“They talk about flat-footed policemen. May the saints protect us from the gifted amateur.” —— Chief Inspector Hubbard (John Williams)

In 1948, [intlink id=”8″ type=”category”]Alfred Hitchcock[/intlink], by then well established in Hollywood, had experimented in shooting an entire film, Rope, without cuts or editing, in continuous reels of film, and four films earlier—his seventh in Hollywood—he had limited himself in yet another way by setting an entire film, Lifeboat, in such a sea-going craft. These were two challenges Hitch set for himself—the first unsatisfactory, the second a guarded triumph; but he never fully tackled either technique again.

In 1954, another challenge was more or less forced on him. Warner Bros. at the time was in the financial doldrums, suffering, as were all the studios, from the advent of practical television and its growing popularity. CinemaScope, launched by 20th Century-Fox in 1953 with The Robe, was just one attempt to lure viewers to the theaters. Still another was impractical 3-D, short-lived until its recent revival in selected action films.

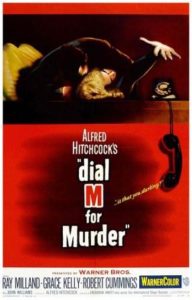

In Dial M for Murder, the first movie to be made after Warner’s supposed new strategy to regain audiences, was to be filmed in 3-D. Hitchcock, unexcited by the new process from the first, immediately saw its limitations. The two bulky cameras—even bulkier than the Technicolor ones, and this film would be in color—meant limited angles and restricted movement, both important trademarks in Hitch’s screen persona. Since the film was based on Frederick Knott’s stage play—the Englishman also wrote the screenplay—the director filmed it in a more or less straightforward manner, as a play, limiting himself to basically one set, a London flat, and going “outside” as little as possible.

The few 3-D effects, though none are over-the-top, did emphasis an open lady’s purse, a key inserted into a door lock and the murder weapon, a soon-to-be famous pair of scissors. The cameras are usually kept low, their limited mobility compensated by more than the usual amount of Hitchcock close-ups. The generally stationary cameras, however, would be partially freed on at least two occasions—an overhead shot of the two men planning the murder and a revolving shot of the victim on a desk top struggling against the assailant.

The few 3-D effects, though none are over-the-top, did emphasis an open lady’s purse, a key inserted into a door lock and the murder weapon, a soon-to-be famous pair of scissors. The cameras are usually kept low, their limited mobility compensated by more than the usual amount of Hitchcock close-ups. The generally stationary cameras, however, would be partially freed on at least two occasions—an overhead shot of the two men planning the murder and a revolving shot of the victim on a desk top struggling against the assailant.

By the time of its release, interest in the new process already fading, the film was generally issued “flat,” though special showings were in 3-D.

While Dial M for Murder would be the last of four films Dimitri Tiomkin would score for Hitchcock, cinematographer Robert Burks was just beginning his long association with the director. This was the third of twelve films he would shoot, beginning with Strangers on a Train and ending with Marnie, and ending then only because of his death in 1968. Dial M for Murder was the first of three films starring Hitch’s most famous female star, [intlink id=”301″ type=”category”]Grace Kelly[/intlink], who would greatly disappoint him by marrying Prince Rainer of Monaco in 1956.

The film begins with the arrival in London of detective writer Mark Halliday (Robert Cummings), former, and current, lover of Margot Wendice (Kelly), whose husband Tony (Ray Milland) knows of their affair a year earlier. Margot has destroyed all but one of Mark’s love letters; that one she always transferred from one handbag to another—until it was stolen, stolen by Tony who blackmailed her anonymously.

The film begins with the arrival in London of detective writer Mark Halliday (Robert Cummings), former, and current, lover of Margot Wendice (Kelly), whose husband Tony (Ray Milland) knows of their affair a year earlier. Margot has destroyed all but one of Mark’s love letters; that one she always transferred from one handbag to another—until it was stolen, stolen by Tony who blackmailed her anonymously.

Tony, always debonair and a perfect host, has retired from professional tennis and needs money. His wife’s fortune seems the ideal solution, so he plans to murder her—rather, have her murdered by a shady character, Swann (Anthony Dawson, who would reprise the role in a 1958 TV movie). Tony has been carefully shadowing him for blackmail evidence.

Feigning work he needs to do, Tony stays home while Margot and Mark go out for the evening. Using another name and on the pretext of wanting to buy a car Swann has for sale, Tony phones and invites him over. Instead of arguing car prices, in a twenty-minute scene Tony outlines his plan for Swann to kill his wife, using blackmail as coercion. (Tony and Swann had attended the same university. Though they were not in the same class, in the photo Tony shows Swann they appear incorrectly together at “their” class reunion. It’s also Hitch’s chance to make his traditional cameo appearance, seated among the alumni.)

Feigning work he needs to do, Tony stays home while Margot and Mark go out for the evening. Using another name and on the pretext of wanting to buy a car Swann has for sale, Tony phones and invites him over. Instead of arguing car prices, in a twenty-minute scene Tony outlines his plan for Swann to kill his wife, using blackmail as coercion. (Tony and Swann had attended the same university. Though they were not in the same class, in the photo Tony shows Swann they appear incorrectly together at “their” class reunion. It’s also Hitch’s chance to make his traditional cameo appearance, seated among the alumni.)

Per the murder plan, Tony takes Mark to a stag party while Margot stays home to listen to a favorite radio program. Tony had stolen from her purse her latchkey, which he hid under the hall stair carpet outside their flat door. Swann will arrive that night before eleven, open the door with the key, hide behind a curtain and wait for Tony’s phone call at eleven. Margot will come out from her bedroom to answer the phone on the desk beside the curtain. Tony will thus have an alibi—and a room full of witnesses, including Mark.

In the first hitch in Tony’s plan, his watch has stopped. By the time he realizes it and goes to the restaurant phone, he is late and someone is in the booth. Back at the flat, Swann is impatient when the phone doesn’t ring on schedule and is half way out the door.

(Here is one of those occasions where Hitchcock, his usual expansive imagination now constricted by the gimmick of 3-D, decides to do something he does best, play with the audience’s emotions. As he did in Psycho, getting the audience to want the thief Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) to get away with stealing the $40,000, he now tricks the audience into wanting the phone to ring and Swann to wait for his victim.)

(Here is one of those occasions where Hitchcock, his usual expansive imagination now constricted by the gimmick of 3-D, decides to do something he does best, play with the audience’s emotions. As he did in Psycho, getting the audience to want the thief Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) to get away with stealing the $40,000, he now tricks the audience into wanting the phone to ring and Swann to wait for his victim.)

When Tony does make his phone call—Tiomkin’s music accompanying with a bit from the “Coronation Scene” in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov—Swann returns behind the curtain when the rings finally come. When Margot answers the phone and there is no voice on the other end, she repeats “Hello! Hello! Hello!” about seven times. Anyone else would have hung up long ago, but it’s done to heighten the suspense—and because Swann is waiting for her to lower her arm, so the curtain sash he holds can make direct contact with her throat. Strangulation, one of Hitch’s favorite murder methods.

With Tiomkin’s dissonant music, Dawson situated over Kelly and Burks’ shots of her legs, the choking is something akin, in all its convulsions, to a wild seduction. This, too, seems prolonged, but it is, after all, Hitch’s set piece of the movie. Margot’s spread fingers function enough to grope for, then grasp, a pair of scissors. Into Swann’s back she buries the so-called “blunt” half of the blades; the other half, with its pointed tip, would have rendered better penetration, but perhaps even Hitch’s concern for detail wasn’t that exacting in this instance. Swann stiffens backward, staggers and falls to the floor, face up, the blade driven deeper into his back, which, on screen, is somehow more horrifying than the initial stabbing.

With Tiomkin’s dissonant music, Dawson situated over Kelly and Burks’ shots of her legs, the choking is something akin, in all its convulsions, to a wild seduction. This, too, seems prolonged, but it is, after all, Hitch’s set piece of the movie. Margot’s spread fingers function enough to grope for, then grasp, a pair of scissors. Into Swann’s back she buries the so-called “blunt” half of the blades; the other half, with its pointed tip, would have rendered better penetration, but perhaps even Hitch’s concern for detail wasn’t that exacting in this instance. Swann stiffens backward, staggers and falls to the floor, face up, the blade driven deeper into his back, which, on screen, is somehow more horrifying than the initial stabbing.

(Hitchcock spent a week on filming this one scene. One recurring problem was that the camera did not pick up the reflection off the scissors to his satisfaction. As has come down over the years from the lore attached to this “master of suspense,” in discussing Dial M for Murder in an interview, he said, “As you have seen on screen, the best way to do it is with a scissor.”)

With Margot’s unexpected survival, there’s another hitch in Tony’s plan for a perfect murder. Before silent, he now responses to her desperate pleas over the phone and speaks up, having heard the terrible struggle over the dropped receiver. He tells her to sit tight until he arrives. While she retreats to the bathroom for an aspirin, he removes a latchkey from Swann’s pocket—he assumes the key to the apartment door—and places it in Margot’s purse. He then slips into the dead man’s pocket the love letter from Mark, which Tony has in his wallet. Plan Two has just been initiated: Margot will be convicted for killing the blackmailer of her lost letter.

With Margot’s unexpected survival, there’s another hitch in Tony’s plan for a perfect murder. Before silent, he now responses to her desperate pleas over the phone and speaks up, having heard the terrible struggle over the dropped receiver. He tells her to sit tight until he arrives. While she retreats to the bathroom for an aspirin, he removes a latchkey from Swann’s pocket—he assumes the key to the apartment door—and places it in Margot’s purse. He then slips into the dead man’s pocket the love letter from Mark, which Tony has in his wallet. Plan Two has just been initiated: Margot will be convicted for killing the blackmailer of her lost letter.

Unfortunately for Tony, the police official investigating the case is the urbane, shrew Chief Inspector Hubbard (John Williams, a Hitch favorite, appearing in three of his films and ten TV episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents). Hubbard has a Columbo-like mind—Williams, in fact, would appear in a Columbo episode, “Dagger of the Mind,” in 1972—and, like Columbo, is methodical, analytical and intuitive, almost immediately zeroing in on the killer from among a slue of suspects.

While Hubbard does carry a raincoat, the similarities with the Peter Falk character end with his impeccable attire and touch of arrogance, but he does deliver a Columbo-like remark, prophetically similar to so many variations on Columbo’s most famous line, “Oh, just one more thing—” Hubbard actually says, “Just one other thing, sir—”

And now for the climax of Dial M for Murder——

Although throughout most of the film Hubbard, like everyone else, seems to assume Margot is guilty of murder—and she is so convicted and sentenced to death—his doubts persist. “My blood was up!” he says. The crux of the mystery centers around latchkeys, which Hubbard alone understands, and he is annoyed by the inert amateur advice from the bland Mark. “That’s the trouble with all these latchkeys,” he says. “They’re all alike.”

Hubbard figures out that rather than wait until after the deed was done, Swann returned the key to its hiding place under the stair carpet before he entered the flat, and the latchkey which Tony found in Swann’s pocket and placed in Margot’s purse was the dead man’s own latchkey! “Mine you,” Hubbard says, “even I didn’t guess that at once. Extraordinary.”

Hubbard figures out that rather than wait until after the deed was done, Swann returned the key to its hiding place under the stair carpet before he entered the flat, and the latchkey which Tony found in Swann’s pocket and placed in Margot’s purse was the dead man’s own latchkey! “Mine you,” Hubbard says, “even I didn’t guess that at once. Extraordinary.”

Though surely violating the law, as a test he has Margot released from prison, accompanied by two clothed policemen. If she had murdered Swann, when she found that the key in her purse would not open the front door, she would retrieve the key from under the stair carpet. Instead, she remains locked out of the flat and confused by her non-functioning key.

Next, Hubbard will test his real suspect. He had made a farewell and “thank you” to Tony, affecting an end to the case. He then had Margot’s purse with Swann’s key returned to the police where Tony would sign for the possessions of the condemned. “Make sure he sees the key,” Hubbard tells the policeman on the telephone.

Hubbard, Margot and Mark wait in the darkened apartment for Tony’s return home. Tony finds that the key in the purse does not open the door. He walks away, reaching the sidewalk before he pauses and returns. “He’s remembered!” Hubbard says as he peeks outside between the curtains. Tony lifts the edge of the carpet, removes the key, directs it slowly toward the lock (a 3-D opportunity), enters the apartment and turns on the light. Surprise! He attempts to retreat through the door but a policeman bars the way. He turns nonchalantly to his hosts and offers everyone a drink. He is, after all, Tony Wendice, still debonair and, as always, seemingly unruffled.

Hubbard, Margot and Mark wait in the darkened apartment for Tony’s return home. Tony finds that the key in the purse does not open the door. He walks away, reaching the sidewalk before he pauses and returns. “He’s remembered!” Hubbard says as he peeks outside between the curtains. Tony lifts the edge of the carpet, removes the key, directs it slowly toward the lock (a 3-D opportunity), enters the apartment and turns on the light. Surprise! He attempts to retreat through the door but a policeman bars the way. He turns nonchalantly to his hosts and offers everyone a drink. He is, after all, Tony Wendice, still debonair and, as always, seemingly unruffled.

Margot and Mark, themselves unusually unruffled, accept a drink as entirely appropriate, while Chief Inspector Hubbard declines, instead proudly combing his mustache.

Dial M for Murder is a thoroughly polished affair—a good script well delivered by at least four of the five leading players. Milland, Kelly and Dawson are great in their roles and certainly so is Williams, who threatens to steal the show. Only Cummings, often blending into the wallpaper, or, at other times, standing out as garishly miscast, seems too light, even for this high-class drawing room mystery. In his first appearance, when he disembarks the Queen Mary, Cummings is grinning like a boy who has just gotten away with some dastardly trick, and a variation of this smirk resurfaces on occasions, even when he’s trying to be serious.

In a variation on a scheme Hitchcock had used before, that of dressing actresses to match the changing moods and situations on screen, Grace Kelly’s dresses gradually become more somber, representing her declining status. For the close-up of the rotary dial when Milland is making his fateful phone call, Hitch had to build an enormous telephone with an equally large wooden finger. The two 3-D cameras could not focus sharply enough on a conventional phone.

In a variation on a scheme Hitchcock had used before, that of dressing actresses to match the changing moods and situations on screen, Grace Kelly’s dresses gradually become more somber, representing her declining status. For the close-up of the rotary dial when Milland is making his fateful phone call, Hitch had to build an enormous telephone with an equally large wooden finger. The two 3-D cameras could not focus sharply enough on a conventional phone.

Tiomkin’s music supports the film admirably. Although his arresting, outdoorsy opening of the main title, minus Max Steiner’s old trademark fanfare, which was excised as a preface to Warner films by 1954, might just as easily herald a Western. The following waltz is overused in the film’s first part, though a brief solo violin is enchanting—perhaps deliberate efforts to deceive the audience into thinking the forthcoming is to be a light romantic comedy, though, in a Hitchcock film, who would ever think that?! Tiomkin, however, quickly finds his feet, as it were, in the highly dissonant music for Swann’s death, the motif for Milland’s treachery and the often-heard rhythmic, ticking-like stretches that give the music—and the film—a sympathetic forward motion in the dénouement.

In this movie everyone seems so civilized—another phrase comes to mind: “so English”—while below the surface is an undertow of deceit and treachery. It might be appropriate here to illustrate that beneath Hitchcock’s façade of the refined English gentleman, though he was that, among other things, was a man who enjoyed practical jokes, bawdy talk and sexual innuendo.

As Donald Spoto relates in his must-read biography of the director, The Dark Side of Genius, Grace Kelly tells how Hitch turned to her during filming after he had told Ray Milland “some very raw kinds of things.” He asked if she was shocked. “No,” she replied. “I went to a girl’s convent school, Mr. Hitchcock. I heard all those things when I was thirteen.” And, of course, Hitch loved it.

Great review. I too thought Robert Cummings was miscast. Too bland.

I also thought Ray Milland was too old to be playing a recently retired professional tennis player.