Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred:

“Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns,” he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

—opening of The Charge of the Light Brigade by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

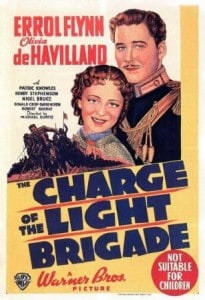

Considering that anything close to sophisticated film scoring hadn’t been around all that long, 1936 was a reasonably good music year for the movies. The clear, hands down winner of the Best Score Oscar was Erich Wolfgang Korngold for Anthony Adverse. Fellow Warner Brothers composer Max Steiner received two nominations, for The Charge of the Light Brigade and The Garden of Allah for the Selznick Studios. The two other nominees were Werner Janssen for The General Died at Dawn and Nathaniel Shilkret for Winterset. Though now generally forgotten, both men had not only distinguished music careers but long, productive lives.

Also in 1936, director Charlie Chaplin, who also dabbled at scribbling music, wrote for his Modern Times melodies that were transformed into score form by composer David Raksin and orchestrator Eddie Powell. Alfred Newman was active that year with Dodsworth and These Three, scores that were pale shadows of his lyrical, polished style to come. More impressive was the work of Virgil Thomson, one of those so-called “serious” composers, as distinguished from that other—some say “lower”—breed of men who write film music. As Steiner often did, Thomson incorporated popular and traditional tunes in an over-all impressive score for the government-sponsored documentary The Plow That Broke the Plains.

The Charge of the Light Brigade was, in fact, Steiner’s initial score under a first-time Warners contract—the film and the score were great successes—though the composer continued to do independent work for other studios, especially for David O. Selznick, most famously for a little ditty titled Gone With the Wind.

Of course, being Steiner, he opens the main title of Charge—here minus his own Warners signature fanfare—with his first borrowing, “Rule Britannia,” rousingly scored and entirely appropriate as the signature tune of imperial Great Britain, the ruler of the waves, that empire upon which the sun never sets, the nineteenth-century manifestation of parasitic colonialism. There is still time in the main title for Steiner’s principal theme, “Forward the Light Brigade,” a march more jaunty than stirring, far from imperialistic, which is varied throughout the movie.

The climax of the film—and the highlight as well—is inspired by Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s famous poem. Film and poem recreate the charge of British light cavalry against a prepared, well-defended Russian force during the Battle of Balaklava (1854) in the Crimean War, a charge as foolish as General George Pickett’s infantry advance at Gettysburg nine years later—and in both cases across open terrain and against overwhelming odds.

To accompany the charge, Steiner now mingles “Rule Britannia” with the old Russian Imperial anthem “God Save the Czar” in a musical mêlée as exhilarating as the screen visuals themselves. It is one of the great set battles in cinema, lasting nine minutes and recalling a similar one, some say even more complicated and exciting—the Battle of the Little Big Horn in They Died With Their Boots On (1942), from the same studio, and with the same composer and “doomed” actor (Errol Flynn). Instead of the ominous “Sioux” theme” in Boots, with its shrieking high woodwinds (six flutes/six clarinets), Steiner recalls in Charge the march tune as the cavalry begins its advance across the valley, the horses’ walk growing to a trot, then to a gallop. The march melody later evolves into an heroic, mesmerizing proclamation, despite the extravagance of this military blunder.

Though the charge and the music share center place in The Charge of the Light Brigade—a lesser account was filmed in 1968 with Trevor Howard and Vanessa Redgrave—there are, of course, other elements to be considered in this 1936 version. One is the script, which, like most scripts in the Hollywood meat grinder of changes and shifting emphases, underwent a distinct departure from Michel Jacoby’s collection of ideas about the Crimean War. With the recent success in 1934 of another movie set in India, Paramount’s The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, Warners decided the charge at Balaklava would be retained as the climax, but most of the film would contain other action, intrigue and a sizable love story, but centered in India.

Jacoby and co-screenwriter Rowland Leigh thus accommodated the studio and produced an adventure more out of Kipling than Tennyson. Stationed in India with the 27th Lancers, Captain Geoffrey Vickers (Flynn), soon to be promoted to major, journeys to Arabia to purchase horses for the British army. For there are disturbances in the Balkans between England and her allies and Russia and hers, and everyone fears coming war.

Jacoby and co-screenwriter Rowland Leigh thus accommodated the studio and produced an adventure more out of Kipling than Tennyson. Stationed in India with the 27th Lancers, Captain Geoffrey Vickers (Flynn), soon to be promoted to major, journeys to Arabia to purchase horses for the British army. For there are disturbances in the Balkans between England and her allies and Russia and hers, and everyone fears coming war.

En route, Vickers’ regiment stops at Calcutta. Since his last visit, his fiancée Elsa (Olivia de Havilland) has fallen in love with Geoffrey’s brother Perry (Patric Knowles), but she feels obligated to marry Geoffrey, and her father Captain Campbell (Donald Crisp) is adamant that she remain true to her fiancé. Also in Calcutta, for comic relief more than anything else, are Sir Warrenton and his wife (Nigel Bruce and Spring Byington in another ditsy role).

The villain of the film, rajah Surat Khan (a regally evil C. Henry Gordon), displeased by his treatment from the British and having sided with Russia, massacres the Lancers at the Chukoti garrison. Many are killed including Captain Campbell and women and children, but Geoffrey and Elsa are able to escape. The survivors, who declare revenge, are next assigned to the Crimea. Geoffrey learns that Surat Khan is with the Russian forces at Balaklava, and when he is dictated a dispatch by Sir Charles Macefield (Henry Stephenson) ordering the Lancers to retreat, Geoffrey substitutes an order for the brigade to attack.

The villain of the film, rajah Surat Khan (a regally evil C. Henry Gordon), displeased by his treatment from the British and having sided with Russia, massacres the Lancers at the Chukoti garrison. Many are killed including Captain Campbell and women and children, but Geoffrey and Elsa are able to escape. The survivors, who declare revenge, are next assigned to the Crimea. Geoffrey learns that Surat Khan is with the Russian forces at Balaklava, and when he is dictated a dispatch by Sir Charles Macefield (Henry Stephenson) ordering the Lancers to retreat, Geoffrey substitutes an order for the brigade to attack.

In the course of the movie, before Surat Khan turns nasty, there’s a ball, a leopard hunt, Geoffrey saves the rajah’s life and, after first denying the obvious for the longest time (her soulful face should have told him something!), he accepts the truth about Elsa’s feelings for his brother. To save Perry, he orders him to take a note to Macefield explaining what he has done. The 27th Lancers attack and are defeated, but not before Geoffrey kills Surat Khan at the cost of his own life.

As the disclaimer reveals at the beginning of Charge, history suffers grievously in this movie. Most, if not all, of the actual historical names have been changed, and many so-called “real” characters are entirely made-up, most notably Surat Khan. There was no 27th Lancers in the British army—at least not until 1941; several Lancer brigades, not to mention some Hungarian light dragoons, made the actual charge. The Battle of Balaklava, whose date is stated incorrectly in the film (surely easy enough to get right!), did not cause the fall of Sevastopol as implied.

As the disclaimer reveals at the beginning of Charge, history suffers grievously in this movie. Most, if not all, of the actual historical names have been changed, and many so-called “real” characters are entirely made-up, most notably Surat Khan. There was no 27th Lancers in the British army—at least not until 1941; several Lancer brigades, not to mention some Hungarian light dragoons, made the actual charge. The Battle of Balaklava, whose date is stated incorrectly in the film (surely easy enough to get right!), did not cause the fall of Sevastopol as implied.

In one battle sequence, the model of rifle used is American and not developed until years later. On several occasions, as so often in Hollywood films, the Union Jack is flown upside-down. And most misleading of the errors, the famous charge was not directed out of personal revenge but the result of a quarrel between real-life personalities, FitzRoy Somerset, Lord Raglan, and James Brudenell, Earl of Cardigan, here possibly going under the names of Macefield and Warrenton.

But, hey!, this film is great fun and, besides, who cares?

Charge is one of only two of the nine Flynn/de Havilland films in which he dies, the other being They Died With Their Boots On. In his first film since Captain Blood, the actor is supremely more self-assured, more charming, more romantic, a better actor, though there was nothing seriously wrong with Flynn’s performance in that pirate movie; his persona there seems to match the less sophisticated trappings of the film itself. In Charge, his British accent fits perfectly in time and place, while nine films later, although it would seem anachronistic in the Western Dodge City, no one seemed to mind.

Charge is one of only two of the nine Flynn/de Havilland films in which he dies, the other being They Died With Their Boots On. In his first film since Captain Blood, the actor is supremely more self-assured, more charming, more romantic, a better actor, though there was nothing seriously wrong with Flynn’s performance in that pirate movie; his persona there seems to match the less sophisticated trappings of the film itself. In Charge, his British accent fits perfectly in time and place, while nine films later, although it would seem anachronistic in the Western Dodge City, no one seemed to mind.

With a slightly larger part than in Captain Blood, Olivia, too, is better dressed and coiffured. Her love scenes, maybe because she isn’t in love with Flynn this time around, become more and more tedious, perhaps the chief weakness of the film. Tedious because, for one reason, the weak-willed Elsa—a trait clearly uncharacteristic of Olivia the actress and woman—continually puts off telling Geoffrey the truth until the last moment, and as for Geoffrey’s share in all this subterfuge, he seems too dense to read her face or believe Perry’s repeated declaration. Beyond this, her preference for the dull Knowles over the full-blooded Flynn is hard to understand. Even if in a much smaller part, the lightweight Knowles would be better used as Will Scarlet in The Adventures of Robin Hood, his next film with Flynn.

Speaking of Captain Blood, it’s interesting to note, for those who relish such analysis, how many of the players from that movie reappear in Charge, not unexpected considering the mingling of actors among both Warner films and those of other studios. There are obviously Flynn and de Havilland but also Stephenson, E. E. Clive, Robert Barret (always changing costumes), J. Carrol Naish (a thankless role) and Colin Kenny and Holmes Herbert (both lost in the crowds).

Speaking of Captain Blood, it’s interesting to note, for those who relish such analysis, how many of the players from that movie reappear in Charge, not unexpected considering the mingling of actors among both Warner films and those of other studios. There are obviously Flynn and de Havilland but also Stephenson, E. E. Clive, Robert Barret (always changing costumes), J. Carrol Naish (a thankless role) and Colin Kenny and Holmes Herbert (both lost in the crowds).

As in Captain Blood, Michael Curtiz renders agile, sure-footed direction, always with those trademark shadows on the wall, especially in the beginning of the film. Against the two unsuccessful Oscar nominations (Score and Sound), the film did win for Assistant Director (Jack Sullivan), an Oscar classification dropped after 1937. Although Sullivan was largely responsible for the climactic charge, it would be incorrect to assume Curtiz didn’t have a substantial part in that direction as well.

It was during the filming that Curtiz, the Hungarian notorious for his fractured England, supposedly made his famous remark, “Bring on the empty horses.” David Niven, who dies in the Chukoti massacre, used the phrase as a title for his 1975 raconteur-style survey of the “mishmash” that was Tinsel Town between 1935 and 1960.

And it was because of the abuse of the horses used in the charge itself, and the damaging publicity, that The Charge of the Light Brigade was not theatrically re-released as were most Warner films at the time. The use of the “running W,” as it was called, a tethered wire which forced the animals to buckle headfirst after traveling a predetermined distance, killed and injured many horses. In fact, one stuntman was killed in a freak accident when an upended lance pierced his chest.

And it was because of the abuse of the horses used in the charge itself, and the damaging publicity, that The Charge of the Light Brigade was not theatrically re-released as were most Warner films at the time. The use of the “running W,” as it was called, a tethered wire which forced the animals to buckle headfirst after traveling a predetermined distance, killed and injured many horses. In fact, one stuntman was killed in a freak accident when an upended lance pierced his chest.

So, as Tennyson wrote——

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

A fine review of one of Errol’s best films. Yes, it’s not historically accurate, but otherwise it’s a first-rate tale of honor, sacrifice, and adventure. Errol gives a quality performance, too. I love the scene where he realizes his true love is smitten with his brother. And, as you highlighted, Steiner’s score is exceptional.

Greg,

You’ve put in a lot of work on this review. Covering the musical scores. screenwriting, the stellar cast, content. Such an interesting read on one of my favorite collaborations between Errol and Olivia. (Have to mention the adorable Nigel Bruce as well!)

Even if this film wasn’t one of the best of its genre and you don’t care for classic cinema. HELLO, Errol in that uniform is worth the price of admission. ha ha

On my list of the talented couple I would have to sandwich Charge in between Dodge City and Captain Blood. Does this even make sense?

Anyway,

A fine tribute and look back to a great film.

Have a great weekend!

Page

Page, thanks for the great comment!

[“Tedious because, for one reason, the weak-willed Elsa—a trait clearly uncharacteristic of Olivia the actress and woman—continually puts off telling Geoffrey the truth until the last moment, and as for Geoffrey’s share in all this subterfuge, he seems too dense to read her face or believe Perry’s repeated declaration. Beyond this, her preference for the dull Knowles over the full-blooded Flynn is hard to understand. “]

As a fan of Patric Knowles, I never considered him dull. He may not have been as flamboyant as Flynn, but he was far from dull. And I never could understand why Elsa would want to marry Geoffrey, who seemed more enamored of his profession than he was of her.

I think the charge itself is the best action sequence in the history of the movies.