“I’ll follow him around the Horn, and around the Norway maelstrom, and around perdition’s flames before I give him up.”—— Captain Ahab (Gregory Peck)

“At sea one day, you’ll smell land where there be no land. And on that day Ahab will go to his grave, but he’ll rise again within the hour. He will rise and beckon, then all—all save one—shall follow.” It was old Elijah who, from behind crates on the wharf, gives this warning to the sea novice Ishmael and the harpooner Queequeg not to sail on the “Pequod.”

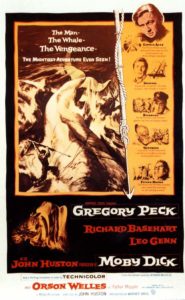

The warning was not heeded by these characters, nor the other kind of warnings director [intlink id=”10″ type=”category”]John Huston[/intlink] experienced, whispered in the ear of his mind, growing more premonitory as filming progressed, regarding the difficulties in making his twelfth theatrical movie, Moby Dick. For one thing—just look at the cast!—there are no women, a hard package to sell anytime to Hollywood, especially in the 1950s. Following close behind as a deterrent, the film hadn’t a particularly action-filled plot. Oh, it was about this crazy man in pursuit of a Great White Whale, but beyond the climax, granted, an exciting, somewhat metaphysical showdown between man and beast, there wasn’t much else except a lot of sailor talk, a little philosophizing, a bit of Biblical moralizing and a good deal of narration.

Which brings up another of Huston’s problems before the camera first rolled, and that was this colossus of a book, Herman Melville’s 1851 Moby-Dick—published with the hyphen—with all its stylized language, symbolism, anti-transcendental philosophy, a weightiness that compared with John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Both works have the somewhat similar thesis of good and evil, man’s struggle against the malevolent forces of the universe. Even Ahab, bearing the name of an evil king of the Old Testament, speaks in a Biblical vernacular, à la the King James version.

When John Huston wasn’t writing his own screenplays, he always had excellent co-writers, whether Christopher Fry (The Bible), Truman Capote (Beat the Devil), Richard Brooks (Key Largo), Arthur Miller (The Misfits) or Anthony Veiller (at least four Huston films, including The Night of the Iguana and Moulin Rouge).

When John Huston wasn’t writing his own screenplays, he always had excellent co-writers, whether Christopher Fry (The Bible), Truman Capote (Beat the Devil), Richard Brooks (Key Largo), Arthur Miller (The Misfits) or Anthony Veiller (at least four Huston films, including The Night of the Iguana and Moulin Rouge).

In Moby Dick, his co-writer was none other than Ray Bradbury. As Huston wrote in his autobiography, An Open Book, “I . . . saw something of Melville’s elusive quality in his work. . . . Highly original in his writing, from the idea itself to the very turn of a sentence, in casual intercourse Ray spoke entirely in clichés and platitudes.” When the science fiction writer joined Huston in Ireland for the collaboration, the director discovered Bradbury’s fear of riding in airplanes and in “fast” cars traveling over twenty m.p.h.

“Translating a work of this scope into a screenplay,” Huston summarized, “was a staggering proposition. Looking back now, I wonder if it is possible to do justice to Moby Dick on film.”

The next problem—in planning ahead, it had to be dealt with immediately—was the making of the models for the whale. Huston has written that there were three full-size, rather problematic “whales,” one which, he says, broke its towline and drifted into the open sea to become a shipping hazard. Another account, from the film’s cinematographer Oswald Morris, suggests there was never a full-sized model, only miniatures—if life-size, then only in parts, transported at sea on a barge, and used as needed. Otherwise, the interiors and whale close-ups were shot at Elstree Studios in England.

The next problem—in planning ahead, it had to be dealt with immediately—was the making of the models for the whale. Huston has written that there were three full-size, rather problematic “whales,” one which, he says, broke its towline and drifted into the open sea to become a shipping hazard. Another account, from the film’s cinematographer Oswald Morris, suggests there was never a full-sized model, only miniatures—if life-size, then only in parts, transported at sea on a barge, and used as needed. Otherwise, the interiors and whale close-ups were shot at Elstree Studios in England.

These “unbelievable misadventures,” as Huston called them, which rank with the difficulties of the director’s The African Queen, included a miscalculation in the costly dredging of the harbor at Youghal, near Cork City, Ireland, the stand-in for New Bedford. Huston wrote that the dredging for access by the “Pequod” was too shallow, meaning that “we could take the ‘Pequod’ in and out only at high tide—that is, during only about an hour a day.”

Ahab’s ship was modified from another vessel, with amateurish rigging and an added poop deck, but since the art of square-rigging had “gone with the past,” the lines were improperly and weakly rigged, resulting in two dismastings. And instead of placing the engines properly amidships, to save money Warner Bros. put them under the stern, so that the noise made it impossible to record dialogue.

(Note, here and later, the frequent quoting from the highly recommended An Open Book, a must-read for movie buffs, especially Huston aficionados.)

The plot is undoubtedly known, at least in its generalities, to practically everyone, although Philip Sainton, the British composer of the film’s score, admitted to being unfamiliar with the tome. The first line in the film is that of the book, one of the great openings in world literature—“Call me Ishmael.” It is spoken by this character (Richard Basehart), who narrates throughout the film.

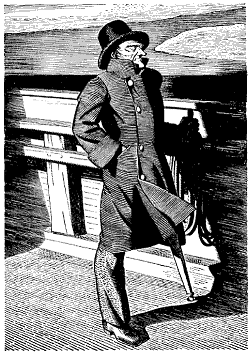

On a stormy night in 1841, Ishmael enters an inn filled with drinking, dancing, rowdy sailors. Stubb (Harry Andrews), second mate on the “Pequod,” praises the whale’s qualities and adds, “If God ever wanted to be a fish, he’d be a whale. Believe that, he’d be a whale.” At that moment, there are uneven footsteps from outside—plop, thud, plop, thud—and through the inn window is seen a tall man with a peg leg and a stovepipe hat. “That’s Ahab,” Stubb says, and when Ishmael asks who is Ahab, Stubb replies, “Captain Ahab to you. . . . Ahab’s Ahab.”

Ishmael, set on becoming a whaler himself, obtains a room for the night, unaware that his roommate is a former South Sea island cannibal, Queequeg (Friedrich Ledebur), with tattoos covering his whole body. Despite his fierce appearance, Queequeg is friendly and quickly makes a friend of Ishmael. After a sermon from Father Mapple (Orson Welles’ sole appearance), the two men sign up for passage on the “Pequod.” It was at this time that the two men are warned by Elijah (Royal Dano) not to sail on the vessel.

Ishmael, set on becoming a whaler himself, obtains a room for the night, unaware that his roommate is a former South Sea island cannibal, Queequeg (Friedrich Ledebur), with tattoos covering his whole body. Despite his fierce appearance, Queequeg is friendly and quickly makes a friend of Ishmael. After a sermon from Father Mapple (Orson Welles’ sole appearance), the two men sign up for passage on the “Pequod.” It was at this time that the two men are warned by Elijah (Royal Dano) not to sail on the vessel.

In a broad, vivid narration, Ishmael introduces the members of the crew, which maintains Melville’s cross section of humanity: the Quaker first mate Starbuck (Leo Genn); second mate Stubb, “carefree, foolish, laughing, wise Stubb”; ship’s carpenter (Noel Purcell, also in the 1962 Mutiny on the Bounty); the blacksmith (Ted Howard); the African native (Edric Connor) who “killed a lion with his bare hands and ate of its flesh”; the American Indian (Tom Clegg); the little black cabin boy Pip (Tamba Allenby); the Manxman (Bernard Miles, most famous for Joe Gargery in the 1946 Great Expectations); and other crew members played by Seamus Kelly and Mervyn Johns.

But where was Captain Ahab ([intlink id=”65″ type=”category”]Gregory Peck[/intlink])? Ishmael’s introduction of the crew is concluded with a shot of the closed doors of the great cabin. “Of our supreme lord and dictator, there was no sign. He stayed silently behind his locked door all the daylight hours.”

But where was Captain Ahab ([intlink id=”65″ type=”category”]Gregory Peck[/intlink])? Ishmael’s introduction of the crew is concluded with a shot of the closed doors of the great cabin. “Of our supreme lord and dictator, there was no sign. He stayed silently behind his locked door all the daylight hours.”

Ahab finally appears before the crew as some men are tarring the deck, in daunting aspect—not seen approaching, or emerging from a hatch or in some sort of panning shot up his body, but wholly there, in a sudden full-shot. Ishmael describes him: “Looming straight up and over us, like a solid iron figurehead suddenly thrust into our vision, stood Captain Ahab, his whole, high, broad form weighed down upon a barbaric white leg, carved from the jawbone of a whale. He did not feel the wind or smell the salt air; he only stood staring at the horizon, with the marks of some inner crucifixion and woe deep in his face.”

In the course of the film, before Ahab’s climactic combat with Moby Dick, there is the slaughter of one whale and the processing of its blubber for the oil that will “light the lamps of the world,” a kind of summary of the whaling process for the audience.

In the course of the film, before Ahab’s climactic combat with Moby Dick, there is the slaughter of one whale and the processing of its blubber for the oil that will “light the lamps of the world,” a kind of summary of the whaling process for the audience.

Later, a whole group (pod) of whales is sighted and harvesting begun, but when Captain Boomer (James Robertson Justice) of a passing ship comes aboard and casually mentions seeing a white whale, Ahab instantly abandons the hunt to go after his quarry. His pursuit is temporarily thwarted by a breezeless sea, and he directs that longboats pull the “Pequod” into a wind.

During the lull, Queequeg has premonitions of death and has the carpenter make him a coffin.

From another passing ship, the “Rachel,” the captain (Francis De Wolff) reports having seen a white whale several days earlier. Ahab is in such a hurry that he refuses to take time to render needed assistance to the captain whose son was killed by the whale. Ahab’s quest is again delayed, now by a storm, which no sea saga is every without. During the tempest, the crew witness a display of Elmo’s Fire, the weather phenomenon that causes the illumination of pointed objects, in this case Ahab’s harpoon. Ahab draws his fist down the shaft of his harpoon, extinguishing the violet glow.

Soon after the “mild, mild day” speech, when the “Pequod” is in the open sea, Ahab notices the air. “Do you smell it, lads—what the wind carries? . . . Aye, coral reef, green moss, shells, bits and pieces from all the oceans he ever swam through—an island to himself is the white whale.” Ishmael remembers aloud Elijah’s prophecy and repeats it to Ahab, who listens silently, knowingly, then from the masthead a shout comes that a whale has been sighted. Moby Dick!

Soon after the “mild, mild day” speech, when the “Pequod” is in the open sea, Ahab notices the air. “Do you smell it, lads—what the wind carries? . . . Aye, coral reef, green moss, shells, bits and pieces from all the oceans he ever swam through—an island to himself is the white whale.” Ishmael remembers aloud Elijah’s prophecy and repeats it to Ahab, who listens silently, knowingly, then from the masthead a shout comes that a whale has been sighted. Moby Dick!

Ahab joins the pursuit in one of the longboats, harpoon in hand, leaving Pip aboard to serve as “captain.” Even in his fervent hatred and driven madness, Ahab speaks admiringly of this dumb animal that has taunted him all these years, this whale that seems to have a mind of its own. “Ah, there’s majesty for you. Did you see the lances in his back? My lances—mine!—stuck in him years ago.”

As the whale attacks the longboats, Ahab grabs one of the harpoon lines that covers the body of Moby Dick, along with scars and protruding lances, and swings up on the animal. Lashed by wind and sea spray, he plunges his harpoon, again and again, into the animal’s flesh. “From hell’s heart, I stab at thee,” he screams. “For hate’s sake, I spit my last breath at thee, thou damned whale!”

As the whale attacks the longboats, Ahab grabs one of the harpoon lines that covers the body of Moby Dick, along with scars and protruding lances, and swings up on the animal. Lashed by wind and sea spray, he plunges his harpoon, again and again, into the animal’s flesh. “From hell’s heart, I stab at thee,” he screams. “For hate’s sake, I spit my last breath at thee, thou damned whale!”

Moby Dick makes a deep dive. When he resurfaces, with the now lifeless body strapped in place, Ahab’s right arm flops to and fro in the motion of the whale. “Ya see, ya see?” Stubb shouts. “Ahab beckons. He’s dead, but he beckons.” Now Starbuck, the passive Quaker, assumes his dead captain’s zeal. “After him!” he cries.

Moby Dick returns again and again, smashing all the longboats and ramming the “Pequod.” From the sunken ship, Queequeg’s empty coffin bobs to the surface, and upon it crawls the only survivor, Ishmael. He is picked up by the “Rachel,” and he concludes his narration: “The drama’s done. The great shroud of the sea rolls over the ‘Pequod,’ her crew, and Moby Dick. I only am escaped—alone, to tell thee.”

In the film, at least three excellent speeches are given to Ahab and delivered stoically, some say brilliantly, by Gregory Peck. Two are philosophical musings of a sort, and so extended and so rarely interrupted by other dialogue as to become colloquies.

In Ahab’s first appearance—aside from the intimations of his presence in that one distant shot and the sound of his pacing at night—he encourages his crew to join him in his unholy quest for the Great White Whale, which took off his leg. “Aye,” he says, “it was Moby Dick that tore my soul and body until they bled into each other.” He hammers to a mast a Spanish gold ounce, the prize for the sailor who first sights Moby Dick, and has the harpooners drink a toast. “Death to Moby Dick!” he says. “God hunt us all, if we do not hunt Moby Dick to his death! I’ll follow him around the Horn, and around the Norway maelstrom, and around perdition’s flames before I give him up.”

Peck’s delivery begins slowly and measured, as Ahab first misleads the crew with schoolboy questions. “What do ye do when ye see a whale, men?” But Peck/Ahab gradually becomes more and more vehement, and at the end there’s little doubt that the man is mad, bent on his crew’s—and the ship’s—destruction, if that is required to slaughter this demon leviathan.

Peck’s second speech occurs in his cabin when Starbuck realizes that Ahab’s careful tracking of whale migration throughout the world’s oceans is merely a scheme to seek out Moby Dick. When his first mate calls it blasphemous to search after a dumb brute that merely acted out of blind instinct, Ahab responds: “Speak not to me of blasphemy, man! I’d strike the sun if it insulted me. . . . Yet [Moby Dick] is but a mask. ’Tis the thing behind the mask I chiefly hate, the malignant thing that has plagued mankind since time began, the thing that maws and mutilates our race, not killing us outright but letting us live on, with half a heart and half a lung.” Pretty deep stuff, and a subdued Peck is nonetheless forceful—conveying a chilling Ahab in his godlike judgments.

Peck’s second speech occurs in his cabin when Starbuck realizes that Ahab’s careful tracking of whale migration throughout the world’s oceans is merely a scheme to seek out Moby Dick. When his first mate calls it blasphemous to search after a dumb brute that merely acted out of blind instinct, Ahab responds: “Speak not to me of blasphemy, man! I’d strike the sun if it insulted me. . . . Yet [Moby Dick] is but a mask. ’Tis the thing behind the mask I chiefly hate, the malignant thing that has plagued mankind since time began, the thing that maws and mutilates our race, not killing us outright but letting us live on, with half a heart and half a lung.” Pretty deep stuff, and a subdued Peck is nonetheless forceful—conveying a chilling Ahab in his godlike judgments.

The third and best of Peck’s extended speeches opens with reference to the “mild, mild day” (a “mild, mild wind” in the book), again with Starbuck present but saying little. In the beginning of the film, before Ahab had spoken his first words, Stubb had said proudly, “Ahab’s Ahab,” implying a self-confident captain.

Now, maybe doubting his own strength, maybe his very existence, Ahab makes of the words a question. “Is Ahab Ahab? Is it I, God, or who that lifts this arm? But if the great sun cannot move except by God’s invisible power, how can my small heart beat, my brain think thoughts, unless God does that beating, does that thinking, does that living, and not I?” Having earlier elevated himself to God status in threatening to strike the sun if it insulted him, he now concedes control of the sun to God. Near the end of his delivery, Ahab repeats the “mild, mild day” line, like a carefully scripted soliloquy. (Incidentally, during this speech in Chapter CXXXII, Ahab refers to his wife—“rather a widow with her husband alive”—who is omitted in the film’s script, presumably to help make Ahab less human.)

Now, maybe doubting his own strength, maybe his very existence, Ahab makes of the words a question. “Is Ahab Ahab? Is it I, God, or who that lifts this arm? But if the great sun cannot move except by God’s invisible power, how can my small heart beat, my brain think thoughts, unless God does that beating, does that thinking, does that living, and not I?” Having earlier elevated himself to God status in threatening to strike the sun if it insulted him, he now concedes control of the sun to God. Near the end of his delivery, Ahab repeats the “mild, mild day” line, like a carefully scripted soliloquy. (Incidentally, during this speech in Chapter CXXXII, Ahab refers to his wife—“rather a widow with her husband alive”—who is omitted in the film’s script, presumably to help make Ahab less human.)

Peck’s performance was criticized by some reviewers as wanting, that he was essentially too shallow an actor to bring off the subtleties required for so nuanced and introspective a character. Huston felt otherwise, that Peck “brought a superb dignity to the role. . . . I can’t imagine the ‘It’s a mild, mild day . . . ’ speech being better spoken by any actor.” Myself, I believe Peck wisely underplayed the role, avoiding the obvious pitfall of overdoing Ahab as a raving maniac and a religious zealot with a God complex, which, of course, he was.

Rumors have persisted through the years that John Huston wanted, first, Orson Welles to play Ahab and, second, that he easily saw himself in the part, as he had played a true Biblical figure, Noah, in his later film The Bible (Ahab occasionally has the trappings of an angry prophet). Peck was later reported to have thought that Huston would have made a good Ahab. If the director is not seen in Moby Dick, he is at least heard, in the cry of a masthead lookout and in dubbing the voice of the innkeeper (Joseph Tomelty), which required uncharacteristically hurried speech for Huston.

Rumors have persisted through the years that John Huston wanted, first, Orson Welles to play Ahab and, second, that he easily saw himself in the part, as he had played a true Biblical figure, Noah, in his later film The Bible (Ahab occasionally has the trappings of an angry prophet). Peck was later reported to have thought that Huston would have made a good Ahab. If the director is not seen in Moby Dick, he is at least heard, in the cry of a masthead lookout and in dubbing the voice of the innkeeper (Joseph Tomelty), which required uncharacteristically hurried speech for Huston.

The desaturated color that Huston wanted from the screen—“the strength found in steel engravings of sailing ships”—was ideally replicated in Philip Sainton’s score, heavily weighed toward woodwinds and brass to give a hard, steely patina to the music. The much-clichéd preparations for setting sail, a requisite for all sea sagas, since all voyages must begin, is one of the few uplifting moments in music that is mostly dark and moody, even sometimes tortuously harsh. The majority of the score reinforces the philosophical underpinnings of the story line, conveying as well the hard and dangerous life of sailors who hunted whales.

Sainton, an obscure British composer and eager for recognition, took on his first film score with much excitement and anticipation. Where most film composers, even the experienced ones, are annoyed by the restrictions of the work—attaching an art form to one already created, having to write quickly and bowing to the whims of usually musically ignorant directors—Sainton found this new world a challenge and, ultimately, highly successful.

Fortunately Sainton was working with a sensitive, understanding director. When the composer, aware he was a slow worker, insisted that he could not compose the score in the mere six weeks that would be allotted him and wanted to start immediately on creating themes and motifs, Huston invited him to the set. Sainton not only expertly adapted to the film-scoring process, perhaps because he enjoyed the experience so much, but he produced a near-great score—not an heroic water-splasher like Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s The Sea Hawk, but a dark sea saga with a Hamlet-like figure on board, in this case an Ahab.

Fortunately Sainton was working with a sensitive, understanding director. When the composer, aware he was a slow worker, insisted that he could not compose the score in the mere six weeks that would be allotted him and wanted to start immediately on creating themes and motifs, Huston invited him to the set. Sainton not only expertly adapted to the film-scoring process, perhaps because he enjoyed the experience so much, but he produced a near-great score—not an heroic water-splasher like Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s The Sea Hawk, but a dark sea saga with a Hamlet-like figure on board, in this case an Ahab.

It is not “sea music” in the traditional sense, for it is without the sweet fragrance of salt air or the rhapsodic whish of a sea breeze. Already, at the outset, the main title contains an angry and harsh motif for Ahab, then an even more aggressive idea for Moby Dick and, last, a full-length theme, the softest of all, for the doomed “Pequod.”

Among the more than twenty-four cues, there are musical ideas for Queequeg, the two-note undertow for Elijah’s dire prophecy and many more. The composer inserts “A-Rovin’” and “Hill an’ Gully Rider,” two of several traditional tunes that add color to this portrayal of sailors’ lives. And Huston asked Sainton to set a melody for Melville’s hymn “The Ribs and Terrors in the Whale” that occurs in Chapter IX of the book and, in the film, is sung before Father Mapple’s sermon.

The longest cue (apart from the climax), though broken by silences, accompanies Ahab’s introduction and his fiery address to the crew, beginning with the Ahab motif and followed by music that, like Ahab’s speech, is alternately vehement and quiet. The score here is perhaps most chilling when, as the captain’s voice drops to a deep whisper, the timpani deliver soft, ominous taps.

The longest cue (apart from the climax), though broken by silences, accompanies Ahab’s introduction and his fiery address to the crew, beginning with the Ahab motif and followed by music that, like Ahab’s speech, is alternately vehement and quiet. The score here is perhaps most chilling when, as the captain’s voice drops to a deep whisper, the timpani deliver soft, ominous taps.

At the end of the movie, in the finish of this enormous allegory if you will, when the “Pequod” sinks, there is a recapitulation of at least three of the ideas—first the four-note Ahab motif as he is seen for the last time, the seemingly triumphant music for Moby Dick—for, after all, hasn’t he won the fight?—and, last, Elijah’s dark warning motif.

As to a possible source of the score’s success, Sainton was quite generous toward one person in particular: “ . . . John Huston has a great understanding of music and knows exactly the kind of sound he wants for each sequence in his films. He told me that I must treat Moby Dick just as if I were writing an opera. There were no words that I better wanted to hear. This treatment ideally suited my own inclinations . . . ”

It must be remembered, too, that Sainton, although French-born, grew up in Britain, an island nation with a great nautical tradition. After all, Britain had ruled the seas for hundreds of years. Practically every British composer, then, wrote sea music: Vaughan Williams a “Sea” Symphony and an opera Raiders to the Sea, Stanford several sets of sea songs, Bantock A Hebridean Symphony and Elgar a vocal cycle, Sea Pictures. Rest assured, this is only a partial list. Britten wrote at least two sea operas, Peter Grimes and Billy Budd. This last, incidentally, is based on Melville’s last, incomplete novel.

Highly enlightening . Analytically perceptive. Much enjoyed . Thank you.

Agree. Although the distance of time ought to dim the impact yet it abides.

I am waiting for the last remake, with Raymond Massey, Gregory Peck, and Patrick Stewart all on the side of the whale, arguing about whose whale it is, and shouting “get off my whale”! They can do wonders with GCI now, and this would be really neat to see….

An interesting and little-known side note: Orson Welles directed Rod Steiger in a stage version of Melville’s novel called “Moby-Dick: Rehearsed”