“You’re like a leaf that the wind blows from one gutter to another.” — Jeff Bailey to Kathie Moffat

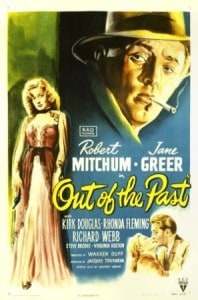

To even begin to convey the plot of Out of the Past (1947) is a challenge, so convoluted is it. But complexity, even ambiguity, is a trait, one could say a necessary and primary ingredient, of the film noir, and this film is one of the finest examples—dark, cold and steely. Beyond that convolution, the genre is characterized by lonely, desperate people up against desperate odds beyond their control, usually brought on by themselves; a femme fatale bound to a strong male protagonist; a voice-over narration, often in documentary style; dark, shadowy cinematography; and much time spent at night and in the cruel alleys, hotels, bars and nightclubs of the big city.

Along with jazz, film noir is one of the few original artistic creations America has given the world. Clearly, the transferred Broadway musical notwithstanding, film noir is the greatest innovation to come from Hollywood.

The RKO picture Out of the Past, like so many noir films of the ’40s, comes with a team of certified artists, artists that brilliantly justify their credentials in this particular genre and in this specific film, polished and scrubbed clean, “clean” here being a relative term. For, not to be counted as a negative—no, certainly not in a film noir—the bodies abound, the shadows nearly overcome and the end, as ordained from the fateful beginning, resolves things with that negative, downward turn. Like hitting a brick wall.

The director, Jacques Tourneur, born in Paris, first gained world attention with two innovative horror films, one after the other, Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie, and would return to the horror genre with Curse of the Demon toward the end of his career. Out of the Past, the first of his noir films, would be followed by Nightfall and Berlin Express. Though generally unlisted among the truly great noir directors, such as Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Robert Siodmak and Edward Dmytryk, among many others, Tourneur deserves to be on that list, if only for Out of the Past.

Italian cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca, who photographed Cat People, is credited with many more noir films than Tourneur, including Stranger on the Third Floor, The Seventh Victim, Deadline at Dawn, Roadblock and Clash by Night. He is versatile in both interiors and exteriors, as easily proven in Out of the Past, since, uncharacteristic of the genre, the film contains a high proportion of exterior scenes—woods, lakes and mountains—and even opens in the deceptive serenity of a pastoral setting.

Italian cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca, who photographed Cat People, is credited with many more noir films than Tourneur, including Stranger on the Third Floor, The Seventh Victim, Deadline at Dawn, Roadblock and Clash by Night. He is versatile in both interiors and exteriors, as easily proven in Out of the Past, since, uncharacteristic of the genre, the film contains a high proportion of exterior scenes—woods, lakes and mountains—and even opens in the deceptive serenity of a pastoral setting.

With the help of the sophisticated eye of Musuraca, Tourneur takes along with him that “other character” in the film, the viewer. He takes him on a surreal odyssey from the bright, deceptively optimistic opening through the depths of darkness and human misery, turning the black and white screen into something like an Edward Hopper etching, framing the many night scenes in shadow and still more shadow, and out again into the bright light of day, so much of a contrast that it seems to hurt the eyes. What is seen on screen is often symbolic, a rubbing off on the viewer, of the characters’ dilemma and anguish, the old cliché, here as a terrible reminder, that one can’t escape the past.

Perhaps the most unsung of the artists who worked on Out of the Past is composer Roy Webb, tragically unsung in that he made far more important, sometimes great, contributions than most critics have acknowledged, or even been astute enough to sense. As versatile an artist as Musuraca is in his field, Webb scored all varieties of movies, but made his mark in horror films—he scored Tourneur and Musuraca’s Cat People—and film noirs that include Clash by Night, Stranger on the Third Floor, The Window, Murder, My Sweet,Crossfire, Where Danger Lives and also Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious. The British director is not generally seen as a noir genius, so distracted are critics and audiences by his title of “master of suspense.”

Perhaps the most unsung of the artists who worked on Out of the Past is composer Roy Webb, tragically unsung in that he made far more important, sometimes great, contributions than most critics have acknowledged, or even been astute enough to sense. As versatile an artist as Musuraca is in his field, Webb scored all varieties of movies, but made his mark in horror films—he scored Tourneur and Musuraca’s Cat People—and film noirs that include Clash by Night, Stranger on the Third Floor, The Window, Murder, My Sweet,Crossfire, Where Danger Lives and also Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious. The British director is not generally seen as a noir genius, so distracted are critics and audiences by his title of “master of suspense.”

Webb’s screen presence in less dramatic, less broadly upfront, more of a subdued bystander to the emotion and action, than the stronger personalities of his contemporaries, say, Franz Waxman or that greatest of all film noir composers, Miklós Rózsa. More so than Webb, Rózsa had the good fortune to score a much higher percentage of major films—Double Indemnity, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers,The Killers, The Red House, Brute Force, The Naked City, Kiss the Blood Off My Hands and The Asphalt Jungle.

Webb was fond of the string tremolo and trill, even to the point of parody, an undoubted carryover from his horror film experience, so much so that a musical montage in Out of the Past might recall a similar one in Notorious or The Window. But, as Christopher Palmer has written so perceptively, “he had a special feeling for atmospheric nuance and . . . employed mutedly dissonant harmonic color and sparely evocative texture to great effect.”

Webb was fond of the string tremolo and trill, even to the point of parody, an undoubted carryover from his horror film experience, so much so that a musical montage in Out of the Past might recall a similar one in Notorious or The Window. But, as Christopher Palmer has written so perceptively, “he had a special feeling for atmospheric nuance and . . . employed mutedly dissonant harmonic color and sparely evocative texture to great effect.”

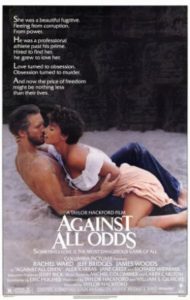

If this composer’s understated style has a flaw, it’s that the lyrical melodies, as the main one in Out of the Past, are appropriate to the moment and support the screen admirably, but fall easily out of the memory. In Against All Odds (1984), an over-long and bloated, careless remake of Out of the Past, Phil Collins wrote and sings the film’s title song, “Against All Odds (Take a Look at Me Now),” showing what can be done to create a melody that matches the noir ambiance and that persists in the memory.

The Out of the Past screenplay is by Daniel Mainwaring under the pseudonym of Geoffrey Homes, from his novel Build My Gallows High, the title given to the film’s release in Britain. Mainwaring is assisted by James M. Cain (author of The Postman Always Rings Twice, Mildred Pierce) and Frank Fenton (screenwriter on River of No Return, Garden of Evil). The resultant script chisels and fine-tunes the typical noir dialogue to the sharpest, bitterest conceivable.

The Out of the Past screenplay is by Daniel Mainwaring under the pseudonym of Geoffrey Homes, from his novel Build My Gallows High, the title given to the film’s release in Britain. Mainwaring is assisted by James M. Cain (author of The Postman Always Rings Twice, Mildred Pierce) and Frank Fenton (screenwriter on River of No Return, Garden of Evil). The resultant script chisels and fine-tunes the typical noir dialogue to the sharpest, bitterest conceivable.

Under careful analysis, the noir language is more than just a little stilted and unnatural—but how it seems so appropriate to the characters, how it mesmerizes, how it has held audiences fascinated for generations by its cold poetry and sardonic toughness. In any number of scenes, there aren’t just one or two rejoinders between combatants, as it were, but, more often, certainly in Out of the Past, the banter seems unending, in biting rapid fire torrents, unnatural as hell, as if, “Jeez, this vernacular has to be from a script! People don’t normally talk this way!”

Here is an exchange between the two principals in their second meeting:

“I’ve been sitting here for three hours. . . . ” Jeff Bailey says.

“You know, you’re a curious man,” Kathie Moffat says.

“You’re gonna make every guy you meet a little bit curious.”

“That’s not what I mean. You don’t ask questions. You don’t even ask me what my name is.”

“All right. What’s your name?”

“Kathie.”

“I like it.”

“Or where I come from.”

“I’m thinking about where we’re going.”

“Don’t you like it in here?”

“I’m just not ready to settle down.”

“Shall I take you somewhere else?”

“You’re gonna find it very easy to take me anywhere.”

“You know, I’m a much better guide than José Rodriguez [a local who, moments before, had offered to guide the couple aroundAcapulco]. Wanna try me?”

“That isn’t the way to play.”

“Why not?”

“Because it isn’t the way to win.”

“Is there a way?”

“There’s a way to lose more slowly.”

And as an introduction to this scene, Jeff’s narration is as cold and detached as the dialogue:

“You don’t get vaccinated for Florida, but you do for Mexico. So I just followed that pounds of excess baggage to Mexico City. She had been at the Refoma [hotel] and then gone. I took the bus south like she did. It was hot in Taxco. . . . She had to wind up here, because if you wanna go south, here’s where you get the boat. All I had to do was wait. Near the plaza was a little café called La Mar Azul, next to a movie house. I sat there in the afternoons and drank beer. I used to sit there half asleep with a beer and the darkness, only that music from the movie next door kept jarring me awake. And then I saw her coming out of the sun, and I knew why Whit didn’t care about that forty grand.”

Note the poetic “ . . . I saw her coming out of the sun . . . ”; later it would become “She waited until it was late . . . and then she walked in out of the moonlight, smiling.”

So impressive are the elements of direction, music and screenplay in Out of the Past, it’s unusual, this late, to begin discussing the stars, primarily the two who fit so well into the milieu of this film, its dialogue and visual persuasions.

Robert Mitchum had made over thirty earlier films without drawing much attention, except perhaps for The Story of G.I. Joe and some noirs such as Crossfire, directed by Edward Dmytryk, and When Strangers Marry, directed by William Castle. Mitchum made nineteen films in 1943 alone. The role of Jeff Bailey in Out of the Past established, once and for all, the Mitchum image as a laconic, underacting, slow-moving but graceful man, who seemed to do nothing during filming, yet, like Gary Cooper, everything was there on screen. He came from no acting school and left no heirs, even if that were possible.

Robert Mitchum had made over thirty earlier films without drawing much attention, except perhaps for The Story of G.I. Joe and some noirs such as Crossfire, directed by Edward Dmytryk, and When Strangers Marry, directed by William Castle. Mitchum made nineteen films in 1943 alone. The role of Jeff Bailey in Out of the Past established, once and for all, the Mitchum image as a laconic, underacting, slow-moving but graceful man, who seemed to do nothing during filming, yet, like Gary Cooper, everything was there on screen. He came from no acting school and left no heirs, even if that were possible.

The image seen on screen, especially from Out of the Past onward, is a large part of the man Robert Mitchum really was, though he was a complicated, multifaceted person, so often boorish but sometimes generous and sensitive as well, a portrait clearly beyond the confines of these pages. An excellent and objective source for the real man is the biography by Lee Server, Robert Mitchum, “Baby, I Don’t Care” (2001).

His co-star in Out of the Past is Jane Greer as the scheming, duplicitous Kathie Moffat, seeming content with whichever of two men she is with, willing to play one against the other, though loving, in her fashion, only Jeff. Greer was familiar with the wiles of men, not only with the two in the film, but with the possessive Howard Hughes, who broke up her six-month marriage to crooner Rudy Vallee. “Howard Hughes was obsessed with me,” she said, “but at first it seemed as if he were offering me a superb career opportunity.” She would appear with Mitchum in another film noir of sorts, The Big Deal (1949), directed by Don Siegel, and, incidentally, would play the mother of Kathie in the Against All Odds remake.

After a brief fanfare, Roy Webb’s main title music sets a congenial, even happy mood, little suggesting what is to follow—any more than does the bright photography and airy setting.

After a brief fanfare, Roy Webb’s main title music sets a congenial, even happy mood, little suggesting what is to follow—any more than does the bright photography and airy setting.

Jeff Bailey (Mitchum) is quite content to live in Bridgeport, California, run a gas station and court girlfriend Ann (a much subdued, close to bland Virginia Huston), and try to forget his past. While fishing with her, he sees, on a distant knoll, his deaf friend, “The Kid” (Dickie Moore), signal some kind of warning.

Soon a man, dressed appropriately in black, appears. Joe Stefanos (Paul Valentine) tells Jeff that an old friend, Whit Sterling (Kirk Douglas in his second film, the first being The Strange Love of Martha Ivers), wants to see him. Feeling compelled by the inevitable, Jeff agrees to go. This is film noir, where Fate is omnipresent and the characters, and the audiences for that matter, never question motivations or plots.

Soon a man, dressed appropriately in black, appears. Joe Stefanos (Paul Valentine) tells Jeff that an old friend, Whit Sterling (Kirk Douglas in his second film, the first being The Strange Love of Martha Ivers), wants to see him. Feeling compelled by the inevitable, Jeff agrees to go. This is film noir, where Fate is omnipresent and the characters, and the audiences for that matter, never question motivations or plots.

Before leaving, he explains to Ann that his real name is Jeff Markham, that he and his partner Jack Fisher (Steve Brodie) once worked for Sterling as private detectives, so to speak. Thus begins a series of flashbacks of Jeff’s dark past. Back when, he tells Ann, he and Whit greet one another like two old friends, but their wariness is quite apparent. Whit says his girlfriend Kathie Moffat (Greer) shot him and took $40,000. He wants her back. For Jeff’s trouble, $5,000 now and the same when he returns her.

Discovering that she has headed for Acapulco, Jeff arrives ahead of her. He finds her rather easily and they begin a romance. In a variation on the romping-through-the-heather preface to romantic consummation, the two rush through the rain to her place, take turns drying each other’s hair with a towel, complete with laughter and pretended resistance; then he throws the towel at the lamp, which falls over and goes out. The wind blows open the front door . . . and, with the lovers unseen on screen, this, the days of heavily censoredHollywood, the audience’s imagination must take over.

Discovering that she has headed for Acapulco, Jeff arrives ahead of her. He finds her rather easily and they begin a romance. In a variation on the romping-through-the-heather preface to romantic consummation, the two rush through the rain to her place, take turns drying each other’s hair with a towel, complete with laughter and pretended resistance; then he throws the towel at the lamp, which falls over and goes out. The wind blows open the front door . . . and, with the lovers unseen on screen, this, the days of heavily censoredHollywood, the audience’s imagination must take over.

While Kathie happens to be “out,” Whit and Stefanos surprise Jeff at the front door, wondering why the delay in reporting back on his woman hunt. Jeff tells Whit she simply got away. There are several suspenseful moments as Jeff quickly removes from the room evidence of her presence; he spots a look-alike woman, complete with a similar white sunhat and, later, signals Kathie to lay low. Whit leaves, telling Jeff he still wants Kathie back.

While Kathie happens to be “out,” Whit and Stefanos surprise Jeff at the front door, wondering why the delay in reporting back on his woman hunt. Jeff tells Whit she simply got away. There are several suspenseful moments as Jeff quickly removes from the room evidence of her presence; he spots a look-alike woman, complete with a similar white sunhat and, later, signals Kathie to lay low. Whit leaves, telling Jeff he still wants Kathie back.

Even well aware of why Jeff is here, she is captivated by him and urges they run away together. Now in San Francisco, they become as inconspicuous as possible, but are spotted by Fisher. The two lovers think they are safe in a cabin in the woods. When Fisher shows up and demands money to keep quiet, the two men fight and Kathie shoots the blackmailer. With the camera on the surprised Jeff, the sound alone of a departing car conveys that Kathie has high-tailed it. Jeff, now left to dispose of the body, finds in her bankbook a deposit of $40,000.

Back to the present now. Answering Whit’s call to see him, Jeff arrives at his palatial estate on Lake Tahoe and finds Kathie, who, during the intervening years, has returned to Whit. Whit wants him to purloin from his lawyer, Leonard Eels (Ken Niles), a document that shows his million-dollar tax dodge. Eels is blackmailing him with it.

Back to the present now. Answering Whit’s call to see him, Jeff arrives at his palatial estate on Lake Tahoe and finds Kathie, who, during the intervening years, has returned to Whit. Whit wants him to purloin from his lawyer, Leonard Eels (Ken Niles), a document that shows his million-dollar tax dodge. Eels is blackmailing him with it.

Leery of Whit, Jeff visits Eels’ office to warn him. Earlier, he had met his secretary, Meta Carson (Rhonda Fleming), a conniving double of Kathie, who helps him steal the tax report. When Jeff returns later to the office, he finds Eels dead. He hides the body in a closet and steals the sought-after document.

While Jeff is back in Bridgeport—still in the present—Stefanos, on orders from Kathie, sets out to kill Jeff, hoping “The Kid” will lead him to his prey. “The Kid” heads for a fishing hole where Jeff is hiding out, and sees Stefanos on a bluff, taking aim at Jeff. With a toss of his fishing line, he snags Stefanos’ clothes with the hook, pulling him off balance, sending him falling to his death.

While Jeff is back in Bridgeport—still in the present—Stefanos, on orders from Kathie, sets out to kill Jeff, hoping “The Kid” will lead him to his prey. “The Kid” heads for a fishing hole where Jeff is hiding out, and sees Stefanos on a bluff, taking aim at Jeff. With a toss of his fishing line, he snags Stefanos’ clothes with the hook, pulling him off balance, sending him falling to his death.

Jeff returns to Lake Tahoe to warn Whit of Kathie’s treachery. Whit thinks he should turn her over to the police for the murder of Fisher. When Jeff returns later to Whit’s place, he finds Kathie has killed him. She gives him a choice, either run away with her or take the blame for Whit’s murder (which brings the film’s dead total to four), though just how she will incriminate him isn’t made clear.

Again it’s Fate, against which these characters have little resistance—or desire to resist. So Jeff agrees to go with her, but he first makes a secret phone call before they leave. When they drive up the road, the police are waiting. Realizing Jeff has betrayed her, she shoots him and, under police fire, the car crashes. Both occupants are dead.

Again it’s Fate, against which these characters have little resistance—or desire to resist. So Jeff agrees to go with her, but he first makes a secret phone call before they leave. When they drive up the road, the police are waiting. Realizing Jeff has betrayed her, she shoots him and, under police fire, the car crashes. Both occupants are dead.

The film’s brief coda returns to the sunlit atmosphere of the opening. Ann asks “The Kid” if Jeff had lied about running off with Kathie. He nods “yes.”

If the film noir had reached its high point in the ’40s and early ’50s, it was by no means dead. Far from it. Perhaps the true spirit of the genre had been blunted—there would never again be the novelty of those first films or the unique influences of World War II and the immediate post-war era—but directors still attempted to recapture its spirit, even seeking new perspectives, in what might be called neo-noir.

Jack Smight’s Harper (1966) features a laid back Paul Newman, who was perhaps influenced by the apathetic Mitchum. The Long Goodbye (1973), its weaknesses offset by John Williams’ tongue-in-cheek score, displays more than a bit of satire and reveals director Robert Altman’s lack of an understanding of the film noir soul. Quite differently, Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974) is one of the best of the post-’50s noirs, even if realized with few shades and shadows.

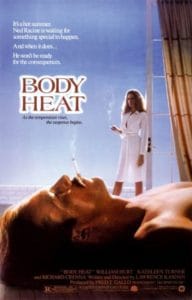

Lawrence Kasdan’s steamy Body Heat (1981) is mostly about the hot body temperatures shared by William Hurt and Kathleen Turner in a woman-wants-husband-killed rip-off of Double Indemnity. Blood and violence are carried a few steps further in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) in a number of overlapping stories—talk about convoluted! Even more so, Michael Winterbottom’s sadistic The Killer Inside Me (2010) would seem to carry brutality and mayhem to the ultimate, returning to the early ’50s for the goings-on in a small Texastown and a psychotic killer hidden in the unlikeliest of individuals.

Lawrence Kasdan’s steamy Body Heat (1981) is mostly about the hot body temperatures shared by William Hurt and Kathleen Turner in a woman-wants-husband-killed rip-off of Double Indemnity. Blood and violence are carried a few steps further in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) in a number of overlapping stories—talk about convoluted! Even more so, Michael Winterbottom’s sadistic The Killer Inside Me (2010) would seem to carry brutality and mayhem to the ultimate, returning to the early ’50s for the goings-on in a small Texastown and a psychotic killer hidden in the unlikeliest of individuals.

The film noir, then, has indeed evolved into some strange and almost unrecognizable mutations since Fritz Lang’s first American movie and possibly the first of all the film noirs, Fury in 1936.

Great article. I love all the principal leads in this, but especially Kirk Douglas. His Sterling is both charming and vile. As for Mitchum, he was such a good noir actor.

Although I am posting the comment, the below came from reader Vance Durgin and I thought it was well worth sharing.

Good post, however I think you were a little unfair to Webb regarding the score: “If this composer’s understated style has a flaw, it’s that the lyrical melodies, as the main one in Out of the Past, are appropriate to the moment and support the screen admirably, but fall easily out of the memory.”

I see this mistake all the time on various classic movie blogs that assume that the main ‘Past’ melody was written for the movie. It wasn’t and it wasn’t written by Webb. It’s from a pop tune called ‘The First Time I Saw You,’ from the 1937 RKO movie ‘The Toast of New York.’ That RKO owned the rights helps explain its use in ‘Past’ (‘Past’ also uses an instrumental version of another pop tune from an earlier RKO film, ‘Step Lively,’ in the scene where Mitchum snags Whit’s files from the nightclub manager. That same track turns up later in RKO’s ‘The Racket,’ so the studio liked to economize on scores).

I’d argue that ‘The First Time I Saw You,’ instead of falling out of memory, likely was remembered by 1947 audiences and is an early example of using an ‘oldie’ to invoke a mood. Like Steiner’s (forced) use of ‘As Time Goes By’ in ‘Casablanca.’ And the lyrics underscore Mitchum’s ‘first sight’ attraction to Greer, which further supports its use in the movie, though the fact that cash-strapped RKO already owned the rights likely was the bigger factor.

Jimmie Lunceford’s 1930s recording of the song:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MIChYQkx5I