“We live in an age of mediocrity. Stars today are not the same stature as Bogie, James Cagney, Spencer Tracy, Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart.” — Lauren Bacall

“We live in an age of mediocrity. Stars today are not the same stature as Bogie, James Cagney, Spencer Tracy, Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart.” — Lauren Bacall

Nicknames and titles for movies stars, especially for the women, were once a part of Hollywood glamour, which now has descended to sexual notoriety—the more sensational and salacious the better. Back in the ’30s and ’40s, a high time for real glamour, there was “The ‘It’ Girl,” the “Blonde Bombshell” and all varieties of other “girls”—the “Pin-Up,” the “Peek-a-Boo,” the “Sweater” and the “Oomph” Girl. If you’re too old to remember, they were, respectively, Clara Bow, Jean Harlow, Betty Grable, Veronica Lake, Lana Turner and Ann Sheridan.

And then there was that girl with “The Look.”

Betty Joan Perske was born on September 16, 1924, in New York City. She changed her professional name to Lauren Bacall. When director Howard Hawks said her voice was “a little thin, reedy,” she artificially lowered it by reading aloud Lloyd C. Douglas’ The Robe. Before exiting a room in her film début in To Have and Have Not (1944), she lowered her chin and looked up at her co-star from under her brow—thus the beginning of “The Look.” So, with the husky voice, the cat-like green eyes, the tall, slender figure and, now, “The Look”—a totally original and fascinating woman had appeared on screen. Unique in Hollywood. And an overnight sensation.

Lauren Bacall, always known as Betty, died August 12, 2014, age 89, in the city where she was born. At the time, and perhaps still, her passing unfortunately became a second act of sorts, overshadowed by the deaths, at about the same time, of two perhaps better known stars, one clearly more actively in the public’s mind—Robin Williams and James Garner. A guarded phrase, one that can’t be used much longer, she passes as one of the “last stars of Hollywood’s golden age.” Garner, starting his career some eight years later, just missed being a part of that epoch.

Bacall’s co-star in her To Have and Have Not début was Humphrey Bogart, twenty-four years her senior. No matter. The single, nineteen-year-old starlet immediately began an affair with him, then in an unhappy marriage, his third, to actress Mayo Methot. When “Bogie,” which she always said was correct, not “Bogey,” received his divorce, they were married eleven days later. Two children, a boy and a girl, and over twenty more pictures later, Bogart died two weeks into the new year, 1957. His horrific but courageous battle against throat cancer is vividly and clinically described by Bacall in her autobiography By Myself and its later, but perhaps unnecessary post-1978 update, By Myself and More.

Bacall’s co-star in her To Have and Have Not début was Humphrey Bogart, twenty-four years her senior. No matter. The single, nineteen-year-old starlet immediately began an affair with him, then in an unhappy marriage, his third, to actress Mayo Methot. When “Bogie,” which she always said was correct, not “Bogey,” received his divorce, they were married eleven days later. Two children, a boy and a girl, and over twenty more pictures later, Bogart died two weeks into the new year, 1957. His horrific but courageous battle against throat cancer is vividly and clinically described by Bacall in her autobiography By Myself and its later, but perhaps unnecessary post-1978 update, By Myself and More.

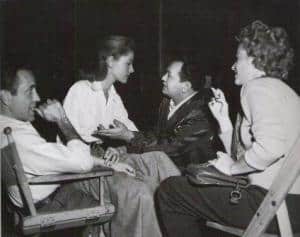

But before the initial diagnosis of the disease, in their short eleven years together, the couple were the toast of Hollywood and rumored to have an ideal marriage, one of few in Tinsel Town, though it wasn’t entirely that: they did have their disagreements and fights. Besides being well-liked among a large majority of the Hollywood set, Bogie and Betty made friends with many diverse and illustrious people—Margot Fonteyn, Ernest Hemmingway, Adlai Stevenson, T. S. Eliot, Leonard Bernstein, John O’Hara, even Harry Truman (sitting on his piano in a famous photo). “I still can’t believe the people I met—from friends we made and kept,” Bacall wrote in By Myself. “It was incredible to me that at twenty-six I was meeting the best in so many worlds.”

Bogart’s film reputation, liberated from the gangster roles of the ’30s, which always left him dead at film’s end, was vitalized with the successes of The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca, even more so when sparks flew in the four films he made with Bacall, between 1944 and 1948. So short a time, yet viewing these films over the years, we feel as if the two had been starring together for most of their, and our, lives.

Bogart’s film reputation, liberated from the gangster roles of the ’30s, which always left him dead at film’s end, was vitalized with the successes of The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca, even more so when sparks flew in the four films he made with Bacall, between 1944 and 1948. So short a time, yet viewing these films over the years, we feel as if the two had been starring together for most of their, and our, lives.

Despite so few films together, those sparks, that magic, made them one of the great romantic pairs of the movies, whether unmarried in that first film or married in the three thereafter. Against the later generations of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward and Woody Allen and Mia Farrow, there was, in the ’30s, the torrid, red hot chemistry between Clark Gable and Jean Harlow, and maybe a little less hot between Gable and Joan Crawford.

The sophisticated and relaxed comic banter of William Powell and Myrna Loy, playing a detective and his wife, suggested sex between them was a foregone conclusion, despite always—always!—those twin beds. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers spent their films dancing, and Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald exhausted one another by singing duets. In all but one of the eight films in which Errol Flynn and Olivia deHavilland starred as lovers, Flynn was either on a horse or a ship, though the chemistry was palpable, because they had feelings for each other off screen. Walter Pidgeon and Greer Garson, who shared eight films, seemed like they had always been married, maturing gracefully between 1941 and 1953.

Other couples—John Gilbert and Greta Garbo, Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, Woody Allen and Diane Keaton—could be romantic or sensual on different levels, or merely have innocent fun, as did Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland. But the real competitors for the unique excitement that Bogie and Bacall generated were their friends, Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn, who made nine films together, between 1942 and 1967. Except for Newman and Woodward, Tracy and Hepburn had the longest screen romance. Newman and Woodward, of the romantic couples mentioned, were the only ones married during all their films.

Other couples—John Gilbert and Greta Garbo, Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, Woody Allen and Diane Keaton—could be romantic or sensual on different levels, or merely have innocent fun, as did Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland. But the real competitors for the unique excitement that Bogie and Bacall generated were their friends, Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn, who made nine films together, between 1942 and 1967. Except for Newman and Woodward, Tracy and Hepburn had the longest screen romance. Newman and Woodward, of the romantic couples mentioned, were the only ones married during all their films.

As for those four Bogart/Bacall collaborations, how did it go over, that very first scene ever between them in that first film, To Have and Have Not? Her first line to Bogart’s character was “Anybody got a match?” She remembers: “My hand was shaking, my head was shaking, the cigarette was shaking. I was mortified. The harder I tried to stop, the more I shook. I realized that one way to hold my trembling head still was to keep it down, chin low, almost to my chest and eyes up at Bogart.” Thus “The Look.”

When it’s all boiled down, To Have and Have Not is a poor man’s Casablanca, which takes place in a corrupt backwater during World War II, and is similar in plotting, setting, Nazi nasties and intrigue, even interchangeable characters. There is the requisite fat man, Sydney Greenstreet inCasablanca, replaced by Dan Seymour, comic relief switched from S. Z. Sakall to Walter Brennan, saloon pianist Dooley Wilson supplanted byHoagy Carmichael, lounge singer Corinna Mura replaced by Bacall and so on, including even duplicate casting: not only Seymour but MarcelDalio, an exile French actor.

When it’s all boiled down, To Have and Have Not is a poor man’s Casablanca, which takes place in a corrupt backwater during World War II, and is similar in plotting, setting, Nazi nasties and intrigue, even interchangeable characters. There is the requisite fat man, Sydney Greenstreet inCasablanca, replaced by Dan Seymour, comic relief switched from S. Z. Sakall to Walter Brennan, saloon pianist Dooley Wilson supplanted byHoagy Carmichael, lounge singer Corinna Mura replaced by Bacall and so on, including even duplicate casting: not only Seymour but MarcelDalio, an exile French actor.

On the island of Martinique, Harry Morgan (Bogart) rents out his boat to fishermen and is assisted by a drunk friend (Brennan). When a customer (Walter Sande) is shot before he can pay him, Harry—Steve to his friends—is forced, by need of money, to take on a night job smuggling to the island some members of the French Resistance, a man and wife (Dolores Moran and Walter Surovy). Thus begins the intrigue portion of the film.

A subplot is Morgan’s involvement with a lounge singer, pickpocket and drifter (Bacall), who sings a few songs (“How Little We Know” and “Am I Blue?”), accompanied by Carmichael, who also has some solos on the piano (“Hong Kong Blues”). Andy Williams has written that his fourteen-year-old voice was dubbed for Bacall’s in “How Little We Know,” but she writes in By Myself that she lip-synced her own recording. She added, though, that Hawks “thought one or two notes might have to be dubbed later on.” Perhaps these dubs were Williams’ reference.

The most famous Bogart/Bacall scene in To Have and Have Not occurs about forty-five minutes into the movie. They have been free-associating and coming on to one another until, finally, she kisses him. “What did you do that for?” he asks. “I’ve been wondering if I’d like it.” “What’s the decision?” “I don’t know yet.” They kiss again. “It’s even better when you help,” she adds.

As she’s leaving, she says, “You know you don’t have to act with me, Steve. You don’t have to say anything, and you don’t have to do anything. Not a thing. Oh, maybe just whistle.” She is at the door, about to leave the room, when she turns back to Morgan. “You know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and . . . blow.”

In Bogart and Bacall’s next film, The Big Sleep (1946), once again William Faulkner is one of the script writers. The previous movie had been based on Hemmingway’s supposed worst novel, turned into something more stimulating; now The Big Sleep source is Raymond Chandler’s first novel, which introduces detective Philip Marlowe (Bogart). The confusing novel produced an equally confusing movie, with five murders, possibly a suicide. Even the author didn’t know who committed one murder.

In Bogart and Bacall’s next film, The Big Sleep (1946), once again William Faulkner is one of the script writers. The previous movie had been based on Hemmingway’s supposed worst novel, turned into something more stimulating; now The Big Sleep source is Raymond Chandler’s first novel, which introduces detective Philip Marlowe (Bogart). The confusing novel produced an equally confusing movie, with five murders, possibly a suicide. Even the author didn’t know who committed one murder.

Things begin with Marlowe’s visit to General Sternwood’s (Charles Waldron) mansion. The scene in a hothouse is especially atmospheric and claustrophobic, a small version of Violet Venable’s primordial garden in Suddenly, Last Summer. The enfeebled retired general, by the way, is given some vivid dialogue: “Nasty things [orchids]. Their flesh is too much like the flesh of men, and their perfume has the rotten sweetness of corruption.” He wants Marlowe to resolve some gambling debts owed by his nymphy daughter, Carmen (Martha Vickers). Marlowe had met her upon entering the mansion. “She tried to sit in my lap while I was standing up,” he tells Sternwood.

As he is leaving, Marlowe meets the other daughter Vivian (Bacall), who says she believes her father has really summoned him to find a friend who has disappeared a month earlier. From there the story line becomes truly complicated, with characters acting under false motives and taking credit, and discredit, for various crimes, real or imagined. Frankly, the best scenes in the film, including all the murder and mayhem, is Bogart’s visits, sans Bacall, to two book stores, in the first playing a nerdy intellectual intentionally asking for book editions that don’t exist.

Released first to the fighting men overseas, The Big Sleep was withheld from stateside release until Warner Brothers could issue its backlog of war films, now that the conflict was winding down. In the meantime, the movie was greatly revised—re-edited, scenes reshot and deleted and entirely new scenes added. This made the plot even more confusing, partly because of the removal of an expository scene between Marlowe and the police. Both the coquettish Vickers and Dorothy Malone as a winsome book store salesgirl almost stole the film, to the disadvantage of Bacall, who, though sensational in some scenes, was borderline adequate in others. Some scenes of the two “encroaching” actresses were either trimmed or deleted, and new ones between Bogart and Bacall were filmed to exploit their chemistry.

Released first to the fighting men overseas, The Big Sleep was withheld from stateside release until Warner Brothers could issue its backlog of war films, now that the conflict was winding down. In the meantime, the movie was greatly revised—re-edited, scenes reshot and deleted and entirely new scenes added. This made the plot even more confusing, partly because of the removal of an expository scene between Marlowe and the police. Both the coquettish Vickers and Dorothy Malone as a winsome book store salesgirl almost stole the film, to the disadvantage of Bacall, who, though sensational in some scenes, was borderline adequate in others. Some scenes of the two “encroaching” actresses were either trimmed or deleted, and new ones between Bogart and Bacall were filmed to exploit their chemistry.

One such added scene is the now famous one at the racetrack, with its table talk seduction and the abundance of double-entendres:

“Speaking of horses,” Vivian says, “I like to play them myself. But I like to see them work out a little first. See if they’re front-runners or come from behind. Find out what their whole card is, what makes them run.”

“Find out mine?” Marlowe asks.

“I think so. . . . I’d say you don’t like to be rated. You like to get out in front, open up a little lead, take a little breather in the back stretch and then come home free.”

“You don’t like to be rated yourself.”

“I haven’t met any one yet that could do it. Any suggestions?”

“Well, I can’t tell ’til I’ve seen you over a distance of ground. You’ve got a touch of class, but I don’t know how far you can go.”

“A lot depends on who’s in the saddle.”

In the next pairing of Bogart and Bacall, Dark Passage (1947) borrows the theme of wife killer, used earlier in two weak Bogart pictures,Conflict and The Two Mrs. Carrolls. Bogart now plays escape prisoner Vincent Parry, convicted of murdering his wife but out to prove, in this case, his innocence. After he beats unconscious a motorist, Baker (Clifton Young), who had given him a lift and then became suspicious, Parry is picked up by Irene Jansen (Bacall) and taken to her San Francisco apartment. She has followed his case and believes him innocent. From a sympathetic cab driver, Parry is given the name of an underground plastic surgeon, and while his face heals, he stays with Jansen.

In the next pairing of Bogart and Bacall, Dark Passage (1947) borrows the theme of wife killer, used earlier in two weak Bogart pictures,Conflict and The Two Mrs. Carrolls. Bogart now plays escape prisoner Vincent Parry, convicted of murdering his wife but out to prove, in this case, his innocence. After he beats unconscious a motorist, Baker (Clifton Young), who had given him a lift and then became suspicious, Parry is picked up by Irene Jansen (Bacall) and taken to her San Francisco apartment. She has followed his case and believes him innocent. From a sympathetic cab driver, Parry is given the name of an underground plastic surgeon, and while his face heals, he stays with Jansen.

In a somewhat tedious and “arty” technique, before the surgery, the film’s viewpoint is seen through Parry’s eyes, and his “new” face isn’t seen for a good hour into the film. There are a number of implausible coincidences—for starters that Irene, a total stranger, just happens to have “followed his case” and that a friend of Irene’s, Madge (Agnes Moorehead), had been a girlfriend of Parry’s and had testified against him at his trial.

The deaths and convolutions typically mount. One of Parry’s friends, George (Rory Mallinson), is murdered. Parry is blackmailed by Baker, but the two have a fight, scenically beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, and Baker falls to his death. Confronting Madge, Parry accuses her of having killed both his wife and George. Accidentally (!), Madge also falls to her death—through a window in Parry’s presence, though not of his doing.

Knowing he cannot prove his innocence in all or any of these deaths, Parry telephones Irene that he’s going to South America. In the end ofDark Passage—it can’t be called a climax, maybe something of an anticlimax—Parry’s drinking at a bar in Peru is interrupted by the appearance of Irene. Apparently, all’s well that ends well. Simple solution to all problems: just walk out on the plot!

Throughout the film, Bogart maintains the hard, antihero image he established years earlier, especially in High Sierra, The Maltese Falcon andCasablanca. And Dark Passage is a hard and dark film.

Throughout the film, Bogart maintains the hard, antihero image he established years earlier, especially in High Sierra, The Maltese Falcon andCasablanca. And Dark Passage is a hard and dark film.

In Dark Passage, there are fewer magic moments between Bogart and Bacall than in the previous two films. As if screenwriter Delmer Davesis aware of the script’s shortcomings (the weakest of these four films)—no Hemmingway here as a source nor Faulkner to help—he plays an inside joke. After Irene has removed Parry’s bandages, and she and the audience see Bogart’s face for the first time, he says, “Baby!” She replies, “Here’s looking at you, kid!”—a line from Casablanca. And as if to reinforce the fact, Parry muses, “That’s my line.”

One critic, who shall remain nameless, wrote that none of Bogart and Bacall’s four films together are “more than adequate.” In fact, they areall above adequate, mainly because of competent direction, usually strong scripts and the chemistry between the two stars. The films are always joys to watch—Bacall gradually becoming a better actress and Bogart, though always remaining Bogart, holding the screen as well as any actor, then or now. Perhaps only in three films—The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The Caine Mutiny and The African Queen—does he really, and successfully, step outside of the Bogart mold, though he tried comedy (We’re No Angels), satire (Beat the Devil) and the light leading man (Sabrina).

And Key Largo (1948) is a fitting climax—and here there is a true climax—to the Bogart/Bacall quartet of Warner Brothers films. With direction by Bogart’s friend John Huston and script by Huston and Richard Brooks, this is the best of the four films, notwithstanding that it exploits the two stars’ chemistry the least: their characters are more like two lost souls consoling each other. Understandably, the claustrophobic, oppressive story line essentially limits much romantic development, and, too, Bogart’s character is embittered and unyielding. Key Largo is the only one of these four films to be nominated for an Oscar, Claire Trevor winning for Support Actress.

And Key Largo (1948) is a fitting climax—and here there is a true climax—to the Bogart/Bacall quartet of Warner Brothers films. With direction by Bogart’s friend John Huston and script by Huston and Richard Brooks, this is the best of the four films, notwithstanding that it exploits the two stars’ chemistry the least: their characters are more like two lost souls consoling each other. Understandably, the claustrophobic, oppressive story line essentially limits much romantic development, and, too, Bogart’s character is embittered and unyielding. Key Largo is the only one of these four films to be nominated for an Oscar, Claire Trevor winning for Support Actress.

Once again, as in To Have and Have Not, the plot of Key Largo has an island setting. World War II veteran Frank McCloud (Bogart) arrives in Key Largo, Florida, to visit the family of his friend George, killed in Italy—the father, James Temple (Lionel Barrymore), and his daughter and George’s widow Nora (Bacall). At the hotel, which James owns, Frank finds only six guests. He soon discovers they are mobster Johnny Rocco (Edward G. Robinson), his four “associates,” including another fat man (Thomas Gomez) and his alcoholic moll Gaye Dawn (Trevor). For a later run to Cuba, the gang has chartered a yacht, which is anchored off the coast to avoid damage from an approaching hurricane.

Frank is a disillusioned survivor of the horrors of war and an ultra antihero, to the point of showing cowardice in the face of the incriminationsand threats by the mobsters, particularly Rocco. He gives Frank a gun and challenges him to a duel, but Frank declines, saying “one more Rocco more or less isn’t worth dying for.” Later, the gun proves to be empty when a deputy sheriff (John Rodney) tries to use it and is killed by Rocco.

By the time the hurricane hits and begins battering the hotel, Rocco and his men have denied some local Seminole Indians the use of the building as a refuge and taken the Temples and Frank as hostage. Rocco deprives Gaye of her next needed drink until she sings for him and everyone gathered. Already drunk and disoriented, she protests but finally does sing—a cappella, and in a strained, off-key voice. Rocco tells her she’s “rotten” and denies her the drink. Frank defies Rocco—a cracking of his antihero shell—and gives Gaye a drink, which earns him three slaps from the gangster. Frank saunters away and sits down.

By the time the hurricane hits and begins battering the hotel, Rocco and his men have denied some local Seminole Indians the use of the building as a refuge and taken the Temples and Frank as hostage. Rocco deprives Gaye of her next needed drink until she sings for him and everyone gathered. Already drunk and disoriented, she protests but finally does sing—a cappella, and in a strained, off-key voice. Rocco tells her she’s “rotten” and denies her the drink. Frank defies Rocco—a cracking of his antihero shell—and gives Gaye a drink, which earns him three slaps from the gangster. Frank saunters away and sits down.

Later, when the yacht has left for safer waters, the mobsters commandeer the boat belonging to the hotel for their break to Cuba, forcing Frank, coincidentally a qualified seaman, to take them. Rocco says Gaye isn’t going. Her embrace of the gangster and plea to be taken is only a ruse to steal from his pocket his gun, which she slips to Frank.

In the Straits of Florida, Frank finally tosses off his antihero shroud and disposes of the mobsters, either pitching them overboard or shooting them before killing Rocco in a grand-style shootout. (With Huston in need of an ending, he borrowed Hawks’ unused idea from To Have and Have Not.) Though wounded, Frank calls the hotel and tells Nora and her father that he’s on his way back.

A fifth Bogart/Bacall teaming was planned, based on John P. Marquand’s novel Melville Goodwin, U.S.A., about a gung ho army general and a journalist out to get him. Released in 1957, the year of Bogart’s death, its title was changed to Top Secret Affair and starred Kirk Douglas and Susan Hayward.

In her seventy-year career, Bacall starred in many films, including How to Marry a Millionaire, Blood Alley with John Wayne and again in his last film, The Shootist, Designing Women with Gregory Peck, Harper opposite Paul Newman and Murder on the Orient Express as the ringer leader of the murder scheme. She received an Oscar nomination for Supporting Actress in The Mirror Has Two Faces, playing the mother of Barbara Streisand, and an Honorary Award in 2010 for “recognition of her central place in the Golden Age of motion pictures.”

In her seventy-year career, Bacall starred in many films, including How to Marry a Millionaire, Blood Alley with John Wayne and again in his last film, The Shootist, Designing Women with Gregory Peck, Harper opposite Paul Newman and Murder on the Orient Express as the ringer leader of the murder scheme. She received an Oscar nomination for Supporting Actress in The Mirror Has Two Faces, playing the mother of Barbara Streisand, and an Honorary Award in 2010 for “recognition of her central place in the Golden Age of motion pictures.”

Among her numerous television appearances was in a two-part episode of James Garner’s The Rockford Files and as narrator of the PBS “The Gift of Music,” about her friend Leonard Bernstein. She appeared in a number of Broadway plays, including Cactus Flower and Applause.

In the third-to-last paragraph of Lauren Bacall’s original By Myself, she sums up the tie between herself and this man Bogart: “And Bogie, with his great ability to love, never suppressing me, helping me to keep my values straight in a town where there were few, forcing my standards higher—again the stress on personal character, demonstrating the importance of the quality of life, the proper attitude toward work. To be good was more important than to be rich. To be kind was more important than owning a house or a car. To respect one’s work and to do it well, to risk something in life, was more important than being a star. To never sell your soul—to have self-esteem—to be true—was most important of all.”

The paragraph says as much about Bogie as it does about that girl with “The Look.”