“I don’t know [why a man chases women]. Maybe because he fears death.”— Johnny to Rose

“I don’t know [why a man chases women]. Maybe because he fears death.”— Johnny to Rose

Nothing deep, Moonstruck is, rather, a warm diversion, a movie to watch on a cold night, or, for that matter, on a warm day—but not if someone is depressed, ’cause it’ll certainly lift any dark clouds and bring a smile, probably more than a several dozen laughs.

While cleverly avoiding slapstick, it centers on the love of life, Italian style, here in probably a bigger effusion than even the way real Italians celebrate life. Here are all the slants on their Latin traits—a bit about religion, more about the effects of the moon on the libido and still more about the theme of Death as raised by a family matriarch, who wanders through the plot like a Demosthenes, lantern held high, only here looking, not for an honest man, perhaps because she knows they don’t exist, but for the answer to a vital, personal question.

And, of course, there’s the almost constant presence of food, food and more food—at the breakfast or dining room table of the central family here, the Castorini’s; food in restaurants, food as a prelude to lovemaking. Food, sometimes, as an excuse for family dialogues and one-liners, even about good food wasted, such as that remark by that matriarch directed at her father-in-law: “Old man, you give those dogs another piece of my food and I’m gonna kick you ’til you’re dead!”

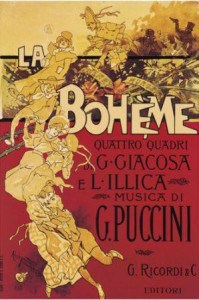

Love, like an antidote to death, is the cornerstone in Moonstruck—for one character seeking a quick escape from a long marriage, for another discovering romance unexpectedly, for still another finding someone who “could have been” under other circumstances. Everybody’s busy with love. Appropriately, then, behind the main title Dean Martin sings “That’s Amore,” and music of a quite different type practically saturates the film. For some viewers it may be absorbed only subliminally, and that is the sentimentality of opera, specifically Puccini, more specifically his La Bohème, which continues two of the film’s major themes, love and death.

The late Premiere Magazine’s ranking Moonstruck ninth among the most overrated movies of all time glaringly conflicts with the American Film Institute’s placing it eighth among the greatest of romantic comedies—the same conflict this writer has with that magazine, which ceased publication in 2007. “The movie makes you laugh,” Roger Ebert wrote, “ . . . , but it also makes you feel more open to your better impulses, and that is harder still.”

One can wonder how such an Italian-feeling movie could succeed so well—and it does—when so few participants are Italian. Certainly not Canadian director Norman Jewison, responsible for the original Thomas Crown Affair, Agnes of God and, above all, In the Heat of the Night. Nor screenwriter John Patrick Shanley, who, quite different from the exuberant, adventurous Castorinis and their friends, came from an Irish family of sexual repression and unimaginative meals. He also wrote screenplays for Congo and, more recently, Doubt.

One can wonder how such an Italian-feeling movie could succeed so well—and it does—when so few participants are Italian. Certainly not Canadian director Norman Jewison, responsible for the original Thomas Crown Affair, Agnes of God and, above all, In the Heat of the Night. Nor screenwriter John Patrick Shanley, who, quite different from the exuberant, adventurous Castorinis and their friends, came from an Irish family of sexual repression and unimaginative meals. He also wrote screenplays for Congo and, more recently, Doubt.

Nor remotely Italian is Cher, whose credits include Silkwoodand The Witches of Eastwick, she of mixed heritage, from way to the north and east of Italy. Nor Olympia Dukakis, of Greek immigrants, who wasn’t on the movie map, in fact, until Moonstruck. Nor John Mahoney—Kelsey Grammer’s father in TV’s Frasier—originally English, having lost his accent during service in the U.S. Army. Nor the minor but important actor Feodor Chaliapin, listed without his proper “Jr.,” as he was born in Moscow, the son of the famous Russian operatic bass.

The Italian influences do occur with Nicolas Cage, who, half-Italian, was the wild man on the Moonstruck set, the opaque method actor, almost dropped by the studio except for Cher’s intervention. And then the remaining major cast members, Vincent Gardenia, Danny Aiello and Julie Bovasso, have definite Italian connections. Gardenia even auditioned part of his role for the movie in Italian.

Shanley had originally scripted the film to open with La Bohème, with a conductor rapping on his music stand before launching into the opera,but the preview audience was totally turned off—opera and all that Italian!—thinking this was “some kind of artsy, fartsy film” (his words). Puccini’s music still plays a large part in the movie, but the main title shows onlythe sets for La Bohème being trucked to the Met, with Martin’s “That’s Amore” on the soundtrack. In keeping with the general buoyancy of the movie, this choice is much more appropriate.

Shanley had originally scripted the film to open with La Bohème, with a conductor rapping on his music stand before launching into the opera,but the preview audience was totally turned off—opera and all that Italian!—thinking this was “some kind of artsy, fartsy film” (his words). Puccini’s music still plays a large part in the movie, but the main title shows onlythe sets for La Bohème being trucked to the Met, with Martin’s “That’s Amore” on the soundtrack. In keeping with the general buoyancy of the movie, this choice is much more appropriate.

Moonstruckis about several New York Italian-American families, connected by marriage, friendship or employment, mainly the Castorinis, three generations of which live in the same big Brooklyn house where much of the action takes place, usually while someone, sometimes everyone, is eating or drinking. The kitchen is where all important announcements and decisions are made.

The sub-theme of death is established immediately. Jewison’s main title credit is given against a corpse in a coffin in a funeral home where Loretta Castorini (Cher) is the bookkeeper. Her father, rich plumber Cosmo (Gardenia), is introduced telling his daughter that he can’t sleep—“too much like death.” He is cheating on wife Rose (Dukakis, in a great performance), who suspects that men chase women because they fear death.

Loretta, whose first husband of a few years was run over by a bus, has agreed, surrounded by food and dessert in a restaurant, to marry a “big baby,” Johnny Cammareri (Aiello). Clearly the boss, she tells him what he should eat and that he needs to get on his knees if he’s going to propose. When Loretta and her father wake Rose to tell her the news, she says, “Who’s dead?” Rose asks her if she loves Johnny. When she replies no, though adding he’s a nice, sweet man, Rose replies, “Good. When you love ’em, they drive you crazy because they know they can.” She looks at Cosmo when she says it, and will ask Loretta the same question again in the film’s climax.

Loretta, whose first husband of a few years was run over by a bus, has agreed, surrounded by food and dessert in a restaurant, to marry a “big baby,” Johnny Cammareri (Aiello). Clearly the boss, she tells him what he should eat and that he needs to get on his knees if he’s going to propose. When Loretta and her father wake Rose to tell her the news, she says, “Who’s dead?” Rose asks her if she loves Johnny. When she replies no, though adding he’s a nice, sweet man, Rose replies, “Good. When you love ’em, they drive you crazy because they know they can.” She looks at Cosmo when she says it, and will ask Loretta the same question again in the film’s climax.

Johnny, however, can’t marry Loretta until his mother, dying in Sicily, has passed. They decide on a month from now for the wedding, and he flies off for the deathwatch. Johnny has asked Loretta to contact his estranged brother Ronny (Cage) and invite him to the wedding. She tracks him down in a bakery. He emerges from the shadows of the dark basement like some kind of Vulcan brute, with spiked hair, a wild look and in a tank top revealing shiny, sweaty muscles. “They say bread is life,” he shouts to her. “And I bake bread, bread, bread. And I sweat and shovel this stinkin’ dough in and out of this hot hole in the wall, and I should be so happy! Huh, sweetie?”

The bad blood between the two brothers is Ronny’s animosity: while distracted in Johnny’s presence, Ronny accidentally cut off his left hand in the bread slicer, and, thus maimed, his girl dropped him. He threatens cutting his throat in front of Loretta. “Bring me the big knife!” he screams to an assistant (Nada Despotovich).

The bad blood between the two brothers is Ronny’s animosity: while distracted in Johnny’s presence, Ronny accidentally cut off his left hand in the bread slicer, and, thus maimed, his girl dropped him. He threatens cutting his throat in front of Loretta. “Bring me the big knife!” he screams to an assistant (Nada Despotovich).

This scene, and Cage’s performance in general, can make or break Moonstruck, depending upon one’s viewpoint. His acting is either some kind of weird tour de force, a fascinating novelty, that, against all logic, is effective, or, as I see it, an absurd eccentricity that doesn’t quite come off; it disturbs the tone of the film.

Intercut with this scene, Cosmo is at a restaurant with his mistress Mona (Anita Gillette), giving her a cheap bracelet and strutting his salesmanship. In the previous scene, he had delivered what could be called his “Copper Pipe Speech.” As a plumber, he is selling a young couple on the superiority of copper pipe: “There are three kinds of pipe. There’s what you have, which is garbage—and you can see where that’s gotten you. There’s bronze, which is pretty good, unless something goes wrong—and something always goes wrong. Then there’s copper, which is the only pipe I use. It costs money. It costs money because it saves money.” Easily impressed, Mona gushes, “You have such a head for knowing. You know everything.”

Within an hour after meeting, following a steak dinner Loretta prepares for him, she and Ronny make love in a room over the bakery. “Hollow me out,” she cries, “so there’s nothing left but the skin over my bones. Suck me dry!” He concurs: “All right. All right. There will be nothing left!” They are accompanied by “O soave fanciulla,” the climax of Act I of La Bohème.

Within an hour after meeting, following a steak dinner Loretta prepares for him, she and Ronny make love in a room over the bakery. “Hollow me out,” she cries, “so there’s nothing left but the skin over my bones. Suck me dry!” He concurs: “All right. All right. There will be nothing left!” They are accompanied by “O soave fanciulla,” the climax of Act I of La Bohème.

Earlier, just after his first kiss and her,“Wait a minute! Wait a minute!”—said in vain, obviously—there are a few notes from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, the famous “Tristanchord,” perhaps an in-joke by composer Dick Hyman. (Wagner’s great rival was not Puccini, who came almost two generations later, but Giuseppe Verdi.) Later, after cutting to other scenes, Loretta and Ronnie arise the next morning. He confesses he loves her. She slaps him, not once but twice, and declares, “Snap out of it!,” one of the most famous lines from the film, though not the best.

Loretta tells Ronny she wants him out of her life, that the affair never happened. Okay, he says, he will give her up if she’ll go to the opera with him, because only two things matter in his life—her and “the opera.” She agrees, but showing her cultural deficiency, turns back to ask, “Where’s the Met?” At a hair salon and a boutique she is transformed from sloppy Loretta—Cher is never that “sloppy”—to Cinderella on her way to the ball. Ronny is her Prince, out of his baker/blacksmith clothes and into tie and tails, hair slicked down.

Loretta tells Ronny she wants him out of her life, that the affair never happened. Okay, he says, he will give her up if she’ll go to the opera with him, because only two things matter in his life—her and “the opera.” She agrees, but showing her cultural deficiency, turns back to ask, “Where’s the Met?” At a hair salon and a boutique she is transformed from sloppy Loretta—Cher is never that “sloppy”—to Cinderella on her way to the ball. Ronny is her Prince, out of his baker/blacksmith clothes and into tie and tails, hair slicked down.

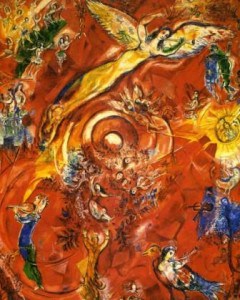

The two lovers hold hands and she tears up, romantically moved by the opera—Mimì’s Act II farewell to Rudolfo, “Donde lieta usci al tuo grido d’amore,” in a snowfall, with a suspended moon. Descending the staircase at Lincoln Center afterward, Loretta wonders, “You know, I didn’t really think she was gonna die. I knew she was sick——” In the foyer, Loretta confronts her father with his mistress. On the walls are the great paintings of Marc Chagall, which Loretta calls “kinda gaudy,” and a portrait of Richard Strauss.

Walking back after the opera, Loretta and Ronny reach his place. He says he loves her. “You gonna marry my brother? . . . You waited for the right man the first time, why didn’t you wait for the right man again?” “He didn’t come!” she says. “I’m here!’ he replies. “You’re late!” she says. He takes her to his bed again—more Puccini—and afterward they are entranced by the moon.

Walking back after the opera, Loretta and Ronny reach his place. He says he loves her. “You gonna marry my brother? . . . You waited for the right man the first time, why didn’t you wait for the right man again?” “He didn’t come!” she says. “I’m here!’ he replies. “You’re late!” she says. He takes her to his bed again—more Puccini—and afterward they are entranced by the moon.

Another couple, Rita and Raymond Cappomaggi, coming under the category of “sweet and endearing,” are also romantically stimulated by the moon. Rita is Rose’s sister. They are played by Julie Bovasso and Louis Guss. Together, they run a delicatessen, where Loretta is the bookkeeper, who takes the week’s profits to the bank.

Quite often in Moonstruck, scenes aren’t cut, adjacent to one another, but are bridged by someone walking, a kind of promenade, usually to Italian accordion music, Will Hudson and Irving Mills’ “Moonglow,” bits from La Bohème, including the purely orchestral “Musetta’s Entry” and her famous waltz, or something of Hyman’s own devising.

Cosmo’s father (Chaliapin) is forever out walking his five dogs. On the first occasion, he takes the animals across the street, passes through a gate marked“No Dogs Allowed” and lets them go in a little park. One of his outing is an Italian tribute to the moon, with the Brooklyn Bridge in the distance; after imitating a howl, he inspires his dogs to howl, prompting his endless laughter. One night, while escorting his dogs, he meets Rose, out walking with a man (Mahoney, this six years before In the Line of Fire and Frasier).

Cosmo’s father (Chaliapin) is forever out walking his five dogs. On the first occasion, he takes the animals across the street, passes through a gate marked“No Dogs Allowed” and lets them go in a little park. One of his outing is an Italian tribute to the moon, with the Brooklyn Bridge in the distance; after imitating a howl, he inspires his dogs to howl, prompting his endless laughter. One night, while escorting his dogs, he meets Rose, out walking with a man (Mahoney, this six years before In the Line of Fire and Frasier).

As Perry, a college professor, Mahoney has two scenes in a restaurant where young girls throw drinks at him and walk out, the first during Johnny’s proposal to Loretta. On the second soaking, which is intercut with Loretta and Ronny at the Met, Rose is at the next table, eating alone. She invites Perry over and asks him, “Why do men chase women?” He gives a feeble answer, beginning, “It’s nerves,” whereupon she presents her theory. Although she is too old for him, they have much in common and hit it off—up to a point. As he’s walking her home, he suggests he go up with her to her three-story “mansion,” he calls it. She says no, that she’s married and, besides,“I know who I am.”

As Perry, a college professor, Mahoney has two scenes in a restaurant where young girls throw drinks at him and walk out, the first during Johnny’s proposal to Loretta. On the second soaking, which is intercut with Loretta and Ronny at the Met, Rose is at the next table, eating alone. She invites Perry over and asks him, “Why do men chase women?” He gives a feeble answer, beginning, “It’s nerves,” whereupon she presents her theory. Although she is too old for him, they have much in common and hit it off—up to a point. As he’s walking her home, he suggests he go up with her to her three-story “mansion,” he calls it. She says no, that she’s married and, besides,“I know who I am.”

Johnny returns from Sicily: his mother has recovered. When he arrives at the Castorini’s, Loretta is not at home. Rose asks him her question. He first suggests men chase women because God took a rib from Adam to make Eve and men have always wanted that rib back, and, too, a man needs a woman to be complete, but also, he wonders, maybe it’s because . . . men fear death. Rose thanks him, saying he’s answered her question, as if she hadn’t answered it herself long ago! Johnny says he’ll be back, that he must talk to Loretta. Then Cosmo comes home. Rose tells him, “I just want you to know, no matter what you do, you’re gonna die, just like everybody else.” He replies,“Thank you, Rose,” and goes upstairs.

The climax of the film is the long, final scene at the kitchen table, where, one by one, most of the cast arrives. It’s like an octet in an opera finale, which seems only apropos. When Loretta enters with love bites on her neck, Rose tells her to put on some makeup. Then Ronny arrives, also with love bites, and when Loretta shouts that he can’t stay, he replies to an earlier offer,“Yes, Mrs. Castorini, I would LOVE some oatmeal.” Cosmo comes down from upstairs and the grandfather arrives, sans dogs. Rose tells her husband, “I want you to stop seeing her. . . . And go to confession.”

The climax of the film is the long, final scene at the kitchen table, where, one by one, most of the cast arrives. It’s like an octet in an opera finale, which seems only apropos. When Loretta enters with love bites on her neck, Rose tells her to put on some makeup. Then Ronny arrives, also with love bites, and when Loretta shouts that he can’t stay, he replies to an earlier offer,“Yes, Mrs. Castorini, I would LOVE some oatmeal.” Cosmo comes down from upstairs and the grandfather arrives, sans dogs. Rose tells her husband, “I want you to stop seeing her. . . . And go to confession.”

Then Rita and Raymond arrive to check on why Loretta didn’t bank the money from the delicatessen and are relieved that she has it, had simply forgotten. Now they all wait for Johnny to return. After a long pause—seven around the table now—the grandfather says, “Someone tell a joke.” When Johnny does arrive, he says he can’t marry Loretta, that, if he does, his mother will die. She throws him the “pinky” ring. Ronny proposes to Loretta, asking his brother to loan him the ring. Loretta accepts. Everybody seems happy. Cosmo asks, “What’s the matter, pop?” “I’m confused,” the old man replies, crying.

And the question that Rose had asked Loretta about Johnny is repeated at the kitchen table, now regarding Ronny:“Do you love him?” Loretta replies, “Ah, ma, I love him awful.” She replies, “Oh, God, that’s too bad.”

And the question that Rose had asked Loretta about Johnny is repeated at the kitchen table, now regarding Ronny:“Do you love him?” Loretta replies, “Ah, ma, I love him awful.” She replies, “Oh, God, that’s too bad.”

Beautiful voices from La Bohème return as the camera pans the living room with its crowded photographs of generations of Castorinis—life is, after all, about family—and “That’s Amore” floats in again as the end credits roll.

If Cage’s performance is certainly the strangest and, to some viewers, the most problematic in Moonstruck, then Dukakis’ is the one that holds everything together, as Rose holds together the Castorini family, without—and no small feat—coming apart herself from the strain. Good enough a performance to win a Supporting Actress Academy Award. It’s amazing how expressive, how convincing are her observations on the human condition, especially regarding that question of hers, when conveyed in that often droll, deadpan delivery.

Cher, in surely one of her best performances, earning a Best Actress Oscar, has pretty much mastered the Brooklyn accent, her largest hurdle. Like Liza Minnelli’s persona, that is, one difficult to act above or overcome, Cher seems less like Cher, and more like Loretta Castorini. She is convincing as an Italian-American who fears her first marriage was cursed—remember the bus?!—for its civil ceremony and wants to save the second, when it would have been to Johnny Cammareri, by a proper wedding in a Catholic church.

Cher, in surely one of her best performances, earning a Best Actress Oscar, has pretty much mastered the Brooklyn accent, her largest hurdle. Like Liza Minnelli’s persona, that is, one difficult to act above or overcome, Cher seems less like Cher, and more like Loretta Castorini. She is convincing as an Italian-American who fears her first marriage was cursed—remember the bus?!—for its civil ceremony and wants to save the second, when it would have been to Johnny Cammareri, by a proper wedding in a Catholic church.

Vincent Gardenia, another excellent player in an over-all excellent ensemble, was awarded a Best Supporting Actor nomination, but that’s as far as it went, losing, along with his three other nominees, to Sean Connery for The Untouchables. The other performers, Italian or not, are equal “members of the family”—Danny Aiello, Julie Bovasso and Feodor Chaliapin. Not to be forgotten—the only one unconnected with the others, in nationality or temperament—is John Mahoney, who is memorable himself.

Norman Jewison’s nomination for Best Director, like Moonstruck’s for Best Picture, lost to The Last Emperor, a win which now seems, after the test of time, a misguided award, rendered to so many big pictures with exotic settings and that aura of for-the-moment novelty. Shanley easily won Best Original Screenplay, with stiffest competition from Woody Allen for Radio Days and James Brooks for Broadcast News.

If nothing else, the general public’s exposure to Moonstruck has introduced many an unsuspecting movie-goer and opera-hater to the gorgeous music of Giacomo Puccini and his most beautiful and melodic opera. On the filmsoundtrack, Mimì and Rudolfo are sung by Renata Tebaldi and Carlo Bergonzi from a 1959 recording. The opera scene Loretta and Ronny watch is not from a Met performance, but from the Canadian Opera.

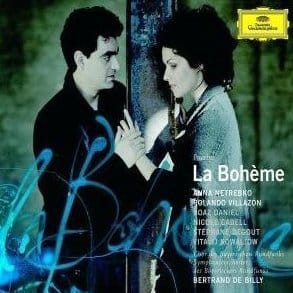

For those viewers who would like to investigate La Bohème further, a good CD choice is the Decca 1972 recording with Luciano Pavarotti as Rodolfo—“perhaps the best thing he ever did,” Gramophone magazine has proclaimed. For a more recent, fully digital version, there is the 2007 Deutsche Grammophon recording with Anna Netrebko as Mimì and Rolando Villazón as Rodolfo.

For those viewers who would like to investigate La Bohème further, a good CD choice is the Decca 1972 recording with Luciano Pavarotti as Rodolfo—“perhaps the best thing he ever did,” Gramophone magazine has proclaimed. For a more recent, fully digital version, there is the 2007 Deutsche Grammophon recording with Anna Netrebko as Mimì and Rolando Villazón as Rodolfo.

Like Moonstruck,La Bohème is about love and . . . what was that other? . . . Death.