Two great lovers of the screen in the grandest of romantic comedies!

So—when or where did it happen? Certainly not in Brooklyn as it did for Frank Sinatra and Kathryn Grayson in 1947. Nor in Athens for Jayne Mansfield fifteen years later—wrong continent. As for a season of the year, nor did it happen Every Spring, as it surely did for Ray Milland and Jean Peters in 1949, nor on a day of the week, as it occurred for Loretta Young and John Forsythe Every Thursday in 1953. Nor did it happen One Christmas, at the World’s Fair, Tomorrow, or on Fifth Avenue—all words in movie titles that begin It Happened——”

In fact, when it did happened was . . . one night, not the first or even the second night. That partly settled, what was the “it” that happened? Probably easy to guess, and though “it” could have happened earlier, “it” happened later, at the end of this particular movie.

Embarrassing as it is, only “the other day,” as the trite phrase goes, did I see It Happened One Night for the first time in my life, after all these years. Think of all the viewings I could have enjoyed, all the appreciation, perhaps even greater than now, I could have acquired. Similar to Roger Ebert’s remark that, of all movies, he couldn’t imagine never seeing Casablanca again, I can’t imagine going so long without seeing It Happened One Night.

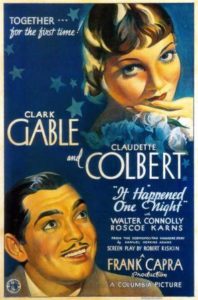

Against all the artistic and social trends it inspired, the parodies and remakes it spawned, the film began life with much against it. Neither of its two stars was director Frank Capra’s first choice. As the eventual leading man, Clark Gable always felt that his loan out by that roaring giant M-G-M to the then poverty row studio Columbia was punishment for a contractual indiscretion, and he walked on the set the first day saying, “Let’s get this thing over with.” (After the fact, however, he corrected that first impression: “But I hadn’t read twenty pages of the script before I knew it would turn out all right.”)

Against all the artistic and social trends it inspired, the parodies and remakes it spawned, the film began life with much against it. Neither of its two stars was director Frank Capra’s first choice. As the eventual leading man, Clark Gable always felt that his loan out by that roaring giant M-G-M to the then poverty row studio Columbia was punishment for a contractual indiscretion, and he walked on the set the first day saying, “Let’s get this thing over with.” (After the fact, however, he corrected that first impression: “But I hadn’t read twenty pages of the script before I knew it would turn out all right.”)

After Myrna Loy, Constance Bennett, Carole Lombard, Miriam Hopkins and others had turned down the female lead, Claudette Colbert was persuaded to accept it—only after a double in salary and the assurance of a quick, four-week shooting schedule. At the end of filming, she remarked, “I just finished making the worst picture I’ve ever made.”

Nor did any one seem to think much of Robert Riskin’s screenplay, based on Night Bus, a short story by Samuel Hopkins Adams. Robert Montgomery, one of the actors who had turned down Gable’s part, observed that it was the worst thing he had ever seen. Riskin was Capra’s partner in a number of other brilliant collaborations—in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take It With You and Meet John Doe. Riskin received five Oscar nominations, all for Capra films, and was denied a win in all of them except for One Night. The script must have been a little better than most people thought, and there’s the evidence on screen to justify its vibrant quality.

Nor did any one seem to think much of Robert Riskin’s screenplay, based on Night Bus, a short story by Samuel Hopkins Adams. Robert Montgomery, one of the actors who had turned down Gable’s part, observed that it was the worst thing he had ever seen. Riskin was Capra’s partner in a number of other brilliant collaborations—in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take It With You and Meet John Doe. Riskin received five Oscar nominations, all for Capra films, and was denied a win in all of them except for One Night. The script must have been a little better than most people thought, and there’s the evidence on screen to justify its vibrant quality.

More than a romantic comedy and a road picture extraordinaire, the movie was the first of what would be called screwball comedies. With a small budget—the studio being Columbia—and filmed quickly, mainly because of Colbert’s demands, the resulting lively pace was a key ingredient in the film’s boundless fun, success and popularity, which lifted Columbia out of the cellar in the hierarchy of Hollywood studios. As well, the film provided the perfect escapism for the down-trodden of the Depression, and remains today as fresh as ever.

The two stars, despite their dislike of the enterprise, seemed to fall naturally into the spirit of the story, creating a bantering chemistry rarely seen and both giving one of the best performances of their careers. Conceivably, it was their shared view that they were making a stinker, and could therefore care less, that their approach was so relaxed and seemingly spontaneous.

The two stars, despite their dislike of the enterprise, seemed to fall naturally into the spirit of the story, creating a bantering chemistry rarely seen and both giving one of the best performances of their careers. Conceivably, it was their shared view that they were making a stinker, and could therefore care less, that their approach was so relaxed and seemingly spontaneous.

The night of the Oscar ceremony, February 27, 1935, One Night was the first film in history to win the top five trophies—picture, actor, actress, director and screenwriter. This would not happen again until 1975 with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and again in 1991 with Silence of the Lambs.

For her part, Claudette Colbert was in two other nominated best films of 1934, Cleopatra and Imitation of Life. In such a hurry, and so disdainful of One Night and her chances at a Best Actress win, she skipped the ceremonies, and was boarding a train when Academy officials informed her she had won the Oscar. Dressed in a traveling suit, she arrived at the Biltmore Bowl, accepted her award, posed for photographs and was back on the train, which had been held for her return.

I t Happened One Night was brilliantly restored in 2013 by Sony Colorworks. Overcoming the flaws in the much abused master negative, which had been used for making distribution prints, and restoring some poor quality scenes that had replaced the original negative was a challenge for the technicians in their 4K restoration. This was brilliantly accomplished, while at the same time removing dust, scratches and other blemishes. Rita Belda, in charge of the Sony restoration, remarked that cinematographer “ . . . Joseph Walker . . . used filters to create a soft, glowing look . . . The result is a rich look with a lot of range in the mid-tones. The amount of detail in the negative was startling.”

t Happened One Night was brilliantly restored in 2013 by Sony Colorworks. Overcoming the flaws in the much abused master negative, which had been used for making distribution prints, and restoring some poor quality scenes that had replaced the original negative was a challenge for the technicians in their 4K restoration. This was brilliantly accomplished, while at the same time removing dust, scratches and other blemishes. Rita Belda, in charge of the Sony restoration, remarked that cinematographer “ . . . Joseph Walker . . . used filters to create a soft, glowing look . . . The result is a rich look with a lot of range in the mid-tones. The amount of detail in the negative was startling.”

Ellie Andrews (Colbert), a spoiled heiress who had eloped and married the fortune-hunting “King” Westley (Jameson Thomas, later the nose-twitching Semple in another Capra masterpiece, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town), is kidnapped by her father, millionaire Alexander (Walter Connolly), who dislikes Westley. Ellie escapes Alexander’s yacht anchored in Miami and heads for New York to rejoin Westley.

On a bus, she meets Peter Warne (Gable), a newspaper reporter who has recently lost his job. They reluctantly share the back seat because the bus is full. The bus driver is Ward Bond, who has an “oh, yeah?” shout down with Gable. (Here are more instances of the long, unbroken takes by Capra’s regular cinematographer Joseph Walker, who photographed all the Capra films mentioned earlier except Meet John Doe.)

On a bus, she meets Peter Warne (Gable), a newspaper reporter who has recently lost his job. They reluctantly share the back seat because the bus is full. The bus driver is Ward Bond, who has an “oh, yeah?” shout down with Gable. (Here are more instances of the long, unbroken takes by Capra’s regular cinematographer Joseph Walker, who photographed all the Capra films mentioned earlier except Meet John Doe.)

At another stop, now in Jacksonville, Ellie tells the driver to wait while she goes to freshen up, and she returns to find the bus gone. Peter has waited for her, handing her the bus ticket she left on the seat and showing her a newspaper headlining her identity and her father’s offer of a reward for her return. In the first of several monologues, Warne renders his “spoiled brat” speech, ending, “I’m not interested in your money or your problem. You, ‘King’ Westley, your father—you’re all a lot of hooey to me.”

The two are together on the next bus north, though in seats across the aisle. In the empty seat beside Ellie, a fast-talker, Oscar Shapeley (Roscoe Karns), tries to pick her up. “Yes, sir, when a cold mama gets hot, boy, how she sizzles,” he says. “Now you’re just my type. Believe me, sister, I could go for you in a big way.” Warne intrudes, saying he would like to sit beside his “wife.” She attempts a “thank you,” but he shrugs it off. “Forget it. I didn’t do it for you. His voice got on my nerves.”

The two are together on the next bus north, though in seats across the aisle. In the empty seat beside Ellie, a fast-talker, Oscar Shapeley (Roscoe Karns), tries to pick her up. “Yes, sir, when a cold mama gets hot, boy, how she sizzles,” he says. “Now you’re just my type. Believe me, sister, I could go for you in a big way.” Warne intrudes, saying he would like to sit beside his “wife.” She attempts a “thank you,” but he shrugs it off. “Forget it. I didn’t do it for you. His voice got on my nerves.”

(Although the Motion Picture Production code was adopted in 1930, it was not strictly enforced until July 1, 1934, some four months after One Night was released. Shapeley’s raunchy lines, at least raunchy by the standards of the time, were allowed, as well as other “compromising” situations and inferences, such as Colbert later leaning on Gable’s bed.)

When the bus runs off the road in a rainstorm, the couple are forced to spend the night at Duke’s Auto Camp—$2 a night, with showers in a separate building. This, maybe the best part of the film, features many delights and important plot turns. First, Warne proposes to Ellie that if she will give him an exclusive story, a day-by-day account of her journey to New York—“all about your mad flight to happiness”—he’ll help reunite her with Westley.

When the bus runs off the road in a rainstorm, the couple are forced to spend the night at Duke’s Auto Camp—$2 a night, with showers in a separate building. This, maybe the best part of the film, features many delights and important plot turns. First, Warne proposes to Ellie that if she will give him an exclusive story, a day-by-day account of her journey to New York—“all about your mad flight to happiness”—he’ll help reunite her with Westley.

Second, there is the famous “Walls of Jericho” scene, where Warne hangs a blanket between the two twin beds—a rope is conveniently on hand—and demonstrates how a man undresses for bed. “No two men do it alike,” he begins. “If you notice, the coat came first, then the tie, then the shirt . . . uh, pants should be next. There’s where I’m different. I go for the shoes next. . . . After that it’s, uh, every man for himself.” (Because Gable wore no undershirt, sales of the apparel dropped drastically and the industry threatened to sue Columbia.)

Next comes the extended breakfast scene where Peter shows Ellie the proper way to dunk donuts—“Say,” he asks, “where did you learn to dunk, in finishing school?”—and she reveals that, though she’s supposed to be a spoiled socialite, she’s lived a very restricted life, always accompanied by bodyguards. This is the first time, she admits, that she’s ever been alone with a man.

Next comes the extended breakfast scene where Peter shows Ellie the proper way to dunk donuts—“Say,” he asks, “where did you learn to dunk, in finishing school?”—and she reveals that, though she’s supposed to be a spoiled socialite, she’s lived a very restricted life, always accompanied by bodyguards. This is the first time, she admits, that she’s ever been alone with a man.

Finally, in this scene there’s their great pretense as a bickering couple when her father’s two detectives arrive. As unwelcome voices are heard outside and there’s a knock on the door, Peter musses her hair and unbuttons the top of her blouse—she doesn’t seem to object. They shout and scream at one another, Ellie adopting a Southern accent. And laugh hilariously after the detectives have apologized for the intrusion and departed.

Shapeley, who also has read a paper and discovered Ellie’s identity, threatens Warne with exposure unless he agrees to a fifty-fifty split of the reward money. Warne instantly assumes the guise of a gangster, with an implied pistol in his pocket and the boast of two machine guns in his suitcase. He welcomes Shapeley to the gang; the reward is chicken feed—they’re going to get a million for this dame. Shapeley, realizing he’s in over his head, backs down, now frightened by threats to his family if he squeals, and dashes off into the woods.

Shapeley, who also has read a paper and discovered Ellie’s identity, threatens Warne with exposure unless he agrees to a fifty-fifty split of the reward money. Warne instantly assumes the guise of a gangster, with an implied pistol in his pocket and the boast of two machine guns in his suitcase. He welcomes Shapeley to the gang; the reward is chicken feed—they’re going to get a million for this dame. Shapeley, realizing he’s in over his head, backs down, now frightened by threats to his family if he squeals, and dashes off into the woods.

Warne thinks it’s best to abandon the bus, so he and Ellie also take to the woods. Here, too, is more banter between them—a piggyback ride for her across a stream, his assurance that she can’t be both hungry and scared at the same time and his making separate beds out of hay. While he is out foraging for food, she suddenly realizes he is gone, hugging him when he returns with some raw carrots, which she refuses to eat. When he covers her with his coat for the night, he almost kisses her—but not quite.

Next morning, they hit the road. “You’ve given me a very good example of the hiking,” she says as they trudge along. “Where does the hitching come in?” After Peter demonstrates his foolproof techniques for thumbing a ride and all prove unsuccessful, as countless cars zoom by, Ellie walks to the road. “I’ll stop a car and I won’t use my thumb,” she says. As the next car approaches, she lifts her skirt, revealing a luscious left leg. The foot of a driver, Danker (Alan Hale), slams on the brake, a hand yanks back the emergency and a spoke wheel (this was a Model-T) skids stiffly across the pavement. Another famous image from the film.

Next morning, they hit the road. “You’ve given me a very good example of the hiking,” she says as they trudge along. “Where does the hitching come in?” After Peter demonstrates his foolproof techniques for thumbing a ride and all prove unsuccessful, as countless cars zoom by, Ellie walks to the road. “I’ll stop a car and I won’t use my thumb,” she says. As the next car approaches, she lifts her skirt, revealing a luscious left leg. The foot of a driver, Danker (Alan Hale), slams on the brake, a hand yanks back the emergency and a spoke wheel (this was a Model-T) skids stiffly across the pavement. Another famous image from the film.

After Danker leaves the couple at a rest stop and Warne runs to overtake and commandeer the car—he tied Danker to a tree, he tells his companion—Ellie and Peter stop at another motel. He wants to press on, as New York is only three hours away, but she insists they stay over—“What’s the hurry?”

While in their separate beds, she asks him if he has ever been in love. In another revealing monologue, Warne replies, “Sure I’ve thought about it. . . . You know, I saw an island in the Pacific once. . . . That’s where I’d like to take her.” Ellie leaves her bed, past the familiar blanket and kneels beside his bed. “Take me with you, Peter,” she begs. “Take me to your island. I want to do all those things you talked about. . . . I love you. Nothing else matters.” He insists she return to her bed.

While in their separate beds, she asks him if he has ever been in love. In another revealing monologue, Warne replies, “Sure I’ve thought about it. . . . You know, I saw an island in the Pacific once. . . . That’s where I’d like to take her.” Ellie leaves her bed, past the familiar blanket and kneels beside his bed. “Take me with you, Peter,” she begs. “Take me to your island. I want to do all those things you talked about. . . . I love you. Nothing else matters.” He insists she return to her bed.

After she has cried herself to sleep, Warne sneaks out, headed for New York to sell his story and announce to his boss (Charles C. Wilson) that he’s getting married. When she awakens, Ellie believes he has deserted her and returns to her father, who, relieved that she’s back, agrees to a second, formal wedding to Westley. But his daughter can’t fool him and she confesses she loves this reporter, but will nonetheless go through with the wedding.

When Peter arrives at the Andrews mansion, he asks only for the paltry $39.60 for his expenses, turning down the $10,000 reward. (Why would he be entitled to a reward? She returned of her own volition.) “Do you love my daughter?” Alexander Andrews asks him. Warne replies that only a crazy man would. Again and again Andrews presses against the repeated evasions, until Warne admits he does. “But don’t hold that against me,” he says, as he is leaving. “I’m a little screwy myself.”

When Peter arrives at the Andrews mansion, he asks only for the paltry $39.60 for his expenses, turning down the $10,000 reward. (Why would he be entitled to a reward? She returned of her own volition.) “Do you love my daughter?” Alexander Andrews asks him. Warne replies that only a crazy man would. Again and again Andrews presses against the repeated evasions, until Warne admits he does. “But don’t hold that against me,” he says, as he is leaving. “I’m a little screwy myself.”

As Andrews is walking his daughter down the aisle, he whispers that Warne refused the reward and tells her that her car is standing by for a quick get-away. Reaching the “I do” moment, she turns and dashes through the garden to find Warne. Andrews pays off Westley and Ellie and Peter are free to marry.

And the “it” in It Happened One Night? . . . In the final scene, Ellie and Peter, now married, have stopped at yet another motel for the night. The owner’s wife tells her husband that Warne asked for a rope and a blanket, and the husband says, why, he was sent to buy a toy trumpet. Outside, the lights from the windows of the cabin are lit when there’s the blast of a trumpet, the lights go out and a blanket drops to the floor. The Walls of Jericho have been, it appears, breached.

And the “it” in It Happened One Night? . . . In the final scene, Ellie and Peter, now married, have stopped at yet another motel for the night. The owner’s wife tells her husband that Warne asked for a rope and a blanket, and the husband says, why, he was sent to buy a toy trumpet. Outside, the lights from the windows of the cabin are lit when there’s the blast of a trumpet, the lights go out and a blanket drops to the floor. The Walls of Jericho have been, it appears, breached.