“I guess if the earth were made of gold, men would die for a handful of dirt.”—— Hooker (Gary Cooper), the closing line of the film

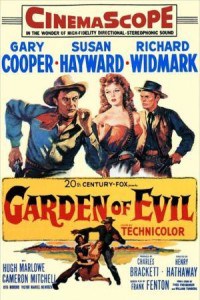

The Garden of Evil that 20th Century-Fox made in 1954, one of the early CinemaScope films released to lure the growing TV audiences back to the theaters, recalls a number of earlier and later films of the same type. The theme of greed is stolen most obviously, though far less imaginatively, from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, made seven years earlier. As to the time-tested rescue-someone-in-distress plot in Garden of Evil, from among many examples The Professionals of 1966 comes to mind as also a better picture. Even Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil has a similar title, though a totally different theme.

Filmed on location in central Mexico with gray mountain vistas to underpin the austere theme, the film had highly qualified artists involved that could have made something of note. It is directed by [intlink id=”7″ type=”category”]Henry Hathaway[/intlink], photographed by Milton Krasner, art direction by Lyle Wheeler and Edward Fitzgerald, edited by James B. Clark and scored by Bernard Herrmann. First in line for the failings of the film is Charles Brackett (along with Saul Wurtzel), usually a reliable producer, but here experiencing an off day. The usual producer, the astute Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck would have probably seen the pitfalls and nixed the entire project. Was he out of town? Otherwise occupied on a casting couch with a starlet? Why his name is absent from the screen credits isn’t clear.

But the central weakness of the film lies at the feet—more accurately in the pens and creative minds—of the three screenwriters. More about that later.

Just remember The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and the plot is basically there—instead of three greedy men after gold, there are four: Hooker ([intlink id=”215″ type=”category”]Gary Cooper[/intlink]), the easygoing ex-sheriff, the moral one who does much of the thinking for the group; Fiske ([intlink id=”155″ type=”category”]Richard Widmark[/intlink]), the watchful observer of things, the most enigmatic of the bunch who will prove the hero in his way; Luke Daly (Cameron Mitchell), the blustery tough guy who is actually the weakest of the band; and Vicente Madariaga (Mexican actor Victor Manuel Mendoza), the local drifter, the first to volunteer for the trek—and for the money.

Now add to the plot of Garden of Evil a woman, Leah Fuller ([intlink id=”278″ type=”category”]Susan Hayward[/intlink]). She provides not only the essential element of the rescue theme but also introduces romance, however tepid. She hires the men to accompany her through Indian country to rescue her husband John (Hugh Marlowe), injured in a gold mine accident. The three Americans, each in his own way, whether through physical assault or aloof scrutiny, are interested in her. She, by contrast, is distant and wary.

In the opening image on screen, the three American men come ashore off the eastern coast of Mexico. En route to the gold fields of California, they have been stranded by a disabled steamer and decide to imbibe at a local cantina. They are approached by Leah, who offers them each $2,000 to rescue her husband. Seduced by immediate money versus the delayed uncertainty of finding gold in faraway California, the five men, including Vicente, set out.

In the opening image on screen, the three American men come ashore off the eastern coast of Mexico. En route to the gold fields of California, they have been stranded by a disabled steamer and decide to imbibe at a local cantina. They are approached by Leah, who offers them each $2,000 to rescue her husband. Seduced by immediate money versus the delayed uncertainty of finding gold in faraway California, the five men, including Vicente, set out.

The over-all scenario is so simple, the subplot of romance so devoid of nuance, that it requires little space to describe, even by this writer. The first forty-five minutes of the film consist of alternate scenes of the travelers either trekking through mountain landscapes or stopping to camp, which requires sessions of humdrum dialogue. Hooker and Fiske have a conversation of little consequence, Hooker and Leah have a tepid one and so on.

During these forty-five minutes, there is one action scene. Luke assaults Leah, but she is able to repel him. On the rebound and angry, Luke challenges Hooker, who quickly proves Luke’s cowardice. After their fight, Luke falling twice into the campfire and being humiliated enough to cry, Hooker comforts him with words of encouragement and his own moistened bandanna for the loser’s battered face. This all suggests that Hooker might well be the one “good guy” among these greedy soldiers of fortune, the one most likely to survive—plot and movie.

Vicente is marking the trail—a machete hack to a tree, stone arrows on the ground and branches forming signposts—but Hooker and Fiske have noticed. “You think,” Hooker asks, “he might wanna make this trip again?” Fiske replies, “He just might wanna get back from this one.” Leah notices Vicente’s action as well and follows behind him, destroying his markers.

Vicente is marking the trail—a machete hack to a tree, stone arrows on the ground and branches forming signposts—but Hooker and Fiske have noticed. “You think,” Hooker asks, “he might wanna make this trip again?” Fiske replies, “He just might wanna get back from this one.” Leah notices Vicente’s action as well and follows behind him, destroying his markers.

Eventually—it’s really not as long as it may seem to the audience—the five riders reach the so-called Garden of Evil, considered the haunt of malevolent spirits by the local Apaches (usually referred to here as “Indians”), and find John Fuller half buried in the mine cave-in. Freed but bed-ridden with a broken leg, he is ministered to by Hooker who fashions a splint and benevolently suggests he be given coffee and hot soup, compassion that never seemed to occur to the others.

Hooker goes for a walk—lovely mountain vistas—and finds an Indian feather and sees a smoke signal in the distance. He warns the party and they make a dash for it that night. Pursued by the Indians, they still stop to make camp. John, who has been belittling his wife, saying she is using the men to her advantage, does an heroic about-face. With Luke’s help, he mounts a horse and dashes off to create a diversion.

Hooker goes for a walk—lovely mountain vistas—and finds an Indian feather and sees a smoke signal in the distance. He warns the party and they make a dash for it that night. Pursued by the Indians, they still stop to make camp. John, who has been belittling his wife, saying she is using the men to her advantage, does an heroic about-face. With Luke’s help, he mounts a horse and dashes off to create a diversion.

Luke is the first to die from Indian arrows, then John, found hanging upside-down. Vicente is next, standing up defiantly, in the best tradition of “Come on, you guys! Kill me!”—all in Spanish of course—before he is brought down by yet another arrow. The three survivors cross the hills and backtrack to the trail along the edge of a canyon precipice. Hooker and Fiske draw cards to see who will stay behind to hold off the Indians; the other will accompany Leah in a race for safety. Fiske is to stay.

When Hooker and Leah are safe on another mountain ridge, he says he must go back, that somehow Fiske had cheated at the cards. Hooker shoots the last two Indians on the way back and finds that Fiske, now critically wounded, had killed the rest. As Fiske is dying, he encourages his partner to settle down with Leah. Hooker returns to Leah and the two . . . well, yes: they ride off together, their mounted figures distant specks in the last of the film’s vast landscapes, the sun setting.

When Hooker and Leah are safe on another mountain ridge, he says he must go back, that somehow Fiske had cheated at the cards. Hooker shoots the last two Indians on the way back and finds that Fiske, now critically wounded, had killed the rest. As Fiske is dying, he encourages his partner to settle down with Leah. Hooker returns to Leah and the two . . . well, yes: they ride off together, their mounted figures distant specks in the last of the film’s vast landscapes, the sun setting.

As Fiske had said, with every sunset someone dies, and with this sunset it is his turn.

The acting is uniformly inconsistent, never really arresting. This is an adventure yarn, and it’s presumed that, early on, it was decided acting would be secondary. Cooper is subdued even for Cooper. He made a better movie, Vera Cruz, also released in 1954, also filmed in Mexico, also set in the mid-nineteenth century and also about greed—the stealing of gold. Cooper was better in Vera Cruz because, for one reason, he had a strong, clearly defined nemesis in Burt Lancaster.

Hayward is strangely unengaging. Note her deadpan speech to Cooper about her husband and the volcanic ash burying all but the church steeple and mine shaft. Even her indifference toward the men is without nuance, little charisma toward Cooper whom she is supposed to love. Perhaps, with the trekking and the landscape interests, there was little time to develop romantic fireworks.

Hayward is strangely unengaging. Note her deadpan speech to Cooper about her husband and the volcanic ash burying all but the church steeple and mine shaft. Even her indifference toward the men is without nuance, little charisma toward Cooper whom she is supposed to love. Perhaps, with the trekking and the landscape interests, there was little time to develop romantic fireworks.

Widmark is reliable as always, credibly drawing for his apathetic character that fine line between moments of fervent commitment and those of distant detachment. Mitchell seems to alternate between poor delivery and flagrant overacting. Hugh Marlowe is—well, Hugh Marlowe, seemingly unemotional when he’s supposed to be emotional, and, as always, hampered by that impassive face.

Rita Moreno appears briefly in the early cantina scene when she sings two songs, one, “Aqui,” written by Ken Darby and Lionel Newman.

The scenery is one of the few pluses of Garden of Evil, though beside the panoramas in a John Ford Western, the cinematography does pale somewhat. In only the second year of its use, the new CinemaScope lens is confidently handled by Krasner, who captures the varied Mexican landscapes in slightly desaturated tones. Filling the added width of the screen is a new problem to be solved, and it’s hard to avoid lining up the five actors in a row; other times two stars may be positioned on each side of the screen, which looks posed and uncinematic. Especially impressive is the matte shots of the horsemen riding the edge of that deep crevasse, first to and then from the mine shaft.

The scenery is one of the few pluses of Garden of Evil, though beside the panoramas in a John Ford Western, the cinematography does pale somewhat. In only the second year of its use, the new CinemaScope lens is confidently handled by Krasner, who captures the varied Mexican landscapes in slightly desaturated tones. Filling the added width of the screen is a new problem to be solved, and it’s hard to avoid lining up the five actors in a row; other times two stars may be positioned on each side of the screen, which looks posed and uncinematic. Especially impressive is the matte shots of the horsemen riding the edge of that deep crevasse, first to and then from the mine shaft.

Much of whatever is deficient in the acting must be blamed on the three screenwriters, Frank Fenton, William Tunberg and author of the story Fred Freiberger. The actors have to speak some pretty banal lines. Marlowe’s tirades against his wife are surprisingly empty and unconvincing, partly the actor’s fault. And notice how many questions the characters ask one another—an easy writer’s crutch but how clichéd, and boring.

There are some glaring contradictions and unrealistic situations. At the first rest stop along the journey, while relaxing under the trees and observing Leah feed her horse, Fiske asks Hooker how far it is to where they’re going. Presumably having never been there—Leah is their guide—Hooker replies, “Several days.” Later, in another pause along the trail when Leah describes the volcanic eruption, Hooker asks her how much further! Why, when hotly pursued by the Indians, does the group twice stop to make camp? Even Luke, the not-too-bright one, saw this idiocy and once lashed out at Hooker, saying they were already in a “dead run” from their pursuers. Speaking of the ever-present Indians, why do the men, especially Hooker, walk around on mountain ridges and otherwise make themselves conspicuous?

There are some glaring contradictions and unrealistic situations. At the first rest stop along the journey, while relaxing under the trees and observing Leah feed her horse, Fiske asks Hooker how far it is to where they’re going. Presumably having never been there—Leah is their guide—Hooker replies, “Several days.” Later, in another pause along the trail when Leah describes the volcanic eruption, Hooker asks her how much further! Why, when hotly pursued by the Indians, does the group twice stop to make camp? Even Luke, the not-too-bright one, saw this idiocy and once lashed out at Hooker, saying they were already in a “dead run” from their pursuers. Speaking of the ever-present Indians, why do the men, especially Hooker, walk around on mountain ridges and otherwise make themselves conspicuous?

A bit more attention, screenwriters, to your script! Also this: While Hooker and Fiske are cutting cards to settle who stays behind to repel the Indians, Leah asks if both of them have gone crazy, and then turns to one and says, “And you, too?”

The theme of the film is greed, but we don’t sense the characters’ greed, not the vivid way it’s realized in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, since that film is the archetype—in the philosophical understanding of Howard (Walter Huston), in the somewhat hidden avarice of Curtin (Tim Holt) and in the rabid insanity of Dobbs (Humphrey Bogart). In Garden of Evil, Bernard Herrmann’s music conveys greed far better.

The theme of the film is greed, but we don’t sense the characters’ greed, not the vivid way it’s realized in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, since that film is the archetype—in the philosophical understanding of Howard (Walter Huston), in the somewhat hidden avarice of Curtin (Tim Holt) and in the rabid insanity of Dobbs (Humphrey Bogart). In Garden of Evil, Bernard Herrmann’s music conveys greed far better.

In the highly recommended biography of the composer, A Heart at Fire’s Center, its author Steven C. Smith renders an accurate verdict on the film itself as “undistinguished,” “tedious and uninvolving” and “a leaden rehash of Warner Brothers’ Treasure of the Sierra Madre . . . ” Herrmann never had any interaction with director Hathaway regarding the music, and Smith writes, “It was another film Herrmann would not have undertaken had the CBS Symphony survived radio’s demise; but it was an opportunity to work in a genre new to Herrmann’s film career: the Western.” Garden of Evil is always called the composer’s only Western, though his score for The Kentuckian, released the following year, has something of a Western flavor, albeit the “West” of the U.S. frontier in the 1820s, in a journey from Kentucky to Texas.

Few people would believe that Herrmann’s Garden of Evil score, isolated from the screen, say, in a soundtrack album, belongs to a film in the Western genre. Even with the screen it never sounds like a Western, certainly not in the Dimitri Tiomkin and Elmer Bernstein sense; it has none of that vitality, that exuberance and only rarely conveys those wide, open spaces. The most Western-like passages occur during the trekking, with mountains in the distance or forests in the foreground. One beautiful example occurs after the group has reached the mine and Hooker walks through the landscape—until he finds that feather, then the orchestral palette, begun in souring woodwinds, then in distraught timpani, does an about-face and is once again pure Herrmann.

Most of the time, as in the very beginning of the journey when the little caravan reaches a chasm and passes through a valley, Herrmann’s orchestra is in its deeper registers, ominous and more like something out of Journey to the Center of the Earth. The “greed” motif, stark and commanding, is a succinct five notes, the phrase repeated with a sixth note added. The motif is forever varied in key, rhythm and instrumentation, and appears incessantly throughout the film.

Most of the time, as in the very beginning of the journey when the little caravan reaches a chasm and passes through a valley, Herrmann’s orchestra is in its deeper registers, ominous and more like something out of Journey to the Center of the Earth. The “greed” motif, stark and commanding, is a succinct five notes, the phrase repeated with a sixth note added. The motif is forever varied in key, rhythm and instrumentation, and appears incessantly throughout the film.

As in several of Herrmann’s scores for 20th Century-Fox, Alfred Newman’s music behind the opening studio trademark and the CinemaScope extension is replaced by a totally Herrmannian main title.

The recurring criticism that the score, in stereo at its initial theatrical release, is too much in the foreground, though the music fills less than two-thirds of screen time, is partially true, but the film needs some help, and the composer brilliantly administers short-term resuscitation. After all, the composer, any composer, can only do so much. As Herrmann often told Zanuck, and it particularly applies to Garden of Evil, “I can dress the corpse, but I can’t bring it back to life.”

A perfect example of how films affects each of us differently. I’m a big fan of 50s westerns and this is one of my favorites. Great cast,scenery and Hermann’s exciting and atmospheric music.

I loved this movie and still do. For many years I have attempted to at least read in book form the script of the movie. It was a screen play! Simple story. Tidy and tight. Great cast and scenery. Drama. Forget the minor technicalities such as direction of movement in the escape sequence. I have a flick copy.

I agree with you in all respects, Vienna. To me this is my favourite 50s western.

One of my favorite movies. Great scenery and suspense.

While this film certainly has its faults, (as you have adroitly revealed), I must confess that I also enjoyed ” Garden of Evil”. Sometimes a film simply “clicks” in spite of itself, and for me, the participation of Cooper, Susan Hayward and Widmark excited my interest while the film itself provided good, if undemanding entertainment value.

The critic was obsessed with damning the movie by any means possible. In this he was successful. Still, Susan Hayward remains the reason I would jump a horse across a gap in a narrow canyon trail, coming and going for far less than 2 K in gold. I’m cheap. Cooper and Richard have choice bits of conversation, however terse. I liked the movie and still do.

Greg Orypeck–really?

I must also disagree with this critic. Far too often, western dramas are filled with overacting and flashy costumes. The dialogue in this screenpay is witty and clever, and the casting perfect. It is a treat to see two of cinema’s best performers, Widmark and Cooper, act alongside one another. This film, in fact, spurred my fascination with Richard Widmark, for which I am whole-heartedly greatful. I find this film to be one of the most poignant I’ve seen, western or otherwise, to date.

When GARDEN OF EVIL was released in 1954, I got to see the movie at the Carolina Theater, which is located in Spartanburg, SC. That theater had the gigantic widescreen, which made it a real pleasure to watch movies of that variety back then. But for a youngster of eight years-old, I was in awe. As the adventure unfolds and the four gents volunteer (for $$$$) to go with her to rescue her husband, I was struck by Susan Hayward’s dynamic, beautiful character that she portrayed. For a kid, she was mesmerizingly beautiful. She won my heart in John Wayne’s movie about “Genghis Khan.” I will forever remember her enchanting sword dance, after the other scantily clad dancers had performed.

As one becomes a tad older and movies changed to a certain degree, there could have been some scenes added to enchant the audience with an adult theme, especially camping near the river! But, one has to remember that the fifties are the not the 70s or even the 90s. But, Susan Hayward was an extremely beautiful lady.

As the adventure moves towards the rescue at the mine, the presence of Indians raises the anxiety of the rescuers and the couple. Somehow, the Indians didn’t have the look or the physicality of being Apache, but more like the Indians that chased Henry Fonda in the movie DRUMS ALONG THE MOHAWK. Also, someone pointed out to me that the rifles should have been pre-Civil War rifles and not the type used in the movie, “shoot for the entire week and twice on Sunday!”

But overall, I will forever keep this movie in my memories as one of my all-time favorite westerns.

Only recently discovered this movie. I love it !! My favorite western . I like that it’s different than the traditional western . Love Gary Cooper calm Kind unassuming but tough when he has to be. Always liked Richard Widmark. They the critics can bash it all they want I love it .

Love the Richard Widmark question Hooker what were you before you were a idiot looking for gold ? His reply an idiot without any.

I like the movie just because it’s western film and Rita Moreno was great too. I would like to know, the songs that Rita Moreno sings, are they sang only for that movie or I can buy them online or somehow? Thanks

The reason they stop to camp while fleeing is that unlike your Volvo, horses will die if you don’t feed, water and rest them. Perhaps audiences of 1954 had a better feel for this. Today all this has to be laid for people. Sorry this wasn’t a remake of The Treasure of Sierra Madre. Perhaps the director had something else in mind.

One of a few films I watch several times. I love the acting,story,scenery and the music. I know the ending but will still watch.

I too think it’s a terrific film; I only saw it first in my 20’s, but have seen it with great enjoyment several times since. Cooper and Widmark are great—especially Widmark as the cynic who is ultimately heroic. Susan Hayward is merely enigmatic, but “It’s Hayward—that’s enough.” The film lags in the middle but the first 45 minutes and last 25 minutes are exciting. The scenes along the Cliff are the best part: who can forget the terrifying gap in the Cliff trail that the horses have to leap over?