiar laughter and finds Mr. Rochester’s bed curtains on fire. The next day he leaves and is gone for many months.

When he does return, he heads a procession of coaches bringing guests for a wedding the next day—the master of the house to Blanche Ingram (Hillary Brooke). When Mr. Rochester accuses Blanche of planning to marry him for his wealth, she is indignant and leaves, whereupon he confesses to Jane that it is she he wants to marry. Jane gladly accepts his proposal.

When he does return, he heads a procession of coaches bringing guests for a wedding the next day—the master of the house to Blanche Ingram (Hillary Brooke). When Mr. Rochester accuses Blanche of planning to marry him for his wealth, she is indignant and leaves, whereupon he confesses to Jane that it is she he wants to marry. Jane gladly accepts his proposal.

But in the midst of the ceremony, an attorney (Erskine Stanford) announces that Mr. Rochester already has a wife named Bertha. When her elder brother (John Abbott) confirms this, Mr. Rochester stops the proceedings and shows the wedding party his spouse, locked away, insane, in the tower, watched over by Grace Poole (Edith Griffies). Distraught and heartbroken, Jane leaves Mr. Rochester and Thornfield.

Returning to Gateshead, she is blissfully reunited with Bessie, who at first fails to recognize the young woman who enters her kitchen. Jane finds Mrs. Reed ill and her son dead, having committed suicide. After Mrs. Reed dies, Jane hears a voice—Mr. Rochester calling to her. (A more logical literary device would be for Mrs. Fairfax to write her of the situation, but this was, remember, the mid-nineteenth century.) Returning to Thornfield, Jane discovers a wing of the house in ruins; Bertha had started a fire before jumping to her death. Mr. Rochester, in trying to rescue his wife, was blinded by the flames. Now Jane marries him and by the time their child is born, his eyesight has returned.

Returning to Gateshead, she is blissfully reunited with Bessie, who at first fails to recognize the young woman who enters her kitchen. Jane finds Mrs. Reed ill and her son dead, having committed suicide. After Mrs. Reed dies, Jane hears a voice—Mr. Rochester calling to her. (A more logical literary device would be for Mrs. Fairfax to write her of the situation, but this was, remember, the mid-nineteenth century.) Returning to Thornfield, Jane discovers a wing of the house in ruins; Bertha had started a fire before jumping to her death. Mr. Rochester, in trying to rescue his wife, was blinded by the flames. Now Jane marries him and by the time their child is born, his eyesight has returned.

Surprisingly faithful to the book as novel-to-movie adaptations go, nevertheless much had to be omitted or abridged. Jane does not, for example, arrive at Thornfield until Chapter XI, meaning a substantial portion of her life at Gateshead and Lowood was eliminated from the film. Although there are at least four deaths of named characters in the movie, there were more in the novel.

Orson Welles was familiar with Charlotte Brontë’s novel and had played Mr. Rochester in a Mercury Theatre on the Air radio program in September of 1938, a month before his famous, panic-causing War of the Worlds broadcast. His film version of Mr. Rochester is cast in much the same manner—flamboyant, theatrical, almost musical. Not in finely nuanced details but in large swaths of melodrama and pathos, as if, indeed, he were acting on radio, or, even more typical of histrionic projection, on stage.

As Maxim de Winter in Rebecca, Laurence Olivier renders a somewhat subdued version of Mr. Rochester in a much similar style. Even if the brooding remains, he is a bit more extroverted as Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights opposite Merle Oberon.

As Maxim de Winter in Rebecca, Laurence Olivier renders a somewhat subdued version of Mr. Rochester in a much similar style. Even if the brooding remains, he is a bit more extroverted as Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights opposite Merle Oberon.

Welles’ performance in Jane Eyre, though commanding (scene-stealing) and impressive (showy), borders on the surreal vis-à-vis Fontaine’s warm, sincere and understated acting, as so often with her. This contrast is uncannily described, albeit in reference to the novel characters, by Walter Allen in his literary study The English Novel: “ . . . the dialogues between [Rochester] and Jane are absurd, but they are absurd only on his side, because he is a figment of Charlotte Brontë’s imagination, a dream figure, whereas the author herself, or her projection of herself in Jane, is wholly real.”

The production values of Jane Eyre, as always with Darryl F. Zanuck, are first-class, and parallels in mood can be seen in other such darkly photographed, gloomy films from 20th Century-Fox around this time—The Black Rose, The Lodger, Hangover Square and Dragonwyck.

When the film was first released, the three child stars received high praise, especially Garner as the young Jane Eyre. Margaret O’Brien, who received a miniature Oscar as “Outstanding Child Actress” for Meet Me in St. Louis, was unfortunately among the many child stars who failed to mature into adult roles and she went into television in the early 1950s. Famous for being able to cry on cue, she once asked a director how he wanted the tears, all the way down her cheek or only half way. And Elizabeth Taylor’s much-publicized life is well known. Before her notoriety had begun, when Welles encountered her on the Jane Eyre set, he is rumored to have said, “Remind me to be around when she grows up.”

When the film was first released, the three child stars received high praise, especially Garner as the young Jane Eyre. Margaret O’Brien, who received a miniature Oscar as “Outstanding Child Actress” for Meet Me in St. Louis, was unfortunately among the many child stars who failed to mature into adult roles and she went into television in the early 1950s. Famous for being able to cry on cue, she once asked a director how he wanted the tears, all the way down her cheek or only half way. And Elizabeth Taylor’s much-publicized life is well known. Before her notoriety had begun, when Welles encountered her on the Jane Eyre set, he is rumored to have said, “Remind me to be around when she grows up.”

Certainly among the high production values is Bernard Herrmann’s presence, the first of his many scores for the studio, and one of his most conventional—not in the sounds heard, which, as always, are pure Herrmann, but in the use of a standard, large twentieth-century orchestra. The composer employs an “unconventional” orchestral makeup in the exclusion of strings in Journey to the Center of the Earth, the use of only strings in Psycho and numerous electronic instruments and sans woodwinds in The Day the Earth Stood Still. Of course, as always, Herrmann orchestrated his own music.

A highly romantic score, then, one built out of leitmotifs and variations, with melodies for the two main characters, as well as the expected love theme. Some of the themes are related, as, for example, the love theme contains four notes from Mr. Rochester’s theme. Jane’s theme, first heard at the end of the main title on the oboe, experiences a “growing” dimension during the story, from the young waif at Lowood to the mature woman falling in love at Thornfield. In these terms, the score is even “old-fashioned” by the composer’s standards. The love theme, for example, is one of Herrmann’s longest; later he would, more and more, build his musical architecture around brief motifs, cells that would be the crux of an entire score, best exemplified in Journey to the Center of the Earth.

A highly romantic score, then, one built out of leitmotifs and variations, with melodies for the two main characters, as well as the expected love theme. Some of the themes are related, as, for example, the love theme contains four notes from Mr. Rochester’s theme. Jane’s theme, first heard at the end of the main title on the oboe, experiences a “growing” dimension during the story, from the young waif at Lowood to the mature woman falling in love at Thornfield. In these terms, the score is even “old-fashioned” by the composer’s standards. The love theme, for example, is one of Herrmann’s longest; later he would, more and more, build his musical architecture around brief motifs, cells that would be the crux of an entire score, best exemplified in Journey to the Center of the Earth.

Working on Jane Eyre was the beginning of Herrmann’s fascination with the world of the Brontës, and even inspired a permanent move to England in 1971. At least two themes from Jane Eyre would reappear in his opera Wuthering Heights, which, in turn, would seep into a few passages of another film score, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, also set in England.

Jane Eyre contains some of those familiar supporting players who were exchanged, back and forth, among the various studios, particularly during World War II when parts were hard to fill. Some of the actors not previously mentioned, and mostly in minuscule parts, include Barbara Everest (Gaslight), Alec Craig (Abe Lincoln in Illinois), Mary Forbes (Captain Blood), Frederick Worlock (the Universal Sherlock Holmes), Brandon Hurst (Stanley and Livingstone), Mae Marsh (a John Ford favorite), Ivan Simpson (The Adventures of Robin Hood), Aubrey Mather (Heaven Can Wait) and Barry Macollum (Beau Geste). Unfortunately, these mostly British performers rarely received screen credit.

The exchange of supporting players being what it was at the time, a number of the Jane Eyre actors—Billy Bevan, Yorke Sherwood, Ethel Griffies and John Meredith—would reappear in another Brontë-related film, supposedly about the lives of the three sisters. In filming Devotion, Warner Bros. wanted Fontaine to play Emily opposite her real sister Olivia de Havilland as Charlotte (Nancy Coleman would play third sister Anne), but negotiations failed and Ida Lupino received the part. The idea of Joan and Olivia appearing in the same movie is dubious, as they had not been on speaking terms since the early 1940s.

The exchange of supporting players being what it was at the time, a number of the Jane Eyre actors—Billy Bevan, Yorke Sherwood, Ethel Griffies and John Meredith—would reappear in another Brontë-related film, supposedly about the lives of the three sisters. In filming Devotion, Warner Bros. wanted Fontaine to play Emily opposite her real sister Olivia de Havilland as Charlotte (Nancy Coleman would play third sister Anne), but negotiations failed and Ida Lupino received the part. The idea of Joan and Olivia appearing in the same movie is dubious, as they had not been on speaking terms since the early 1940s.

Devotion was made in 1943 but not released until 1946, for obvious reasons. It is a weak film, hardly in a class with Jane Eyre. Paul Henreid as the made-up, shared love interest between Emily and Charlotte is awkwardly miscast, the plotting is ponderous and the facts are a jumble of inaccuracies and exaggerations. The only saving grace, and the only reason to “hear” the film, is Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s imaginative score, which captures the Yorkshire moors and that horseman of death as perhaps the acting and photography, Ernest Haller notwithstanding, cannot.

Excellent review/recap! This movie caught my attention when i was just in my 20s, how strangely booming Welles’ Rochester came across, otherworldy almost, to the multitude of quirky and reserved characters that abound in Bronte’s world. Like many, i found it difficult to see Fontaine as the unattractive, maybe more mousey Jane — she isn’t any Ava but her smooth, subtle beauty had to be contained somewhat… I agree that there are many seemingly shots and scenes that carry an Ambersonian- and Stranger-esque twist with shadows and closeups; i think if we traverse most of WElles’ catalogue of actor-for-hire work, a number of directors either took the opportunity to reflect some of his influence or just allowed him some booming input in how to frame a scene.

This is a haunting classic, where Welles and Hermann truly dominate. WEll done!

Thanks for this detailed commentary on the 1944 JANE EYRE, and especially for the comments on Bernard Herrmann’s score, which for me is the most outstanding element of the movie–I’ve listened to the score on CD again and again! Orson Welles remains my favorite Rochester among the many screen Rochesters, because I can believe his Rochester is a bit mad himself. I would like to add a word for Joan Fontaine, who, of all actresses I’ve seen in the role of Jane Eyre, most resembles the author of the novel, Charlotte Bronte. Fontaine’s “understated” acting in the role has always given me the impression that this Jane has learned to act subdued, but her interest in the slightly mad Rochester is telling!

I enjoyed reading your comments.

Enterprises having a large website with a lot of traffic influx will require the reseller hosting package.

They offer so many extras that make starting up a new website so simple that even a complete

novice could get a website up and running. The laws have been changing and many portals that offer services

are finding it harder and harder to get their word out there.

I enjoyed completely! But, what happened to little Adele at the end of the movie? Dont recall her mentioned after the fire.

Joan Fontaine plays Jane Eyre to perfection. She’s quiet, she’s victorian, she’s English. Her love for Rochester can be seen to grow; and when she thinks she must leave him, the emotion is forced up through her reserved victorian straight jacket and is excellently performed. Wells is good as Rochester, though somewhat Johnny One Note. Had the movie shown the entire novel, Jane’s fleeing Thornfield, meeting the Rivers family and then reunited with Rochester, he may have had more opportunity to develop his character.