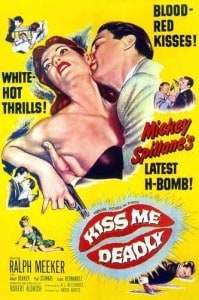

Blood red kisses! White hot thrills! Mickey Spillane’s latest H-bomb!

If you’re watching Kiss Me, Deadly for the first time, it will not be what you think. Sure, it’s one of the earliest of the Mike Hammer movies, the first being I, the Jury with Biff Elliot as Mickey Spillane’s hard-nosed private eye, and, true, there’s enough skulking, falling down stairs, muggings, knifings and killings to satisfy any modern detective aficionado. But the film, whose hard film noir look belies its three-week shooting schedule, becomes quite something else by the time of the climax—in fact, its plot, last minute like, has turned an unexpected corner.

Yes, this particular private eye film is something more . . . no, not “more” . . . something else. Something far more terrifying—and most portentous of things to come, what most sensible people, many of them properly frightened, were worrying about in the mid-’50s when Kiss Me, Deadly was made. Some lines toward the end where the film veers off course a little and first hints that it is, after all, a mutation, an aberration, a cross-fertilization of film genres:

“They’re harmless words,” says police Lieutenant Pat Murphy (Wesley Addy) to Hammer (Ralph Meeker). “Just a bunch of letters scrambled together. But their meaning is very important. Try to understand what they mean: ‘Manhattan Project.’ ‘Los Alamos.’ ‘Trinity.’ ”

Throughout the film, Hammer, this Los Angeles private dick so out for himself and such a user of others, has failed to heed his friend’s warnings, for he wants something out of it, whatever “it” is—and it must be something big if the FBI is involved. Even then, when the damage has been done and it’s too late, Murphy’s parting words, same scene, don’t sunk in: “What’s likely to happen to [your girl]? . . . Do you think you’d have done any different if you had known?”

In Mike’s case, certainly not.

Contradicting his sleek suits, array of sports cars and high class apartment, this guy, this Mike Hammer, is really a cruel, mechanical being, emotionally empty inside—empty of any real love for his women, compassion toward humanity in general or a sense of fair play among either friends or enemies. What’s it matter? Friends, enemies—they’re the same. When his lover says, “I’m always glad when you’re in trouble, ’cause then you come to me,” it’s clearly an overestimate of the man’s generosity and empathy. Hammer brutally, if that’s a strong enough word, assails a man who is following him, sending him rolling down a flight of concrete stairs, and with smiling delight crunches a man’s (Percy Helton) hand in a desk drawer to solicit information.

Contradicting his sleek suits, array of sports cars and high class apartment, this guy, this Mike Hammer, is really a cruel, mechanical being, emotionally empty inside—empty of any real love for his women, compassion toward humanity in general or a sense of fair play among either friends or enemies. What’s it matter? Friends, enemies—they’re the same. When his lover says, “I’m always glad when you’re in trouble, ’cause then you come to me,” it’s clearly an overestimate of the man’s generosity and empathy. Hammer brutally, if that’s a strong enough word, assails a man who is following him, sending him rolling down a flight of concrete stairs, and with smiling delight crunches a man’s (Percy Helton) hand in a desk drawer to solicit information.

The search for the elusive pot of gold, the elixir that will satisfy all wants and greeds, isn’t unique to Kiss Me, Deadly, or to any other film. Alfred Hitchcock’s so-titled McGuffin is ever-present in “search” films. In The Maltese Falcon, it’s the pursuit of what proves to be a worthless statue, a fake. In Kiss Me, Deadly, the thugs, pimps, molls, mobsters, the down-on-their-luckers and, yes, that wayward detective, are after something they don’t even know what it is; they only know it’s the reason for their existence.

What Hammer is after, what everybody else is after, what is called by one of the characters “the Great Whatsit,” the McGuffin in this case, is indeed nuclear, the radioactivity contained in a metal box, hot to the touch, encased in a leather container secured with straps, like a square suitcase. When the metal box is opened, as Hammer foolishly does at one point, a brilliant light shines out. A cure for cancer? The Second Coming? Not quite. When fully energized, this force growls, even screams, like the monster in a science fiction or horror flick—thus this bleed-through from another film genre in the mix that makes up Kiss Me, Deadly.

What Hammer is after, what everybody else is after, what is called by one of the characters “the Great Whatsit,” the McGuffin in this case, is indeed nuclear, the radioactivity contained in a metal box, hot to the touch, encased in a leather container secured with straps, like a square suitcase. When the metal box is opened, as Hammer foolishly does at one point, a brilliant light shines out. A cure for cancer? The Second Coming? Not quite. When fully energized, this force growls, even screams, like the monster in a science fiction or horror flick—thus this bleed-through from another film genre in the mix that makes up Kiss Me, Deadly.

With the opening titles, there’s an immediate, unsettling hint that things might be out of kilter here: the credits roll backwards, downward! However they are read, the director is Robert Aldrich (The Dirty Dozen, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?), screenwriter Turkish-born A. I. Bezzerides, cinematographer Ernest Laszlo (Stalag 17, Ship of Fools), set designer Howard Bristol, art director William Glasgow and composer Frank De Vol. So dramatic and compelling are the visuals that the score, even the frequent classical source music, seems of secondary importance.

Aside from the surprise plot twist, the film, though not fully appreciated until the ’70s, is best known for the full distillation of film noir, even an impetus for the French and their nouvelle vague. Along with the sharp black-and-white contrasts, the star of the film is Laszlo’s camera: an overhead shot from behind an arched, brick doorway; the crisscrossing of stairs in a tight, claustrophobic labyrinth; a low viewpoint when thugs rise from their chairs to settle a score with the detective; the dollying shot from behind a phonograph console and a table, with wash scattered along a clothesline, adding a sinister perspective; another dolly as a sauntering Hammer munches on popcorn and sees the thug following him reflected in a mirror; a shot from behind a metal-posted bed with a stack of suitcases partially concealing the woman in it; a tilted shot of the ceiling with a stark, single-bulb chandelier.

Aside from the surprise plot twist, the film, though not fully appreciated until the ’70s, is best known for the full distillation of film noir, even an impetus for the French and their nouvelle vague. Along with the sharp black-and-white contrasts, the star of the film is Laszlo’s camera: an overhead shot from behind an arched, brick doorway; the crisscrossing of stairs in a tight, claustrophobic labyrinth; a low viewpoint when thugs rise from their chairs to settle a score with the detective; the dollying shot from behind a phonograph console and a table, with wash scattered along a clothesline, adding a sinister perspective; another dolly as a sauntering Hammer munches on popcorn and sees the thug following him reflected in a mirror; a shot from behind a metal-posted bed with a stack of suitcases partially concealing the woman in it; a tilted shot of the ceiling with a stark, single-bulb chandelier.

Kiss Me, Deadly begins when Hammer, in his sports car, picks up along the highway Christina Bailey (Cloris Leachman in her film debut), dressed only in a trench coat—and talking in abstractions, including one riddle: “Get me to that bus stop and forget you ever saw me. If we don’t make it to the bus stop, . . . remember me.” A riddle at the time—yes, but Hammer doesn’t realize it, not being a poet or knowing anything about poetry, or the aesthetic, for that matter. He thinks nothing of it. Wrong: he should have!

Before either occupant can reach a bus stop, the car is run off the road by some thugs, Hammer knocked unconscious and Christina tortured to death—only her hanging naked legs are seen, at first shaking, then motionless. The thugs’ boss is shown, as he will be throughout most of the film, dressed in a pinstriped suit and from the shoulders down, usually from the back, more often just his lower legs and a pair of ever-walking wingtip shoes with stark, white sole stitching.

Before either occupant can reach a bus stop, the car is run off the road by some thugs, Hammer knocked unconscious and Christina tortured to death—only her hanging naked legs are seen, at first shaking, then motionless. The thugs’ boss is shown, as he will be throughout most of the film, dressed in a pinstriped suit and from the shoulders down, usually from the back, more often just his lower legs and a pair of ever-walking wingtip shoes with stark, white sole stitching.

The hoodlums put Hammer and Christina’s body in the car and push it down a ravine. Hammer’s secretary, lover and jack-of-all-trades Velda (Maxine Cooper, also in her film debut) tells him at the hospital that Christina is dead.

It’s at this point that Murphy warns the detective to stay away from this case. “Mike, why don’t you tell us what you know, then step aside like a nice fella and let us do our job?” His response is typical: “What’s in it for me?”

Ignoring the advice and undeterred in his search for this treasure, Hammer makes the rounds of the seedy, the dark and the perverse. At an apartment he finds Lily Carver (Gaby Rodgers) lounging in bed. She claims to be Christina’s ex-roommate and wants Hammer to protect her.

Ignoring the advice and undeterred in his search for this treasure, Hammer makes the rounds of the seedy, the dark and the perverse. At an apartment he finds Lily Carver (Gaby Rodgers) lounging in bed. She claims to be Christina’s ex-roommate and wants Hammer to protect her.

Like his relations with all his women, Hammer seems indifferent to Lily and moves on, now embraced and seductively kissed by a total stranger (Marian Carr)—surely this movie is just for laughs, right?!—as he enters the estate of mobster Carl Evello (Paul Stewart) and his two hit men (Jack Elam and Jack Lambert). Evello admits that he was responsible for Hammer’s car going off the cliff and asks him, “What’s it worth to you to drag your considerable talents back to the gutter you crawled out of.” (Hammer’s aesthetic senses are presumably untroubled by the awkwardness of that sentence.)

Next, in another rundown apartment, he walks in on Carmen Trivago (Fortunio Bonanova) mimicking an aria from von Flotow’s opera Martha spinning on a record player. (Earlier, in Gaslight [1944], Bonanova had been Ingrid Bergman’s vocal teacher, only the opera was Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor.) Trivago seems of little help, so the detective leaves.

Next, in another rundown apartment, he walks in on Carmen Trivago (Fortunio Bonanova) mimicking an aria from von Flotow’s opera Martha spinning on a record player. (Earlier, in Gaslight [1944], Bonanova had been Ingrid Bergman’s vocal teacher, only the opera was Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor.) Trivago seems of little help, so the detective leaves.

While Hammer is away, his friend and car mechanic Nick (Nick Dennis) is working under a vehicle when the faceless man in the wingtips releases the car jack, crushing him.

From Hammer’s apartment, he is kidnapped by Evello’s two thugs and taken to an isolated beach house where he is tied to a bed—the third or fourth appearance of a bed, perhaps an unintentional motif. The man in the pinstriped suit administers some sodium pentothal: somebody who is searching for the same thing wants to know what Hammer knows. In a switch-a-roo found possibly only in detective yarns, Hammer is able to free his bonds and, while left alone, lure Evello into the semi-dark room and knock him out. He then imitates Evello’s voice to draw in the two thugs, saying that the hostage’s usefulness is over. Unseen by the camera, Hammer had tied Evello, face down, to the bed, and when one thug stabs Evello dead, thinking it’s Hammer, the other flees. One of the film’s most delectable sequences.

From Hammer’s apartment, he is kidnapped by Evello’s two thugs and taken to an isolated beach house where he is tied to a bed—the third or fourth appearance of a bed, perhaps an unintentional motif. The man in the pinstriped suit administers some sodium pentothal: somebody who is searching for the same thing wants to know what Hammer knows. In a switch-a-roo found possibly only in detective yarns, Hammer is able to free his bonds and, while left alone, lure Evello into the semi-dark room and knock him out. He then imitates Evello’s voice to draw in the two thugs, saying that the hostage’s usefulness is over. Unseen by the camera, Hammer had tied Evello, face down, to the bed, and when one thug stabs Evello dead, thinking it’s Hammer, the other flees. One of the film’s most delectable sequences.

Velda, obviously more intuitive than her boss, connects Christina’s parting words about “remember me” to a line from Christina Rossetti’s poem “Remember”: “For if the darkness and corruption leave/A vestige of the thoughts that once I had . . . ” Even if one of the more obscure lines from the poem, it’s apparently the clue to everything—just how isn’t made clear. Note the identical first names, Miss Bailey’s and poetess Rossetti’s.

Soon after, Velda is kidnapped by the pinstriped-suit guy.

Hammer tracks down a key to a gym locker, and, inside, the square, leather suitcase. He unfastens the straps and partially opens the metal box inside. A brilliant, white light shines out, burning his wrist. He quickly closes it. The suitcase is later stolen and a man killed.

Hammer tracks down a key to a gym locker, and, inside, the square, leather suitcase. He unfastens the straps and partially opens the metal box inside. A brilliant, white light shines out, burning his wrist. He quickly closes it. The suitcase is later stolen and a man killed.

The climax occurs at the beach house. Turns out, Lily is actually Gabrielle, in cahoots with Dr. Soberin (Albert Dekker), the man in the pinstriped suit and wingtips. With Velda locked in a nearby room, Soberin is preparing to leave with the box. What he plans to do with it—what he can do with it—is a mystery in itself. Gabrielle wants her share of what’s in the box, if not all of its contents.

“The head of Medusa—that’s what’s in the box,” he warns her. “And [he] who looks on her will be changed, not into stone, but into brimstone and ashes.” He even warns her of the fate of Lot’s wife, but Gabrielle, like most people in this sordid tale, wants it all, whatever it is, and shoots Soberin.

“The head of Medusa—that’s what’s in the box,” he warns her. “And [he] who looks on her will be changed, not into stone, but into brimstone and ashes.” He even warns her of the fate of Lot’s wife, but Gabrielle, like most people in this sordid tale, wants it all, whatever it is, and shoots Soberin.

Just then Hammer enters. With the gun pointed at him, Gabrielle says, “Kiss me, Mike. . . . The liar’s kiss that says ‘I love you.’ You’re good at giving such kisses. Kiss me.” Before he can do so, even if she had really wanted a kiss in the first place, she shoots him. He falls to the floor.

She unstraps the outside box, then opens the metal one—the lid wide open now, releasing the full, terrible capacity of the nuclear energy. Screaming, she is immediately engulfed by the fire, the heat, the flames, continuing, in fact, to scream long after, technically, she would have been instantly incinerated.

Mike lifts himself from the floor, presumably wounded, and frees Velda. Together, they stumble down to the beach as the beach house catches fire, now emitting a growling sound. As they trudge into the surf, the building explodes, not quite in a vertical mushroom cloud—the producers stopped short of being that obvious—but the explosion has to illumine all of Los Angeles.

Mike lifts himself from the floor, presumably wounded, and frees Velda. Together, they stumble down to the beach as the beach house catches fire, now emitting a growling sound. As they trudge into the surf, the building explodes, not quite in a vertical mushroom cloud—the producers stopped short of being that obvious—but the explosion has to illumine all of Los Angeles.

In some subsequent releases of Kiss Me, Deadly, unknown to director Aldrich, the film ends with the beach house exploding before Hammer and Velda are seen escaping. Either way, the message is the same: the two are doomed, as is all of the nearby city, and a good deal of the countryside beyond, possibly a great deal more.

Great review of one of my favorite films. Thank you. Aldrich made one of the best ever noirs with Kiss Me Deadly.

Love this film and enjoyed your review much.

A very good review of a noir classic. You’re right–there’s nothing quite like it. I was never a Ralph Meeker fan, but he was excellent as Hammer. Somehow, Aldrich brought out the best in him. And as for that ending, it’s a doozy and left me wondering what the heck I just watched.

Have not seen this movie in a dog’s age. It’s scheduled on TV this evening and I can back up the viewing with your thoughtful article. Well done, and thanks.